Margaret Fuller and Mary Wollstonecraft.doc

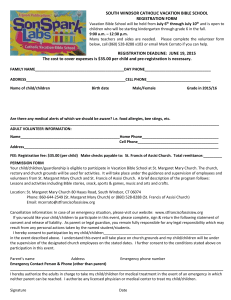

advertisement

Page 1/5 Margaret Fuller and Mary Wollstonecraft1 The dearth of new books just now gives us time to recur to less recent ones which we have hitherto noticed but slightly; and among these we choose the late edition of Margaret Fuller’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century, because we think it has been unduly thrust into the background by less comprehensive and candid productions on the same subject. Notwithstanding certain defects of taste and a sort of vague spiritualism and grandiloquence which belong to all but the very best American writers, the book is a valuable one: it has the enthusiasm of a noble and sympathetic nature, with the moderation and breadth and large allowance of a vigorous and cultivated understanding. There is no exaggerations of woman’s moral excellence or intellectual capabilities; no injudicious insistence on her fitness for this or that function hitherto engrossed by men; but a calm plea for the removal of unjust laws and artificial restrictions, so that the possibilities of her nature may have room for full development, a wisely stated demand to disencumber her of the parasitic forms That seem to keep her up, but drag her down— And leave her field to burgeon and to bloom From all within her, make herself her own To give or keep, to live and learn and be All that not harms distinctive womanhood.2 It is interesting to compare this essay of Margaret Fuller’s, published in its earliest form in 1843, with a work on the position of woman, written between sixty and seventy years ago—we mean Mary Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Woman. The latter work was not continued beyond the first volume; but so far as this carries the subject, the comparison, at least in relation to strong sense and loftiness of moral tone, is not at all disadvantageous to the woman of the last century. There is in some quarters a vague prejudice against the Rights of Woman as in some way or other a reprehensible book, but readers who go to it with this impression will be surprised to find it eminently serious, severely moral, and withal rather heavy—the true reason, perhaps, that no edition has been published since 1796, and that it is now rather scarce. There are several points of resemblance, as well as of striking difference, between the two books. A strong understanding is present in both; but Margaret Fuller’s mind was like some regions of her own American continent, where you are constantly stepping from the sunny “clearings― into the mysterious twilight of the tangled forest—she often passes in one breath from forcible reasoning to dreamy vagueness; moreover, her unusually varied culture gives her great command of illustration. Mary Wollstonecraft, on the other hand, is nothing if not rational; she has no erudition, and her grave pages are lit up by no ray of fancy. In both writers we discern, under the brave bearing of a strong and truthful nature, the beating of a loving woman’s heart, which teaches them not to undervalue the smallest offices of domestic care or kindliness. But Margaret Fuller, with all her passionate sensibility, is more of the literary woman, who would not have been satisfied without intellectual production; Mary Wollstonecraft, we 1 This essay, originally published in The Leader (1855), reviews two influential feminist works. Margaret Fuller (1810-1850), an American associated with the New England transcendentalist movement, was the author of Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1843; 1855). Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), the wife of William Godwin and mother of Mary Shelley, was bestknown for writing A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). 2 Tennyson, The Princess 7.253-58. Next Page Find Go to Page Thumbnail Index Image View Download a Copy Close