Exposure to Media Violence: The Effects of Witnessing Aggression 1

advertisement

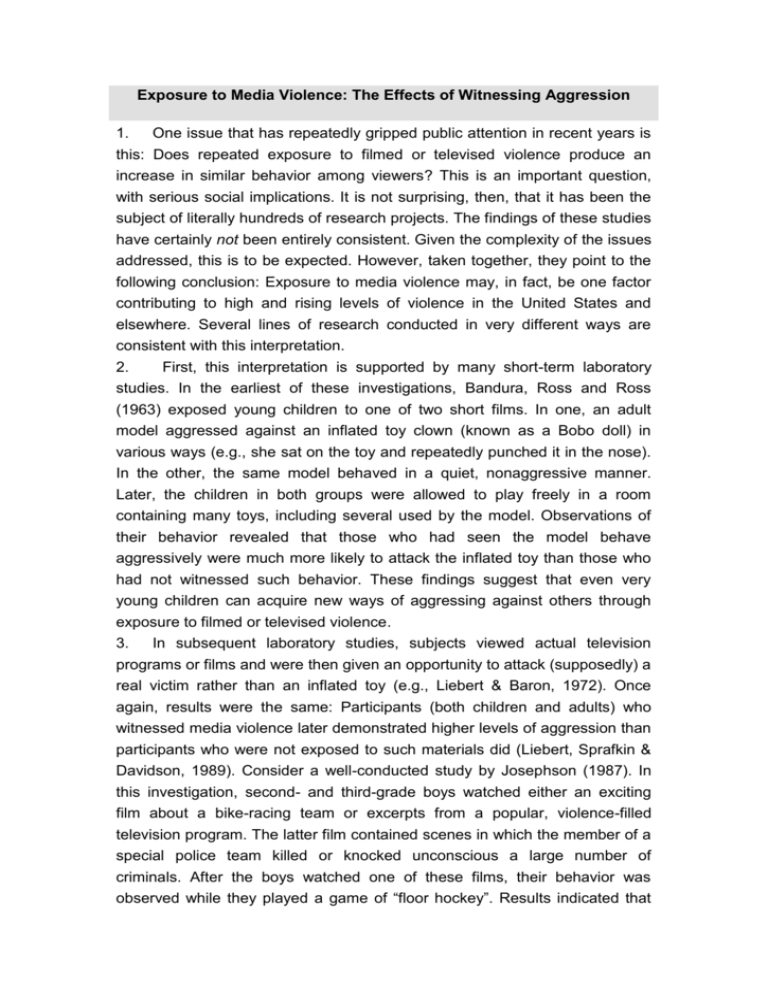

Exposure to Media Violence: The Effects of Witnessing Aggression 1. One issue that has repeatedly gripped public attention in recent years is this: Does repeated exposure to filmed or televised violence produce an increase in similar behavior among viewers? This is an important question, with serious social implications. It is not surprising, then, that it has been the subject of literally hundreds of research projects. The findings of these studies have certainly not been entirely consistent. Given the complexity of the issues addressed, this is to be expected. However, taken together, they point to the following conclusion: Exposure to media violence may, in fact, be one factor contributing to high and rising levels of violence in the United States and elsewhere. Several lines of research conducted in very different ways are consistent with this interpretation. 2. First, this interpretation is supported by many short-term laboratory studies. In the earliest of these investigations, Bandura, Ross and Ross (1963) exposed young children to one of two short films. In one, an adult model aggressed against an inflated toy clown (known as a Bobo doll) in various ways (e.g., she sat on the toy and repeatedly punched it in the nose). In the other, the same model behaved in a quiet, nonaggressive manner. Later, the children in both groups were allowed to play freely in a room containing many toys, including several used by the model. Observations of their behavior revealed that those who had seen the model behave aggressively were much more likely to attack the inflated toy than those who had not witnessed such behavior. These findings suggest that even very young children can acquire new ways of aggressing against others through exposure to filmed or televised violence. 3. In subsequent laboratory studies, subjects viewed actual television programs or films and were then given an opportunity to attack (supposedly) a real victim rather than an inflated toy (e.g., Liebert & Baron, 1972). Once again, results were the same: Participants (both children and adults) who witnessed media violence later demonstrated higher levels of aggression than participants who were not exposed to such materials did (Liebert, Sprafkin & Davidson, 1989). Consider a well-conducted study by Josephson (1987). In this investigation, second- and third-grade boys watched either an exciting film about a bike-racing team or excerpts from a popular, violence-filled television program. The latter film contained scenes in which the member of a special police team killed or knocked unconscious a large number of criminals. After the boys watched one of these films, their behavior was observed while they played a game of “floor hockey”. Results indicated that for boys who were rated by their teachers as being highly aggressive in the classroom, exposure to the violent programs had the expected effects. Those who watched these shows engaged in more acts of aggression during the hockey game (e.g., hitting others with their hockey stick, elbowing them, insulting them). Such findings were not obtained among groups of boys previously rated as nonaggressive – a finding suggesting that violence in the media is more likely to enhance aggression among persons who already have a strong tendency for such behavior than among those in whom this tendency is relatively weak. 4. Additional – and in some ways more convincing – evidence for the aggression-enhancing impact of media violence is provided by a second group of studies using different methods. In these long-term field investigations, different groups of subjects have been exposed to contrasting amounts of media violence, and their overt levels of aggression in natural situations were then observed (e.g., Leyens et al., 1975; Parke et al., 1977). Again, results indicate that youngsters exposed to violent programs or movies demonstrate higher levels of aggression than those exposed to nonviolent materials. 