JAMAICAN ADVENTURES: SIMMEL, SUBJECTIVITY AND

advertisement

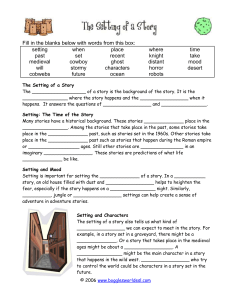

JAMAICAN ADVENTURES: SIMMEL, SUBJECTIVITY AND EXTRATERRITORIALITY IN THE CARIBBEAN. by HUON WARDLE As one of the key theorists of modernity, Simmel's writing remains strikingly underrepresented in recent anthropological theorizations of this subject. Drawing on Simmel's conception of adventure, this article considers the ways in which a sense of agency is created by working-class Jamaicans through their presentation of self in narrative. Adventure, as an aesthetic framing of individual experience, provides a temporal and spatial modality in which the individuated self can be reshaped into a protagonistic subjectivity for others. At the same time, the adventure presents a vehicle for an exploration of the meaning of freedom in a cosmopolitan field of social relations. The article examines the affinity that exists between the conditions for adventure, as Simmel outlines them, and the political-economic circumstances that govern Jamaican lives. Sidney Mintz's recent overview of the Caribbean region (1996) reminds us once again of the features that have, in the past, given this zone an anomalous status in anthropology. Together, slavery the plantation economy, colonialism and labour migration enforced a precocious and violent exposure to modernity for Caribbean peoples. [1] These factors also lent themselves to the region's vibrant social and cultural heterogeneity. Much attention has been paid by anthropologists both to this wider socialhistorical picture and to the varied modes of cultural expression that have emerged from it. In this article I take Caribbean individuals as my point of focus. [2] I ask how it is that Caribbeans come to construct and perceive themselves as agents in the social and cultural field of modernity and how this sense of agency is developed and reproduced. My analysis centres on the relationship between human movement and subjective imagining and I leave to one side here the varied claims that Caribbean people make to cultural rootedness and localized identity (Mintz & Price 1985). Instead, the article draws on one of the chief theorists of modernity, Georg Simmel (1965 [1911]), in order to place a particular aesthetic form, the adventurous episode, within the social-historical narrative that Mintz and others have laid out (cfTrouillot 1992). Adventure', I will argue, speaks to a recognizable organization of imaginative resources within a context shaped to a great degree by migration and social and cultural open-endedness. Most significantly, for the working-class Jamaicans discussed here, adventure provid es a concrete-metaphorical framework through which to explore the meaning of freedom. [3] Anthropologists have described extensively the structure of movement that is embedded in Caribbean life. In the 1960s and 1970s Philpott (1968; 1973) argued that we could hardly understand Caribbean society except through the networks of foreign migration that supported it: Caribbean social structure is not isomorphic with the Caribbean as a region. [4] In the 1980s, Drummond (1980), drawing on Brathwaite (1971) and Bickerton (1975), extended that notion to the sphere of culture. Caribbean culture, he argued, was best seen as a 'continuum', as open-ended rather than holistic: there was a need to investigate the ways individuals mediated, and made coherent, their manifold, often conflicting, cultural experiences (see also Drummond 1996: 76-88). While identification with locality is clearly evident in the Caribbean, ThomasHope (1978; 1995) has indicated how central movement is to Caribbean definitions of freedom. Despite the disillusionment that actual migration often brings, it remains a powerful cultural ideal. Extending Philpott's insights, Olwig (1993: 206) and Basch et al. (1994) have shown that Caribbeans find themselves caught up in, and 'deterritorialized' by, inter-generational social networks that overlap the boundaries, and ideologies of inclusivity, of nation states. Involvement in migrant networks affects both how actors understand social relations (Foner 1978; Olwig 1987) and also the strategies for economic viability that they deploy (Besson 1987a: 121; Griffith 1985; Segal 1997). [5] It is necessary then to comprehend Caribbean culture-building and patterns of movement within regional (Patterson 1986), global (Klak 1997) and historical frameworks (Richardson 1982; 1992). If social scientists have shown the open-ended nature of Caribbean society and culture, anthropologists such as Mintz (1960; 1971; 1996) and Wilson (1969; 1973; see also Besson 1993) have made clear how it is individuality or sociality-centred-in-personality that forms the cultural centre of gravity in this context. In Mintz's account, extensive individuation (due to the exigencies of plantation labour) and the formation of networks of dyadic relationships are a fundamental feature of Caribbean life. In Wilson's ethnography, it is through personal, usually oral, performance that the cultural relations of the wider colonial society are evoked and contested (see also Abrahams 1983; Burton 1997; Cooper 1993; Hebdige 1987). Hence, models which stress the individual and those which emphasize personality may give us two viewpoints on the same phenomenon. What this article contributes to these debates is an exploration of the kinds of cosmopolitan subjectivities that assert themselves within the continuum of Caribb ean social relations. Increasing economic informalization and frequent migration dictate that most working-class Jamaicans are engaged by necessity in broad webs of support, including rural and foreign-based kin, workmates, former and current bosses, political patrons, neighbours, sexual partners and friends from the bar or the street corner (Austin 1984; Comitas 1973). While they depend on these relations for a livelihood, people in east Kingston, my fieldwork area, also often portray them as claustrophobic, and describe as individuating the frequent fissures created in relationships by movement. In response, men and women emphasize the need for personal autonomy and the struggle for self-assertion that widespread social conflict, and an unstable political situation, demand. [6] Very often, this requirement for 'proving character' (Austin 1984: 231) takes the form of 'competitive dramatization' (Abrahams 1983: 143). In what follows, I explore the process of establishing selfhood within a cosmopolitan framework of social relations, concentrating in particular on one significant expressive modality through which the experience of individuation can be seen to instigate the assertion of personality. The crux of this article lies in the ways in which working-class Jamaicans shape their autobiographical experience into a form that corresponds strikingly with Simmel's delineation of adventure. I focus on a range of accounts where a kind of flight into another imaginative realm is thematically central or where, to use Simmel's (1965 [1911]: 246) term, a type of 'extraterritoriality' lies at the core. In doing so, I expose the relationship between adventure as a form of narrative and the political-economic situation in which Jamaicans find themselves. What these examples share is an interweaving of physical movement and imaginative migration. Revisiting Simmel's analysis, I investigate