A Review of People Development in the Australian Fishing Industry

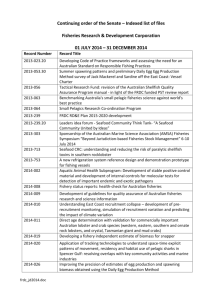

advertisement