The Protestant Death

advertisement

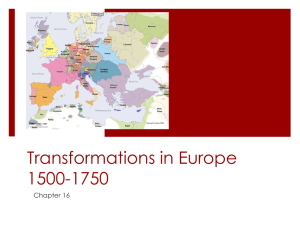

Death in Early Protestant Tradition The living and the dead The relationship between the living and the dead is an important cultural field in every society. In Norwegian society, this relationship has been marked by the Protestant tradition; and this is still largely true today. The main features in the Protestant regulation of this field can be traced back to the sixteenth century, to the Reformation period. And perhaps the most important characteristic of the Reformation changes was a limitation and reduction in comparison to the rules which had governed the relationship between the living and the dead in the late middle ages. In the late middle ages, this field was marked by a mutual relationship in which both the living and the dead had clear roles. According to the Church’s teaching, most of the dead were in purgatory, where they underwent a purification for “venial” sins before they could be welcomed into heaven.1 However, the torments in purgatory could be mitigated and reduced by activity on the part of those left behind on earth – first and foremost, through the Masses offered by the priests for the dead person. One could pay for such Masses for the dead while one was still alive; or else the mourners could purchase them to the benefit of a deceased relative.2 This religious praxis influenced not only the theology and piety of the late middle ages, but also church art and architecture. In many places, the church interior was rebuilt and adapted to a greatly increased number of Masses for the dead. But it was not only those left behind on earth who could help the dead: the dead too helped those left behind. Such services could be performed above all by the saints, those who had been taken directly up to heaven without needing to pass through the extra purification of purgatory. Thanks to their extra merits as saints, they could intercede with Christ for the living – here too, the intention was to mitigate the penalties in purgatory for “venial” sins. Those who did not have the money to pay the priests for Masses for the dead always had access to prayer and the invocation of the saints. All of this field of reciprocal negotiation between the living and the dead – based on a very complex distribution of roles and functions both among the living (priests, laity, the rich and the poor) and among the dead (saints, the dead with “venial” sins, the dead with “mortal” sins) – was dismantled at the Reformation.3 The reciprocal relationship between the living and the dead was replaced by a one-sided relationship in which the dead could still be models for the living through their example, but it was no longer possible for the living to affect the fate of the dead in terms of salvation or damnation.4 The Reformation theology attacked the idea of purgatory and every notion of a calculation where the living and the dead could make up for one another’s deficits on the Only very few died with unexpiated “mortal” sins, so that they went directly to hell; likewise, only very few had no unexpiated “venial” sins, so that they came directly to heaven. On purgatory, cf. Jacques Le Goff, La naissance du Purgatoire, Paris 1981, and Andreas Merkt, Das Fegefeuer. Entstehung und Funktion einer Idee, Darmstadt 2005. 2 The idea behind the celebration of Masses for the dead was that every Mass represented an unbloody repetition of Christ’s sacrifice, and that thereby the Mass too – like the death of Christ – ensured a “plus” on the balance sheet between sin and grace. This “plus” could be converted into a saleable commodity and could benefit anyone at all, provided only that one paid. In the late middle ages, a great number of persons bequeathed their fortunes to the Church to pay for Masses for the dead. 3 Cf. Gilje and Rasmussen, Norsk idéhistorien, Vol. 2, Oslo 2002, 183-202 (the chapter is entitled “The Reformation of death”). See also Bruce Gordon and Peter Marshall, The Place of the Dead. Death and Remembrance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Cambridge 2000; and Craig Kolkofsky, The Reformation of the Dead: Death and Ritual in Early Modern Germany, 1450-1700, London and New York 2000. 4 Cf. Susan Karant Nunn, “‘Gedanken, Herz und Sinn’. Die Unterdrückung der religiösen Emotionen,” in Bernhard Jussen and Craig Koslofsky, eds. Kulturelle Reformation. Sinnformationen im Umbruch 1400-1600 (Veröffentlichungen des Max-Planck-Instituts für Geschichte 145), Göttingen 1999, 87-90. 