How new consumers` consumption patterns caused changes in food

advertisement

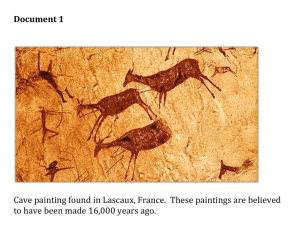

How new consumers’ consumption patterns caused changes in food distribution channels in Croatia Sanda Renko, Faculty of Economics & Business, University of Zagreb1 1 Sanda Renko, PhD, Associate Professor, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Economics & Business Zagreb, J. F. Kennedy 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia, Phone: +385 1 238-3374, fax: +385 1 233-5633 E-mail: srenko@efzg.hr Introduction During the past decade, some trends in food distribution channels became evident in Croatia: the proactive role of modern places of purchase such as supermarkets, and hypermarkets, technological advances, increasing stringent regulations, growing mergers, etc. Reasons for these trends are changes in the sociodemographics of the Croatian population which have led to an increasing demand for convenience foods, ready-to-serve meals and food products in smaller packaging units. Additionally, a significant number of events affecting food market (e.g. Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy – BSE in the meat industry, genetically modified food in the fruit and vegetables industry, etc.) increased consumer concern relating to the place of food purchase and the food purchasing habbits as well. Those new consumers` preferences are especially evident in meat purchasing and meat consumption patterns. In the pre-transition era (prior to 1990), Croatia was the part of Yugoslavia, characterized with the planned economy. Croatian consumers mostly focused on the kinds of meat that were common in the region of their origin. Geographically, Croatia could be divided into three clearly distinguishable regions: Mediterranean, Mountainous and Panonian region. Mediterranean region (Istria and Dalmatia) is the coastal zone on the south, influenced by the Mediterranean climate. Mediterranean region had a tradition of seafish, lamb, goat and poultry consuming. Mountain region (Lika, Banovina, etc.) is the mountain zone that occupies the central part of Croatia and had a tradition of lamb, goat and venison consumption. Due to their windy climate and high temperature oscillations, both regions are familiar with the smoke-drying processing of meat. The third Croatian region, Panonian region, is the main agricultural area and the largest Croatian meat production is made there. There is a widespread practice that involves pig slaughtering, processing, and butchery of pig meat and making ham, bacon, and various sausages. Moreover, this region characterized large-scale poultry production. In that era, channels of fresh meat distribution included: a) small farms which supplied relatives or friends with meat which was cut manually; b) direct sale on open market area; b) local stand-alone butcher shops which co-operate with some farms offering their meat there; c) chains of butcher shops. Processed meat and dried meat snacks were mostly prepared and distributed by butchers in their own stores. Additionally, large meat producers such as Gavrilovic meat industry and Sljeme placed their products on the shelves of supermarkets these days. The period of transition towards a market-oriented economy has caused substantial changes in the meat consumption patterns and distribution channels on the Croatian market. Urban population increased, while small farms population decreased. With the entry of foreign companies, like Western consumers (Veeck, 2010), Croatian consumers have been exposed to an increasingly diverse selection of foods. Those trends affected consumers` preferences and meat consumption patterns as well. Other factors affecting meat purchasing include sociodemographic changes in the Croatian society such as increasing number of working women, longer working-hours, off sets by food consumed away from home, etc. Accordingly, meat producers and retailers induced some changes in their offers. They have become more concerned about health and meat quality, labelling, packaging and about offering more convenience to their consumers. The main goal of the paper is to find out whether new consumption patterns of Croatian consumers affects the way of butchering and choice of the distribution channels in the case of Croatian meat market. The fact is that meat processed products are mainly purchased in supermarkets and hypermerkats, while fresh products are bought in traditional stores and open markets, but in a smaller extent than before. A meat store within a supermarket or a hypermarket is a new concept, widely accepted in the meat distribution on the Croatian market. Regarding slaughtering and butchering, a large portion of animal slaughtering and butchering is still being carried out in small slaughterhouses. The paper begins with the review of the relevant literature to provide a preliminary understanding of consumer choice in relation to channels of distribution. Thereafter, we report the results of a series of focus group interviews which sought to explore issues of channel choice. Based on these and the results of the literature review, conclusive remarks on Croatian consumers’ meat outlet preferences were drawn. Rising consumer income, changing demographics and lifestyles, and shifting preferences due to new information about the links between diet and health all contribute to new demands for foods (Jensen, 2006). Moreover, consumers have experienced the benefits in lower commodity