David Hojman: Network Learning, Award Winning Performance and

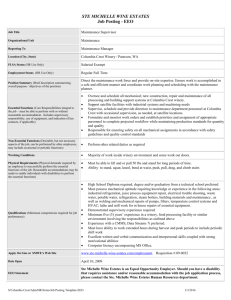

advertisement

Network learning and principal-agent conflict: Wine-makers in Chile’s Colchagua Valley David E. Hojman The School of Management University of Liverpool Liverpool L69 7ZH UK Fax: 44 (0) 151 795 3001 / 3005 / 3720 E-mail: JL33@liv.ac.uk Abstract Chile’s Colchagua Valley is both a geographical cluster of wineries and a dynamic learning network of wine-making professionals. A principal-agent problem arises in that the latter knowledge network is frowned upon by owners and top managers. Whereas highly skilled employees are after maximising quality, firms are interested in profits. Individual, personal success as a world-class expert is worth more to each professional, than to the respective winery. This conflict is compounded by traditional, authoritarian industrial relations. Regression results confirm that expert network activity is a very poor predictor of award-winning international performance, or profits. Keywords: Networks, Principal-agent, Wine, Chile JEL: D82, D85, L14, M54, O13, Q16 1 1 Introduction Do Chilean wine-makers cooperate with each other? If they do, is this reflected in their respective performances? This paper addresses the apparent contradiction between Farinelli (2003), Visser (2004) and Visser and De Langen (2005) on the one hand, and Giuliani (2003a, b) on the other hand, regarding the alleged presence or absence of inter-firm cooperation among Chilean wine-makers. These authors have all made substantial contributions to recent scholarship on Chilean wine, but there seems to be a fundamental disagreement between them. Farinelli (2003, p. 22) refers to ‘the very pronounced fragmentation, isolation and individualism of the entrepreneurs’, and argues that ‘the decade of “easy” exports did not stimulate the mix of cooperation-competition which characterises most dynamic clusters’. The PowerPoint presentation of her paper (www.utoronto.ca/onris/ChilePresentation.ppt) mentions ‘scarce interaction among wine producers (and) practically no inter-firm cooperation’. Visser (2004) and Visser and De Langen (2005, p. 15) agree. The experts they interviewed emphasised ‘the “extremely” individualist attitudes of Chilean wine-makers, their “short-term mindedness”, and bias towards understanding better … competition than … cooperation’. Absence of trust would be a key problem (p. 16). 1 However, Giuliani (2003a, b, c) has found high levels of cooperation, in the form of a healthy network of knowledge flows, among wine-making professionals in Chile’s Colchagua Valley. Superficially, this seems to be precisely the opposite from what was described in the previous paragraph. Moreover, this discovery by Giuliani may not be a local characteristic unique to the Colchagua geographical cluster, since the group of firms formed by those she calls ‘innovators’ (which also have high absorptive capacities and are open to intra- and extra-cluster knowledge exchanges) ‘… is predominantly composed of large national firms, which are leading the process of technological renovation in the country by investing in applied research also jointly with national research institutions’ (2003b, p. 23). This paper argues that in fact there is no contradiction between Farinelli and Visser and De Langen on the one hand, and Giuliani on the other. They are really talking about different things. The former are talking about the attitudes of the wine-making firms, companies, wineries, employers, top management, CEOs, executives, or owners (in the rest of this paper, these terms are used as equivalent), whereas the latter has been observing the attitudes of employees (or some employees). 2 Thus, according to Giuliani, there is plenty of evidence of network activity in Colchagua. Many Colchagua Valley wines have also been doing very well in international competitions, such as the International Wine Challenge in London. So, is the former causing, or at least making a contribution towards the latter? This is one of the questions this paper addresses. There are at least three types of inter-firm knowledge flows in the Colchagua Valley. The first one is family-based: it takes place between members of the 2 same family. These are relatives, either close or distant, who own, or are part of the top management of, different wineries (Duijker, 1999). The second type of knowledge transfer takes place through consultants. The same consultant works for two or more firms, sometimes simultaneously (Duijker, 1999; Tapia, 2001; Schachner, 2002). The consultant shares his or her knowledge (the same knowledge) with two or more firms. In some cases, he or she also increases his or her own knowledge, or acquires new local information, from a particular winery, which is eventually passed on to another winery. The third type of knowledge transfer is possibly the most interesting one. Apart from it being identified by Giuliani, no study has concentrated on it before. It is based on an informal network of professionals or skilled employees. This is a knowledge network that is more active, or dynamic, than what many of the respective companies would wish. Participation in the network is more advantageous for the employee, than for the winery that employs him or her. Network participation increases the professional’s human capital stock, improves his or her technical performance, enhances his or her standing (and social capital stock) with fellow network members, and therefore ultimately adds to his or her prestige and lifetime income stream. In contrast, the net impact of network activity on a particular winery’s profits may be positive or negative. The firm wants its expert to receive information, not to give it away. Not only that, but ideally the firm also prefers for the expert to receive only that information which will make him or her more productive in his or her current job, but not the sort of information that will make the expert more attractive as a potential employee to competing firms. Some evidence of both these network flows of knowledge, and the related principal-agent conflict, are conveyed in the case study by Echecopar, Fetters and McDermott (2004): ‘The upgrading of the Chilean wine industry benefited greatly from competition, but not less importantly, by cooperation. Miguel Torres [the Spanish oenologist and investor] was the first to share knowledge, but he was not the only one … Chilean wine-makers not only changed jobs often from one winery to another, thus diffusing knowledge in their new firms, but they also did consulting for several other firms.’ And: ‘… [Douglas] Murray … and [Aurelio] Montes’ knowledge and creativity gave rise to some winemaking experiments at San Pedro [one of the large traditional Chilean wine producers] which were not looked on positively by an administration who saw these experiments as distractions and preferred to focus on the bottom line.’ 3 The professional informal network identified by Giuliani is largely a personal network, a network of individuals, not a network of companies. The next section describes the main characteristics of the current wine boom in Chile, and some of the specific features this boom has adopted in the Colchagua Valley. Section 3 briefly summarises the relevant academic discussion on geographical clusters and knowledge networks. The fact that no satisfactory answer has been provided to explain the motivation behind giving away knowledge to a competing winery in the Colchagua Valley is addressed in Section 4. The principal-agent conflict at the root of this particular case is discussed in Section 5. Another key aspect of the general picture is the prestige, or celebrity status, which has recently been given to 3 successful wine-making experts. This is addressed in Section 6. Three testable hypotheses are put forward in Section 7, and the respective variables for empirical work are defined in Section 8. Section 9 presents and discusses the results from multiple regression tests and Section 10 concludes. 