Theories_of_Cognitive_Development.doc

advertisement

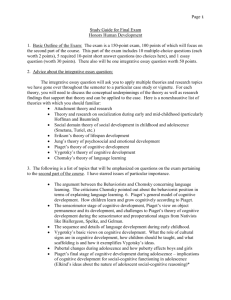

Cognitive Development Theories, etc. PIAGET’S LEARNING THEORY OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT According to Piaget, some students are just not ready to learn the concept that you may want to teach. For example, you may want to teach the causes of the Civil War and begin by asking your students why thy think the war broke out in 1861. But suppose your students responded with, “When is 1861?” Obviously their concept of time is different from your own. They may think, for example, that in time they may become the same age of an older sibling, or they may confuse the present with the past. The point is they are just not ready to learn this concept. Underlying Piaget’s theory is the assumption that we constantly strive to make sense of the world. HOW DO WE DO THIS? Piaget says we make sense of the world in four ways: 1. Biological maturation or the unfolding of biological changes that are generally programmed in each human at conception. Parents and teachers have little impact on this cognitive development, except to be sure that children are well nourished and healthy. Piaget refers to this unfolding as four stages of cognitive development. These stages include: a. Sensorimotor (0-2 years) – where the child begins to make use of imitation, memory, and thought. It is here that the child recognizes that objects do not cease to exist when they are hidden and begins their growth from reflex actions to goal-directed activity. b. Preoperational (2-7 years) – where the child gradually develops use of language and ability to think in symbolic form. It is here that the child is able to think operations through logically in one direction; however, the child has great difficulty seeing another’s point of view. c. Concrete Operational (7-11 years) – where the child is able to solve hands-on problems in logical fashion. Where they understand laws of conservation and they are able to classify and seriate. It is here that a child understands reversibility. d. Formal Operation (11-adult) – where the child is able to solve abstract problems and becomes more scientific in their thinking. It is this stage where the young person develops concerns about social issues. 2. Activity or the ability to act on the environment and to learn from it. When a child’s coordination is reasonably well developed, for example, they may play on a seesaw and from that experienced learn the concept of balance. As the child explores, tests and observes, he/she eventually organizes information and is likely to alter his/her own thinking process at the same time. 3. Social Transmission where the child learns from others and receives the knowledge offered by our culture. The amount that children or anyone, for that matter, can learn from social transmission varies according to their stage of cognitive development. 4. Equilibration, or the act of seeking balance. Piaget assumes that all people search for balance between their cognitive schemes and the information they receive from the environment. If the scheme does not produce balance, then disequilibrium exists, and the person becomes uncomfortable. This motivates the person to seek a solution to the problem and continue their search until equilibration is achieved. How teachers use Piaget’s Theory: Teachers can use Piaget’s theory of cognitive development to understand students’ thinking and to match instructional strategies to students’ abilities. His theory can also be very helpful in understanding how children make sense out of their world and how teachers can establish conditions where children construct their own knowledge. His theory, however, has been criticized because children and adults often think in ways that are inconsistent with the notion of invariant stages. It also appears that Piaget underestimated a child’s cognitive abilities and underestimated cultural factors in child development. These critics often point to work of Vygotsky as an example of a theory of cognitive development that does include the important role of culture. VYGOTSKY’S THEORY OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT Vygotsky placed much or emphasis than Piaget on the role of culture, schooling and especially language in cognitive development. In fact, Vygotsky believed that language in the form of private speech (talking to yourself) guides cognitive development. In his theory, students talk themselves through problems and learning tasks. Like Bruner, he believed in scaffolding or supporting the learner during the learning task with clues, reminders, encouragement, breaking the problem down into steps, providing examples or anything else that would aid the student to grow in independence. For Vygotsky, assisted learning was more than a method; it was the foundation upon which the student built higher mental processes such as problem solving. Like Piaget, he believed that conditions where students are seeking balance and resolution to a problem enhances learning. He called this condition the AONE OF PROXIMAL DEVELOPMENT; Piaget would have labeled it disequilibration. The difference is that Vygotsky and Bruner would have provided much more timely, appropriate guidance and support from teachers and other students called scaffolding and assisted