food prices and wider product choice (Manning et al, 2007). Rivera et al. (2010) argue that today`s food service consumers are dramatically different from previous generations because of two-income families, increased discretionary income and lack of time. On the example of American consumers, the same authors (Rivera et al., 2010, p. 21) point out that consumers` fast-paced lifestyle has led to their dramatically changed eating habits where they eat out more than they eat at home, and that their food preferences include prompt service, convenience, brand names, healthy alternatives, variety and high quality. Among various types of food, meat consumption and meat distribution have undergone major changes and have been a much-debated issue in the agricultural economics literature (Becker et al., 2000). Literature review comprised issues such as meat supply chain, consumer perceptions relating to safety and quality of meat, the importance of meat packaging, the impact of some socioeconomic factors on consumers` meat preferences. However, there is a lack of literature and a small number of studies on changes in consumers` purchasing decisions and sales outlet preferences. There is the worth mentioning work of Kizilaslan et al. (2008) who found out that socio-economic factors such as age, household size, place of residence, status of the mother, income, price difference, quality difference, hygiene, freshness and the seller’s image affected the Turkish consumers’ meat outlet preferences. Vignali et al. (2001) focused on consumer purchasing behaviour regarding meat, fish, vegetables and processed food within the Spanish food industry. De Melo et al. (2011) found out relation between lifestyle, attitudes and values of pork and pork products’ consumers and the consumption of these products in Brazil. The objectives of the research of Buzamat et al. (2009) were to evaluate the frequency of meat and meat products consumption in Romania and their preferences for meat types and products. Moreover, this research identified the place where Romanian consumers purchase meat and meat products from. Lakner and Reti (2006) analyzed relationships between the members of the Hungarian meat distribution channel. The consumer behavior literature has addressed the issue of distribution channel choice but often as a more peripheral topic, usually with attention focused on the choice of retail outlet which is then analyzed using conventional models of consumer behavior (Black et al., 2002, p. 161). A common assumption that is made in many writings in the area of distribution is that the choice of channel can be seen in the same conceptual framework as choice of products (Black et al., 2002, p. 162). McEachern and Schroder (2004) have an interesting approach to the area of distribution channels in meat industry. They discussed about reduced consumer confidence in the fresh meat sector and offered value-based labeling communications as the way for reestablishing consumer confidence. The development in the agri-food industry (meat industry presents an important component of the agri-food industry) is lagging behind changes in consumers` life styles and their purchasing habits (McEachern and Seaman, 2005). In order to develop and sustain long-term consumer loyalty, producers and agencies acting on behalf of producers must accurately identify consumer needs, concerns and understanding of the food production environment to ensure future market competitiveness. A fundamental prerequisite of good marketing performance is that of awareness of the customer, and their needs (Leat and Revoredo-Giha, 2008, p. 398). Mousavi et al. (2002) and Quintavalla and Vicini (2002) discuss tools and techniques to improve the production process in handling and cutting meat portions suitable for end users. Clemons and Row (1993) investigated the impact of IT on interactions between manufacturers and retailers in the consumer packaged goods industry. Petrak (2007) argued that we can talk about the evolution of meat packaging and of meat outlets: from carcasses hanging from the hooks in open marketplaces, sides of beef or whole chickens wrapped in white butcher paper, case-ready packages of fresh meat and poultry unloaded and set into retail displays, hot entrees placed into recloseable containers at selfservice bars, to frozen meats sold in zippered, standup pouches and processed meats piled in exact weights into recloseable tubs, sold in every type of store. During numerous studies Grujic et al. (2012) have tried to change the current image of meat and meat products which are not the best for human health. Thus, the improvements that have been made throughout the production chain must continue to obtain a product increasingly healthy, without antibiotic residues, drugs and anabolic steroids and with less fat and cholesterol, nutritionally rich and with high protein value (Bender, 1992). Zaboj (2002) dealt with the problem of choosing the distribution channel for meat production the Czech Republic market and considered four possible distribution alternatives: distribution through own retail selling units; distribution through trans-national retail chains (supermarkets, shopping centres); distribution by using small independent retail units; and distribution through retail units net (retail co-operative). Each of meat distribution alternatives was analyzed related to factors such as: the sale control, the cost of distribution, the affect the final sale price, the number