these narratives for what they tell us abou t the relation of self to others, time and space. Moving beyond Simmel's argument, I suggest that the importance of the adventure, as a form of self-expression, lies in its potential for shifting between real and metaphorical contexts of deterritorialization. The structure of adventure Simmel is the theorist of cosmopolitan sociality par excellence. For that reason it is surprising that his writing is so under-represented in current theoretical discussions of modernity, transnationalism and globalization (Frisby 1997). Throughout his work Simmel engages with the kinds of agency that people create in response to rapidly shifting fields of action and experience in the global metropolis (Simmel 1964; 1965 [1911]; 1997; see Levine 1991). A sense of agency is developed by way of a multiplicity of imaginative frameworks amongst which is the understanding of life as an 'adventure'. Simmel conceives of adventure as a genre that becomes significant, where a particular kind of relationship exists between subjects and the field of social relations in which they are active. Simmel is concerned with the relationship of adventure to everyday experience: adventures are episodes which exist at a distance from everyday life because they are removed from ordinary temporality and causality. Whereas everyday experience seems entangled in conflicting webs of causal entailment, adventures have definite beginnings and ends and their protagonists seem to act according to a unique mixture of fate and chance. One of the defining features of adventure is, then, this 'extraterritoriality with respect to the continuity of life' (Simmel 1965 [1911]: 246), the separation between normal life and adventure. As a type, the adventurer works within time constraints which differ from those of the everyday He is an 'extreme example of the ahistorical individual ... On the one hand, he is not determined by any past ... nor, on the other hand, does the future exist for him' (Simmel 1965 [1911]: 245). What is beyond the adventure is of little significance: the adventure contains its own self-sufficient and essential meanings. The 'extraterritoriality' of the adventure, outside the flow of life, parallels the displacement of the self into the adventure. The self of adventures is different from the everyday self and in certain ways more true to the protagonist's essential personality. In this respect, the characteristics of adventure give rise to a number of comparisons with roles similar to the adventurer's: the gambler, the artist, the religious ecstatic. The similarity with the gambler lies in the way contingency becomes part of the meaning of the event. The gambler insists on the magical patterns governing chance while, for the adventurer, the accident that gives rise to the adventure is forcibly coupled with the fateful necessity of events and the protagonist's role. On the other hand, comparison with the artist lies in the form of the adventure. Both the artist and the adventurer cut out and shape 'a piece of the endlessly continuous sequences of perceived experience ... giving it a self-sufficient form' (Simmel 1965 [1911]: 245). As with types of religious experience, in adventure there exists a sense that 'earthly' consciousness is only 'an isolated fragment' of an unknowable essence, a 'higher unity' (1965 [1911]: 247). There is also a dreamlike or visionary quality at work: 'the more "adventurous" an adventure, that is, the more it realizes its idea, the more "dreamlike" it becomes in our memory' (1965 [1911]: 244). Adventure then, in Simmel's formulation, shares something with other social roles and categories of aesthetic experience. [7] Nonetheless, as a category, it draws within itself specific configurations of imagination and self-knowledge. As we have seen, these characteristics include a metaphorical displacement of the self into the arena of adventure, the condensation of experience within an ahistorical and self-sufficient causal logic, and the feeling that in the adventure an essential self has been realized, even if only momentarily. Through these frameworks adventure sets the adventurer apart from others, as protagonist rather than simple experiencer. We should not, however, forget that adventure is also a species of narrative into which listeners can, potentially, transpose themselves imaginatively, and that fact is at the heart of the successful telling of an adventure. Perhaps it is also true that, even if it is never recounted, an adventure is always something shaped for the fascination of others. As Si mmel (1965 [1911]: 243) argues, the peculiarity of adventure is that it represents 'a foreign body in our existence which is somehow connected to the center'. In the next section, I focus on a dialogue from Jamaica, showing how the symbolic 'extraterritoriality' Simmel sees as the essence of adventure has taken on a very literal meaning within Caribbean imagining. 'The feeling of flying' Lee W. lives a precarious existence as a house painter and odd-job man in Kingston. He was born into a large extended family in the rural Blue Mountains in 1952. From the age of 14 he migrated widely around the island, from Annotto Bay in the north, to the violent impoverished ghettos of Central Village and Riverton City, witnessing the murderous political rivalries of the l980s. From there he arrived in east Kingston, already home to an older brother and sister. Throughout his life Lee has depended on an extensive network of family and friendship for economic survival. While many of his relatives have remained in the countryside, several have emigrated abroad, including a sister who lives in England. She visits periodically with her children, and the gifts and stories that she brings with her are eagerly anticipated. For economic reasons, but also for imaginative ones, it is a source of disappointment to Lee that he has never been able to emigrate and to 'see things over there in foreign' for himself. He oft en talks of his life in terms of its lost chances and indignities, but he also contests his situation with burlesque comedy and fantasy. In particular, Lee reacts by reshaping his own experience as a kind of adventure. On a Monday in August 1992, Lee and two other Kingstonian friends, Music-man and Marshy, were high in the hills of St Elizabeth in central Jamaica, hard at work on the foundation trench of a house they were helping to construct for Marshy's mother. The house was being built with the economic assistance of Jay, one of Marshy's daughters. Jay had lived in England most of her life but, in her twenties, she was now trying to re-establish contact with her Jamaican family, in particular her grandmother. There was much talk amongst the friends about Jay's visit and her new role in the family's affairs. With the group was Mas Robert, an elderly goatherd from across the valley, who, standing on the boundary wall, entertained the workers with stories from the Bible, tales of buried treasure and in citing pseudo-Roman epithets. Now it was time for lunch. In the heat of the afternoon, Lee sat on a stump and conversed excitedly with Robert on the 'spirit journey', their experiences of magical flight. Lee talked about his dreams of flight and how his father had a book that prophesied that these things would come true, but the book was lost when a member of Lee's family took it abroad. Robert had also experienced the 'feeling of flying': LEE: Enough time me vision say me are fly y'know, and my father tell me say 'boy one day it will come' ... ROBERT: Are you pass spirit you know ... LEE: Fly past the sea, an just go in, go in, straight to foreign y'know; and when me land me see a bright bundle are ... 