2 The wine boom in Chile and Colchagua By the beginning of the 1990s, Chile presented exceptionally favourable conditions for a boom in the production and exports of quality wine. These included practically perfect soil and climate conditions, economic and political stability, a welcoming attitude towards foreign investment, institutional transparency and lack of corruption, an export- and innovation-supportive public sector, and a cheap and reasonably well-trained labour force. Vineyard plantations increased from 50,000 hectares in 1994 to 109,000 in 2002. Wine exports rose from 400,000 hectolitres in 1990 to 3.6 million in 2002. Traditionally the largest export market had been Latin America. However, by 2002 about 80 percent of wine exports were going to Europe and North America (SAG, 2003). In 2003, Chile represented 2.6 percent of world production and 5.6 percent of world exports (Costa, 2004). Wine has been made in the Colchagua Valley for several hundred years, and good wine (by international competition standards) for at least a century. However, Colchagua joined the current renaissance of Chilean wine relatively recently, although it has been progressing at a very fast rate since then. 4 At least partly, the particular characteristics of the Colchagua network may have to do with the local culture (Pilon and DeBresson, 2001; CORFO, 2004a). This culture is fully open to external influences, for example from the parent company in the case of foreign direct investment or joint ventures. There has been foreign direct investment in wine making in Colchagua by, among others, Billington, Kendall Jackson, Mondavi, Marnier Lapostolle, Guelbenzu, Lurton, Bodegas y Bebidas, and Rothschild (see Appendix 1). The Colchagua Valley is also open to external influences, in that some local wineries are subsidiaries of larger national companies, for example of older and larger wineries from the Maipo Valley and elsewhere (Concha y Toro, Santa Rita, San Pedro, Errazuriz). There are also some extremely talented individuals, in both wine-making and other entrepreneurial activities (Aurelio Montes, the Lurton brothers, or Carlos Cardoen, the industrialist and local hotel and museum owner). Finally, there are local wine-making firms, mostly long established, which are fully or largely based on Colchagua (Bisquertt, Casa Silva, MontGras, Luis Felipe Edwards, Viu Manent). All of these contribute to make the Colchagua Valley special and, according to some, also to make its wines different from, say, wines from the Maipo Valley. Maybe the local culture has always been different, but in any case it has certainly been evolving in a particular, distinct way since the current renaissance of Chilean wine started in the mid 1980s. In areas not directly related to vine planting and wine production, there is more cooperation between firms in Colchagua, than elsewhere in Chile. Good examples of this are the local initiatives on 4 wine tourism, and the private restoration and running of an old steam train, activities which are much more interesting and innovative than in the rest of the country (Guia de Vinos de Chile, 2005). 3 Geographical clusters and knowledge networks There may be some disagreement or confusion in the literature as to what exactly clusters and networks are, and what exactly they do. Martin and Sunley (2003, Table 1, p. 12) have put together ten different definitions of a ‘cluster’, all of them published in the five-year period 1996-2001. A careful distinction between ‘networks’ and ‘clusters’ has been offered by Maskell and Lorenzen (2004, Table 1, p. 996). But several authors have expressed their unwillingness to adopt these two concepts without proper, intellectually coherent and generally accepted definitions. Concern has also been expressed at the use of these concepts for largely unsupported policy prescriptions (Breschi and Lissoni, 2001; Markusen, 2003). The otherwise very comprehensive survey of Latin American clusters by Altenburg and Meyer-Stamer (1999) does not even mention Chilean wine. Possibly this is not because the authors are not aware of it, but because this particular case does not conform to their own definition of what a cluster is. In this paper, we will use the word ‘cluster’ to describe a physical concentration or agglomeration of firms in a particular geographical area. These firms are active in the same or related productive sectors, and they possibly trade with, or are related to each other, vertically or horizontally. Some of the companies in the cluster are small but there may also be large ones in it. As shown by Ellison and Glaeser (1999), an important reason for the existence of many geographical clusters is the possibility of taking advantage of local natural resources and conditions. This is possibly one of the key factors behind the wine-making cluster in the Colchagua Valley (Tapia, 2001; Schachner, 2002). It has been convincingly shown by Giuliani (2003a, b, c) that the Colchagua Valley is not only a geographical cluster, but also a knowledge network. New knowledge, sometimes leading to productive innovations, may be locally generated or imported from outside the cluster. In either case, this knowledge flows between firms, or between professionals working for different firms, from the ‘knowledge leader’, or ‘technological gatekeeper’ (whoever generated it, or had the initial contact with a knowledge source outside the Valley), towards others. 5 4 What motivates the knowledge giver? A question that has not been answered adequately is, why should those relatively more advanced firms in the Colchagua cluster be prepared to share their superior knowledge with other, less sophisticated producers? What is the motivation of the knowledge giver? Giuliani and Bell (2005, pp. 61-62) argue that: 5 ‘… willingness to engage in unreciprocated knowledge transfer to other local firms may reflect … positive externalities … In a wine area, such as Colchagua, which is currently investing in achieving international acknowledgement for the production of high quality wines, the improvement of every producer in the area is likely to generate positive marketing-related externalities for the whole area, and these may outweigh the possible cost …’ However, there are some problems with this interpretation. Could such positive externalities really be that substantial? Will firm A, the knowledge leader, eventually benefit from increased recognition for the whole Colchagua Valley, itself generated by the fact that firm B, the knowledge follower, is becoming a better producer? Surely it makes more sense for A to try to achieve international recognition for its own product, rather than devoting the same amount of effort and resources to try to achieve recognition for the entire Valley, and then wait for any positive externalities to come back to benefit A? Moreover, if B can eventually make a contribution to the Valley’s reputation, possibly it would be because it has become so good that now it may represent competition for A? Presumably, if B does not become really good (as good as A, or almost, or even better), then it cannot make a contribution to the Valley’s reputation? Or maybe B is shamefully bad, and the knowledge transferred from A to B is limited, just enough to stop B from damaging the Valley’s reputation? Is the information being transferred from A to B of only limited value? It would be in the interest of A to help B to improve, but not very much, just enough. Possibly B’s improvement could not be kept under control by A, if the knowledge transferred is of great, or greater, value? But then, surely it would not be long, either before B realises that it is not getting the most valuable information, or before it uses what is getting fully and then it requires better knowledge? All of these outstanding questions suggest that relying only on positive externalities as the explanation, not only requires strong assumptions, but it also makes the resulting system highly unstable. In the words of Breschi and Lissoni (2001, p. 980): ‘… it might be that what standard methodologies …, data sets … and concepts … suggest to be pure externalities will turn out to be, on more careful scrutiny, knowledge flows that are mediated by market mechanisms’. A more convincing explanation than Giuliani and Bell’s (2005) is that at least some of the knowledge transfer may take place, without the top management or owners of the relevant firms being aware of it. At least some of those engaged in the knowledge transfer (skilled and semi-skilled employees, junior and middle management, professionals, agronomists, viticulturists, oenologists, administrators, etc) may be doing it, because it is convenient for themselves, and even if the respective company would disapprove, if it knew about it. Some interesting evidence in this connection is offered by Giuliani herself, in a previous paper (Giuliani, 2003a): 6 ‘… much of the knowledge flowing between firms takes place via such professionals, while owners and managers are quite reticent in releasing information’ (p. 10). Her interviews: ‘were directed to the oenologists or agronomists operating in the plant or vineyard … [and] … employees working in more direct contact with the productive activity: eg the farmer himself in the case of individual grape growers or the cellar man’ (p. 14). In the course of her fieldwork, she became aware that: ‘in some cases, local personnel are strictly asked by the parent firm not to release any information’ (p. 23). As mentioned before, also authors such as Farinelli (2003, p. 22), Visser (2004) and Visser and De Langen (2005) have argued that Chilean wineries are ‘individualistic’ and show a propensity to ‘free ride’. These views are confirmed by Echecopar, Fetters and McDermott (2004) and Bjork (2005) (see above). All of this evidence would be in direct contradiction with the belief that positive externalities are all important, and that the local knowledge leaders are aware of it and act accordingly. 6 5 The principal-agent question So, there is here a principal-agent issue. 