learning. MASLOW’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS FOR LEARNING Maslow suggested that humans have a hierarchy of needs ranging from lower-level survival and safety to higher level needs for intellectual achievement, learning, and what he called “self-actualization.” This is the term that Maslow used for self-fulfillment, the realization of one’s human potential. Maslow’s Hierarchy in Ascending Order: 1. physiological needs 2. safety needs 3. belonging and love needs 4. esteem needs 5. need to know and understand 6. aesthetic needs 7. self-actualization needs 2 BRUNER’S DISCOVERY LEARNING Bruner emphasized the importance of understanding the structure of the subject being studied, the need for active learning as the basis for true learning. He suggests that teachers can nurture intuitive thinking and discovery learning by encouraging students to make guesses based on incomplete data and then confirm or disprove the guesses systematically. After learning about ocean currents and shipping industry, for example, students would be shown old maps of three harbors and asked which one became a major port. Students would then check their answers through research. While this may sound like constructivism, it is not. Bruner is very careful to label his theory GUIDED DISCOVERY especially for students in secondary schools. In guided discovery, the teacher provides direction, has objectives, and expects students to end up where she intends. She readily responds to their questions and, in the end provides the correct answers for her students. The point is that students are presented with intriguing questions, baffling situations, or interesting problems: Why does the flame go out when covered? Why does this pencil bend when placed in water? In stead of explaining how to solve the problem, the teacher provides material and encourages students to make observations, form hypotheses, and test solutions. Feedback must be given at the optimal time along with teacher reinforcement. DAVID AUSUBEL’S RECEPTION LEARNING Ausubel’s view of learning offers an interesting contrast with Bruner’s Discovery Learning theory. According to Ausubel, students learn through reception rather than discovery. Concepts, principles, laws, rules, and values are presented and understood, not discovered. He stresses that teachers should present a highly organized and focused lesson if students are to learn well. He also stresses, what he calls, Meaningful Verbal Learning of ideas and information in a carefully organized context which demonstrates how the ideas, concepts and information relates. Rote memorization is not considered meaningful learning. His theory of teaching is called Expository Teaching. This is where teachers present materials in a carefully organized, sequenced, and somewhat finished form and students thus receive the material in the efficient way. Unlike Bruner, Ausubel believes that learning should proceed, not inductively but deductively – from the general to the specific. ADVANCED ORGANIZERS Optimal learning occurs when there is a fit between what the student already knows and what is to be learned. To make this fit more likely, Ausubel says the teacher should always begin with an ADVANCED ORGANIZER. This is an introductory presentation of the concept being taught and the context in which it will be taught. This presentation should be broad enough to encompass all the information that will follow. The function of the Advanced Organizer is to provide scaffolding for the new information. Textbooks often contain advanced organizers. 3 MADELINE HUNTER’S DIRECT INSTRUCTION FOR LEARNING 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Clear and specific objectives Set and focus Content (concepts, laws and law-like principles, rules, values) Checking for understanding Guided Practice Independent Practice Evaluation BARAK ROSENSHINE’S DIRECT INSTRUCTION MODEL FOR LEARNING 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Academic focus Teacher directed Group instruction Demonstration-practice-feedback Teach to mastery BENJAMIN BLOOM’S TAXONOMY FOR LEARNING Bloom accounts for the variance between students that are learning and students who are not in his model. He then provides taxonomy of learning. This taxonomy can be used to help teachers write objectives, make assignments, and to ask questions. By changing the very form, the teacher moves her objective, assignment, and questions from lower order to higher order. This taxonomy, from lower to higher order, is below: 1. Knowledge 2. Comprehension 3. Applications 4. Analysis 5. Synthesis 6. Evaluation 4 WEINER’S THEORY OF ATTRIBUTION LEARNING Students attribute their success or failure to three dimensions: locus (internal or external), stability (stays the same or can change), and responsibility (whether the person can control the cause or not), He classifies these dimensions as: 1. Internal or external 2. Stable or unstable 3. Controllable or uncontrollable Whatever the label, a sense of control, choice as self-determination is critical if people are to feel intrinsically motivated. When students come to believe that events and outcomes in their lives are mostly uncontrollable, they have developed learned helplessness. This learned helplessness appears to cause three types of student deficits: 1. motivational 2. cognitive 3. affective ATTRIBUTION AND STUDENT MOTIVATION Most