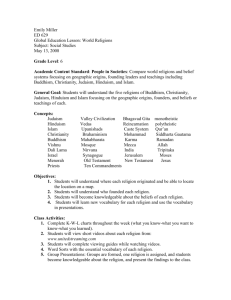

religion - Tolerance.it

advertisement