Content - University of Warwick

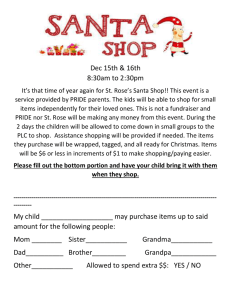

advertisement