'im something resemble gold ... ROBERT: Me say you see everything; spirit - spirit journey - fly you are fly man ... LEE: And my father read my planet man and later days coming up, me are go wealthy or wha' ... true man... ROBERT: you see ... LEE: Did have a book y'know: Ca a lady did borrow it - are my family y'know. It are miss up, an gone 'way a foreign and we no get it back ... [8] ROBERT: So life man ... that is the feeling of flying man; you pass spirit ... LEE: True man ... one day, one day ... It is possible to treat Lee's dream of flight both at an auto-biographical level and as a universal theme imminent in the human imagination. Likewise, we know that the image he calls on here, of flight to a foreign place and a bundle of gold at the journey's end, has particular salience for people in the Caribbean, where leaving to go to 'foreign' is so central to cultural and economic aspirations. McDaniel (1990; 1998) points to another dimension: she argues that, before emancipation, the image of magical flight made concrete the slave's dream of a return to Africa and continues to exist as a marker of Afro-centricity in Caribbean culture. Africa does not feature prominently in Lee's personal iconography, but that is not to say that the imaginative structure of salvation through displacement, initiated by the slave situation, is not reiterated in his dream narrative. There are good reasons why this might be so, as I explain in the next section. As for many of his Kingstonian friends, for Lee the concept of 'foreign' exists as a reality in terms of the friends and family who have visited and who live there. But it is also a concrete metaphor for freedom from current circumstances, personified in figures such as Lee's sister or Marshy's daughter Jay. I argue that we should see Lee's account as a universal theme, localized within the context of Caribbean history, but nonetheless made subjective through his particular social situation, which includes movement, and the aspiration for movement, as central referents. My aim then is to locate Lee's narrative of flight amongst a multiplicity of imaginative frameworks for 'extraterritoriality' in Caribbean life and to do so by drawing on the framework laid out by Simmel. In the case of Lee's description we may be talking less, to use Simmel's (1965 [1911]: 244) words, about the 'dreamlike' quality of adventure than about the 'adventurelike' quality of dream. [9] However, the structure of the account follows the form of Simmel's adventure in quite clear ways. Flight has a beginning and a rewarding end, arrival in 'foreign' and a bundle of gold, and the displacement, the metaphorical 'extraterritoriality' of adventure, is here literally present: in flying, Lee and Robert achieve a sensational (in both meanings of the word) escape from the everyday world. Significantly also, Lee contrasts the everyday facts of migration -- a member of his family leaving for 'foreign' -- with his personal imaginative flight: the disappointment caused by the lady taking the dream book away with her is woven into Lee's own aspirations for spiritual-real departure. Lee's story belongs to a type of Jamaican narrative which emphasizes the literalness of an 'extraterritoriality' that, for Simmel, is a metaphorical quality of adventures. In these Jamaican adventures, extraterritoriality, displacement into an alien framework of human and physical relations, is a concrete factor around which spiritual values are played out. The social relations involved in migration continuously re-emerge in the imaginative relations of adventure, and vice versa. In Lee's dream, adventure also provides the grounds for an exploration of the meaning of freedom and constraint, and it is this exploration that runs to the heart of the cosmopolitan and individualistic experience of modernity for working-class Jamaicans such as Lee. In the next section I give a wider historical and social context to this theme, re-examining its imaginative significance and showing how the adventure provides an arena for relocating the self in relation to others. Roaming Jamaicans: movement and freedom Mintz (1996) has argued that Caribbean people were modern even before Europeans. Transported into an alien geography emptied of indigenes, individuated by the socio-economics of colonialism, only through a complex reformulation could Caribbeans have recourse to the kinds of mythic narratives that would express the relationship of people to a landscape. For many, rapidly-changing work opportunities, in particular frequent migration, meant and mean a continuously moving spatial background for the comprehension and expression of self. There are, of course, Caribbean narratives that describe forms of rootedness in attachments to family and land (Dance 1985; Tanna 1984; see also Besson 1987a: 116-17). Nonetheless, I want to suggest that adventure has become a primary vehicle for the placing of self in relation to shifting social networks. The a historical nature of Simmel's adventurer has a strong affinity with the way individual experience is shaped by Caribbean sociality. This is certainly true in Jamaica, where , out of the historical necessity for movement, a whole imaginative reconfiguration has taken place. Thomas-Hope (1995: 161) shows how the realization of freedom after slave emancipation in the Caribbean necessitated a complete 'reorientation of self in place'. The freedom of ex-slaves to sell their labour was combined with a determination not to strike a bargain with former plantation owners. Two intermeshing strategies emerged. One was the establishment of free peasant farms in the island hinterland on the basis of pre-existing slave farming potential (Besson 1987b; 1992; Carnegie 1987; Mintz 1974). The other was external migration. Immediately after emancipation Jamaicans began to migrate, first to central America, particularly to Panama, then to the United States. So movement became part of the concrete enactment of freedom for former slaves, despite the fact that it also brought with it new exploitative relations. There rapidly developed a continuum of social relationships linking the rural interior, the migrant's 'country', with emigrant destinations in the cities or 'in foreign', a continuum re-estab lished over time through circular transmigration (Basch et al. 1994; Besson 1987a: 121; Olwig 1993: 206; Philpott 1968). As they moved, Jamaicans were forced to renegotiate their own place within shifting networks of relationships, and I suggest that adventure became a key narrative form in that renegotiation. One central moment in this linking of movement to a teleology of freedom is the 1920s and 1930s, when a popular Jamaican nationalism developed against the background of the collapse in the global economy and its devastating effects on the colonial periphery. Most importantly, the 1920s saw the emergence of a charismatic popular leader of international significance, Marcus Garvey. The theme of movement as a route to liberation was fundamental and recurrent in