7 The Colchagua local knowledge network seems to exist, despite the opposition of the firms’ (or some firms’) top management and owners. The network is stronger and more active than what these top management and owners would wish. For the skilled employees or professionals in the Colchagua wineries, an active, dynamic network is more important than for their companies. A particular firm may be either better off or worse off as a result of network activity, depending on whether it is a net giver (to potential competitors) or a net receiver of useful network-transmitted knowledge. 8 But the skilled employee or professional is always, or almost always, better off as a result of network activity, provided that his or her winery does not catch him or her committing what many firms would interpret as an act of disloyalty. As an information receiver, the professional directly benefits. He or she learns something new, which is a net addition to his or her human capital stock, and his or her performance at work (or output) improves. As an information giver, the professional is doing someone else a favour that will eventually be reciprocated. A shared identity between the experts in different companies is also likely to contribute to the network’s success. Knowledge flows will be more dynamic if I see the person at the other end as equal to me, if he or she is ‘one of us’ (Akerlof and Kranton, 2005). Some authors have interpreted this role for 7 identity as another story of ‘social embeddedness’, or ‘strength of weak ties’ (Uzzi, 1997; Granovetter, 2005). As Giuliani (2003c, p. 22) puts it: ‘The oenologists and agronomists operating in the local area tend to interact cognitively more when they have a common background and share the same commitment to the improvement of the understanding of local viticulture and oenology. They release critical information and cooperate in problem solving because of commonality-diversity elements in their knowledge bases. Of course, … such knowledge sharing is stimulated both by mutual trust and by the expectancy that they will receive feedback sooner or later.’ But at least some of this knowledge transfer has to remain undisclosed, with only the respective giver and receiver being aware of it. Many networks rely on trust (Gossling, 2004). Trust is essential in the Colchagua Valley for two reasons: because reciprocity is expected sometime in the future, and because some knowledge transfers must be, if not secret, at least very discrete. Giuliani starts one of her papers (2003c) with a quote from Krugman: ‘Knowledge flows are invisible; they leave no paper trail by which they may be measured and tracked…’ This is very convenient when at least one of the partners in the transaction does not want his or her employer to learn about it. To keep it secret is a powerful reason for face to face contacts. Many networks require physical, face to face contact (Urry, 2004). In the Colchagua Valley this may be particularly important, since participants may often prefer their exchanges to be verbal rather than written. 9 The need for discretion is reinforced as an ongoing process of consolidation and concentration among wineries advances (see Appendix 1 for some examples). The Colchagua Valley network is informal, but this does not make it less effective. Principal-agent conflict is not unheard of in informal knowledge networks (Von Hippel, 1987, p. 302). An additional incentive for professionals and skilled employees to participate in this Colchagua Valley informal knowledge network is that there are already many links between wineries because of family connections (Duijker, 1999). There are also individual consultants who have advised different wineries over the years, or are currently advising them, even two of them or more at the same time (Duijker, 1999; Tapia, 2001; Schachner, 2002). Both of these facts combine to make it possible for a general manager or owner, despite not being an expert, to know more than the expert himself or herself, which would leave the latter in a rather uncomfortable position. A final reason for this informal, reciprocity-expecting, trust-based knowledge network is that, increasingly, successful wine-making experts are being treated as ‘celebrities’, ‘stars’, or ‘super-heroes’. This makes the individual accumulation of capital stock, and the recognition and prestige attached to it, all important. 8 6 The ‘celebrity’ wine-making expert as star Increasingly, Chilean wine-making experts (arguably the best, but many of them) are being seen and hailed as celebrities. In the spring of 2005, The Times and The Sunday Times carried tabloid-size adverts for The Sunday Times Wine Club, offering a mixed case of twelve bottles, in which the only Chilean bottle was presented as: ‘Merlot from a winemaking “genius”: Vina Tarapaca Merlot 2004, Central Valley … As the first UK merchant to buy from Chile, The Club enjoys special access to wines from acclaimed makers such as Sergio Correa’. This personality cult is becoming widespread. All the Chilean wines sold by Marks and Spencer in the UK carry the individual wine-making expert’s name in the label (both the individual oenologist’s name, and that of the company which employs him or her, are given). 10 There is only one exception, a Chilean firm which, instead of giving persons’ names, prefers to say that its wine was made by a ‘team of Chilean and Australian makers’. According to Eduardo Chadwick (2003), chairman of Vina Errazuriz, ‘there is a new generation of talented young viticulturists and winemakers … who have received international training and are passionate about quality’ (see Appendix 1). The Wine Spectator in April 2005 had an article on Chilean wine (Molesworth, 2005), in which oenologists of the wineries Concha y Toro, Los Vascos and Antiyal (Enrique Tirado, Marco Puyo and Alvaro Espinoza, respectively) were explicitly mentioned. The article also had a colour photograph of Casa Lapostolle’s wine-making expert, Jacques Begarie. That issue of the Wine Spectator also carried a full-page advert by Vina Santa Ema, with a large photograph (and the name) of their own wine-making expert, Andres Sanhueza. The name and a colour photograph of Vina Ventisquero’s winemaking expert (Felipe Tosso) may also be found in their full-page advert in Decanter, June 2005. In the same publication, another winery is described as going through ‘troubling times’, having lost their experts twice during 2003 (both are named). Luckily, either another expert (number three) was already in place or was rapidly hired, and readers can see his photograph (Richards, 2005). Every year, the Guia de Vinos de Chile presents its ‘Best WineMaking Expert of the Year’ award (won by Marcelo Papa in 2005). The Guia also chose the ‘Best Wine-Making Expert of the Decade’, for its tenth anniversary in 2003 (Ignacio Recabarren). The names of many other ‘celebrity’ oenologists, with the respective firms they work for, may be found in Tapia (2005). The winner of the trophy for the best wine in show in the second year of the Wines of Chile Awards, Vina Falernia Alta Tierra Syrah 2002, Elqui Valley, was described as made by not one but three talented wine-making experts: Aldo Olivier, Giorgio Flessati and Jean-Marc Sauboua (Wine International, May 2005, p. 20). Why are so many Chilean wine-making experts being hailed as celebrities, or stars? The first reason is that everyone, and wineries in particular, are 9 becoming aware of how important specialist knowledge can be. This is not only general knowledge, but also knowledge about local, micro conditions. Such knowledge is not easy to come by, and the best of it may always be in short supply. The best skills and experience are scarce. A second reason is that this is a marketing exercise by the wineries. By saying explicitly, ‘this wine was made by Mr. X (or Ms. Y)’, they are implicitly suggesting that ‘this wine is so good, so special, that we must tell you who made it’. But there is even a third reason, namely, that the practice is also supported by the experts themselves. Such an explicit acknowledgment of a person’s skills is, in terms of prestige, an important aspect of their remuneration packages. However, not all wineries are equally happy to embrace this practice. As mentioned before, one of the suppliers of Chilean wines to Marks and Spencer will not go along with it. Maybe this particular employer feels that such explicit acknowledgment will represent an excessive increase in the expert’s remuneration package, and/or it will make him or her a desirable target for headhunting by other wineries. Another interesting characteristic of this particular labour market is that winemaking experts tend to move around substantially from one employer to the next (see Appendix 1). Many experts do not seem to last a long time in their jobs. This could be at least partly a result of booming demand for their services. Before 1980, there were less than 200 oenologists who had graduated from Chilean universities in the country (Farinelli, 2003, p. 10). Another 50 graduated during the 1980s. By the end of that decade, the Chilean wine boom had already started, and over 300 students graduated during the 