1 basis of ideas about different types of sin. The consequence was that the entire cultural field which regulated the relationship between the living and the dead underwent severe limitations and a radical concentration. Just as in the late middle ages, it continued to be important in the Protestant culture too to undergo the correct preparation for dying.5 But after a person died, contact with the living was broken off. Everything was now up to God, and human beings had no possibility of exercising influence, no place for negotiation on behalf of the dead person or in his favour. This radical change in the theological field is accompanied in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by a number of changes within the wider cultural field that regulated the relationship between the living and the dead. One central focus is the “staging” of death and of the dead person by means of the funeral and the funerary monument. In the Protestant context, the burial is no longer marked by the Mass for the dead, which was a part of the culture of negotiation between the dead person and the living both in the late middle ages and in confessional Catholicism. Instead, the life and the pious death of the deceased person are to be presented, as far as possible, as an example which will inspire and edify those left behind on earth. Two principal means were employed to make this as clear as possible: the epitaph and the funeral sermon. The epitaph is an upright tombstone which usually includes both picture and text. This type of monument was employed with particular frequency in the Protestant culture in the early modern period, and it certainly appeared to be a suitable means for communicating the Protestant attitude towards death and the dead. One no longer communicated with the dead: instead, a memorial stone was raised above the dead person, and this was intended only to a small degree to communicate individual aspects of this person. It was more important to draw on various aesthetic means to inscribe the dead person in a sacred history, a sacred role. The funeral sermon supplemented the tombstone and had a corresponding rhetorical function. The early Protestant culture for a new type of dealing with dead and the dead did not prevail without opposition and conflict, and this means that it does not always present an unambiguous and consistent appearance. In many ways, thanks to its consistent denial of any possibility of contact with the dead, it could seem very brutal, and the Protestant praxis is not always equally consistent in its “staging” of the new element. The larger problem The main focus of the project is the investigation of the complicated religious and cultural interaction between the old and the new in dealing with death and the dead – with the starting point in Norwegian and Danish source material from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with an emphasis on an interdisciplinary approach, and with emphasis on a European contextualization. The source material consists primarily of two groups: (1) epitaphs and other funerary monuments; (2) funeral sermons, hymns, and liturgy. The European context is constituted primarily by the homeland of Lutheranism, Germany. The specific character of that which is “Protestant” is always investigated in relation to that which is “Catholic,” both as this is displayed in common late mediaeval traditions and as this is displayed in a confessional version from the mid-sixteenth century onwards. Groups of sources and problems which will be investigated in depth 1. Epitaphs and funerary monuments 5 See e.g. Austra Reinis, Reforming the Art of Dying. The Ars Moriendi in the German Reformation (St Andrews Studies in Reformation History), Aldershot 2007; and Tarald Rasmussen, “Hell disarmed? The function of Hell in Reformation Spirituality,” Numen 56 (2009): 366-384. A considerable number of epitaphs have survived in a number of Norwegian churches and Norwegian museums. Taken as a whole, there has been little research into this source material.6 The Norwegian epitaph material has been employed to a very small degree as empirical material in analyses of a broader cultural and religious context. It is characteristic of this situation that the epitaphs are categorized as secular art.7 Although they obviously have links to the emergence of a purely secular portrait painting, the context and the employment of epitaphs are religious, and they are clearly linked to the “staging” of death in Protestant Norway in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This means that the epitaphs constitute a substantial and striking part of the material culture of the Protestant death. The Norwegian epitaphs are related at one and the same time to their Catholic past and to their European present. It is clear that the portraits of persons on the early epitaphs take over the pictorial rhetoric from late mediaeval portraits of donors. In the later epitaphs, where the biblical scenes move into the background or disappear completely, the portraits are strongly influenced by contemporary Dutch painting; at the same time, there is an obvious influence from the Italian Renaissance. This may suggest that the aesthetic choices which are taken in the visual “staging” of the Protestant death do not depend on confessional boundaries. It is also relevant to investigate the extent to which the epitaph culture in Norway was also influenced by the renewal of this genre which took place in the Lutheran heartlands, inter alia thanks to Lucas Cranach.8 The primary goal of this research into the epitaphs is to shed light on their