Garvey's political thinking. Like almost all the West Indian charismatic figures of the period -- including the radical preacher Alexander Bedward and the Rastafarian leader Leonard Howell [10] -- Garvey had experienced migration at first hand (Burton 1997: 123). It is striking how successfully he grasped a strand of Jamaican experience and imagination that had existed since emancipation and which continues to exist up to the present connecting, as we have seen, the fact of migration with the aspiration for freedom. In the early 1920s Garvey was involved in putting on a series of spectacular dramas in Kingston. One of these, shown to an extremely popular response in Edelweiss Park, was the epic 'Roaming Jamaicans'. From the bills for this play it becomes clear that Garvey's drama works with one of the key motifs of Jamaican imagining with great panache: A Grand Repetition of the Plays for Jamaicans A live human drama entitled Roaming Jamaicans Six acts, twenty one scenes written by the celebrated playwright Marcus Garvey author of The Coronation of an African King and Slavery from Hut to Mansion. ... This great play depicts the life of Jamaicans preparing to leave for America, Colon, Port Limon, Bocas del Toro, Nicaragua, Honduras and countries of South and Central America: and their manner of living abroad and their return. This will be a wonderful education for the people. Eighty characters in the play staged under the personal direction of the Hon. Marcus Garvey. See the life in Colon, see the things done in Port Limon and New York. Come and hear the conversation between Florence Green and Henry Williams, two typical characters in Colon. Come and see West Indians arrested in New York for drinking a bottle of J Wray and Nephew's Rum, Come and see a Gardener Boy from Jamaica making love to his mistress in America. You can't miss this drama that has so much information for you. Curtain rises at 8 sharp. This play was a wonderful success last Monday and Tuesday nights. A repetition is asked for. General Admission one shilling (Hamilton 1987: 24) As in epic films of the period, Garvey captures the essence of an experience through a montage of multiple, interwoven, scenes. Particularly striking, though, is the contemporaneous quality of this interweaving: the spectacle is built up of events happening in widely disparate places at the same time, and it is left to the viewer to build a context out of this montage. The condensation of the experience of these everyman adventurers -- Florence Green, Henry 'Williams -- into a sequence of triumphant episodes in dispersed locations finds an immediate point of affinity with Jamaican modes of self-representation. The success of the play depended not only on Jamaicans recognizing themselves as protagonists in the drama of everyday migration, but also on their gaining a sense of the common adventure in which they were part and of the way in which they played a distinctive role on the global stage. Garvey's play gives us another perspective on the wider context of imaginative expressions like Lee's dream of flight, demonstrating in particular how such accounts are tied, as Thomas-Hope shows, into an attempt to understand and to achieve freedom. Perhaps not surprisingly, given his capacity to capture the concrete experience of displacement within the form of adventure, Garvey, like Bedward before him, was credited by many Caribbeans with the ability to fly (McDaniel 1990: 37). A clear dialectic exists between concrete and imaginative dimensions of displacement and, as I have explained, these give shape to an ideology of freedom through the modality of adventure. Adventure reshapes the spatial and temporal experience of migration within its imaginative parameters, repositioning the Caribbean individual as an agent in relation to these processes. In the next section I return to the level of individual experience and imagination, examining how religious sensibility, in play with the experience of individuation and the contingencies of migration, provides a fertile ground for the adventure form. Displacement, gnosis and self-knowledge A characteristic feature of the Caribbean is its vast number of churches and the rivalry that exists between their leaders (Besson 1993: 24-5). The other side of that coin is the personalist and gnostic approach that ordinary people very often take to religion, whereby formalized ritual is far less valued than personal religious vision. An extraordinary example of that is the autobiography of the charismatic Grenadian faith healer Norman Paul (in Smith 1963). Paul provides the classic instance of the Caribbean whose highly idiographic religious understanding -- based in a series of revelatory events in Grenada, the Dutch Antilles and Trinidad -- is deeply intertwined with his migrant experience. The account ranges across a working life in those islands during the political and economic chaos of the interwar years, a failed marriage, his experience of physical and spiritual affliction and his final success as a healer. The story mirrors some of the grand-scale themes presented in Garvey's play, and there are e choes of Lee's vision of flight, as when Paul describes the dreams that led up to his migration to Aruba: One night I dreamt I was walking the road, and a large amount of bees flew around me, and stang me through my ears, my nose and so on. I was so frightened. The next day, relating it to a friend of mine, he told me it was prosperity. And another time, before 1927, I dreamt I was walking on the Hampstead estate and I got to a plum-tree that was blacked on the leaves and everything; and I told him again, and he said 'that is prosperity coming and not long'. And my brother came in 1927 from Maracaibo and he took me to Aruba. And while I was travelling to Aruba, several nights on the boat I would dream of a large amount of shell corn, and I told him, he said, well, I would be very prosperous where I was going (Smith 1963: 53). The experience of migration is an individuating one in which the capacity to take on any task and to rely on oneself become paramount virtues: that is the context in which Paul's account constantly reformulates itself The sense in which the struggle with chance is a permanent feature of the migrant's experience is made clear in Paul's description of another trip ten years later: I left here [Grenada] with one pants during that strike in Trinidad in 1937. When everybody landed in Trinidad they were sent back. I consulted the captain of the vessel, he managed to get me on one of the buses. I left here, one pants, one jacket, one merino, and more than that one shilling in my pocket after I bought my passage. One shilling. The bus charge a shilling from Port-of-Spain to San Fernando, and I paid a shilling for a drop in San Fernando that morning. As soon as I drop I met somebody I knew in Carriacou, and he took me home. And when I related what happened, well, they helped me out for the week and I went to find a job (Smith 1963: 66). Like Lee's dream of flight, fate in the form of movement is pitted against adverse luck, and the insistence of destiny reflects and reverses the imponder-ability of migrant life. And we have seen that the individuation that migrancy brings about does not create the grounds for non-belief: Paul's account suggests the reverse, that a strong sense of a higher meaning to