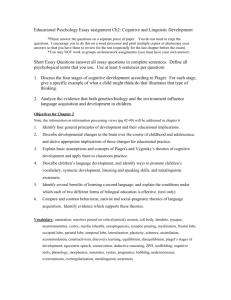

Piaget's Cognitive Development Theory Overview

advertisement

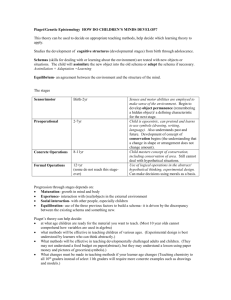

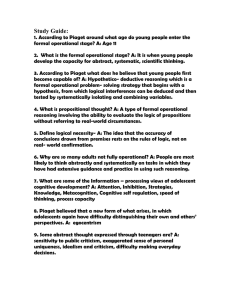

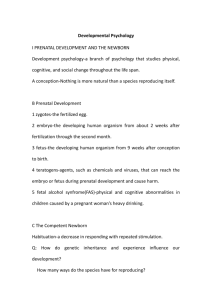

Piaget Cognitive Theory 1 Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development Theorist: Jean Piaget Biography Jean Piaget (1896-1980) was a Swiss biologist who revolutionized the concept of how children come to know. From an early age Piaget was interested in the world around him and involved in scholarly pursuits. He published several papers during his teen years about birds and mollusks. His first publication was at the young age of 11 about a rare albino sparrow. This was the beginning of a long scientific career during which Piaget would write over sixty books and hundreds of articles. He earned a Ph.D. in natural sciences in 1918 from the University of Neuchatel, Switzerland, and completed post doctoral studies in psychoanalysis the next year. Although his career began in began in the field of natural sciences, he also developed his interests in philosophy, and psychoanalysis. He worked for a time with Theodore Simon, coauthor of the Binet-Simon intelligence scale (Plucker, 2007). Throughout the course of his career he was a faculty member and researcher at the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute, professor of education and psychology at the University of Geneva, University of Lusanne, the Sorbonne of Paris, and many other distinguished institutions. Piaget dedicated his life to investigating the question of “How does knowledge grow? (Plucker, 2007)." Through mainly descriptive, qualitative research methods, Piaget developed an inductive process which revealed children’s logic and flaws in their answers to questions which became a signature mark of Piagetian research (Valsiner, 2005). In the late 1960s as Piaget’s publications were translated into English, his work came to the attention of American psychologists. Soon after education professionals recognized the momentous impact his cognitive development theory would have on developmental psychology and education (Elkind, 1974). Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive Piaget Cognitive Theory 2 development unlocked the secrets of the developmental process of human learning often concealed by the endearing, and sometimes exasperating, illogical reasoning of childhood. Theory of Cognitive Development Piaget’s theory puts forward the questions of how infants, children and adolescents organize their thoughts. In the development of his theory Piaget developed simple tests to children of different ages though which patterns of logical reasoning errors emerged. He developed four stages which describe the expected patterns of reasoning and cognitive perspectives from birth through adolescence. These four stages are sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operations, and formal operations (O’Donnell, Reeve & Smith, 2009, Piaget, 1932/1997)). The last stage begins at adolescence and carries on through adulthood. Although there are many complex aspects in which Piaget describes the mental processes and patterns that occur during cognitive development, the focus here will be on the cognitive processes which lead to application of Piaget’s theory for adolescent and adult development. Piaget included four mental operations His four stages of cognitive development explain the qualitative developmental changes which occur in children’s perceptions, understandings and how they operate in their environment (Woolfolk, 2008). These stages are outlined in Figure 1 (O’Donnel, Reeve, Smith, 2009). Some of the terms and definitions associated with Piaget’s theory are listed in figure 2 (Woolfolk, 2008). Piaget believed that cognitive structures arise as a result of a natural reorganization of what Piaget called logical structures (Piaget 1932/1997). This logical structure reorganization is influenced by the individual’s experiences with the environment (Elkind, 1974). Piaget gave a specific name to these logical structures: schemes. The individual’s ability to reorganize schemes Piaget considered a type of adaptation. Children’s, as well as adult’s, response to change through Piaget Cognitive Theory 3 new experiences and cognitive challenges to beliefs are at the heart of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. How a person responds to change is explained in the process of equilibriation (Wolfolk, 2008). The foundation of Piaget’s cognitive theory rests to upon the process of equilibration. It is through equilibriation that cognitive conflict, as a result of change or when experience is contradicted by one’s existing way of thinking, is resolved. Equilibration is a cycle in which an individual starts with a scheme which is in equilibrium. A scheme can be defined basic cognitive structure for organizing information. Schemes are generalizable and repeatable mental operations for behavior or concepts (O’Donnell, Reeve & Smith, 2009). When an individual has a set scheme one could call it a habit, a plan, routine or belief. A schema could be a simple as how to grasp chess piece or as complex as a strategy to beat an opponent in chess. Through out one’s life schemes either stay the same or change. The process of equilibriation occurs when one chooses to keep their scheme the same, known as assimilation, or when one chooses to change their scheme, known as accommodation (Piaget, 1932/1997). When new information is incorporated or integrated into an existing scheme without changing it, Piaget considered that assimilation. Because the scheme basically stays the same, not much learning takes place. Learning occurs when accommodation happens. Accommodation occurs when a scheme is adjusted or adapted to fit the new information or context (Wolfolk, 2008). Throughout development we utilize untold schemes in the operation of our