the common thread - Enlightenment Economics

advertisement

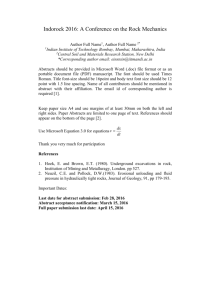

Corporate governance, public governance and global governance: the common thread Diane Coyle1 Working Paper, Institute of Political and Economic Governance, University of Manchester, http://www.ipeg.org.uk December 2003. The question of governance has catapulted to prominence in recent years. A search of news databases for references to ‘governance’ shows the number of uses of the word has been on an upward trend through the late 1990s but has exploded during the past 12 months or so [FIG 1]. However, the governance question arises in a number of different contexts: it is applied to corporations, governments and international agencies. The aim of this paper is to explore the links – if any – between corporate, public and global governance. In each context the growth of interest stems from the sense that there has been a governance crisis. This is perhaps clearest in the case of corporate governance where the timing of the preoccupation with governance questions in public debate is related to a series of high-profile corporate scandals. The most notorious are the huge US bankruptcies related to alleged frauds and undoubted executive greed – such as Enron (bankruptcy filing December 2001), Tyco (CEO indicted Jun 2002), WorldCom (bankruptcy filing July 2002) and Qwest (accounts restated by $1bn July 2002). However, the corporate misbehaviour and mismanagement of the late 1990s have not been confined to the US, as examples such as Philip Holzmann in Germany (bankruptcy filing March 2002), Vivendi in France (chief executive forced out July 2002), and the numerous corporate and financial bankruptcies in Japan and Korea since the late 1990s demonstrate. Equally, there has been a widespread regulatory reaction to such events, including the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the US and the Turnbull, Myners and Higgs reviews, whose 1 Enlightenment Economics and IPEG, University of Manchester. I am grateful to the participants in a seminar at the University of Manchester on 22 October 2003 for their comments. All errors and infelicities are my own. Further comments welcome at Diane@enlightenmenteconomics.com Diane Coyle Page 1 3/3/2016 implementation is self-regulatory, alongside new corporate legislation in the UK. In the case of global governance, the sense of crisis dates back earlier to the global financial crisis of late 1997-98 and the failure of the WTO talks in Seattle in December 1999. Initially the debate subsequent to these events was framed in terms of reform of the international financial architecture, but the same debate is now more commonly described in terms of governance: international governance on the one hand; and on the other, good governance within individual countries as an aspect of their potential within the global economy. All international financial institutions and agencies now proclaim their own governance and governance within their member countries to be a priority, and have put considerable institutional efforts and resources into codifying and measuring aspects of good governance. The emphasis on governance has official manifestations ranging from the adoption by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development of a convention outlawing bribery of public officials by businesses to a programme of research on the economic effects of corruption at the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.2 It is harder to pinpoint any particular trigger for the interest in governance in the public sector, but there is nevertheless a vigorous debate on public sector reform in many countries, not just the UK, where improving public services was brought to the fore as a policy priority of the New Labour government elected in 1997. In the United States a prominent commission on public service reform chaired by Paul Volcker reported in January 2003 3, and there is a continuing active state and local level debate on education reform. In France controversy has recently centred on education, with a rapidly increasing proportion of families opting for private schools, and also lately on health given the extraordinary level of excess deaths amongst the elderly during the summer 2003 heatwave. In Germany the government of Gerhard Schröder launched an ambitious programme of reform explicitly calling into question some of the assumptions of the country’s welfare state, under the heading Agenda 2010, in March 2003. In each case the 2 See http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/50/33/1827022.pdf and George Abed and Sanjeev Gupta, Governance, Corruption and Economic Performance, IMF, 23 September 2002, details at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/nft/2002/govern/index.htm 3 Available at http://www.brook.edu/dybdocroot/gs/cps/volcker/volcker_hp.htm Diane Coyle Page 2 3/3/2016 presumption that governments are not matching up to what people want appears to have gained fresh political salience. Of course, perceptions of a crisis as filtered through media reports do not amount to sufficient evidence of the existence of a governance crisis in any of these contexts, even if there are policy adjustments taking place as a result. However, the idea of a crisis of governance, interpreted broadly, is also consistent with widespread polling evidence indicating a loss of public trust in many of the institutions concerned, from big corporations to government agencies and politicians. According to a Mori poll published in April 20034, “while trust in individual professions has generally remained static, trust in institutions has declined, in some cases quite significantly.” There had been significant declines in trust in politicians and government, big companies, the police and the judiciary, journalists and local authorities – but not much decline in trust in professionals such as doctors and teachers according to Mori. Polls in Canada, Britain, the US, Italy, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Ireland have produced similar results. In the United States, the University of Michigan’s index of trust in the federal government has fallen from 52% percent