of potential consumers and the affect the cash-flow. The complexity of meat distribution channels was recignized by Leat and Revoredo-Giha (2008) because it includes the breeders and finishers of animals, marketing organisations (including livestock auction markets, where animals are sold on a liveweight basis, and marketing co-operatives, agents and dealers), primary processors (slaughtering, meat-cutting and packing), secondary processors (catering butchers and meat product producers) and distributors (wholesalers, traditional butchers, multiple retailers and food service companies). Although the research focused on the meat distribution channels in Croatia, the analysis of the exiting literature revealed the gap in the literature about consumer meat preferences and meat distribution channels in Croatia. Namely, we can almost conclude that there has been no research interest in the topic of meat distribution channels and consumer preferences in the case of Croatia at all. We found only the work of Gajcevic et al. (2007) who conducted the research on the sample of respondents from the Croatian region Slavonia and concluded that consumers mostly opt for buying and consuming chicken meat produced by domestic producers and that they mostly produce chicken meat in their households. Shopping centers and butcher shops were on the second, and on the third rank respectively. There are some researches about the importance of packaging in meat industry. Bratulic et al. (2012) investigated sustainability of fresh turkey meat packed in modified atmosphere. According to Plazonic et al. (2010) modified atmospheric packaging of meat has been expanded and improved with the arrival of new technologies and increasing demands of buyers. Croatian meat market In Croatia, meat production, distribution and consumption estimations are areas in which the official statistics are the most problematic. Namely, significant portion of the Croatian meat market is involved in „grey market“. Therefore, data presented in this chapter are not completely reliable and should be taken with caution. According to the analysis of Trade Council of Denmark (2007, p. 21), there are three periods of africultural development in Croatia. In the period between mid eighties and mid nineties there was a significant reduction in livestock production, which was followed by the increase in livestock production, especially beef production, since mid nineties. However, global crisis in 2008, affected Croatian meat market as well. Thus, after 2008, significant decrease in meat production appeared. According to data in Table 1, an improvement in the production in 2011 was evident, and it is estimated to grow. - Insert Table 1 - The latest available data, shown in Table 2, show that farms production accounts for the largest portion of meat production (except poultry production). With the approaching the EU, Croatian meat industry is under pressure to comply with the standards of the EU and to modernize its facilities. At the end of 2011, there were 181 companies in the meat and meat processing industry (http://www.jatrgovac.hr , 2012). Few of them transformed themselves from state-run agricultural cominates to private-owned companies. However, the current domestic production of meat satisfies only 50 percent of meat consumption. - Insert Table 2 - Croatians consume most poultry (Table 3) and pork. Per capita consumption figures stand at 18.8kg of poultry, 16.5kg of pork and 9.9kg of cattle per year. Also, there are 15.4kg of processed meat per household member in 2011. Accordingly, annual average per capita meat consumption are 62kg. - Insert Table 3 - Figure 1 clearly suggests that Croatian meat consumption follows meat consumption trends in EU, where meat consumption has been stagnant in the last few years. Comparing the EU meat market and the Croatian meat market, some interesting results were found (Table 4). - Insert Figure 1 - - Insert Table 4 - According to data in Table 4, the average EU consumer spends almost twice as much meat than the Croatian consumer. The difference between them is especially evident in the pork consumption. Channels of meat distribution in Croatia In general, channels of meat distribution in Croatia include: a) direct sale on open market area; b) local stand-alone butcher shops which co-operate with some farms offering their meat there; c) chains of butcher shops; d) supermarkets and hypermarkets; e) the channel of Horeca (hotels, restaurants, snack bars). Nowadays, the harmonization of vertical integration in the meat supply chain (including farms, meat processors, distributors and trade) is the key for gaining competitiveness of the Croatian meat market. Croatian meat producers realized that outputs should be adapted to changed market preferences, such as: - Retailing –requiring convenience, ready to cook meat, strong meat brands, etc., - Butcher shops –preferring large chops and packages, - HoReCa channel members – asking for institutional customers` adjusted offer. There are several very strong meat processing companies with their own network of retail stores and whole distribution centers. Some of the most important Croatian meat producers are “Meat industry Braca Pivac”, “PIK Vrbovec”, “Belje”, “Podravka Danica”. As there is no official data about meat sale per particular distribution channel, only data about the Croatian retail market structure can be given. Table 5 shows the retail market structure related to retail formats, while