1990s. By 2004, the Chilean Association of Oenologists had 620 members (Miranda, 2004). So, this high rate of migration from winery to winery may be caused by a temporary imbalance between supply and demand, which will be corrected eventually. But there is an alternative explanation. Migration may be caused by firms’ (or some firms’) unwillingness to accept active participation by their experts in knowledge networks such as the Colchagua one, which management consider disloyal. This problem may be compounded by the traditional nature of industrial relations and human resource management in Chile, which is paternalistic and authoritarian (Hojman and Perez, 2005). As part of their professional development, winemaking experts must work with different soils, local microclimates and grape varieties. But in an ideal world they should be able to do this without having to change jobs. The characteristics of the current network are not necessarily stable. The long-term process of convergence towards equilibrium is affected by several trends (Callander and Plott, 2005). Some of the large wineries (this is not possible for a small winery on its own) may opt for engaging in the modernisation of their industrial relations and human resource management, and for providing an internal environment where scope economies associated to diversity (of everything, from natural conditions to technological packages to experts’ personalities) can be fully exploited. This is equivalent to trying to internalise the positive externalities generated by their experts’ network participation. Other large wineries may opt for publicly de-emphasising the role played by their experts, which is compatible with attempting to preserve 10 traditional, paternalistic or authoritarian management practices. Smaller wineries may try different forms of association. The best experts may try to become independent, their own bosses, by starting their own businesses. They may also go for non-conventional forms of partnership with the most dynamic among the large firms. Many examples are presented in Appendix 1 (see also CORFO, 2004b, c). 7 The model and hypotheses A formal theoretical model of the Colchagua Valley network, which explicitly includes the determinants of the professional’s satisfaction, the level of network activity, the winery’s profits, and the resulting principal-agent conflict, is presented in Appendix 2. Building on the discussion of previous sections, it is possible to suggest three hypotheses which may be tested empirically. Hypothesis 1: Network activity and average quality in the domestic market are positively related. However, network activity may not be the only (or even the most important) determinant of quality, because the impact of network activity on quality is weakened by the attempts by the winery to maximise profits. Following from Hypothesis 1, network activity and overall presence in the domestic market (defined as the product of multiplying average quality times the number of different wines offered, or ‘product range’) may also be positively related. However, network activity may not be the only (or even the most important) determinant of domestic presence, not only because of the winery’s profitmaximising drive, but also because network activity may also affect the product range in different, specific ways. The present discussion concentrates on overall domestic presence, rather than product range, because the former rather the latter is possibly more likely to affect international presence and international success (via factors such as financial strength and scope economies). Hypothesis 2: The impact of network activity on international success is small. In particular, network activity may not be as important as overall domestic presence, or other factors. More generally, there may be an inverse relationship between the impact of network activity on a particular variable, and the effect of that particular variable on international success, or profits. Hypothesis 3: The impact of network activity on profits is small. The rest of this paper is devoted to the empirical testing of these hypotheses and to discussing the results. 11 8 Variables and data Three indicators of network activity in the Colchagua Valley, by individual winery, are available (Giuliani, 2003a). They are actor degree centrality (DECE), actor closeness centrality (CLOS) and actor betweenness centrality (BETW). Complete definitions are given and discussed in Wasserman and Faust (1994, Chapter 5). Briefly, DECE is defined as an actor’s number of direct, one-to-one, no-intermediary links with other actors or network members (as a ratio of the maximum possible). CLOS is about both direct and indirect links. It measures the number of intermediaries an actor has to go through, on average, in order to reach all the other network members. The lower that average, the greater the actor’s closeness to the rest of the network will be. Finally, BETW measures the number of times actor B is an inevitable intermediary between two other actors (say A and C) who are not themselves in direct contact, when A and C want to get in touch with each other using the shortest possible way (ie., via the smallest number of intermediaries). The actual value of indicator BETW for actor B is given by the average number of times B is the inevitable intermediary, when all possible couples of actors (including A and C, but not only them), different from B, are trying to get in touch with each other. A higher value of BETW means that actor B is more ‘in the middle’, or is more of a ‘gatekeeper’, or has more ‘interpersonal influence’ (see Wasserman and Faust, 1994, pp. 171, 179, 186 and 191 for examples). Colchagua wineries also have individual values for absorptive capacity (ABCA) and extra-cluster openness (EXCL). These indices have been defined and their values computed by Giuliani (2003a, pp. 22, 28). The variable ABCA includes the educational levels of skilled workers, separating national from foreign sources and first degrees from masters and doctorates; national and international work experience; previous jobs, separating national from international employers; and four levels of research experiments. Variable EXCL is a scale measuring technical support and training received from, and joint experiments with, national and international knowledge sources external to the Colchagua Valley, in the previous two years. Each winery’s average quality in the domestic market (GUIQ) has been calculated using the highly respected Guia de Vinos de Chile (2005). The Guia includes all the wines in the domestic market (over 900), with their respective individual blind-assessed quality ratings. Colchagua is overwhelmingly a red-wine producing area. So, only red wines were considered in our tests. Also, wines were included only when the region of origin was given as ‘Colchagua’, or ‘Colchagua Valley’, or sub-areas of it, such as ‘Santa Cruz’. Some wineries have production facilities in Colchagua but they choose not, or are not legally allowed, to give ‘Colchagua’ as their region of origin (instead, they use ‘Central Valley’ or ‘Rapel Valley’). Such wines were also excluded from the relevant statistical tests. The Guia’s quality ratings rank from 1 (the lowest) to 4-plus. Some wines in ranks 2, 3 and 4 may also be ‘highlighted’, or designated as 2-plus, 3-plus and 4-plus 12 (meaning ‘distinguished in its own class’). This gives a scale with seven levels, from 1 to 4-plus. For purposes of our statistical work, this scale was converted to one going from 1 to 7. In other words, the old scale ‘1, 2, 2-plus, 3, 3-plus, 4, 4-plus’ becomes ‘1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7’. A winery’s overall presence in the domestic market (GUIX) was defined as the product of multiplying the winery’s average quality GUIQ by the number of its wines, or product range, GUINU. For example, assume that winery W has two red wines from Colchagua listed in the Guia (GUINU=2), with quality rankings of 3 and 4-plus. In our new 1-to-7 quality scale, these are equal to 4 and 7, respectively, giving a total of 11 (GUIX=11). Variable GUIQ is equal to 5.5 (GUIQ = GUIX / GUINU = 11 / 2). This is a real life example and its importance will become apparent in the next paragraph. The last variable to be defined is a winery’s performance in London’s 2004 International Wine Challenge (IWC; see Wine International, 2004). London’s ratings for wines which win awards are, in increasing order of quality, Seal of Approval, Bronze, Silver and Gold. For purposes of our statistical tests, they were converted to the numerical scale 1, 2, 3 and 4. For example, winery W got two Seals of Approval and one Bronze. These translate to 1, 1, and 2, respectively, in our numerical scale. We add them up, to get the value of our variable IWC for winery W, which is 4 (1 + 1 + 2 = 4). 