Night by Elie Wiesel depicts the unimaginable horrors faced by

advertisement

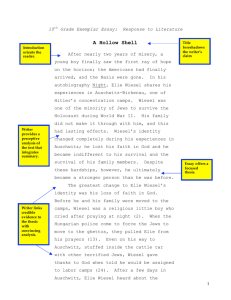

Night by Elie Wiesel depicts the unimaginable horrors faced by those of Jewish descent during the Holocaust. Due to the many atrocities committed during this time, people were tested in both their personal relationships and in their religious beliefs. In Night, Wiesel implies that being exposed to dehumanization causes a person to question his or her faith. This is demonstrated when Elie wonders what kind of God would allow such cruel treatment of human beings, when he defies God on sacred Jewish holidays, and when he reacts to the prisoners’ selfishness in the camps. Elie questions his faith when he witnesses the incredibly cruel treatment of babies upon first arriving at the camp. He reflects on his early moments at Birkenau saying, “Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky...Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever” (Wiesel 40). Seeing babies being burned alive was surreal for the teenage Elie. The dehumanization of innocent people is forever etched into his mind, and he felt himself losing his faith as the people were losing their lives. Similarly, in his essay “Joseph Sungolowsky on Holocaust Biography,” Sungolowsky points out how witnessing such atrocities takes a toll on Wiesel’s once strong faith in God. He states, “the Holocaust causes [Wiesel] to question God’s ways” (Sungolowsky 90). The Holocaust on the whole was an unimaginable tragedy, but witnessing atrocities on a regular basis causes Elie not only to become hopelessly dehumanized, but also to waver in his belief in the almighty. On the other hand, in “Gary Henry on Transcendence in Wiesel’s work,” Henry points out that Wiesel does not lose his faith but in fact has his faith strengthened by what happens to him. He writes, “what Wiesel calls for is a fierce, defiant struggle with the Holocaust, and his work tackles a harder question: how is it not possible to believe in God after what happened?” (Henry 66-67). Henry suggests that in an effort to understand the Holocaust, Wiesel must look to his faith and assume there is a reason for what happened. To carry on, Wiesel must find some purpose in all the madness. Henry’s argument is a compelling one, yet it is clear that Wiesel’s faith is actually shaken in the face of the tragedies of the Holocaust. For instance, during sacred Jewish holidays, Elie rebels against God, proving that his faith has dwindled upon experiencing such horrors.