in 1964 to a low of 26% in 1994 before recovering to 34% in 1998.5 A survey (covering 46 countries) by Gallup International (on behalf of the World Economic Forum)6 in late 2002 reported low levels of trust in many institutions, notably governments and politicians, large companies and international organisations such as the WTO. (The armed forces, non-governmental organisations and educators were amongst the most trusted in this survey.) The question is why failures of governance are a hot issue in so many countries and so many contexts at this time (not that there need be one single cause). After all, the range of actors involved is immense – business executives, public officials, international officials, politicians - in a wide http://www.mori.com/pubinfo/rd-trust.shtml http://www.umich.edu/~nes/nesguide/toptable/tab5a_5.htm. The index bounced to 43% in 2002, in common with many similar post-9/11 polls... The National Election Studies index of efficacy shows a more pronounced decline from 74% in 1960 to a low of 33% in 1994, before showing the same pattern of modest recovery then post 9/11 bounce. See http://www.umich.edu/~nes/nesguide/toptable/tab5b_4.htm 6 http://www.weforum.org/pdf/AM_2003/Survey.pdf 4 5 Diane Coyle Page 3 3/3/2016 range of institutions and organisations around the world. It strains credulity to suppose that all of these organisations have become, coincidentally, less well managed since the late 1990s, and more natural to hypothesise that the context in which all organisations are operating has changed in systematically important ways during the past decade or so. My aim is to explore what that systematic change might be. I suggest it is related to the dramatic fall in the costs of processing and communicating information, due to the radical improvements in information and communication technologies. At the most straightforward level, the increased availability of information and greater ease of monitoring institutions must have contributed to the loss of deference noted by so many observers. In other words, it makes it easier to see the warts. Access to information has reduced information asymmetries in many areas of public service; and those where there remain substantial asymmetries such as medicine and education are in many countries exactly the areas where public trust has declined the least (see the poll evidence cited above). At the same time, public expectations of levels of service have increased – this is one of the contributing factors highlighted by the Mori report. In addition, I argue here that the optimal boundaries and internal structures of organisations – whether private or public sector – can be expected to change in response to a reduction in information costs and to any thinning of the information fog in which we all operate. This is a hypothesis which has been raised in the context of the use of ICTs by businesses, and there is a small amount of mainly case study evidence to support it. However, the same argument applies to other kinds of organisation including public sector and international bureaucracies. I. Organisations of all kinds are entities which get to the places markets cannot reach. This includes private sector companies and government department or agencies. Writers from J.M.Keynes to Daniel Bell have recognised the similarities between large organisations in the private and public sectors. Keynes classed certainbig companies as part of the public sector even in a 1924 lecture, well before many of them were nationalised.7 Bell writes: 7 See Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keyes: The Ecconomist as Saviour 1920-37, pp227ff. Diane Coyle Page 4 3/3/2016 “A business corporation, like a university or a government agency or a large hospital – each with its hierarchy and status system – is now a lifetime experience for many of its members. .... if we set up a continuum, with economizing at one end of the scale (in which all aspects of the corporation are single-mindedly reduced to becoming means to the goals of production and profit) and sociologizing at the other (in which workers are guaranteed lifetime jobs and the satisfaction of the workforce becomes the primary levy on resources) then in the last thirty years the corporation has been moving steadily, for almost all its employees, towards the sociolgizing end of the scale.” 8 In economic theory the study of the boundary and form of the firm dates back to the famous essay by Coase9, in which he explained the existence and scope of companies in terms of the costs of transacting in a world of incomplete information. If the transaction costs of market exchange are too high, the transactions will take place within the boundaries of an organisation instead. More recently the New Institutional Economics10 has once again made transactions costs and informational asymmetries central to the theory of the firm (and other types of organization). So when might market transactions be too costly? Most economic theory has concentrated on the impossibility of drawing up complete contracts to cover all contingencies – for example, if a supplier is required to make a costly investment on behalf of a customer but cannot be sure that the customer will not try to renegotiate or walk away if circumstances later change, then vertical integration is likely. However, industries where this situation arises, such as automobile production, display very different structures in different countries, so other forms of transaction cost are also clearly relevant. 8 ‘The Coming of Post-Industrial Society’, (1974), p294. Ronald Coase, ‘The Nature of the Firm’, Economica, 4, November 1937, 386-405. 