11 Incidentally, note that winery W, which had only two wines in the domestic market, won three awards in London (and it may have submitted more than three wines). Winery W kept at least one of its wines, and maybe more, exclusively for the international market. Conversely, some wineries with domestic sales (and therefore mentioned in the Guia) chose not to take part in London, or took part but won no awards (and therefore were not mentioned in Wine International, 2004). Rankings of the top Colchagua wineries in 2004-2005, according to the three indicators GUIQ, GUIX and IWC, are presented in Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all the variables in the model are given in Table 2. 9 Empirical estimation and results The proposition that a winery’s network activity (or more accurately, network activity by a winery’s expert or experts) in the Colchagua Valley may affect the average quality of the respective wines in the domestic market is tested in Table 3. These multiple regressions also look at the possible role of absorptive capacity and extra-cluster openness. According to the Table 3 results, of all three indicators of network activity, both DECE and BETW could be making a contribution towards determining GUIQ. However, the respective t statistics are relatively small (about 1.4-1.6), by the usual significance levels. Although the sign is always positive as expected, the t statistics do not confirm unequivocally that a relationship between either DECE or BETW on the one hand, and GUIQ on the other, is present (but they suggest it). In contrast, the Table 3 regressions confirm that EXCL and GUIQ are positively 13 linked. Extra-cluster openness is offering a better explanation than network activity. Thus, Table 3 offers only weak support for Hypothesis 1. However, it would be impossible to claim from Table 3 that network activity damages GUIQ. It is certainly possible to conclude that, if there is a relationship at all between network activity and GUIQ, it is most likely that it will be positive. 12 The possible impact of network activity on a winery’s overall domestic presence, GUIX, is examined in Table 4. The quality of these fits is not as high as in Table 3. Less than a third of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by this model (as opposed to almost two thirds in Table 3). Still, Table 4 offers strong evidence of a statistically-significant, positive-sign link between CLOS and GUIX. However, since GUIX is defined as the product of multiplying GUIQ by GUINU (the number of wines in the domestic market, or product range), and since CLOS played no role in explaining GUIQ (see Table 3), it follows that CLOS explains GUIX, only because it is positively related to GUINU. So, network activity does indeed affect domestic presence, although this takes place via product range. Incidentally, product range is very low as a competitive priority for Chilean wineries. Winery executives interviewed by Foster et al (2002, pp. 36-38) ranked product range as their competitive priority number 10, out of a list of ten possibilities. Network activity in Colchagua helps with product range, but, in the views of winery executives, product range as a priority comes last, after everything else. It is obvious that the sample interviewed by Foster et al (2002) was very different from that interviewed by Giuliani (2003a, b, c). 13 The possibility of a relationship between network activity and international success (IWC) is examined in Tables 5 and 6. Table 5 presents regressions exploring the impact of network activity, absorptive capacity, extra-cluster openness, and GUIX, on IWC. Since GUIX itself may be endogenous, and a function of network activity, some of these regressions were estimated using instrumental variables (TSLS). According to the Table 5 results, the most important determinant of IWC is GUIX. There may or may not be an ABCA effect (in most cases the t statistic is about 1.6). If there is a BETW impact at all (the respective t statistic is often, but not always, as low as -1.9), this impact would be negative. So, either there is no impact of network activity on IWC, or this impact is negative. But this is only after having controlled for a separate impact of GUIX (and through GUIX, CLOS) on IWC. The Table 6 specifications are similar to those in Table 5, except that in Table 6 GUIX is not introduced as a separate regressor. This is because, if GUIX depends indeed on network activity, then the estimated coefficients for the network activity variables in Table 6 will reflect both the direct impact, and the indirect impact via GUIX. Since GUIX is not an explicit part of the Table 6 model, the sample can now be enlarged by adding wineries with no domestic presence. This increases the sample size from 17 to 23. The indicator CLOS is statistically significant. However, the adjusted coefficient of determination is very small. This model explains less than 5 percent of the variance in the dependent variable. Moreover, there is a very large risk of omitted variable bias, which takes credibility away from the estimated coefficient for CLOS. Both Tables 5 and 6 confirm that Hypothesis 2 should be accepted. Since it is 14 most likely that GUIX makes only a small contribution to explaining profits, and given that Hypothesis 2 has been accepted, Hypothesis 3 is also accepted. A slightly different interpretation of these multiple regression results is also possible. Given that the best fit in Table 4 (Regression 4.4) explains only 30 percent of the variance in GUIX, it could be argued that GUIX is largely independent from network activity. Therefore, GUIX could be introduced as an independent regressor in the Table 5 model. This means that the best fit in Table 5 is Regression 5.2, obtained using ordinary least squares (OLSQ). This would give us a fit explaining about 60 percent of the variance in IWC. The most important determinant of IWC would be GUIX. Possibly ABCA would also play a role (the respective t statistic is 1.6). But two of the network activity variables, CLOS and BETW, seem to be affecting IWC negatively. How, or why could this happen? There are several possibilities. Maybe quality notions at home and abroad are very different. Or maybe network activity is generating ‘lock-in’, or ‘small world’ negative effects (see Granovetter, 2005, for some examples). Or maybe ‘excessive’ network activity is encouraging uniformity across firms, and therefore mediocrity, rather than distinctiveness. Or maybe not all the knowledge flowing in the network is of top quality or conducive to top quality performance. And so on. In any case, this alternative interpretation would also confirm Hypotheses 2 and 3. Summarising, the empirical results suggest that: First, the quality of Colchagua wines in the domestic market seems to be largely explained by a winery’s extra-cluster openness. Possibly, network activity may help, but this could not be confirmed by our tests. Second, network activity contributes to a winery’s domestic presence, but it is not the only factor and it may not be the most important one. Moreover, this effect takes place via product range, a variable the wineries are not particularly interested in. And third, network activity seems to make no contribution to a winery’s international success (at least when the latter is defined as performance in London’s International Wine Challenge). In fact, its impact may actually be negative. 10 Conclusions There cannot be any doubt that there is an informal knowledge network of wine-making professionals in the Colchagua Valley. This network is active and dynamic. However, it makes sense to ask what is it there for. The empirical results suggest that network activity in Colchagua: a) may not be a crucial factor for domestic quality; b) it helps with a winery’s domestic presence, but for the wrong reasons; and c) its effect in terms of international award-winning performance is negligible, or even counterproductive. 15 So, given these rather modest roles both at home and abroad, why is there a Colchagua network at all? It is not surprising that many wineries are not enthusiastic about it (and some are extremely unhappy). The most likely explanation confirms the central idea of this paper. The Colchagua network is a network of professionals, but not of their employers. Individual participation by a particular employee may be against the wishes, implicit or explicit, of the respective company. A principal-agent conflict has emerged from the fact that what is the best for one of them is not the best for the other. It may be very frustrating for wine-making experts that the network does not make a stronger contribution to quality. This failure is highlighting a large gap in time horizons, a clash between the expert’s lifetime development and career ambitions, and the winery’s short-term profit maximising aims. In a more positive vein, the Colchagua network is suggesting the presence of a new type of scope economies. A winery may be large enough to be able to offer each expert the possibility of working with, and learning from, different geographical regions, soil conditions, microclimates, and grape varieties, and interaction with other experts, without having to change jobs or give away valuable company information. This winery may be prepared to acknowledge publicly the important contribution that each one of its experts is individually making. In that case, such a winery would benefit from internalising most of the positive externalities generated by the network. Unfortunately, this option is open to large wineries only. Small and medium-sized companies cannot take advantage of it. Notes 1 In a similar vein, Bjork (2005) argues that wine production in Chile, and foreign direct investment in Chilean wine-making, have generated few spillovers. 