place and function in religious, social, and aesthetic terms in the Lutheran church interior in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with the primary emphasis on Norwegian material. A central element in the interpretation of these sources involves seeing the close connection between image and text, while at the same time emphasizing their function in relation to the larger framework of changed relationships between the living and the dead. Paradoxically, the epitaphs can be regarded both as a continuation of some aspects of the late mediaeval cult of the saints and as a clear breach with this cult. When the Reformation abolished Masses for the dead and the intercession of the saints, the daily dealings with the dead in the churches ceased. But the memorial portraits of persons in authority remained in the churches, and their significance increased greatly. In many churches, they were erected in the places where the pictures of the saints had stood. One can have the impression that the persons in authority who were depicted in the churches inherited the role of the saints as models (exempla virtutis). How are the new models “staged” in the Lutheran epitaphs? What role do biblical figures play as new role models who influence the depiction, 6 To some extent, an overview of the Norwegian epitaph material has been achieved through the registrations by the Fortidsminneforening (Monuments Association) and the work which has gone into Norges Kirker. The topographical archive of the Riksantikvar (Directorate for Cultural Heritage) and the documentation in the collections of various museums are also contributions to a survey. An important instrument for a more precise registration of relevant material is also the so-called “Church building data base” established by the KA (Church employers’ special interest organization). This data base was relaunched in April 2009; Max Ingar Mørk is the consultant with special responsibility for it. The project will have access to this data base in order to make use of it and perhaps also to contribute to its further development with regard to the registration of epitaphs. – To some extent, the epitaph material has been studied from the perspective of the history of art: see e.g. Sigrid Christie, Den lutherske ikonografi i Norge inntil 1800, Vols. 1-2, Oslo 1973, and Våre gravminner under klassisismen, Oslo 1954. A recent Master’s dissertation in the history of art at the University of Bergen examines epitaphs from western Norway: see Gjertrud Eide, Ære, pryd og hukommelse. En empirisk undersøkelse av epitafier fra Vestlandet fra reformasjonen til sent 1600-tall, University of Bergen 2006. For Denmark, cf. Annette Maag, Dyden, døden og drifterne. Billedanalyse over de malede epitafier i danske købstadskirker, Copenhagen 1983. The most extensive investigation of the Swedish material is Peter Gillgren, Gåva och själ. Epitafiemåleriet under stormaktstiden (Ars Suetica 17), Uppsala 1995. 7 Sigrid Christe, in Knut Berg, ed. Norges kunsthistorie, Vol. 3, 23. 8 See Doreen Zerbe, “Memorialkunst im Wandel. Die Ausbildung eines lutherischen Typus des Grab- und Gedächtnismals im 16. Jahrhundert,” in Carola Jäggi and Jörn Staecker, eds. Archäologie der Reformation. Studien zu den Auswirkungen des Konfessionswechsels auf die materielle Kultur (Arbeiten zur Kirchengeschichte 104), Berlin and New York 2007, 117-163. and what place is given to individual traits of the deceased person? Does the new view of death mean that the secular posthumous reputation acquires a different societal significance? – These problems should be studied within the framework of a better interpretation of the organization and iconography of selected church interiors. A thorough knowledge of both the late mediaeval and the Lutheran interpretations of religion is a necessary context for an exact understanding of the epitaphs.9 It is important to investigate how and to what extent the Protestant way of dealing with death and with the dead found expression in the early Lutheran funerary monuments, and it is also necessary to look more closely at the social differences between princes,10 aristocrats, and members of the middle classes – and to see what these differences meant for the form given to their funerals and to their funerary monuments: How does the interplay between social and religious codes look in the context of dealings with death and with the dead? And how does the interplay between gender and religion look in this material? Many of the epitaphs were erected in memory of women, and the rhetoric here is different from the rhetoric in the epitaphs in memory of men. Follow-up in the project The investigation of the epitaph genre will be a central focus in the project. From the perspective of the history of art, post-Doctor Kristin Bliksrud Aavitaland will have a research position financed 50% by the project during its duration, and she will work on the visual “staging” of death in early Lutheranism. In her doctoral dissertation, she investigated the images of death and of the consciousness of death