personal experience grows out of the encounter with extreme imponderability. Paul is able to reformulate the contingencies of movement as religious-symbolic elements in an encompassing personal narrative woven through a sequence of adventures. Once again, the interpenetration of migration and its imaginative reformulation around the central image of 'extraterritoriality' provides a groundwork for 'proving character' (Austin 1984: 231). What Paul's account adds, though, is the clear sense in which the elements of his personal narrative are reshaped from chance connexions within a cosmopolitan field of social relations and communication. From individuation to personality Norman Paul's account shows, in detail, how a gnostic religious sense is brought to bear on the experiences of displacement and contingency. Below I present three excerpts from a conversation between myself and an artist, Leonard Daley. Daley, like Paul, is a master of the autobiographical genre. His style is highly personal, creative, idiosyncratic, but the mode of exposition -- its probings, overturnings and rhetorical reversals -- are common to Caribbean forms of expression, as is the element of 'competitive dramatization' (Abrahams 1983: 231). [11] The characteristic of Daley's discourse is knowledge of self poised against the world. Central to adventure, as we have seen, is the triumph over the chance qualities of personal adversity and, thereby, the increased sense of an underlying spiritual teleology at work. It is in the realm of adventure that the individuated self gives onto a protagonistic personality. Like my friend Lee, who was present on this occasion, Daley has lived in many parts of the island and his stories take movement as a given: Lee and Daley immediately established a rapport discussing their network of shared acquaintances. In the conversation recorded here Daley draws on a series of experiences from his everyday life -- arriving in a new location, a conversation at a party -- shaping each one into an epiphanic event which he then trawls for revelatory meaning. LEONARD DALEY: When I came in this area and mark on my shirt back from a man [12] - I don't read, I never been to a school for reading, no, I never write a letter from me born neither do I read one (uses past tense then corrects himself), or read one I should say. Now look, I ask a guy over there-so if he can read and he say 'yeh'. I say 'mark on this shirt back "I Am Sorrow"'. -you know anybody like sorrow? you know anybody like sorrow? LEE: Uhhn (negatively). LEONARD DALEY: Look what is sorrow man, eh! you don't know anybody like it, but where joy come from?! Question ask again: where you get joy from? Without sorrow where you get any damn joy from? 'I Am Sorrow': The words form a locus around which revolves Daley's arrival in a new place, his anonymity his illiteracy and the role of an unknown man in writing out an identity for him on the back of his shirt. The phrase has the weight of sublime finality about it, but it also becomes the vehicle for a further exploration of Manichaean forces, Sorrow and Joy. Here we have an event, an episode, an epiphany, an adventure which fulfils many of the criteria discussed by Simmel: it has its own internal logic, its own constraints of time and place; it displaces the individual into a new field of relationships which become the locus of a process of self-understanding, self-actualization. From within these parameters the individual emerges as the agent of his own destiny. Moreover, in Daley's account the religious and aesthetic qualities that Simmel links with adventure are trenchantly mixed. Further, the gnostic elements that are a broad feature of this kind of discourse are worked through by Daley extremely deeply, even by Jamaican standards. In the second of these excerpts, he uncovers a new persona; this time not as 'Sorrow' but as a 'Professional Cleaner of Filth', a role which has a distinctly Socratic ring to it. LD: I am just a servant, anyway you see, of people. The other day I was at a party in New Kingston and a brother come and ask me what's my profession. I say, 'I'm a Professional Filth Cleaner'. And he laughed and laughed and laughed. But if you are not a professional man you are fuck-up-outthe-road - you smell frowzy. I'm a Professional Cleaner of Filth and I clean all my children too. Its the same with my dirt. What's the shame about that?... I create nastiness, you know. But you must create ... because when I spit it's nasty to somebody. If my eyes stay a way, mouth stay a way it nasty to somebody, nose running it nasty to somebody, and it's really nasty to me that see it. (Laughter). LD: So I can't ... I'm just nasty - anything you call me - what you could call me? Yesterday I put money upon a painting - upon a crow ... [13]. HW: John Crow [vulture]? LD: That bird -John Crow. Its a symbol of me - it cleans place. HW: True. LD: Cleans Place. It don't dirty place. It don't trouble people. HW: True. LD: No ... That bird. But they call it 'Nasty'. Again, Daley uses an autobiographical episode to explore a series of paradoxes and mysteries concerning the relation of self to the world: immersion in filth is also immersion in truth, the revelation of dirt is also the revelation of hope. New Kingston is amongst the newest and richest districts in the city. Daley is one of the 'intuitive' painters whose work is shown nationally, and this gives him unusual access to the world of the Jamaican elites. Though he does not specify, it is almost certain that he is here describing a private view of paintings and that his interlocutor belongs to the educated middle class. In that context, Daley's projection of himself as a 'Professional Filth Cleaner' is razor sharp, though his addressee seems unaware of it. Daley's identification with the misunderstood vulture displaces him from others, those who call the bird nasty but also gives him a particular vantage point on everyday experience. The third excerpt comes directly after another autobiographical episode. In it, Daley has described how a girlfriend had protected her house against robbers with a series of locked grills: but he tells her that such a procedure is useless since it is 'the one you love that is the thief'. Here he changes tack again, reinforcing the idea of an almost monad-like self poised against the world. LD: So you can't get away from judgement. I bring it ... to get justice. You know I don't want a man to know me by my name. HW: hmm. LD: Away from ... The name that you give brother D - my name is Leonard G Daley (G stand for George) - its not my name; its not my name; its what my parents request. LEE: Truth - so you just work off of that. LD: Eeh - work off of that. Now they go and they register the baby. The register not right. Not Right. I ask a question: 'out of the baby and the birth certificate which one is before the other?' LEE: The baby? LD: Then how the birth certificate for be right? Hhm. No one in this world knows who he is. Its impossible for you to know who you are... LEE: Just are guess ... In this account, and it has been intimated in the earlier excerpts, the self exists as an essence quite independent of accepted contexts, other people's actions, even one's own beliefs. Knowledge of this self involves progress through a series of condensed, in a sense timeless, revelatory experiences. The feeling that an