5. Third, other investigators have conducted long-term correlational studies in which the amount of media violence watched by individuals as children is statistically related to their rated levels of aggression several years – or even decades – later (e.g., Eron, 1982; Huesmann, 1982). Information on the amount of violence watched is based on subjects’ reports about the shows they watched plus violence ratings of these programs. Information on subjects’ subsequent levels of aggression is acquired from ratings of their behavior by classmates or teachers. The results of such investigations indicate that these two variables are indeed related: The more media violence individuals watch as children, the higher their rated levels of aggression as adults. Further, the strength of this relationship seems to increase with age, thus suggesting that the influence of media violence is cumulative over time. The more shows of this kind that individuals watch, the more likely they are to behave aggressively in a wide range of situations. 6. Finally, we should note that similar effects seem to occur as a result of playing aggressive video games, as well as from merely watching aggressive programs. (In a sense, such games provide players with an opportunity to participate in aggressive activities, or at least representations of them.) In one revealing study on this topic, Schutte and his colleagues (Schutte et al. 1988) had male and female children ages five to seven play one of two exciting video games. In the first, a violent game called “Karateka,” the character controlled by subjects hit or kicked various villains in order to destroy them. In the second, a nonviolent game called “Jungle Hunt,” the character swung from vine to vine while crossing a jungle. After playing one of these two games, children were observed, in pairs, in a special playroom. Results indicated that those who had played the aggressive game were more likely to hit both their playmate and an inflated doll than those who had played the nonviolent game. 7. Incidentally, additional findings indicate that even among adults, the greater individuals’ tendency to engage in “horse-play” (aggressive playfighting), the greater their tendency to engage in more harmful acts of aggression (Gergen, 1991). Thus, the relationship between aggressive play and actual aggression may be stronger than many persons suspect. 8. Again, we should add a note of caution. Not all findings have been consistent with the idea that exposure to media violence (or participation in aggressive video games) increases actual aggression (Freedman, 1984). Moreover, the evidence for relatively short-term effects of viewing violence are more firmly established by research than the potential long-term effects are. Still, existing evidence, when taken as a whole, seems to offer at least moderate support for the conclusion that exposure to media violence can contribute, along with many other factors, to the occurrence of aggressive behavior. Children see a lot of violence on TV and on films and videos. Do you AGREE or DISAGREE with the following statements? 1. Violence on TV and on films and videos can harm children. AGREE DISAGREE 2. Can children learn to be aggressive by watching violent acts on TV? AGREE DISAGREE 3. Viewing violence can make children scared of the world in which they live. AGREE DISAGREE 4. When TV violence is shown as funny, it doesn’t hurt children. AGREE DISAGREE 5. As long as there isn’t much blood and gore, TV violence isn’t a problem. AGREE DISAGREE 6. Violent cartoons are OK for children of all ages. AGREE DISAGREE 7. It’s good for children to watch TV news because it’s real life. AGREE DISAGREE 8. TV violence only hurts young children. AGREE DISAGREE 9. Parents can not / should not control the programs children watch. AGREE DISAGREE 10. The older the child, the less are they affected by viewing TV violence. AGREE DISAGREE Global Questions Skim the article and answer the following questions. 