2 In addition to the authors mentioned before, see also Del Pozo (1995) and Vergara (2001) for the historical context. 3 Conflict between quality maximising and profit maximising in wine making is not unique to Chile. See Morton and Podolny (2002) for related evidence in the Californian wine industry. 4 For example, the results of a blind tasting of 106 Chilean Cabernet Sauvignons, organised by the magazine Decanter and published in their June 2005 issue, show how fast Colchagua wine-makers have progressed (or are progressing). The only winner of a Decanter Award (5 stars) was from Colchagua (Montes Alpha Apalta Vineyard 2002). Also one of the two 4-star wines came from Colchagua (Vina Sutil Reserva Pablo Neruda 2002), together with 10 out of 41 wines receiving the more modest 3-star accolade. 5 Another crucial aspect of the theoretical discussion is that networks do not remain unchanged, but, on the contrary, they tend to develop, evolve or 16 converge towards particular or specific forms of equilibrium (Callander and Plott, 2005). This is also true in the Colchagua Valley (or in Chilean winemaking more generally). A key related, or complementary, perspective is the notion that economic transactions take place in, and therefore economic outcomes are affected by, social structures (Granovetter, 2005). The original Question 4 of Giuliani’s field research work (Giuliani, 2003b, p. 15) was: ‘Could you mark … those with whom you have collaborated …?’. However, in the Giuliani and Bell (2005, p. 54) article, based on the same field research work, this wording has been changed to: ‘Could you mark … those with whom this firm has collaborated …?’. This change would be harmless if ‘you’ (the expert being interviewed) and ‘this firm’ were exactly the same thing. But they are not. Giuliani and Bell (2005), by ignoring the fact that the Colchagua network is one of professionals, different from a hypothetical network of firms, represents a step backward in relation to Giuliani (2003b). Giuliani and Bell (2005, p. 51) explicitly acknowledge their assuming perfect identification between each interviewee and his or her firm: ‘… (L)ocal knowledge flows within “cognitive subgroups” of professionals (and, therefore, firms) …’ Such identification is misleading, as Giuliani (2003a, b, c) herself had previously shown. 6 7 A typical principal-agent problem refers to the contractual arrangement between a firm (the principal) and its employee (the agent) in the presence of asymmetric information. Profits depend on the employee’s effort, but this effort cannot be monitored by the firm. In the absence of adequate incentives, effort will not be maximised (or will be suboptimal) and profits will suffer. A typical ‘optimal solution’ would link the wage to profits. The employee would be paid more when profits are high, and less when profits are low (Akerlof and Kranton, 2005, pp. 13-14). For wine-making in Colchagua, instead of ‘low effort against high effort’, the employee’s choice would be ‘to pass on or not to pass on knowledge to another firm’s employee’. However, the Colchagua story is more complicated for two reasons. First, the typical Colchagua winery does not know the exact nature of the relationship between network participation by its employee, and the firm’s profits. And second, the motivation of the wine-making expert may be more complex than just a simple textbook choice between income and leisure. A formal model is presented in Appendix 2. 8 Even if the aggregate impact of the network on the whole of the Colchagua Valley is positive, the individual winery typically does not know whether the specific impact of the network on itself will be positive or negative. There is also uncertainty for the typical firm in that, even if the short-term specific impact of the network on the firm may be positive, the long-term effect may not. 9 This need for face to face contact in the Colchagua Valley, in order to keep (at least part of) the knowledge flow invisible to (at least) one of the two owners or top managers, has nothing to do with the knowledge being ‘tacit’. For a discussion of the role of knowledge ‘tacitness’ in the study of clusters, see Lissoni (2001). 17 10 It is possible that Marks and Spencer may insist on getting and publishing the individual expert’s name, as a form of insurance, or pressure, against excessive personnel changes in its Chilean suppliers, and with them, wild quality swings. Our IWC indicator is one of ‘overall presence’, rather than ‘average quality’. However, it differs from GUIX, not only in that it is international as opposed to domestic, but also in that any wines which did not win awards were not included in the IWC ranking. In terms of IWC ranking, not participating, and participating without winning an award, are equally bad. 11 12 The fact that the link between network activity and wine quality is not stronger is possibly a source of disappointment to many experts (and it could be another reason for the high rate of expert migration from winery to winery). 13 According to Table 4, the variable EXCL seems to have a negative-sign impact on GUIX (which is not significant at the usual levels in all the regressions). References Akerlof, George A. and Kranton, Rachel E. (2005), Identity and the Economics of Organisations, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 1, Winter, pp. 9-32. Altenburg, Tilman and Meyer-Stamer, Jorg (1999), How to Promote Clusters: Policy Experiences from Latin America, World Development, 27, 9, September, pp. 1693-1713. Bjork, Ida (2005), Spillover Effects of FDI in the Manufacturing Sector in Chile, Master’s thesis, Lund University, School of Economics and Management. Breschi, Stefano and Lissoni, Francesco (2001), Knowledge Spillovers and Local Innovation Systems: A Critical Survey, Industrial and Corporate Change, 10, 4, December, pp. 975-1005. Callander, Steven and Plott, Charles R. (2005), Principles of Network Development and Evolution: An Experimental Study, Journal of Public Economics, 89, 8, August, pp. 1469-1495. Chadwick, Eduardo (2003), Chile: A Success Story, but Where Do We Go from Here?, Annual Lecture, Wine and Spirit Education Trust, www.wset.co.uk. CORFO (2004a), Colchagua Tierra Premium, 24 August, www.corfo.cl. CORFO (2004b), Profo Itata Wines: Nuevas Tecnologias para Vinedos Finos, 7 July, www.corfo.cl. 18 CORFO (2004c), Destacamos en la Metropolitana: Integracion de Vinas, 19 April, www.corfo.cl. Costa, Victor (2004), La Vitivinicultura Mundial y la Situacion Chilena en 2004, Servicio Agricola y Ganadero, www.sag.gob.cl. Del Pozo, Jose (1995), Vina Santa Rita and Wine Production in Chile since the Mid-19th Century, Journal of Wine Research, 6, 2, pp. 133-142. Duijker, Hubrecht (1999), The Wines of Chile, Utrecht, Spectrum – Segrave Foulkes. Echecopar, German, Fetters, Michael and McDermott, Tom (2004), Entrepreneurship, An Engine for Innovation, www.uai.cl/p4_centros/site/asocfile/ASOCFILE120040427104311.pdf. Ellison, Glenn and Glaeser, Edward L. (1999), The Geographic Concentration of Industry: Does Natural Advantage Explain Agglomeration?, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 89, 2, May, pp. 311-316. El Mercurio online, www.emol.com. Farinelli, Fulvia (2003), Technological Catch-up and Learning Dynamics in the Chilean Wine Industry, paper presented to the Conference on Innovation and Competitiveness in the New World of Wine, Niagara, 12 November, www.utoronto.ca/onris/PaperChile.doc. Foster, William, Beaujanot, Andre and Zuniga, Juan Ignacio (2002), Marketing Focus in the Chilean Wine Industry, Journal of Wine Research, 13, 1, April, pp. 35-42. Giuliani, Elisa (2003a), Knowledge in the Air and its Uneven Distribution: A Story of a Chilean Wine Cluster, paper presented to the DRUID Winter Conference, Aalborg, 16-18 January, www.druid.dk/conferences/winter2003/Paper/Giuliani.pdf. Giuliani, Elisa (2003b), How Clusters Learn: Evidence from a Chilean Wine Cluster, paper presented to the EADI Workshop, Novara, 30-31 October, www.unipmn.it/eventi/eadi/papers/papers/giuliani.pdf. Giuliani, Elisa (2003c), Social Network Analysis: An Application in the Analysis of Knowledge Flows in Clusters of Firms, www.unisi.it/santachiara/aree/conf_phd_econ2003/conference_siena/papers/ giuliani.pdf. Giuliani, Elisa and Bell, Martin (2005), The Micro-Determinants of Meso-Level Learning and Innovation: Evidence from a Chilean Wine Cluster, Research Policy, 34, 1, February, pp. 47-68. 