10 See for example Oliver Williamson, The Economic Institutions of Capitalism (1985) 9 Diane Coyle Page 5 3/3/2016 These could include agency problems, difficulties in transferring complex or tacit knowledge, benefits of detailed market monitoring and so on11. The transactions involved might rely too much on information that is hard to codify and capture in a price. It might be too difficult to monitor effort or compliance because of inadequate or asymmetric information. There might be incompatible incentives or moral hazard. There could be significant externalities or free rider problems. Or the amount and granularity of the information involved might just be too high, leading to prohibitive costs of co-ordination. So organisational structure will vary depending on the nature and size of the transactions costs in each specific context. Thus if detailed local market information becomes more valuable or less costly, greater delegation or even spin-offs might occur. Innovative technologies can also change optimal firm structure. Holmström and Roberts write: “Information and knowledge are at the heart of organizational design, because they result in contractual and incentive problems that challenge both markets and firms. Indeed, information and knowledge have long been understood to be different from goods and assets commonly traded in markets ........ We think that knowledge transfers are a very common driver of mergers and acquisitions and of horizontal expansion of firms generally, particularly at times when new technologies are developing or when learning about new markets, technologies or management systems is occurring.” The typical form of both private and public sector organisations indeed changes dramatically over long periods of time. The half-century after the second world war saw the rise to dominance of the hierarchical, centralised form in large-scale units. Industrial concentration ratios rose in many countries through to the late 1970s. In the private sector this ‘Fordist’ model was associated with increasing concentration due to high capital requirements and economies of scale in the mass market. The same structure was paralleled in the public sector, both in nationalised industries and also in the organizational form of administration and public services. Bengt Holmstrom and John Roberts, ‘The Boundaries of the Firm Revisited’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(4) Fall 1998, 73-94; Kenneth Arrow, ‘Vertical Integration and Communication’, Bell Journal of Economics, 6, 1975, 173-182 11 Diane Coyle Page 6 3/3/2016 Some economists have linked the hierarchical and bureaucratic form to a cluster of early 20th century technologies such as rail, telegraph and electricity which made operations on a large scale both possible and profitable.12 However, the hierarchical, centralised organisation is also a product of high information costs – at least relative to the benefits of transferring knowledge. Hierarchies can minimise communications costs because they minimise the number of links required to connect multiple individuals, compared to more decentralised structures.13 Hub-and-spoke transport networks are analgous. Similarly, standardised products in long production runs offer an efficient way to use an inflexible and scale-intensive manufacturing technology, so greater flexibility thanks to computerisation allows flexible production.14 It is reasonable to expect that lower information costs or higher benefits from the sharing of knowledge because of innovation will lead to an optimal organisational structure that is flatter and more decentralised – exactly the kinds of change that have characterised many private sector companies since around 1990. Best15 identifies an earlier shift away from the classic Fordist model of production to a more complex multi-product ‘just-in-time’ (but still vertically organised) production system pioneered by Toyota, followed by a more recent shift in some US industries to a network model of horizontal inter-firm organisation. He too links this shift to technology transfer: “With open systems the American PC industry has developed a networking model of inter-firm organization that has demonstrated an unprecedented rate of technological innovation and diffusion.”16 In management-speak, these kinds of change towards flatter companies and horizontal organisational forms are variously described as outsourcing, reengineering, delayering and networking. For example, Chandler, The Visible Hand, 1977. See for example Thomas Malone, ‘Modelling Co-ordination in Organizations and Markets’, Management Science, 33(10), 1987, pp1317-1332; and Thomas Malone and John Rockart, ‘Computers, Networks and the Corporation’, Scientific American 265(3), 1991, 128-136. 14 Paul Milgrom and John Roberts, Economic Organization and Management, Prentice Hall 1992. 15 Michael Best, The New Competitive Advantage: The renewal of American Industry, Oxford University Press 2001. 16 Ibid p53 12 13 Diane Coyle Page 7 3/3/2016 There has clearly been less change in the public sector, where the absence of pressure applied by, say, disappointing profits or share prices means organisational change is very much harder to achieve. Nevertheless, the rhetorical themes and patterns of change are similar – decentralisation and devolution have been a common theme in many countries including the UK and France, as has the delegation of authority to separate agencies (such as the outsourcing of interest rate decisions to the Bank of England), and the trimming of some layers of bureaucracy. In the case of the international institutions too there has been an emphasis on delegation and delayering, whether the EU’s principle of subsidiarity or the IMF’s conversion (in principle) to encouraging its borrowers to draw up their own poverty reduction and economic adjustment plans. II. It is worth giving an indication here of the scale of the decline in information and communication costs during the recent past. For the pace of technical progress in ICT, and the consequent decline in costs, is without historical precedent. The figures are simply extraordinary. Moore’s Law is well-known. In 1965 Gordon Moore of Intel predicted the processing power of computer chips would double roughly every two years – later accelerated to every 18 months. The current technological platform of silicon-based semiconductors is predicted to allow Moore’s Law to hold until at least 2015, beyond which horizon new technological platforms are expected to sustain or increase the pace. [FIG 2] The increase in computing power has been so spectacular that it is usually shown on a log-linear scale. Here it is presented on a linear scale to emphasise timing of the exponential ‘take-off’ in computational power, in the late 1990s, as the timing is relevant to the argument here. There has been a correspondingly large decrease in the price of computational power, of the order of 30-40% a year for the past 30 years, or a 99.99%+ decline in three decades. A cent’s worth of computer power today would have cost $10,000 (in today’s money) in 1970. The prices of phone calls and internet connections have been declining at almost equally rapid rates. These numbers are very large, in themselves and by comparison to earlier innovative technologies. For example, the real price of illumination Diane Coyle Page 8 3/3/2016 is estimated to have fallen from 40 cents to 0.1 cent per thousand lumen hours between 1800 and 1990, a modest decline of 99.75% in 190 years (rather than less than 30 years in the case of computers) and by 7-8% a year during the 30 years of peak decline, by comparison.17 Car prices fell 12% a year in real terms during the peak decades of innovation in automobiles from 1900-1930. The bottom line is that the acquisition and exchange of any information that can be codified (in words or pictures) has the potential to become virtually free to almost everybody, almost everywhere. As a result many indicators point to the extremely rapid diffusion of the relevant new technologies since 1995. This is the year in which web browsers becamse commercially available. It also marks the point at which the full exponential power of Moore’s Law took hold, putting cheap and powerful PCs, low-cost phone calls and mobile telephones within reach of very many more pockets. So, for example, the proportion of UK households with internet access at home has climbed from zero in 1994 to 14% in 1999 and 48% on the latest official figures (2003Q2). [FIG 3] Other indicators of rapid diffusion of ICTs include the number of web hosts [FIG 4], and the rising share of ICT investment in GDP [FIG 5]. The rapid diffusion of these technologies has not been confined to the developed countries. Two have made particular strides in the developing world – satellite TV and mobile telephony. The number of mobile subscribers now exceeds the number of fixed telephone line subscribers in about 100 countries. [FIG 6] While in many cases the use of the technology had increased prior to the mid-1990s – and some of the basic technological steps date back to around 1970 – there does in many cases seem to have been a marked acceleration within the past decade. What’s more, the diffusion and use of the technological potential will depend on whether social structures change to accommodate it – after all, about a third of the world’s population still has no access to electricity nearly a century after almost every household and William D. Nordhaus, ‘Do real output and real wage measures capture reality? The history of lightsuggests not,’ Yale University, Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper No. 1078, September 1994. 17 Diane Coyle Page 9 3/3/2016 every workplace in the leading economies was connected to the grid. Institutions matter as well as technological possibilities. III. In this context it is worth asking whether the sense of crisis in governance in such a wide range of institutions could be linked in any way to the new pervasiveness of low-cost information and communication. It is technically and economically feasible for almost anybody in an organisation to acquire and use vast quantities of information – although not necessarily organisationally feasible. For as well as creating internal pressures to reorganise in order to capture efficiency gains, the new technologies also put pressure on organisational forms through their impact on consumers or users. Whether willingly or not, organisations are becoming more transparent. Internal information, and the internal use of external information, have become more readily available to customers or users as well as employees and suppliers. In the case of businesses, the radically reduced cost of processing and communicating information – alongside continuing innovations in manufacturing technology which are reducing the unit cost of short production runs - has created the scope for innovation at ever-finer aggregations of demand for their products and services. In other words greater customisation is leading to an explosion in choice. Most of the product differentiation in the new goods now takes the form of intangible attributes or service-like qualities – these are where value is added. After all, nobody ever said “quantity is the spice of life.” When our basic needs are met, we seek to meet additional wants in individually varied ways. [FIG 7] Henry Ford famously said of the Model T: “The customer can have any colour he wants so long as it’s black.” The choice of new vehicle models in US is now nearly 300; Ford offers 46 colours. The paradigm now isn’t Ford but Dell. Michael Dell says: “Companies that are successful today are those that can get closest to their customers’ needs.” It gives customers ordering online 16 million theoretical possible combinations of specifications for a desktop PC. Diane Coyle Page 10 3/3/2016 Conventional measures of economic welfare such as GDP almost certainly underestimate the welfare benefits of greater choice18. To give a recent example, Brynjolfsson et al19 estimate that the benefits of the increased choice due to online book sales (2.3m titles on amazon.com compared to 250,000 in the Barnes and Noble superstore in New York City) are roughly twice as large as the gains due to reduced book prices. Only the latter effect is conventionally measured as a real income gain, through the deflation of nominal GDP. With only the slow and indirect mechanism of electoral change exerting pressure, it’s no surprise that the public sector is lagging behind leading private sector companies in responding to increasingly fragmented demands or in exploiting the potential of the technologies for efficiency gains. 