English - Rural China Education Foundation

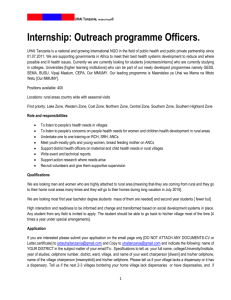

advertisement