students try to explain their failure to themselves. When a successful student fails, they often make internal-controllable attributions: they misunderstood the directions, or simply lacked the background knowledge, or did not study hard enough. MOTIVATIONAL PROBLEMS arise when students attribute failure to stable uncontrollable causes. These students may become resigned to failure, depressed and almost helpless – what the teachers usually call UNMOTIVATED. These students respond to failure by focusing even more on their own inadequacy; their attitude toward schoolwork may deteriorate even farther. Apathy is the logical reaction to failure if students believe the causes of their failure are stable, unlikely to change, and beyond their control. ATTRIBUTION AND ACHIEVEMENT 1. Mastery Oriented – high need for achievement, low fear of failure 2. Failure Avoiding – high fear of failure 3. Failure Accepting – expectation of failure 5 GAGNE’S CONDITIONS FOR LEARNING Verbal information - Relate new material to learner’s framework Provide meaningful context Provide imagery Give clues for effective retrieval Intellectual Skills Stimulate recall of prerequisite skills Provide applications Provide novel situations Cognitive Strategies - Describe the strategy Demonstrate the strategy Provide opportunities for practice Motor Skills Provide mental rehearsal and demonstration Repetition with correction Attitudes Provide respected model(s) Enact positive behavior When learner enacts, provide reinforcement GAGNE’S INSTRUCTIONAL EVENTS 1. Gaining attention 2. Informing learner of the object 3. Stimulate recall of prior learning 4. Provide learning content 5. Elicit performance 6. Provide feedback 7. Assess performance 8. Provide retention and transfer 6 HOWARD GARDNER’S MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCE LEARNING THEORY In 1983, Howard Gardner of Harvard wrote a book entitled, Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. In this book, Gardner outlines his theory of multiple intelligences. There are two fundamental propositions central to MI-Theory: (1) Intelligence is not fixed. We have the ability to develop the intellectual capacity of our students. (2) Intelligence is not unitary. There are many ways to demonstrate intelligence. There is not just general intelligence, but rather multiple intelligences. Everyone has each intelligence and a unique pattern of multiple intelligence. His theory, of course, conflicts with mainstream psychological theory of intelligence. Mainstream theory assumes a relatively fixed I.Q. throughout life within a standard error of measurement and argues for a general intelligence. Gardner set out in search of multiple intelligences. He believed that for anything to be considered intelligence, it had to meet three conditions. An intelligence must include: 1. Skills enabling individuals to resolve genuine problems. 2. The ability to create an effective product. 3. The potential for finding of creating problems. Gardner originally selected several intelligences that met these conditions, and has recently added an eighth, the Naturalist. The eight intelligences identified by Gardner include: 1. Verbal/Linguistic 2. Body/Kinesthetic 3. Logical/Mathematical 4. Visual/Spatial 5. Musical/Rhythmic 6. Interpersonal 7. Intrapersonal 8. Naturalist 7 WILLIAM GLASSER’S CHOICE THEORY While not specifically a theory of learning, Glasser’s Choice Theory fits into the category or learning environment as it affects learning. He believes that we have disenfranchised students in schooling – we “do school” to kids. His recommendations are that we reenfranchise students by giving them much more choice in their educational endeavors. This does not imply that student have a free-for-all in their choice of curriculum but rather that within the standard or district-required curriculum, teachers find ways to provide meaningful choice activities for students. In this way cooperative learning as well as consideration of theories such as Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences attain more prominence in the classroom. He categorizes teachers as “boss teachers” or “lead teachers.” Boss teachers use rewards and punishment to coerce students to comply with rules and complete required assignments. Glasser calls this “leaning on your shovel” work. He shows how high percentages of students recognize that the work they do – even when their teachers praise them – is such low-level work. Lead teachers, on the other hand, avoid coercion completely. Instead, they make the intrinsic rewards of doing the work clear to their students, correlating any proposed assignments to the students’ basic needs. Plus, they only use grades as temporary indicators or what has and hasn’t been learned, rather than a reward. Lead teachers will “fight to protect” highly engaged, deeply motivated students who are doing quality work from having to fulfill meaningless requirements. Glasser’s list of basic needs which dictate student behavior (and adult behavior as well) are: 1. basic needs 2. love and belonging 3. fun 4. freedom 5. power He feels that, in order for students to be successful and engaged learners, teachers need to recognize these needs and find strategies and methods to structure activities that will satisfy them in the classroom (as they are often satisfied in extra-curricular activities). 8