world. When one has a stable scheme one is in equilibrium. When that is challenged the result is cognitive conflict, which Piaget called disequilibrium. To regain balance and return to equilibrium one will either return to the stable scheme through assimilation, or adapt the scheme through accommodation. The journey from equilibrium to disequilibrium and back to equilibrium Piaget Cognitive Theory 4 (through the action of accommodation or assimilation) is the process of equilibriation (O’Donnell, Reeve & Smith, 2009). The process of equilibriation is the mechanism by which one forms new ways of thinking (Elkind, 1974). Major Publications Authored by Jean Piaget (Plucker, 2007) Piaget, J. (1950). Introduction à l’Épistémologie Génétique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. Piaget, J. (1961). La psychologie de l'intelligence. Paris: Armand Colin (1961, 1967, 1991). Online version Piaget, J. (1967). Logique et Connaissance scientifique, Encyclopédie de la Pléiade. Inhelder, B. and J. Piaget (1958). The Growth of Logical Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence. New York: Basic Books. Inhelder, B. and Piaget, J. (1964). The Early Growth of Logic in the Child: Classification and Seriation. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Piaget, J. (1928). The Child's Conception of the World. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Piaget, J. (1932). The Moral Judgment of the Child. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co. Piaget, J. (1952). The Child's Conception of Number. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Piaget, J. (1953). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Piaget, J. (1955). The Child's Construction of Reality. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.Piaget, J. (1971). Biology and Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Piaget, J. (1995). Sociological Studies. London: Routledge. Piaget, J. (2001). Studies in Reflecting Abstraction. Hove, UK: Psychology Press. Piaget Cognitive Theory 5 Report Prepared by: Cindi H. Fries, Oklahoma State University, Fall 2008 References Elkind, D. (1974). Children and Adolescents: Interpretive essays on Jean Piaget. New York, Oxford University Press. O’Donnell, A., Reeve, J., & Smith, J. (2009). Educational psychology: Reflection for action (2nd ed). Hoboken, Wiley & Sons. Piaget, J. (1997). The moral judgement of the child. (translated by M. Gabian). New York: Free Press Paperbacks. (originally published in 1932). Plucker, J. A. (2007). Jean Piaget Swiss Biologist and Child Psychologist. Retrieved September 12, 2008 from http://www.indiana.edu/~intell/piaget.shtml Valsiner, J. (2005). Participating in Piaget. Society, 42 (2), 57-61.Retrieved from EBSCO Host September 11, 2008. Woolfolk, A. (2008). Educational psychology (10th ed). Boston, Pearson Piaget Cognitive Theory 6 Figure 1 Piaget's Stages of Cognitive Development Approximate Age and Grade Level Stage Primary Schemas Major Developments Sensorimotor During infancy, behavior is sensory (touching) and motor (grasping). Infants do not think conceptually but instead use their sensory and motor capacities to gain a basic understanding of their environment and construct sensorimotor coordinations. Infants create behavioral schemas. Through object permanence, infants learn that objects continue to exist when they are out of sight. 0–2 years Infancy 2–7 years Preschool, early elementary school Preoperational Children use symbolism Language develops rapidly. (language, images) to represent Children become various aspects of their imaginative in play. environment. Thought is prelogical, perception bound, and egocentric. 7–11 years Late elementary school Concrete operations Children acquire mental operations and apply them to solve concrete problems in front of them. No longer misled by physical appearances, children use their mental operations to reason. Adolescents think about thinking. They use mental operations to consider unseen hypotheses and solve abstract problems. Adolescents become capable of systematic, deductive, and inferential reasoning, which allows them to consider many possible solutions to a problem and choose the most appropriate one. 11 years and older Middle school Formal and high operations school (O’Donnell, Reeve & Smith, 2009) Piaget Cognitive Theory 7 Figure 2 Terms associated with Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development Basic Foundation Terms: Schemes: Mental systems or categories of perception and experience Operations: Actions a person carries out by thinking them through instead of literally performing the actions. Assimilation: Fitting new information into existing schemes Accommodation: Altering existing schemes or creating new ones in response to new information Equilibration: Stage Sensorimotor Preoperational Search for mental balance between cognitive schemes and information from the environment. Age Range 0-2 2-7 Terms of Major Stage Achievements ____ Object Permanence: The understanding that objects have a separate, permanent existence. Semiotic Function: The ability to use symbols – language, pictures, signs or gestures – to represent actions or objects mentally Operations are limited by: Egocentrism: Assuming that others experience the world the way you do Concrete Operations7-11 Decentration: Focusing on more than one aspect at a time Reversibility: To think through a series of steps, then mentally reverse the steps and return to the starting point. Arranging objects in sequential order according to one aspect, such as size, weight, volume or value. Seriation: Conservation: Formal Operations 11+ (Woolfolk, 2008) Principle that some characteristics of an object remain the same despite changes in appearance. Hypothetico-deductive reasoning: Problem solving strategy in which identifies all factors that might affect a problem and then deduces and systematically evaluates specific solutions.