aporea exists between the essential, eternal self and the often contradictory statuses ascribed to the individual in the everyday takes us back to Simmel once again. The real self can never be known in the everyday: it is the adventure or the epiphany that reveals aspects of it, if only in a mysterious and Delphic way. But, of course, besides giving him a unique vantage point on everyday reality, Daley's adventures provide him with a particular personality with regard to his audience: this is because, paradoxically, out of the experience of placelessness and identity-lessness, the adventure gives him a space and a role, the space of adventure and the role of protagonist. Conclusion 'When we have no home but merely temporary asylum on earth', suggests Simmel, 'this is only a variant of the general feeling that life is an adventure' (1965 [1911]: 248). I do not claim that the adventure as a mode of cultural expression is unique to Jamaica. Similarly, I do not argue that adventure excludes all other narrative genres: there are other stories in Jamaican life that speak of longstanding attachments; to territory, for instance (Besson 1987a: 116-17). I have, however, suggested that adventure, as Simmel outlines it, has a strong affinity with the forces shaping the lives of individual Jamaicans and that it is a useful concept in the process of understanding how these cosmopolitans reshape a self around the real and metaphorical ground of displacement. Out of the array of aesthetic forms through which individuals organize their experience of the world, adventure comes to the fore for understandable reasons. Philpott (1968; 1973) has shown us that Caribbean social structure is founded, politically and economically, in the dispersing and reaggregating forces of migration. Drummond (1980) indicates the open-ended nature of a Caribbean cultural continuum made up of many overlapping and often contradictory discourses which actors work through, mediate and make coherent. In different ways, Lewis (1968), Mintz (1971; 1996) and Wilson (1969; 1973) have demonstrated the significance of individuality or personality as the social and cultural centre of gravity in response to pre- and postemancipation colonial power. Within these theoretical parameters I have given an account of the place of adventure in the self-presentation of the Jamaicans that I have worked with. Exceptionally violent, with an ineffectual political apparatus prone to authoritarianism, a faltering economy and high migration rates, Jamaica exaggerates some key facets of Caribbean social experience (Austin-Broos 1996; Edie 1990; Harrison 1997). In a context that is highly individuating, the adventure plays a key role in the process which Thomas-Hope (1995: 161) describes as 'reorientation of self in place'. The search for freedom through migration which Thomas-Hope points to at the macroscopic level is pivotal also in individuals' imaginings of their self's relation to others. Displacement into adventure not only enables the emergence of a kind of protagonistic personality it also creates a framework through which the individual can explore and, perhaps, make real the meaning of freedom. The ahistorical nature of adventure matches the momentary character of people's connexions with each other: the imaginative displacement central to adventure mirrors a practical experience of movement. But the form of t he adventure works to frame the protagonist's relationship to these qualities within a higher unity, a fateful collusion between luck and chance, and is unbounded in its potential for creative elaboration. Pursuing arguments made by Bruner (1996), Carrithers has recently pointed to the ways that people 'confabulate society using stories' (1995: 275). Carrithers also suggests that 'there can be no minimal definition of what constitutes a narrative' (1995: 267-8). I think that, as Simmel argues, adventure contains a consistently recognizable mix of form and content, even if elements of that mix are shared with other aesthetic kinds. We can see Simmel's adventure and these Jamaican dreams and stories as partaking of a particular Judaeo-Christian worldview. We can also understand accounts like Lee's dream of flight in Eliadian terms as reflecting more universal cognitive patterns (Eliade 1970), or as 'liminoid' experiences producing particular results for the subject (Turner 1974). My purpose here has been to examine the way a specific narrative modality has been put to work in a given politicaleconomic context. Once again, Jamaicans are not unique in having adventures: it is the way in which adventure comes to the fore in relation to, for instance, myth, artistic appreciation, or ritual, that is significant. Myth may contain adventure-like qualities, but its emphasis is on the validating role of the past rather than ahistorical validation via the immediate. Similarly, disinterested artistic appreciation may have a totalizing role for the individual, but the kind of sensibility constructed out of the relationship between self and art object contrasts radically with the protagonism of adventure. In ritual, formalization far outweighs contingency. All of these forms merge into each other at particular points on the aesthetic matrix; each of them provides the potential, reflexive grounds from which can emerge certain kinds of subjectivity -- ritualistic, connoisseurial, protagonistic; one or other of these forms may predominate within particular contexts of experience. The heightened individuation experienced by many J amaicans is a fertile ground for a heightened sense of self-as-protagonist, self-as-adventurer. There is a forceful cohesion between the deterritoriality engendered in the lives of Caribbean people and the extraterritoriality reworked imaginatively in their self-expression. And the life construed in terms of adventure reproduces particular understandings of self in place and time, self in relation to others. Importantly, the success of an adventure as a narrative lies in the capacity of listeners to place themselves within its framework. Paradoxically, the greater the displacement involved in the adventure, the more the listener wishes to enter into it as a vicarious protagonist. The adventure thereby creates social relations by providing the temporal and spatial parameters for imaginative relations. That is one significant reason why the adventure works so well as a mode of expression in a dispersed, cosmopolitan milieu: the ahistorical, immediate logic of adventure is available even where a shared landscape and shared meanings may not be. [14] Towards the end of his essay, Simmel (1965 [1911]: 257) reflects that 'none of us could live one day if we did not treat that which is incalculable as calculable, if we did not entrust our strength with what it still cannot achieve by itself but only by its enigmatic co-operation with the powers of fate'. By that token, the more predictable the context of our lives, the smaller the role that adventure has to play. Ordinary Jamaicans still live amidst some of the most unpredictable and harsh social conditions in the world. The capacity of adventure to bring together 'the fragmentary materials given us from the outside and the consistent meaning of life developed from within' (Simmel 1965 [1911]: 247) assures it a central place in Jamaican selfexpression. NOTES I thank especially Paloma