20 The public sctor is offering services that are considerably more complex than was the case two or three decades ago, so responding to technological potential is not easy. It is not made any easier by the institutional path dependence of public sector organisations – given their history, it is genuinely hard to see how they could move from where they are to where they might optimally be. At the same time, it is hard to see the public sector being able to avoid organisational change when, as private consumers, citizens are experiencing greater choice (including choice over quality) in everything they buy. Public providers of services – especially those which are also provided competitively by private sector organisations, which includes health, education, transportation – are lagging behind in the innovation arms race which is characteristic of modern capitalism. 21 People will most likely not be satisfied with Model T Ford choices in public services when they are increasingly getting Dell or amazon choices in their purchases of private services and products. It is important to stress that this is not an argument in support of the privatisation of public services – it says nothing about the location of the public-private boundary. Nor does it have any implications for the See Nordhaus, cited above. See also Diane Coyle, Paradoxes of Prosperity, chapter one. Brynjolfsson, Erik, Michael D Smith & Yu Hu, ‘Consumer Surplus in the Digital Economy: Estimating the Value of Increased Product Variety at Online Booksellers,’ MIT Working Paper, April 2003, http://ebusiness.mit.edu/erik/CSDE%202003-04-061.pdf 20 I do not want to exaggerate the sharpness of the public-private boundary in drawing this distinciton, however. 21 William J Baumol, The Free Market Innovation Machine, Princeton University Press 2002. 18 19 Diane Coyle Page 11 3/3/2016 universality of public services. It touches, rather, on the organisation of the public sector, the degree of vertical integration in the provision of services and the extent to which users are given choice and control over their experience of public services. To clarify the distinction with an example, I am not arguing that the parental desire for variety means they should have any choice over the school their children attend; on the contrary, there are important social and economic reasons for encouraging more children to attend their local ‘bog standard’ school. But I am arguing that the school system should be reorganised to move away from batch-processing pupils in groups of 25 or 30 in accordance with a standardised curriculum. Instead they should give individual children (and parents) far greater choice over the kinds of options they select within school, over timetabling, over styles of learning, more top-up options outside the school and so on. For my argument is that the contrast between the range of options available in the public and private sectors could be an important source of users’ disappointment with public services. There is obviously no exact parallel in the global context to the pressure of cheap information on organisational form. However, it is reasonable to think that the new availability of information is nevertheless causing tensions and pressures in terms of global governance. “In earlier eras, a culture was transmitted across national boundaries by migration, travel and reading. Since leisure travel and literacy were often limited to the rich, the understanding – and exploitation – of other cultures was often enjoyed only by elites. Television and the post-1970s media, along with cheaper and more rapid transportation via jet airplanes, changed all that. Culture could move with nearly the speed of sound and reach billions of people.”22 Looking at the jump in global access to television from the mid-1990s and mobile telephony from the late 1990s, transmitting to hundreds of millions or billions of people hitherto unavailable information – on any subject from prices in nearby urban markets, practical know-how from networks of overseas migrants through to images of lifestyles to which viewers could not previously have aspired because they didn’t know about them - we should not underestimate the likely impact on culture, politics and business. There is relatively little authoritative research on the social and economic impact on developing countries of television and telephony in particular (as opposed to 22 Walter LaFeber, Michael Jordan and the New Global Capitalism, Norton 2000, p18. Diane Coyle Page 12 3/3/2016 ICT in general, which has generated a far more substantial research literature). However, it seems likely that the impact will be profound. IV These arguments might seem plausible but they raise the obvious question of whether there is in fact any evidence that reduced information costs are changing organisational structures in any significant ways. There have been surprisingly few studies trying to assess this question, even though the theory of the firm rests to a large degree on hypotheses about transactions and information costs, and no research that I am aware of looking at public sector organisations as opposed to businesses. Yet there is some interesting, if patchy, evidence on the corporate front. There have been some case studies, for example, mainly in the US. They suggest that the scope for reorganisation afforded by new technologies has allowed some companies to harness their investments in ICT to raise productivity levels by as much as 25-30%.23 But their experience has demonstrated that improved efficiency is not possible without organisational change. Brynjolfsson and Hitt have argued that the complementary investments in internal organisation, supplier networks and production processes dwarf recorded spending on ICTs.24 They cite many studies which document the substantial changes in work practices needed to make efficient use of the new technologies. Bresnahan, Brynjolfsson and Hitt, surveying about 400 large firms, found that higher IT spending is associated with increased delegation of authority, and a more highly educated and skilled workforce.25 After all, individual employees cannot make use of almost freely available information and flexibility in production if no decision-making authority has been delegated to them. If key decisions still have to be referred up a managerial hierarchy, then the economic benefits of fast access to very fine-grained information (about customer preferences or cost differentials or logistical hiccups, for instance) cannot be realised. See Erik Brynjolfsson and Lorin Hitt(1996 and 2000a) , McKinseys (2001). Erik Brynjolfsson and Lorin Hitt, ‘Beyond Computation: Information Technology and Organisational Transformation’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(4), Fall 2000, 23-48. 