table 6 gives the insight into top grocery retailers in Croatia. - Insert Table 5 - Supermarkets are leading retail format and they account for 40% of value of grocery retail. Croatian top retailer Konzum accounted for a 9.4 per cent of the Croatian market share in 2002, while it reached almost 30 per cent in 2012 (Croatian Competition Agency, 2012). It operates a variety of formats from convenience stores, supermarkets, hypermarkets and Internet. Its market success is mainly due its central position in the vertical system, where few leading national food producers (such as meat producers “Belje” and “PIK Vrbovec”) are incorporated. It should be pointed out that in order to improve insights into the Croatian meat distribution channels, step-by-step analysis of retail structure per particular Croatian town was conducted. In such a way, only 405 meat stores were found. However, there were some towns with no registered meat store, suggesting that this data cannot represent the Croatian retail meat market. - Insert Table 6 - Methodology The objective of this study is to understand how changing demographics and lifestyles caused changes in meat distribution channels in Croatia. Therefore, given the exploratory nature of the research it was felt that a qualitative approach,using focus group inteviews, was appropriate. Focus groups produce the qualitative data necessarry in an exploratory study, where scientific explanations are desirable and the researcher is uncertain of the nature of the construct to be employed (Black et al., 2002, p. 164). Kennedy et al. (2004) point out that studies of meat have tended to use quantitative methodologies providing a wealth of detailed statistic information, but little in-depth insight into consumer perceptions of meat. In this study six exploratory focus groups were executed from November 2012 to February 2013 in a way that half of them comprised meat distribution channel members (meat producers, the meat-section managers in larger stores as hyper- or supermarkets, the owners of the butcher shop or traditional butchers), and and half of them comprised five to six consumers responsible for meat purchasing within their household. Group participants were recruited on the basis of pre-specified criteria of being derived from three Croatian regions. Consumers involved in the research were selected based on the personal judgement of the interviewer. Finally, research design was organized as follows: Focus group 1. Members of meat distribution channel from the Mediterranean region, Focus group 2. Members of meat distribution channel from the Mountainous region, Focus group 3. Members of meat distribution channel from the Panonian region, Focus group 4. Meat consumers from the Mediterranean region, Focus group 5. Meat consumers from the Mountainous region, Focus group 6. Meat consumers from the Panonian region. Accordingly, two different research instrument were used for this study. Questionnaires for the members of meat distribution channel were adapted from Lakner and Reti (2006) and Leat and Revoredo-Giha (2008) and included strategy of distribution, observations regarding consumers and consumers` preferences, the attituted towards new channels of meat distribution, future expectations concerning Croatia`s acession to the EU, etc. Questionnaires for the meat consumers were adapted from Becker et al. (2000), Kennedy et al. (2004), Resurreccion (2003) and Rimal (2002) and included the frequency of meat consumption in the households, consumers`stated changes in meat consumption and the place of purchase (if any), consumer perceived indicators of meat quality, consumers’ preferences for meat types and products, etc. Using an approach similar to that of Liefeld (2005) and Kemp et al. (2010), we asked participants ‘‘When you were shopping for (item X), what did you consider or take into account?’’ Respondents were probed for more factors (i.e. ‘‘anything else?’’) until their list was exhausted. Each group session lasted on average about 30 minutes and was transcribed verbatim, and thematically content analyzed. Results and discussion Results of the focus group of meat distribution channel In general, discussants` agree that changing demographics, increasing health concerns and restructuring techniques have made an influence on consumers` purchases in recent years. Traditional butcher shop has still a high market share, although some consumers purchase meat from less traditional outlets. There is a growing trend of butcher shop located inside the supermarket/hypermarket. In some case, the point is that local stand-alone butcher shop cooperate with the large retailer. But, in some cases there is the meat department of the retailer. Comparing the data across three regions indicated some differences in strategies of meat distribution. The favoured place of purchase for Mediterranean region is the traditional butcher shop. It provides information about how the meat was produced, and it is regarded as being more convenient. Participants in the first group point out that Mediterranean region foster more traditional values and butchers` shops seem to make a better quality policy. They agree that consumers prefer to have their „own butcher“ who is adding the personal touch in their buyer-seller relationships and to have confidence in them. A butcher from Split (town in the Mediterranean region of Croatia) with more than 20 years experience in meat industry: „My whole family is involved in meat business. I enjoy getting to know all my customers and their meat preferences. They come in, ask me questions, look for some advices and know that they can trust us.