Gay y Blasco, David Riches, Joanna Overing, Nigel Rapport, Keith Hart and two unnamed reviewers for their helpful comments. (1.) The arguments for the Caribbean as an exemplary case of modernity extend a long way back in Caribbean social theory, particularly to the work of C.L.R. James (e.g. 1963). James's MarxistHegelian synthesis has had a widespread influence on later commentators (e.g. Miller 1994). (2.) The emphasis here is on subjective experience. For a discussion of the ways in which individuality allows for communal solidarity see Wardle (1995). (3.) The two detailed accounts included here come from Jamaican men. I chose to work from tape transcripts in order to focus on the qualities of spoken utterance, and the dialogues with Lee and Leonard Daley provided the two most coherent and trenchant examples captured on tape. Jamaican women also migrate and I have collected a range of evidence to show that they also draw on the adventure form and exploit it to the full. The fact that the materials presented come from men should not then be taken as representative of a gender imbalance in Jamaican discourse itself I have explored women's experiences and narratives of migration elsewhere (Wardle 1998). (4.) Since the 1840s Jamaica has been at the forefront of these migration processes. In the early 1980s the island had the highest legal immigration to the US of any state per capita (Grasmuck & Pessar 1991: 22). During the 1980s, 10 per cent. of the island's population emigrated to the US and Canada (De Souza 1997: 230), so it is unlikely that any working-class Jamaican individual or extended family is unaffected by migration. (5.) While the Jamaican economy has declined since the 1970s (Harrison 1997), migration, with its potential for creating and reproducing personalized economic linkages, has been a pre-eminent force in sustaining the informal sector. (6.) The struggle for limited resources combined with ineffectual but nonetheless repressive political control has resulted in Jamaica, specifically Kingston, becoming one of the world's most violent civil societies (Calathes 1990; Lacey 1977; World Bank 1997). (7.) Compare Simmel's adventure with Dewey's account of 'an experience' (1934; see also Wardle 1995). (8.) We had a book but a lady borrowed it - a member of my family. The book was lost; taken abroad, and we never gut it back'. Lee emphasizes the fact that it was all the more disappointing to lose the book because it was a member of his family that took it away. One could expect better from one's own family. (9.) In themselves dreams have a major significance in Caribbean life as a revelation of personal potential. Jamaicans continuously assess their day-to-day life chances against a reading of their dreams, especially in the choices involved in betting games. However, as will become apparent, my concern here is not with dreams as such but with the way certain dreams are presented as adventure. I have heard several accounts of magical flight from Jamaicans. What comes across most strongly is that this is a personal gift or capacity: certain activities, such as murder, are sometimes explained by the individual having been 'haunted' by a ghost; that is not the case with magical flight. (10.) Though there is limited space to discuss it here, the influence of Garvey's 'Back to Africa' philosophy in the formation of Rastafarian beliefs in the 1920s and 1930s is well documented (AustinBroos 1997: 192-3; Barrett 1977; Chevannes 1994). (11.) These kinds of reversals of meaning, particularly regarding moral implication, and personified in the mythic activities of Anansi the Trickster, are an omnipresent motif in Caribbean discourse (e.g. Burton 1997; Manning 1973). Austin-Broos (1997: 141) makes an important argument for the role of 'the trick' as a pivotal idiom in Jamaican religious conversion. (12.) 'When I came to this area a man marked on the back of my shirt ...' (13.) 'I spent money (on materials) for a painting of a vulture'. (14.) As one reader of an earlier version of this article points out, a key location in which adventure comes to the fore currently is in dance-hall music: songs typically describe a self poised heroically against an unrelenting world, and there is, once again, frequent reference to travel to New York, London or Toronto as a self-validating framework (Cooper 1993; Stolzoff 1997) REFERENCES Abrahams, R.D. 1983. The man-of-words in the West Indies: performance and the emergence of Creole culture. London: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. Austin, D. 1984. Urban life in Kingston, Jamaica: the culture and class ideology of two neighbourhoods. London: Gordon & Breach. Austin-Broos, D. 1996. Politics and The Redeemer: state and religion as ways of being in Jamaica. Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 70, 1-32. ----- 1997. Jamaica genesis: religion and the politics of moral orders. Chicago: Univ. Press. Barrett, L. 1977. The Rastafarians: the Dreadlocks of Jamaica. London: Heinemann Educational. Basch, L., N.G. Schiller & C.S. Blanc 1994. Nations unbound: transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments, and deterritorialized identities. London: Gordon & Breach. Besson, J. 1987a. Family land as a model for Martha Brae's new history: culture building in an AfroCaribbean Village. In Afro-Caribbean villages in historical perspective (ed.) C.V. Carnegie. Kingston: Afro-Caribbean Institute of Jamaica. ----- 1987b. A paradox in Caribbean attitudes to land. In Land and development in the Caribbean (eds) J. Besson & J.H. Momsen. London: Macmillan. ----- 1992. Freedom and community: the British West Indies. In The meaning of freedom: economy, politics and culture after slavery (eds) F. McGlynn & S. Drescher. Pittsburgh: Univ. Press. ----- 1993. Reputation and respectability reconsidered: a new perspective on Caribbean women. In Women and change in the Caribbean (ed.) J. H. Momsen. London: James Currie. Bickerton, D. 1975. Dynamics of a Creole system. Cambridge: Univ. Press. Brathwaite, E.K. 1971. The development of the Creole society in Jamaica, 1770-1820. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Bruner, J.S. 1996. The culture of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press. Burton, R.D.E. 1997. Afro-Creole: power opposition and play in the Caribbean. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press. Calathes, W. 1990. Jamaican firearm legislation: crime control, politicization, and social control in a developing nation. Int. J. Social. Law 18, 259-85. Carnegie, C. (ed.) 1987. Afro-Caribbean villages in historical perspective. Kingston: Afro-Caribbean Institute of Jamaica. Carrithers, M. 1995. Stories in the social and mental life of people. In Social intelligence and interaction: expressions and implications of the social bias in human intelligence (ed.) EN. Goody Cambridge: Univ. Press. Chevannes, B. 1994. Rastafari: roots and ideology. Syracuse, NY: Univ. Press. Comitas, L. 1973. Occupational multiplicity in rural Jamaica. In Work and family life: West Indian perspectives (eds) L. Comitas & D. Lowenthal. New York: Anchor Books Cooper, C. 1993, Noises in the blood: orality, gender and the 'vulgar body' of Jamaican popular culture. London: Macmillan. Dance, D. 1985. Folklore from contemporary Jamaicans. Knoxville: Univ. of Tennessee Press. De Souza, R-M. 1997. The spell of the Cascadura: West Indian return migration. In Globalization and neoliberalism: the Caribbean context (ed.) T. Klak. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield. Dewey, J. 1934. Art as experience. London: G.P. Putnam & Sons. Drummond, L. 1980. The cultural continuum: a theory of intersystems. Man (N.S.) 15, 352-74. ----- 1996. American dreamtime: a cultural analysis of popular movies and their implications for a science of humanity. London: Littlefield Adam. Edie, C. 1990. Democracy by default: dependency and clientalism in Jamaica. Boulder: Lynne Riener. Eliade, M. 1970. Myths, dreams and mysteries: the encounter between contemporary faiths and archaic realities. London: Collins. Foner, N. l978.Jamaica farewell: Jamaican migrants in London. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Frisby, D. 1997. Introduction to the texts. In Simmel on culture: selected writings (eds) D. Frisby & M. Featherstone. London: Sage. Grasmuck, S. & P. Pessar 1991. Between two islands: Dominican international migration. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. Griffith, D. 1985. Women, reproduction and remittances. Am. Ethnol. 12, 676-90. Hamilton, B. 1987. Marcus Garvey: cultural activist. Jamaica J. 20, 21-32, Harrison, F.V. 1997. The gendered politics and violence of structural adjustment. In Situated lives: gender and culture in everyday life (eds) L. Lamphere, H. Ragone & P. Zavella. London: Routledge. Hebdige, D. 1987. Cut 'n' mix: culture, identity and Caribbean music. London: Routledge. James, C.L.R. 1963. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo revolution. New York: Vintage Books. Klak, T. 1997. Thirteen theses on globalization and neoliberalism. In Globalization and neoliberalism: the Caribbean context (ed.) T. Klak. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield. Lacey T. 1977. Violence and politics in Jamaica: 1960-1970. Manchester: Univ. Press. Levine, D.N. 1991. Introduction. In G. Simmel, on individuality and social forms (ed.) D.N. Levine. Chicago: Univ. Press. Lewis, G.K 1968. The growth of the modern West Indies. London: MacGibbon & Kee. Manning, F. 1973. Black clubs in Bermuda: the ethnography of a play world. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press. McDaniel, L. 1990. The flying Africans: extent and strength of the myth in the Americas. Nieuwe WestIudische Gids 64, 28-40. ----- 1998. The big drum ritual of Carriacou: praisesongs in rememory of flight. Gainsville: Univ. Press of Florida. Miller, D. 1994. Modernity, an ethnographic approach. Oxford: Berg. Mintz, S. 1960. Worker in the cane: a Puerto Rican life history. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. ----- 1971. The Caribbean as a socio-cultural area. In Peoples and cultures of the Caribbean: an anthropological reader (ed.) M.M. Horowitz. Garden City, NY: The Natural History Press. ----- 1974. Caribbean transformations. Chicago: Aldine. ----- 1996. Enduring substances, trying theories: the Caribbean region as oikumene. J. Roy anthrop. Inst. 2, 289-313. Mintz, S. & S. Price (eds) 1985. Caribbean contours. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. Olwig, K. F. 1987. Children's attitudes to the island community: the aftermath of out-migration on Nevis. In Laud and development in the Caribbean (eds) J. Besson & J.H. Momsen. London: Macmillan. ----- 1993. Global culture, island identity: continuity and change in the Afro-Caribbean community of Nevis. Philadelphia: Harwood. Patterson, O. 1986. The emerging West Atlantic system. In Population in an interacting world (ed.) W. Alonso. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press. Philpott, S.B. 1968. Remittance obligations, social networks and choice among Monserratian migrants in Britain. Man (N.S.) 3, 465-75. ----- 1973. West Indian migration: the Monserrat case. London: Athlone. Richardson, B. 1982. Caribbean migration 1838-1995. In The modern Caribbean (eds) F. Knight & C. Palmer. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press. ----- 1992. The Caribbean in the world economy, 1492-1992. Cambridge: Univ. Press. Segal, A. 1997. The political economy of migration. In Globalization and neoliberalism: the Caribbean context (ed.) T. Klak. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield. Simmel, G. 1964. The sociology of Georg Simmel (ed.) K. Wolff. New York: The Free Press. ----- 1965 (1911). The adventure. In Georg Simmel: essays on sociology, philosophy and aesthetics (ed.) K. Wolff. New York: Harper Torchbooks. ----- 1997. Simmel on culture: selected writings (eds) D. Frisby & M. Featherstone. London: Sage. Smith, M.G. 1963. Dark Puritan. Kingston: Department of Extra-Mural Studies, Univ. of the West Indies. Stolzoff, N.C. 1997. Wake the town and tell the people: dancehall culture in Jamaica. Thesis, University of California. Tanna, L. 1984.Jamaican folk tales and oral histories. Kingston: Institute of Jamaica Publications. Thomas-Hope, E.M. 1978. The establishment of a migration tradition: British West Indian movements to the Hispanic Caribbean in the century after emancipation. In Caribbean social relations (ed.) C.G. Clarke. Liverpool: Univ. Press. ----- 1995. Island systems and the paradox of freedom: migration in the post-emancipation Leeward Islands. In Small islands, large questions (ed.) K.F. Olwig. Ilford: Frank Cass. Trouillot, M-R. 1992. The Caribbean region: an open frontier in anthropological theory. Ann. Rev. Anthrop. 21, 19-42. Turner, V. 1974. Liminal to liminoid, in play, flow, and ritual: an essay in comparative symbology. In The anthropological study of human play (ed.) E. Norbeck. Houston: Rice Univ. Press. Wardle, H. 1995. Kingston, Kant and common sense. Camb. Anthrop. 18, 40-55. ----- 1998. Strangers in the continuum: Jamaicans and anthropologists as cosmopolitans. Presented at the Biennial Conference of the European Association of Social Anthropologists, Frankfurt, 4-7 September. Wilson, P.J. 1969. Reputation and respectability: a suggestion for Caribbean ethnology. Man (N.S.) 4, 71-84. ----- 1973. Crab antics: the social anthropology of English-speaking Negro societies of the Caribbean. London: Macmillan. World Bank 1997. Violence and urban poverty in Jamaica: breaking the cycle. Washington, DC: World Bank. Aventures de Jamaique: Simmel, la subjectivite et l'extra-territorialite dans les Caraibes Resume L'oeuvre de Simmel, bien qu'il soit l'un des principaux theoriciens de la modernite, continue etre singulierement mal representee dans les debats theoriques sur le sujet en anthropologie. S'inspirant de la conception de l'aventure de Simmel, cet article considere les moyens par lesquels les Jamaiquains de classe ouvriere creent une impression d'action lorsqu'ils se representent eux-memes dans leurs recits. L'aventure, en tant que cadre esthetique de l'experience individuelle, offre une modalite temporelle et spatiale dans laquelle le sujet individualise peut se remodeler dans une subjectivite de protagoniste envers les autres. En meme temps, l'aventure presente un vehicule pour explorer la signification de la liberte dans un champ cosmopolite de relations sociales. Cet article examine l'affinite qui existe entre les conditions de l'aventure, telles que Simmel les esquisse, et les circonstances politiques et economiques qui gouvernent la vie des Jamaiquains. Dept of Social Anthropology, Queen's University, Belfast, NI BT7 1NN. -1-