25 Timothy Bresnahan, Erik Brynjolfsson and Loren Hitt, ‘IT, Workplace Organisation and the Demand for Skilled Labor: A firm-level analyisis,’ MIT working paper, 2000. 23 24 Diane Coyle Page 13 3/3/2016 In addition to this literature, which explores the impact of ICTs on productivity at the firm level, and reports en passant that productivity gains are linked to the reorganisation of the firm, some studies have looked specifically at the effects of the technologies on firm structure. [Motohashi (2001) reports that firms which have invested more in their computer networks tend to outsource more. More details].26 The results are therefore consistent in finding that the trend in business is towards decentralisation and reduced vertical integration. Another kind of evidence for the incentives to reorganisation offered by the new information technologies is simply the massive mergers and acquisitions boom of the late 1990s [FIG 8]. M&A waves are pro-cyclical but the merger boom of the late 90s clearly swamps the previous boom of the late 80s in magnitude (itself the biggest, relative to relevant GDP measures, to that date). The number of acquisitions in a wide range of US and EU industries, which dominate the global figures, point to a large-scale reorganisation of corporate structures in the leading economies. Another possible indicator is tentative evidence for the polarisation in the size of companies in several countries. We might expect the technologies to hollow out the size distribution of companies. Earlier this paper argued that cheap and pervasive information would encourage local or decentralised decision-making. This would suggest a shift towards smaller sized firms. On the other hand, there are vast economies of scale in many leading industries either because of high fixed capital requirements (autos, aerospace) or high R&D costs (pharmaceuticals, software) or increasingly network effects (software, telecoms) and winner-takes-all effects in demand (cinema, music). Thus there are merits in being very large or in being very small but no compelling advantage in being medium-sized. The size distribution of companies (measured by market capitalisation or number of employees) has in fact been found to follow a power law, with various coefficients. Thus there are few very large companies and more medim sized ones and many more small ones: firm sizes follow a Zipf distribution.27 Thus in the UK, 0.4% of firms have 100 or more employees, 1.7% have 20-99 employees, 8.5% have 5-19, 39.4% 1-4 and 56.2% are sole 26 27 OECD (2003), Hitt (1999), Motohashi (2001). Axtell (1999), Ijiri and Simon (1977). Diane Coyle Page 14 3/3/2016 traders.28 The proportions differ somewhat for other countries but in general the pattern is the same. This pattern occurs in several kinds of economic data, including city sizes, and domestic income distributions. However, in the case of the global income distribution, there is evidence that the power law relation holds only in the middle of the range, between the 30th and 80th centiles, and there are more very rich and very poor countries than implied by a power law. 29 This is equivalent to the now well-known observation that there are ‘convergence clubs’, or in other words that individual countries tend to converge to either a high or low level of GDP per capita.30 There are figures – although not at all comprehensive or decisive suggesting that both very small firms and very large ones are becoming increasingly important, at least in the US and UK economies. Researchers at the OECD, using industry surveys for three benchmark years (1967, 1977 and 90) and five countries, report that the average size of companies by number of employees has fallen sharply in the US and UK and somewhat less dramatically in France and Germany. Only in Japan was there no increase in the employment share of the smallest companies or decrease in the employment share of the largest companies. At the same time, the gap by which average labour productivity of the largest firms exceeds that of the smallest has risen over time. The consequence is that the output shares of the biggest firms have tended to rise over time. 31 In addition, the OECD data set covers establishments rather than enterprises for the US, so cannot distinguish a move to more establishments within one firm from a move towards smaller firm size. Separate research for the US indicates that the average size of firm and the relative importance (in terms of employment or value added) of the largest firms increased during the 1980s and 90s – alongside a decrease in 28 DTI data Di Guilmi et al (2003) 30 Quah (1996), Baumol (1986) 31 Bart van Ark and Erik Monnikhof, ‘Size Distribution of output and employment: a data set for five OECD countries 1960s-1990’, Economics Department Working Paper no 166, OECD1996. 29 Diane Coyle Page 15 3/3/2016 average industry concentration ratios due to a simultaneous rise in the importance of very small firms.32 This evidence hinting that very large companies and very small ones may be becoming more important in their contributions to output, relative to the past, suggests convergence clubs could be developing in this context too. (Axtell’s orginal model explained the decreasing numbers of firms as firm size increases in terms of the increased incentive for individuals within firms to free ride as their own effort becomes less and less important to the firm as a whole. Free riding becomes harder the easier it is to monitor individual effort, which might well occur with a reduction in information costs. So an increase in the relative importance of large firms is consistent with this model, as each individual’s reward could become more sensitive to the individual level of effort. ) To return to the main argument, a further area of relevant evidence for the impact of ICT on firm organisation is a