“ Similar notions were expressed in the group two. Discussants pointed out that venison (which is very familiar among consumers in the Mountainous region) requires a local butcher. Also, small family farms with the tradition of own meat production are still very important channel of meat distribution. New distribution channels, which include supermarkets or hypermarkets, are not developed equally in this region as in other parts of Croatia. The meat-section manager in a supermarket in Delnice (small town in the Mountainous region of Croatia): „Our offer is very limited because consumers do not use to purchase meat there. Moreover, due to bad weather conditions, in some periods of the year, we have problems with the supply.“ Considerable discussion on the same issue appeared in the group three. With the emergence of large supermarkets and hypermarkets, and changing consumers` lifestyle patterns, small traditional butchers' shops buying the beef from farmers in the local countryside started to loose their market share. They point out restructuring techniques as the new moment in meat industry which influenced the decision about a place of purchase. Restructured meats are prepared using less tender cuts of meat resulting in, for example restructured beef roasts. It provides meat to be served and packaged for convenience to the consumer and to be self served in supermarkets and hypermarkets. Vacuum packaging is also important for the development of new meat distribution channels development. Vacuum packages are easy to handle and to store. However, this region is characterized by large number of small family farms where small production units dominate and which supply relatives or friends with meat which is cut manually. It is interesting that all participants consider Croatia`s accession to the EU (European Union) as the real challenge. They believe that Croatian products are recognized as healthy, nutritious and less dangerous than meat from some other countries like Brasil (one of the largest meat exporters), and that consumers of EU will find Croatian fresh meat as good quality meat derived from healthy animals raised in a healthy environment. Results of the focus group of meat consumers Consistent with the earlier researches (Verbeke and Vackier, 2004), in this study butchers were the preferred supplier of fresh meat, followed by supermarkets. Discussants pointed out that at the time of purchase, traditional butchers shops allow them to judge products on smell and appearance. The fact is that freshness is an indicator for safety in the case of meat, as suggested from the focus group analysis. Consumers agree that they could see the meat better. Some of comments are as follows: „The meat I get at the butcher looks fresher and nicer, and it is possibly better quality.“ „There is a big difference between the meat bought in butcher shop and the meat from supermarkets. You cannot see everything you want at the meat from supermarkets. Supermarkets offer wrapped and packaging meat that are often arranged in a way not to show each side of the meat.“ Debate on the issue about the safety of meat evolved in all three groups, but consumers from the Mediterranean and Mountainous regions were less concerned about the safety of meat. They prefer to purchase fresh meat at their local butchers because they trust their local butchers. They know them for a generations. Also, there were increasing media campaigns about the safety and healthness of the meat. The salient concerns coming out of the focus groups were: antibiotics, BSE (for beef), hormones, salmonella and fat/cholesterol, and respondents mostly believe that they can find the meat with antibiotics on the shelves of some supermarkets/hypermarkets rather than in the butcher shops. Discussants in all groups pointed out that demographics influence the place for purchasing meat. Similar to findings of Kizilaslan et al. (2008) and Vignali et al. (2001), as age descends and work status rises, more respondents prefer hypermarkets. Moreover, as age increases and work status decreases, traditional butcher shops are preferred. When specifically directing the discussion towards consumers’ preferences for meat types and products, and the frequency of meat consumption, respondents agree that they purchase meat not so often and that the majority of meat consumed is red meat. However, poultry consumption has grown rapidly. Respondents in group six pointed out a widespread practice of rural families that involves pig slaughtering, processing, and butchery of pig meat with the final outcomes such as ham, bacon, the sausages. But, for urban families, new channels of distribution (like supermarkets and hypermarkets) have the same importance in consumers` meat supply as local butcher shops. Respondents in all focus groups consider that results could not be generalized due to the fact that consumption patterns and meat preferences of urban consumers differ from those of rural consumers. They suggest to expand the research using the questionnaire conducted on the sample of respondents recruited on the basis of pre-specified criteria: a) to be rural meat consumers and urban meat consumers; b) to originate from diverse Croatian regions. Conclusion This paper investigates the Croatian meat market which has got different tradition of the