19 Gossling, Tobias (2004), Proximity, Trust and Morality in Networks, European Planning Studies, 12, 5, July, pp. 675-689. Granovetter, Mark (2005), The Impact of Social Structure on Economic Outcomes, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 1, Winter, pp. 33-50. Guia de Vinos de Chile (2005), Santiago, Turismo y Comunicaciones, 12th Edition. Hernandez, Alejandro and Vallejos, Claudio (2005), Estudio para el Desarrollo de un Programa de Apoyo a la Innovacion en el Industria Vitivinicola, CORFO, www.corfo.cl. Hojman, David E. and Perez, Gregorio (2005), Cultura Nacional y Cultura Organizacional en Tiempos de Cambio: La Experiencia Chilena, Academia – Revista Latinoamericana de Administracion, 35, November. Lissoni, Francesco (2001), Knowledge Codification and the Geography of Innovation: The Case of Brescia Mechanical Cluster, Research Policy, 30, 9, December, pp. 1479-1500. Markusen, Ann (2003), Fuzzy Concepts, Scanty Evidence, Policy Distance: The Case for Rigour and Policy Relevance in Critical Regional Studies, Regional Studies, 37, 6-7, August/October, pp. 701-717. Martin, Ron and Sunley, Peter (2003), Deconstructing Clusters: Chaotic Concept or Policy Panacea?, Journal of Economic Geography, 3, 1, January, pp. 5-35. Maskell, Peter and Lorenzen, Mark (2004), The Cluster as Market Organisation, Urban Studies, 41, 5-6, May, pp. 991-1009. Miranda, Valentina (2004), Interview with Klaus Schroder, President of the Chilean Association of Oenologists, www.enologo.cl. Molesworth, James (2005), Chile’s Maturing Quality, Wine Spectator, April, pp. 126-130. Morton, Fiona M. Scott and Podolny, Joel M. (2002), Love or Money? The Effects of Owner Motivation in the California Wine Industry, Journal of Industrial Economics, 50, 4, December, pp. 431-456. Mytelka, Lynn K. and Goertzen, Haeli (nd), Vision, Innovation and Identity: The Emergence of a Wine Cluster in the Niagara Peninsula, mimeo. Pilon, Sylvianne and DeBresson, Christian (2001), Local Culture and Regional Innovative Networks: New Hypotheses and Some Propositions, University of Quebec at Montreal, Centre de Recherche en Gestion, Working Paper 212001. 20 Richards, Peter (2005), Maipo: The Road Less Travelled, Decanter, June, pp. 50-58. SAG (Servicio Agricola y Ganadero) (2003), Panorama de la Vitivinicultura Chilena in 2003, www.sag.gob.cl. Schachner, Michael (2002), The Next Napa?, Wine Enthusiast, March, www.winemag.com. Tapia, Patricio (2001), The Wines of Colchagua Valley, Santiago, PMC Pinnacle – Planetavino. Tapia, Patricio (2005), Guia de Vinos Chilenos (Descorchados), Santiago, Origo. Urry, John (2004), Small Worlds and the New ‘Social Physics’, Global Networks, 4, 2, April, pp. 109-130. Uzzi, Brian (1997), Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness, Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 1, March, pp. 35-67. Vergara, Sebastian (2001), El Mercado Vitivinicola Mundial y el Flujo de Inversion Extranjera a Chile, CEPAL, Red de Inversiones y Estrategias Empresariales, Serie Desarrollo Productivo 102. Visser, Evert-Jan (2004), A Chilean Wine Cluster? The Quality and Importance of Local Governance in a Fast Growing and Internationalising Industry, http://econ.geog.uu.nl/visser. Visser, Evert-Jan and De Langen, Peter (2005), A Chilean Wine Cluster? The Importance and Quality of Cluster Governance in a Fast Growing and Internationalising Industry, http://econ.geog.uu.nl/visser. Von Hippel, Eric (1987), Cooperation between Rivals: Informal Know-how Trading, Research Policy, 16, 6, December, pp. 291-302. Wasserman, Stanley and Faust, Katherine (1994), Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications, Cambridge University Press. Wine International (2004), International Wine Challenge, October. Wine International (2005), First Taste, May, p. 20. 21 Table 1 Rankings of top Colchagua Valley wine-makers (red wines only) Guia de Vinos de Chile 2005: average quality (GUIQ) Guia de Vinos de Chile 2005: overall domestic presence (GUIX) International Wine Challenge 2004 (IWC) Lapostolle Casa Silva Casa Silva Los Vascos Montes JOINT: LF Edwards MontGras Viu Manent Emiliana JOINT: Bisquertt Cono Sur Santa Helena Montes MontGras Caliterra Caliterra Viu Manent Santa Ines de Martino Casa Silva Siegel Crucero JOINT: Apaltagua Bisquertt Cono Sur JOINT: Caliterra Los Vascos Apaltagua Ventisquero Santa Helena Lapostolle etc etc etc 22 Table 2 Descriptive statistics 2A Means and standard deviations of variables Variable Mean Standard deviation ABCA DECE CLOS BETW EXCL GUIQ GUINU GUIX IWC 0.379 5.412 6.897 4.041 1.592 3.048 4.353 13.29 6.176 1.029 4.459 2.183 3.912 0.843 1.149 2.978 9.584 10.06 2B Correlation matrix ABCA DECE CLOS BETW EXCL IWC GUIX GUINU GUIQ ABCA DECE CLOS BETW EXCL IWC GUIX GUINU 0.307 0.497 0.363 0.512 0.280 0.228 0.080 0.570 0.756 0.761 0.460 0.043 0.382 0.266 0.637 0.669 0.390 0.253 0.593 0.528 0.555 0.465 0.075 0.426 0.309 0.665 0.011 0.060 -0.194 0.761 0.742 0.653 0.152 0.896 0.366 0.008 The sample size is 17 23 Table 3 Average quality in the domestic market (dependent variable: GUIQ) Regressor 3.1 3.2 3.3 Constant 1.564 (2.690) 1.412 (4.922) 1.280 (5.783) ABCA 0.229 (1.084) 0.209 (1.225) DECE 0.055 (1.427) 0.046 (1.650) 0.044 (1.407) CLOS -0.029 (-0.295) BETW 0.073 (1.531) 0.071 (1.492) 0.081 (1.608) EXCL 0.632 (2.688) 0.641 (2.801) 0.754 (4.034) Estimation method OLSQ OLSQ OLSQ Adj R2 0.622 0.652 0.648 n 17 17 17 The t statistics are in parentheses. The standard errors and variance are heteroskedastic-consistent estimates 24 Table 4 Overall domestic presence, defined as average quality times the number of wines (dependent variable: GUIX) Regressor 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Constant -3.852 (-0.921) -3.265 (-0.993) -1.737 (-0.976) -3.390 (-1.852) ABCA -0.309 (-0.129) DECE -0.471 (-0.842) -0.445 (-0.716) CLOS 3.073 (3.385) 2.991 (2.616) 2.598 (3.558) 2.949 (6.642) BETW 0.563 (1.283) 0.558 (1.318) 0.341 (0.682) EXCL -2.298 (-1.340) -2.460 (-1.908) -2.677 (-2.240) -2.296 (-1.552) Estimation method OLSQ OLSQ OLSQ OLSQ Adj R2 0.141 0.212 0.257 0.299 n 17 17 17 17 25 Table 5 Performance in the International Wine Challenge: an explicit role for GUIX (dependent variable: IWC) Regr. 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Constant 2.851 (0.674) 3.821 (1.100) 2.972 (0.658) 3.954 (1.068) 3.285 (0.792) 0.250 (0.104) ABCA 2.698 (1.634) 2.926 (1.624) 2.707 (1.614) 2.948 (1.606) 2.837 (1.607) 2.402 (1.149) DECE -0.064 (-0.120) CLOS -1.338 (-1.386) -1.390 (-1.682) -1.435 (-1.266) -1.459 (-1.638) -1.115 (-0.700) BETW -0.625 (-1.193) -0.612 (-1.893) -0.643 (-1.172) -0.615 (-1.928) -0.597 (-1.885) -0.630 (-1.393) EXCL 0.613 (0.337) GUIX 1.010 (3.997) 1.001 (3.911) 1.042 (4.888) 1.027 (4.754) 0.896 (1.566) 0.569 (2.162) Estim. method OLSQ OLSQ TSLS TSLS TSLS TSLS Adj R2 0.518 0.596 0.518 0.596 0.595 0.562 n 17 17 17 17 17 17 -0.049 (-0.087) 0.686 (0.374) All the exogenous variables were used as instruments in Regressions 5.4 and 5.5, but they differ in that one of them uses also GUINU and the other does not 26 Table 6 Performance in the International Wine Challenge, excluding GUIX from the estimating equation (dependent variable: IWC) Regressor 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Constant 0.135 (0.032) 0.278 (0.067) 2.405 (0.435) -1.927 (-1.518) -2.442 (-1.851) ABCA 2.602 (0.877) 2.506 (0.873) 2.582 (0.898) DECE -0.333 (-0.583) -0.466 (-0.780) CLOS 1.556 (1.943) 1.537 (1.994) 0.900 (1.454) 1.430 (3.554) 1.162 (3.607) BETW -0.230 (-0.534) EXCL -2.148 (-1.101) -2.239 (-1.179) -2.444 (-1.322) -1.498 (-1.174) Estimation Method OLSQ OLSQ OLSQ OLSQ OLSQ Adj R2 -0.069 -0.014 0.014 0.013 0.046 n 23 23 23 23 23 27 Appendix 1: Some wineries, owners and experts Winery Domestic owner / coowner Agustinos Corpora Almaviva Concha y Toro San Pedro Altair Foreign owner / coowner Mouton Rothschild Chateau Dassault Anakena Antiyal Apaltagua * B Prats, P Pontallier Aresti Baron Philippe de Rothschild Billington * Mario Geisse Juan Fernando Waldele, Philippe Debrus (f Valdivieso), Jochen Dohle Calina * Errazuriz Lisa Denham Kendall Jackson (f Mondavi) Canepa * Carta Vieja Casablanca Lapostolle * Casa Silva * Casas del Bosque Casas del f? Felipe de Solminihac Billington USA Calama Carmen Ana Maria Cumsille Carmen Merino Michel Friou (f Lapostolle) Bisquertt * Botalcura Caliterra * Juan Ignacio Ramsay, Jose Henriquez? Tod Mostero Gonzalo Perez, Pascal Marti (f Almaviva), f? Bernard Portet Alvaro Espinoza Alvaro Espinoza Donoso family Aquitania Oenologist, viticulturist, consultant Santa Rita Santa Carolina Marnier Lapostolle Chateau 28 f? James Randy Ullom Rodrigo Banto, f? Ignacio Recabarren Paula Cifuentes, Ernesto Juisan Pilar Gonzalez, Matias Lecaros, f? Alvaro Espinoza, f? Jacques Boissenot Pascal Marti (f Almaviva) Max Ibanez, f Ignacio Recabarren Jacques Begarie, Michel Rolland Mario Geisse David Morrison, Camilo Viani Toqui Larose Trintaudon Clos Quebrada de Macul Concha y Toro Conde de Aconcagua Cono Sur * Cousino Macul Domaine Conte Domaine Oriental D Francisco El Principal Errazuriz Patrick Valette, Ignacio Recabarren Tamara de Baeremaecker, Marcelo Papa, Marcio Ramirez, Ignacio Recabarren, Enrique Tirado, Goetz von Gersdorf, Max Weinlaub Estampa Gonzalez Byass Concha y Toro Santa Carolina Adolfo Hurtado, Cecilia Padilla, Martin