decline in the longevity of companies. Recent technical change could be expected to decrease corporate life expectancy. Value-added is increasingly reliant on intangible assets and investments, such as expenditure on R&D or marketing, brand values, management know-how and employee skills.33 The result is that almost all the increase in real GDP in both the US and UK during the 1990s was ‘weightless’, that is literally involved no increase in the physical mass of economic output.34 As the US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan explained in a recent speech: “A firm is inherently fragile if its value added emanates more from conceptual as distinct from physical assets......Trust and reputation can vanish overnight. A factory cannot.” Thus we might expect a step up in the corporate death rate and decreased average longevity. Long-lived companies have always been rare: of the original 1917 Forbes 100 corporations, 61 had ceased to exist by 1987 and another 21 had fallen out of the list of the 100 biggest US companies. (The 18 survivors included Ford and General Motors, GE, Kodak and DuPont.) But the average company ‘What’s been happening to aggregate concentration in the United States (and should we care?)’, Lawrence J White, Stern Business School working paper, 2001. 33 Diane Coyle, The Weightless World, Capstone 1996/MIT Press 1997. 34 Sheerin, Caroline, ‘UK Material Flow Accounting’, Economic Trends no. 583 June 2002, Office for National Statistics. 32 Diane Coyle Page 16 3/3/2016 lifetime has fallen substantially. In the United States, Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan calculated a time series for the average lifetime of companies listed in the S&P500 index, finding that it moved pro-cyclically (because recessions lead to a higher corporate death rate) but also dsiplayed a strong downward trend from 75 years in 1939 and 25-35 years through the 60s, 70s and 80s to a little over 15 years in 2000.35 Arie de Geus36 calculated that the average life of all EU companies in the mid-1990s (ie including nonlisted small companies) was 12.5 years. Although he did not calculate past life expectancies, this figure for the late 1990s is certainly lower than one might have expected.37 With a lifespan likely to be only 15 years, it is not surprising to find rooted hierarchies vanishing from many private businesses. In the case of governments, it could be argued that reputation based on intangibles is in fact the only relevant source of value. While the issue of longevity does not arise in the case of public sector institutions in modern democracies, the importance of reputational factors in today’s 24-hour media culture could certainly help account for the loss of trust in public bureucracies, both national and international. V. The evidence cited here has covered the corporate sector but a shift in the boundary between the transactions that can and can’t occur in the market, mediated by price, is fundamental to understanding the impact of ICT on organisational form and why this should raise questions of governance across the board. On the one hand, the greater availability of information means more transactions can take place in markets because it is easier to monitor and enforce contracts – hence phenomena such as outsourcing, and the reallocation of production between nations which is at the heart of globalisation. This is a source of tremendous efficiency gains due to the increased scope for specialisation. This raises questions about the boundary but, much more importantly, the form of the public sector. For example, the Bank of England is a state organisation – but need it be? The scope for the exchange of information Foster and Kaplan, Creative Destruction, 2001. De Geus, The Living Company, 1997. 37 Japan may be an exception. Takashi Shimizu reports (2002) that the average coporate life expectancy in Japan is 100 years and has been rising. 35 36 Diane Coyle Page 17 3/3/2016 and monitoring of contract compliance in the case of setting interest rates to meet an inflation target is clear. This is a case where the task could readily be contracted out. In general, where monitoring is relatively straightforward, the public sector could seek efficiencies from more use of outsourcing and a reduced degree of vertical integration. This would also help it offer more choice. To emphasise an earlier point, the issue is not privatisation per se but rather the structure of production of public services. On the other hand, the value of tacit, non-marketable knowledge has been increasing as the economy becomes increasingly weightless. This kind of knowledge is extremely difficult to monitor and difficult to transact in a market. This arguent suggests that big public sector computer systems – which have in many cases been contracted out – should not have been outsourced because monitoring and enforcing contract compliance is impossible. (Equally, private sector companies should not have outsourced this function either. Their experience has often been just as disastrous as the notorious public sector examples.) Intangible value also makes greater demands on the quality of organisations – it raises the returns to organisational capital. The difference in productivity levels between one firm and a competitor may lie almost entirely in their organisational structures and behaviour rather than their spending on ICTs or any physical capital. The failure to reorganise to capture the potential efficiency gains is a failure of governance – in any context, public or private, it is a failure to manage as efficiently as possible. Diane Coyle Page 18 3/3/2016 REFERENCES Abed, George and Sanjeev Gupta, Governance, Corruption and Economic Performance, IMF, 2002, details at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/nft/2002/govern/index.htm Arrow, Kenneth, ‘Vertical Integration and Communication’, Bell Journal of Economics, 6, 1975, 173-182 Axtell, Robert, ‘The Emergence of Firms in a Population of Agents: Local Increasing Returns, Unstable Nash Equilibria and Power Law Size Distributions’, CSED Working Paper No 3, June 1999, available at www.brookings.edu Baumol, William J., ‘Productivity Growth, Convergence and Welfare’, American Economic Review, 76(5), pp 1072-1085, December 1986. Baumol, William J, The Free Market Innovation Machine, Princeton University Press 2002. Bell, Daniel,The Coming of Post-Industrial Society, (1974). Best, Michael, The New Competitive Advantage: The Renewal of American Industry, Oxford University Press 2001. Bresnahan, Timothy , Erik Brynjolfsson and Loren Hitt, ‘IT, Workplace Organisation and the Demand for Skilled Labor: A firm-level analyisis,’ MIT working paper, 2000. Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Lorin Hitt, ‘Paradox Lost? Firm-Level Evidence on the return to Information Systems Spending’, Management Science, 42:4 pp541558, 1997. Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Lorin Hitt, ‘Computing productivity: Are Computers Pulling Their Weight?’ MIT Working Paper 2000. (2000a) Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Lorin Hitt, ‘Beyond Computation: Information Technology and Organisational Transformation’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(4), Fall 2000, 23-48 (2000b). Brynjolfsson, Erik, Michael D Smith & Yu Hu, ‘Consumer Surplus in the Digital Economy: Estimating the Value of Increased Product Variety at Online Booksellers,’ MIT Working Paper, April 2003, http://ebusiness.mit.edu/erik/CSDE%202003-04-061.pdf Chandler, Alfred, The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business, Harvard University Press 1977. Coase, Ronald, ‘The Nature of the Firm’, Economica, 4, November 1937, 386405. Coyle, Diane, The Weightless World, Capstone 1996/MIT Press 1997. Diane Coyle Page 19 3/3/2016 Coyle, Diane, Paradoxes of Prosperity, Texere 2001. De Geus, Arie, The Living Company, Nicholas Brealey, 1997. Di Guilmi, Corraldo, Edoardo Gaffeo and Mauro Gallegati, ‘Power Law Scaling in the World Income Distribution’, Working Paper August 2003, http://www.economicsbulletin.com/2003/volume15/EB-03O40003A.pdf Foster and Kaplan, Creative Destruction, Doubleday, 2001. Hitt, Lorin, ‘Information technology and Firm Boundaries: Evidence from Panel Data’, Information Systems research, 10:9, pp 134-149, June 1999. Holmstrom, Bengt and John Roberts, ‘The Boundaries of the Firm Revisited’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(4) Fall 1998, 73-94. Ijiri, Y, and H.A.Simon, Skew Distributions in the Size of Business Firms, North Holland 1977. Walter LaFeber, Michael Jordan and the New Global Capitalism, Norton 2000. Malone, Thomas, ‘Modelling Co-ordination in Organizations and Markets’, Management Science, 33(10), 1987, pp1317-1332. Malone, Thomas, and John Rockart, ‘Computers, Networks and the Corporation’, Scientific American 265(3), 1991, 128-136. McKinsey Global Institute, US Productivity Growth 1995-1000: Understanding the Impact of Information Technology Relative to Other Factors, October 2001. Milgrom, Paul, and John Roberts, Economic Organization and Management, Prentice Hall 1992. Motohashi, K, ‘Economic Analysis of Information Network Use: Organisational and Productivity Impacts on Japanese Firms’ , METI working paper, 2001. Nordhaus, William D, ‘Do real output and real wage measures capture reality? The history of lightsuggests not,’ Yale University, Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper No. 1078, September 1994. OECD, ICT and Economic Growth: Evidence from OECD Countries, Industries and Firms, 2003 Quah, Danny, ‘Twin peaks: Growth and Convergence in Models of Distribution Dynamics’, Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper no. 280, LSE, February 1996. Sheerin, Caroline, ‘UK Material Flow Accounting’, Economic Trends no. 583 June 2002, Office for National Statistics. Shimizu, Takashi, ‘The Longevity of Japanese Big Business’. Annals of Business Administration Sciences, Vol 1 No 3, October 2002, 39-46) Diane Coyle Page 20 3/3/2016 Simon, Herbert, ‘Organizations and Markets’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol 5, No 2 (Spring 1991), pp25-44. Skidelsky, Robert,John Maynard Keynes: The Ecconomist as Saviour 192037, Macmillan 1992. van Ark, Bart, and Erik Monnikhof, ‘Size Distribution of output and employment: a data set for five OECD countries 1960s-1990’, Economics Department Working Paper no 166, OECD1996. Volcker, Paul, et al, Urgent Business For America: Revitalizing the Federal Government for the 21st Century, available at http://www.brook.edu/dybdocroot/gs/cps/volcker/volcker_hp.htm White, Lawrence J, ‘What’s been happening to aggregate concentration in the United States (and should we care?)’, Stern Business School working paper, 2001. Williamson, Oliver, The Economic Institutions of Capitalism, Free Press 1985. Diane Coyle Page 21 3/3/2016 FIGURE 1 Number of us es of 'governance' in a s ample of newspapers 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Source: Neon database, adjusted to keep sample of newspapers covered unchanged throughout the period. Diane Coyle Page 22 3/3/2016 FIGURE 2 Moore's Law: number of transis tors per integrated circuit, Intel 45000000 40000000 35000000 30000000 25000000 20000000 15000000 10000000 5000000 0 1965 Diane Coyle 1970 1975 1980 Page 23 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 3/3/2016 FIGURE 3 Proportion of UK households with internet access at home 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1998 Diane Coyle 1999 2000 Page 24 2001 2002 2003 3/3/2016 FIGURE 4 Diane Coyle Page 25 3/3/2016 FIGURE 5 Investment in ICT as a share of GDP (%) Source: OECD 2002 5 4 3 1980 2 1990 2001 1 0 Diane Coyle France UK Page 26 US 3/3/2016 FIGURE 6 Global diffusion of technologies tectechnology all figures per 1000 people (UN DP) 20 0 18 0 16 14 0 0 12 0 10 08 0 6 0 4 2 0 00 Diane Coyle TVs Fixed telephone Mobile lin e s s u bs cr ib er s 1970 0 1990 0 1995 5 2000 0 Page 27 2001 1 3/3/2016 FIGURE 7 Number of products available, key supermarket lines Source: Federal Reserve Bank, Dallas Ever-increasing choice... ... number of supermarket products availab Pr o duct 19 80 19 98 Br e ad p ro duc ts 95 324 Bo ttl ed wa ter 12 125 Se as onin gs 61 40 3 Che w in g g um 47 16 7 W a shi ngpo wde r 12 48 Air fre shene r 53 372 Diane Coyle Page 28 le 3/3/2016 FIGURE 8 Global M&A, $ billions Source: UNCTAD, 2003 Diane Coyle Page 29 3/3/2016