in mediaeval European culture, especially the moral-didactic pictorial genre of the contemptus mundi, and she has pointed out how this genre lives on in the emblematic pictures of the Renaissance and the Baroque which circulated in Europe in apparent independence of confessional boundaries. Her research background in the religious culture of the Middle Ages contributes a necessary and highly relevant competence to the project (see the attached curriculum vitae). In the project, her primary object of study will be the Norwegian epitaph material, especially in the areas around Oslo/Christiania and Bergen, centres where the documentation of the material is most complete. The European context from the perspective of the history of art will be covered primarily by Dr.habil. Kerstin Merkel, currently one of Germany’s most prominent younger researchers in this field. She has recently published her Habilitation dissertation about the funerary monuments to Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, Luther’s Catholic superior.11 She has published a number of essays in the relevant field, and is working at present on a project on “Funeral monuments as a source for research into emotions.” Merkel has agreed to take part in the project, both in conferences and with written contributions. Another very important German participant is Jörn Staecker, professor of mediaeval archaeology at the University of Tübingen. He was one of the editors of the big conference volume Archäologie der Reformation (see n. 8), and has himself done considerable work on the funerary monuments An important contribution by a church historian in this context is Berndt Hamm, “Normierte Erinnerung. Jenseits- und Diesseitsorientierungen in der Memoria des 14. bis 16. Jahrhunderts,” Jahrbuch für biblische Theologie 22 (2007): 197-251. 10 A very recent and important contribution to the interpretation of the tombs of Lutheran princes in the relevant period is: Oliver Meys, Memoria und Bekenntnis. Die Grabdenkmäler evangelischer Landsherren im Heiligen Römischen Reich Deutscher Nation im Zeitalter der Konfessionalisierung, Regensburg 2009. 11 Kerstin Merkel, Jenseitssicherung. Kardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg und seine Grabdenkmäler, Regensburg 2004. Cf. also her recent essay: “Das Bewährte bewahren – Bischof Gabriel von Eyb, Loy Hering und die Grabdenkmäler im Eichstätter Dom,” in Andreas Tacke, ed. Kunst und Konfession. Katholische Auftragswerke im Zeitalter der Glaubensspaltung 1517-1562, Regensburg 2008, 172-190. 9 on Gotland in the early modern period. After taking on his new position in 2008, he has continued to work on funerary monuments from the German area in the early modern period. The project will draw on the strengths of two Danish researchers who have a high level of competence in this field of research. Birgitte Bøggild Johannsen, art director at the National Museum of Denmark, is an expert on Danish funerary culture, especially in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and is one of the editors of the book Danmarks Kirker, with particular responsibility for inventory and funerary monuments. Additionally, Martin Wangsgaard Jürgensen, a researcher at the “Center for the Study of the Cultural Inheritance from Mediaeval Rituals” at the University of Copenhagen, will share in the work by investigating the epitaphs. His background is in the history of art and archaeology, and he is working on a project about interiors and inventory in Lutheran churches after the Reformation. He has also published a number of important works in this field (cf. his curriculum vitae and n. 23). From the perspective of church history, the project leader will investigate the epitaphs as expressions of the Protestant dealings with death and with the dead. He has published studies directly linked to the epitaph tradition, and his present research focuses primarily on German material from Lutheran heartlands in Saxony.12 In many respects, the material from Saxony had a prototypical function in relation to the entire Lutheran area. At the same time, it is marked more thoroughly than the Scandinavian material by the conflict and interplay with the surrounding Catholic milieu. 2. Funeral sermons, hymns, and liturgy Funeral sermons are another genre which underwent a rich development in the late sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries.13 While the epitaphs tended to be more image than text – and with texts which were often nothing more than references to the Bible or brief memorial sentences – the funeral sermons offered the occasion to develop a narrative about the dead person. Is it possible to speak here too of a functional parallelity to the tradition of the saints, in such a way that the funeral addresses – following on from the legends about the saints – contribute the narrative elaboration which is necessary, if a deceased person is to be able to function as a model in practice? In order to investigate such a question in more detail, it would be desirable to identify groups of sources where