Prieur, Constanza Vicent Jose Miguel Ovalle, Jaime Rios, Matias Rivera Beringer Blass M Paoletti, R+L Wan Julio Valdivia Patrick Valette Sven Bruchfeld, f? Edward Flaherty, f? Pedro Izquierdo Estampa * Falernia F de Aguirre Gillmore Gracia Guelbenzu * Araucano * Haras de Pirque Huelquen La Fortuna La Rosa Leyda * Los Vascos * Concha y Toro Corpora Santa Rita Boisset Guelbenzu Spain Lurton Antinori (f Rothschild Laffite) Lourdes LF Edwards Matetic Miguel Torres f Alvaro Espinoza Torres Spain 29 Aldo Olivier, Giorgio Flessati, Jean-Marc Sauboua Lorena Veliz, f Carlos Andrade, f? Aurelio Montes Andres Sanchez (f Calina) Jose Henriquez? Cecilia Guzman, Alvaro Espinoza Gregorio Ferrada Sergio Traverso Jose Ignacio Cancino Rafael Urrejola Marco Puyo Jorge Martinez ‘Australian experts’, Nicolas Bizarri, f? JA Usabiaga, f? M Farmilo Rodrigo Soto Fernando Almeda Montes MontGras * Hartwig family Morande Odfjell Norwegian investor Penalolen Perez Cruz Perez Leon * Porta Corpora Portal del Alto * Quintay Ramirana Ventisquero Reserva de Caliboro Ignacio Recabarren German Lyon Boisset Francesco Marone Cinzano Irene Paiva, f Aurelio Montes, f? Jacques Lurton Pedro Izquierdo, Consuelo Marin, f? Pilar Gonzalez S Carolina * S Eliana S Laura * Vinedos de Jalon Andres Sanhueza San Pedro Adriana Cerda, Francois Massoc, Felipe Muller, Marcelo Retamal, f? Aurelio Montes Ernesto Jiusan, f? J+F Lurton Hartwig family S Monica S Rita Selentia * San Pedro Sena y Arboleda * Siegel * Sutil * Tamaya Errazuriz Bodegas y Bebidas (f Mondavi) Paz Lastra Carlos Gatica, Andres Ilabaca, Cecilia Pino, Cecilia Torres, Alejandro Wedeles, f Ignacio Recabarren Christophe Paubert, Francisco Ligero Edward Flaherty Pernod Ricard Jimena Egana Diego Garcia de la Huerta Carlos Andrade (f F de Aguirre) Sergio Correa, Cristian Molina, Sebastian Ruiz Flano, f Leonardo Contreras, f Santiago Margozzini Adriana Ceron, Robin Day, Stefano Gandolini Tarapaca Terra Andina / Sur Andino Jose Henriquez? Carolina Arnello Jorge Morande Aurelio Montes Jr S Pedro S Ema S Helena * S Ines de Martino * Victor Baeza Sven Bruchfeld, Santiago Margozzini, Paul Hobbs Eugenia Diaz Arnaud Hereu, Paul Hobbs Carmen 30 Terramater Canepa family Patrick Valette, Cristian Vallejo Terranoble Terravid Portal del Alto Tierra y Fuego Torreon de Paredes Undurraga * Valdivieso (f MataRomera) Swiss investors Yves Michel, Yves Pouzet Hernan Amenabar, f Aurelio Montes Brett Jackson Coderch family Ventisquero * Veramonte Via Wine Group Villard Vina Mar * Vinedos del Maule Emiliana * Franciscan Vineyards Coderch family Emiliana Tarapaca Felipe Tosso, Aurelio Montes Jr, Aurelio Montes Rafael Tirado, f? Jacques Boissenot Julian Grubb Villard Spain Viu Manent * William Cole William Fevre Ignacio Conca, Henri Marionnet Alejandro Hernandez W Cole USA W Fevre France Roberto Lavandero, Fernando Torres Tatiana Eneros, Alvaro Espinoza, Pablo Vergara Leonardo Contreras, Aurelio Montes Francois Massoc Sergio Hormazabal Note: Not all wineries are listed, but only those with the same domestic ownership for two or more wineries, or with foreign investment, or with known experts, or with red wine production in Colchagua. Experts were excluded when they were also the owners or co-owners. * It makes red wines in Colchagua f: formerly Sources: Duijker (1999), Tapia (2001, 2005), Chadwick (2003), Farinelli (2003), Guia de Vinos de Chile (2005), Hernandez and Vallejos (2005), Molesworth (2005), Richards (2005), El Mercurio online 31 Appendix 2: The model The professional’s satisfaction Utility U of the wine-making expert depends on his or her wage W, the contribution to his or her human capital stock, H, which is offered by the current job, and the prestige P that this job gives. The sign of each of these effects is positive. [1] U = U ( W, H, P ) U / W, U / H, U / P > 0 The contribution of the current job to the expert’s stock of human capital, H, is positively affected by the level of the expert’s individual participation in the knowledge network, N. Variable H may also depend on other factors, X, which are not relevant to the present discussion. [2] H = H ( N, X ) H / N > 0 The impact of N on H is positive, even if the expert is a net giver of information. The fact that, in the short term, the employee transfers more knowledge to others, than what he or she receives himself or herself, is not a problem. Although on balance in the short term he or she is giving more than what he or she is receiving, that knowledge which he or she is giving to someone else is not lost to the giver. He or she still keeps it. The giver is also expecting some reciprocity in the future. The expert’s prestige depends, with positive signs, on his or her stock of human capital and on his or her level of participation in network activity. [3] P = P ( H, N ) P / H, P / N > 0 The level of network activity Network activity is affected by human capital stocks, since knowledge flows need some absorptive capacity at both ends (Giuliani, 2003a, b, c). Network activity is also positively associated with the perception of identity I in network members, as in Akerlof and Kranton (2005). Cooperation benefits from the feeling that the person at the other end is ‘one of us’ (for example, we went to university together, or even to the same school, etc). On the other hand, if the expert is caught passing on information that the employer wants to keep private, to employees of other firms, the expert will become discredited in the eyes of the employer, and he or she may be accused of disloyalty, and 32 punished, dismissed or blacklisted. Therefore, the risk R of getting caught affects N negatively. [4] N = N ( H, I, 1/R ) N / H, N / I > 0 N / R < 0 The winery’s profits The overall presence of a winery in the domestic market, GUIX, is defined as the product of multiplying average quality GUIQ, by the number of different wines the company sells at home (or ‘product range’), GUINU. The names of these variables start with the three letters GUI because they all come from the Guia de Vinos de Chile (2005). [5] GUIX = GUIQ * GUINU Quality depends on the knowledge, or human capital stock, of the winemaking expert, and therefore ultimately on the level of network activity. But the product range depends on many other factors (Y), including the explicit decision to either concentrate on only one, or a small number of different products, or go for a much wider variety. Other possible determinants of GUINU may include historical aspects or path dependence, and the possibility to invest out of surpluses (and therefore, at a lower financial cost). The impact of N (network activity by the firm’s own expert) on both GUIQ and GUIX is expected to be positive, since network activity contributes to learning by the expert. [6] GUIQ = GUIQ ( N ) [7] GUIX = GUIX ( N, Y ) GUIQ / N, GUIX / N > 0 The winery’s profits are defined as the product of the sales volume V (including sales of award-winning wines and of wines for everyday consumption, both at home and abroad), times the average price p, minus all costs C. [8] = Vp - C Unfortunately, none of the four variables in Equation [8] is available. An alternative, approximate expression for the profit equation is given in [9]. Indicators such as the overall presence of the company in the domestic market, GUIX, and the degree of success in international competitions such as the International Wine Challenge in London, IWC, may be positively related 33 to . Other variables, including sales volumes and costs, are represented by Z. [9] = ( GUIX, IWC, N, Z ) / GUIX, / IWC > 0 The sign of the impact of the level of network activity N, / N, is not known. It may be positive or negative. For example, a particular firm may be a net receiver of information that is used to increase output, quality or sales, at little or no extra cost (which makes the sign positive). Alternatively, the firm may be a net giver of information that makes the competition stronger, or higher network activity may be associated with unconstrained search for quality that leads to booming costs, or higher network activity may contribute to erode other firm-specific advantages (all of which make the sign negative). Network activity makes the firm’s own expert more productive, but also more expensive, and puts him or her more in demand as both a network partner and a potential employee of other firms. Principal-agent conflict and multiple equilibria Typically, the professional benefits more from his or her own network participation, than his or her employer does. [10] ∂U / ∂N > ∂π / ∂N Depending on whether a particular company’s management style is traditional or not, on how badly the firm wants to keep a particular expert, on the company’s size, and on whether the firm sees network activity as a threat or an opportunity, multiple equilibria are possible. Most of the variables in Equations 1 to 10 are unobservable. However, there are several indicators for N (Guiliani, 2003a). Average quality in the domestic market, GUIQ, may be a good proxy for prestige P, although GUIQ applies to the winery, whereas P applies to the individual wine-making expert. 34