1. How does the writer answer the question in paragraph 1? ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ 2. The article can be divided to 3 parts. Fill in a description of each part: Paragraph(s) Para.1 Main idea Para. 2-7 Para. 8 3. In paragraphs 2-5 the writer reorts on three different groups of studies on viewing TV violence and its effects. Complete the following table with information on each group of studies reported: Group of studies Group 1 Type of studies Names of researchers Who were the subjects Group 2 Group 3 4. What is the relationship between paragraph 6 and the preceding paragraphs? Circle the correct answer: a. Par. 6 presents the final stage of the process described in pars. 2-5. b. Par. 6 adds another aspect of the issue investigated in pars. 2-5. c. a. Par. 6 compares and contrasts the ideas presented in pars. 2-5. d. a. Par. 6 summarizes the research presented in pars. 2-5. 5. Why does the writer suggest that we should be cautious about accepting the evidence presented in the article? a. ______________________________________________________________ b. ______________________________________________________________ Close Reading Questions 6a. List 2 differences between the study in para. 2 and the first study in para. 3. (i) ___________________________________________________________ (ii) ___________________________________________________________ b. What was similar about these studies? ________________________________________________________ 7. Fill in the blanks to show the difference between the findings of Liebert's studies and those of Josephson. Liebert's studies suggest that ____________________ can b affected by watching violence while Josephson's study suggests that _____________________ will be affected by watching violence. 8. Why does the author describe the evidence in paragraph 4 as "more convincing" than the previously cited evidence? ______________________________________________________________ 9. What do the findings of long-term co relational studies suggest? Fill in the blanks and circle the correct answer in the following sentence: If an individual watches ___________________________ as a child, he will become more ___________________________as an adult. Moreover, the correlation between these two variables dissipates / become stronger over years. 10. What factor indicates that the influence of media violence is cumulative over time? ______________________________________________________________ 11. What is the main idea of paragraph 6? Complete the following sentence: According to par. 6 ___________________________ can have similar effects as simply watching violent programs. 12. Complete the following sentence according to paragraph 7. Adults who refrain from aggressive play will be MORE / LESS likely to engage in harmful acts of aggression. This SUPPORTS / CONTRADICTS the idea that there is a STRONG/ WEAK relationship between play aggression and real aggression. Vocabulary Exercises Find synonyms for the following words in the text: Paragraph 1 1. unchanging, regular - _________________________ 2. help to cause; donate - ________________________ 3. in agreement with - ___________________________ (also para. 8) Paragraph 2 4. seeing and noticing - __________________________ 5. be present and see - __________________________ 6. get/obtain - _________________________________ Paragraph 3 7. later / following - _____________________________ 8. a part (of a book/film etc.) - _____________________ 9. estimate / assess (on a scale) - __________________ (also para. 5) 10. take part in something / be busy with something - _________________ 11. increase / add to; improve - _____________________ Paragraph 4 12. strong influence - _____________________________ 13. open / evident - ______________________________ Paragraph 5 14. something that can change according to conditions (in research) _____________ 15. increasing by additions - _________________________ 16. variety / extent - ________________________________ Paragraph 8 17. reasonable; medium - __________________________