in some cases both the epitaph and the funeral sermon for the same person have been preserved. Common source material of this kind is found in the case of some German and Danish epitaphs, and preliminary investigations indicate that it will also be possible to establish similar groups of common sources in the Norwegian material too. If the funeral sermon is to be seen in its historical context, it is also important to investigate it in relation to the Lutheran funeral ritual, which in itself is an important object of study in this context. Hymns are a central literary genre for the development of Lutheran religiosity. This genre grew rapidly from the sixteenth century onwards. The hymnals in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were mostly Danish, but several Norwegian hymn writers are known from the seventeenth century. Death is an important subject in the hymn tradition, and it is 12 The emphasis lies on the documentation and investigation of epitaphs and funerary monuments in selected Saxon cities: Freiburg, Zwickau, Meißen, and Pirna. 13 Rudolf Lenz, Eva-Maria Dickhaut, Jael Dörfer et al., eds. Katalog der Leichenpredigten und sonstiger Trauerschriften im Thüringischen Staatsarchiv Altenburg (Marburger Personalschriften-Forschungen 43, Geschichte 14), Frankfurt a.M. 2007, is the most recent volume in a comprehensive series of editions in progress in Germany. In addition to the edition, there is a steady stream of published contributions to research into the funeral sermon genre. See also E. Winkler, Die Leichenpredigt im deutschen Luthertum bis Spener (Forschungen zur Geschichte und Lehre des Protestantismus Vol. 34, R. 10), Munich: Kaiser 1967. obvious that one should draw on hymns too as an important source group in the investigation of the Protestant attitude to death. While the epitaphs and the funeral sermons are first and foremost sources which bear witness to how people related to the dead, the hymns are sources which more directly address death itself, and the relationship between death and life. In his book Master of Death,14 art historian Michael Camille argues that the mediaeval way of thinking saw death as a greater and stronger power than life. Does this apply to the Protestant dealings with death too, such as we find this in the hymns? And to which extent does the hymn tradition from this period reflect and confirm the fundamental religious and theological transformations in the Reformation way of dealing with death which were underlined in the introduction above? Are there also features which point in another direction, suggesting continuity with a mediaeval tradition? This last question is prompted by the universal acknowledgment that popular religiosity is often characterized by a remarkable continuity even in periods when theology and institutional religiosity undergo dramatic changes.15 Follow-up in the project Within the framework of the project, Arne Bugge Amundsen, professor in cultural history at the University of Oslo, will work on the Protestant rituals of death, such as they are reflected above all in the interface between the tradition of funeral sermons and the funeral liturgy – a field of research where he has already published several articles (cf. the curriculum vitae). Here, he will study the “staged,” idealized sequence of actions which is established when one combines the biographical genre of the funeral sermons with the rubrics of the funeral liturgy in order to form a “Christian burial.” From the perspective of church history, the project leader too will work on variations within the Protestant view of death, i.e. on confessional differences between the Lutheran and the Reformed views of death. This will lead on to a study of the Reformed influence in Norway in the periods before and after 1600. Reformed Protestantism has a more rational and anti-aesthetic profile than Lutheran Protestantism, and one important question will be whether such tendencies can be traced also in theological texts about death and the dead in this period. In a wider comparative context, it will also be relevant to investigate the extent to which a genre such as the funeral sermon bears the signs of confessional differentiation in the first half of the seventeenth century, or whether it just as much reflects a functional parallelity across the confessional differences.16 Relevant material from the Danish-Norwegian liturgy and hymn tradition will be studied in detail by Lector Sven Rune Havsteen of the “Center for the Study of the Cultural Inheritance from Mediaeval Rituals” at the University of Copenhagen; hymns from this period are one of his special areas of study. Havsteen will also work on the significance of music for the “staging” of the Lutheran funeral. The international comparative framework in this part of the project will be assured primarily through collaboration with one of Germany’s foremost experts in the history of piety in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period, Professor Berndt Hamm in Erlangen. Edificatory literature connected to death and the preparation of death has been one 14 Yale U.P. 1996. One interesting example is the tradition of mysticism, which constitutes a clear religious continuity through the Reformation, despite the theological and institutional discontinuity. 16 M. Asche and A. Schindling, eds. Dänemark, Norwegen und Schweden im Zeitalter der Reformation und Konfessionalisierung. Nördische Königreiche und Konfession 1500 bis 1600 (Katholisches Leben und Kirchenreform im Zeitalter der Glaubensspaltung 62), Münster: Aschendorff 2003. 15 of his research priorities over a lengthy period,17 and he will participate with his professional competence in the network group. Another comparative view of the Danish-Norwegian material will be contributed by two Swedish scholars. First, Dr. Stina Fallberg-Sundberg, who defended her dissertation in May 2008. This deals with the preparation for death in the Swedish tradition from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period.18 She will be a member of the network group, as will the second Swedish scholar, post-Doctor Otfried Czaika of the Royal Library in Stockholm, who has made an intensive study of the Swedish funeral sermon tradition in the early modern period.19 The project leader is directing the dissertations of four doctoral students who are all working on topics from the late mediaeval/early modern period related to the thematic field of the project; this applies especially to Sivert Angel and Jon Flæten. These students will help form a larger Norwegian research milieu around the project, while at the same time benefiting in their own research from the interdisciplinary working method of the project. The post-doctoral position financed by the project will be linked preferably to the further investigation of the source group funeral sermons/liturgy/hymns, and will be recruited from one of the following academic fields: church history, cultural history, literary science. The aim is that the post-doctoral researcher shall work on Norwegian (and Danish) material from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, where there is a particularly great need for further research. Interdisciplinary approach One essential concern in the project is to establish the kind of interdisciplinary approach in the investigation of the relevant problems which is certainly demanded by the complex source material. In the past, however, the way in which research was organized often failed to facilitate such an approach. In this context, it is very important that traditional textual sources are supplemented not only by iconographical studies of images, but also by studies of the objects which were linked to death and the dead in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In recent years, this has been introduced as an important dimension of the study of religion: scholars have investigated how the material aspects of a religious act, or a combination of authoritative texts, collective acts, and physical objects, help partly to transmit religious patterns and traditions, and partly to create and maintain various forms of social and cultural memory. In this context, many scholars have included bodily experience as an important cultural dimension in religious and ritual praxis.20 In the Norwegian context, this research can be anchored for example in an academic tradition of ethnology and cultural sciences, where the study of “material culture” focuses on the relationship between human goals and results and the intentionality of material objects. Within the framework of such research, the material objects become a representation with many layers of signs and interpretations, where an historical dimension is both necessary and is in fact integral to the very concept of research.21 Applied to religious culture, such Cf. e.g. “Luthers Anleitung zum seligen Sterben vor dem Hintergrund der spätmitteralterlichen Ars moriendi,” Jahrbuch für biblische Theologie 19 (2004): 311-362. 18 Sjukbesök och dödsberedelse: Sockenbudet i svensk medeltida och reformatorisk tradition (Bibliotheca theologiae practicae 84), Uppsala 2008. 19 Cf. most recently his “Die Anfänge der gedruckten Leichenpredigt im schwedischen Reich,” in Wolfgang Sommer, ed. Kommunikationsstrukturen im europäischen Luthertum der Frühen Neuzeit (Die Lutherische Kirche – Geschichte und Gestalten 23), Gütersloh 2005. 20 Catherine Bell, Ritual theory, ritual practice, New York: Oxford University Press 1992. 21 Ragnar Pedersen, Handlingsperspektivet i studiet av meteriell kultur,” Dugnad 17 (1991): 49-62; Idem, “Studying the Materiality of Culture,” Ethnologica Scandinavica 34 (2004): 13-22. 17 perspectives can shed a new light on the “material culture” of Christianity,22 and help illuminate traditional source material in new ways: text, objects, and forms of action shed light on one another. Wider theoretical perspectives linked to European contextualization A fruitful investigation of the Norwegian material sketched above necessarily entails an ongoing study of the European framework within which the Norwegian material is located. Here, there are good reasons for according priority to the Protestant context – and in practice, this means primarily the Danish and the German contexts. The Danish material often constitutes an inseparable proximate context for the Norwegian material in this period. In the broader European context, the most important interpretative framework is the German, and this will be consciously included in the research both with an eye to comparison and with an eye to the investigation of historical relationships of dependence. Material from other European countries, especially Sweden, will be included with the same double goal. – At every point, “the Protestant” also requires a diachronic and synchronous mirroring, both in relation to late mediaeval religiosity and in relation to a confessional Catholicism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. When one works on European contextualization, it is obvious that the entire field of investigation should be viewed in the light of modern theories about the confessionalization of Christianity in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. These theories have been developed above by all German historians from the 1970’s onward,23 and offers a new and challenging frame of reference for the study of European Christianity in the early modern period. One important aim is to investigate the striking structural similarities between the various confessions (Lutheran, Roman Catholic, and Reformed) with regard both to the interpretation of Christianity and to their political and cultural function in society. These similarities form a startling contrast to the religious self-understanding of the confessions, where one central concern for Lutherans, Reformed, and Catholics was to define themselves as much as possible in opposition to the other confessions. This means that the project’s researchers who study the Protestant death must also keep their eyes open to the relationship between the Lutheran development and the development in the two other confessions. Perhaps it will be possible to identify unexpected parallels between the confessions in this area too. Another interesting problem in the work on the Norwegian material in relation to the broader European context is the extent to which the customary interpretation of Norway as a European periphery is appropriate with regard to the overarching theme of the project. Although Norway received strong impulses from countries such as Germany and Italy in the development of a culture for dealing with death and the dead in the early modern period, Denmark-Norway are also distinct in the European context as pure Lutheran areas, with little confessional conflict. This also gives Denmark-Norway a theoretical position as typical Lutheran areas. In a theoretical perspective, this may be just as important as the fact that these two countries constitute a European periphery in a geographical sense. 22 Colleen McDannell, Material Christianity. Religion and popular culture in America, New Haven and London: Yale University Press 1995. 23 SVRG 197 (1986): Heinz Schilling, ed. Die reformierte Konfessionalisierung in Deutschland – das Problem der “Zweiten Reformation”; SVRG 197 (1992): Hans-Christoph Rublack, ed. Die lutherische Konfessionalisierung in Deutschland; SVRG 198 (1995): Wolfgang Reinhard and Heinz Schilling, eds. Die katholische Konfessionalisierung. Cf. also ARG Sonderband (1993): Hans Guggisberg and Gottfried Kobel, eds. Die Reformation in Deutschland und Europa: Interpretationen und Debatten; and SVR 201 (2003): Kaspar von Greyerz, Manfred Jakobuwski-Tiessen, Thomas Kaufmann, and Hartmut Lehmann, eds. Interkonfessionalität – Transkonfessionalität – binnenkonfessionelle Pluralität. Neue Forschungen zur Konfessionalisierungsthese. Relevance In the context of the sixteenth century, the Protestant death represents first and foremost a concentration of the repertoire for the “staging” of death and a limitation of the relationship between the living and the dead. In this way, one can say that it is on a collision course both with Catholic and with Norse traditions, which have likewise left their mark on Norwegian culture. The unsentimental and almost brutal aspects of the way in which the early Lutheran piety dealt with death and with the dead have been continually corrected, challenged, and reshaped after the Reformation, so that in practice the typically Protestant aspects often receded into the background. At the same time, one can affirm that precisely the radical Lutheran endeavors to achieve concentration and limitation in dealing with death and with the dead are relevant in a modern society too: in our culture, there is little place for death and the relationship to the dead. In such a perspective, the Protestant reformation of death in the sixteenth century can be held up as a relevant mirror to our own times, where the transitional points in life are marked by the pressure from varying interpretative traditions in the tension between ritualization, differentiation, and state control of this area.