meat preparation and the processing of meat. The paper focuses on meat distribution channels and changing trends in meat consumption as consumers have less time for home-prepared meals. Relying on the results of the secondary data analysis, it could be concluded that Croatian consumers prefer one-stop shopping and large-scale retailers due to their variety of merchandise offered. At the same time, ready-made meals are not very popular, but it is reasonable to expect that they will also acquire a market due to the increase of urban population and extended working hours. Relying on the results of the qualitative research among consumers and meat distributors in three Croatian regions the study find out that changing demographics, increasing health concerns and restructuring techniques have made an influence on consumers` purchases in recent years. Demographics influence the place for purchasing meat. As age descends and work status rises, more respondents prefer hypermarkets. Moreover, as age increases and work status decreases, traditional butcher shops are preferred. There are also changes in the meat distribution channels, as small traditional butchers' shops buying the beef from farmers in the local countryside started to loose their market share. It is interesting that consumers from the Mediterranean and Mountainous regions were less concerned about the safety of meat as they prefer to purchase fresh meat at their local butchers and they trust them. As meat industry presents the area of strategic importance for Croatian economy (due to its relationships with other industries, such as trade and tourism), the findings of this study can give some directions for improvements to be made in the meat production anddistribution as well. Additionally, as the main limitation of this study lies in the lack of data about the sale obtained via various distribution channels, future researches should conduct more extensive research which could lead to reliable and accurate meat market data. References Becker, T. (2000), Consumer perception of fresh meat quality: a framework for analysis, British Food Journal, vol. 102, no. 3, pp. 158-176. Becker, T., Benner, E. and Glitsch, K. (2000), Consumer perception of freash meat quality in Germany, British Food Journal, Vol. 102, No. 3, pp. 246-266. Bender, A. (1992), Meat and meat products in human nutrition in developing countries, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/t0562e/T0562E00.htm#Contents, accessed 19.01.2013. Black, N. J., Lockett, A., Ennew, C., Winklhofer, H. and McKechnie, S. (2002), Modelling consumer choice of distribution channels: An illustration from financial services, The International Journal of Bank Marketing; vol. 20, no. 4/5, pp. 161-173. Bratulic, M., Cukon, N., Kozacinski, L., Custic, M. and Hafner, S. (2012), Research on sustainability of fresh turkey meat packed in modified atmosphere, Meso, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 259-262. Buzamat, G., Pet, E. and Grigoroiu, E. (2009), Marketing Researches Regarding Meat Consumer’s Behaviour in the Western Part of Country, Bulletin UASVM Horticulture, 66(2), pp. 80-83. Clemons, E.K. and Row, M.C. (1993), Limits to Interfirm Coordination through Information Technology: Results of a Field Study in Consumer Packaged Goods Distribution, Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Summer, 1993), pp. 73-95. Of the Republic of Croatia. Croatian Bureau of Statistics (2012), Statistical yearbook, Zagreb. Croatian Bureau of Statistics (2010), First release, no. 4.2.1/4. De Melo Saab, M.S., Fava Neves, M. and De Barcelos, M.D. (2011), Food Consumer Behavior: a Study about Pork, VIII INTERNATIONAL AGRIBUSINESS PAA-PENSA CONFERENCE – “The Multiple Agro Profiles: How to Balance Economy, Environment and Society, Nov/Dez. 2011, Buenos Aires, Argentina: PENSA. Gajcevic, Z., Kralik, I., Tolusic, Z., Kralik, G. and Tolusic, M. (2007), Consumer`s perception of chicken meat quality, Krmiva, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 103-108. Grujic,R., Grujic, S. and Vujadinovic, D. (2012), Functional Meat Products, Hrana u zdravlju i bolesti, vol. 1, no. 1, pp.44-54. Kemp, K., Insch, A., Holdsworth, D.K. and Knight, J.G. (2010), Food miles: Do UK consumers actually care?, Food Policy, vol. 35, pp. 504–513. Kennedy, O.B., Stewart-Knox, B.J., Mitchell, P.C. and Kizilaslan, H., Goktolga, Z.G. and Kizilaslan, N. (2008), An analysis of the factors affecting the food places where consumers purchase red meat, British Food Journal, Vol. 110, No. 6, pp. 580-594. Lakner, Z. and Reti, A.(2006), Bargaining power, supplier-reseller networks practice: a case study of the hungarian meat distribution system, Society and Economy, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 137–145. Leat, P. and Revoredo-Giha, C. (2008), Building collaborative agri-foodsupply chains: The challenge of relationship development in the Scottish red meat chain, British Food Journal, Vol. 110, No. 4/5, pp. 395-411. Liefeld, J. ( 2005), Consumer knowledge and use of country-of-origin information at the point of purchase, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, vol. 4, pp. 85–96. Manning, L., Baines, R. and Chadd, S. (2008) Benchmarking the poultry meat supply chain, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 148-165 Manning, L., Baines, R. and Chadd, S. (2007),Trends in the global poultry meat supply chain, British Food Journal, Vol. 109, No. 5, pp. 332-342. Manning, L. and Baines, R.N. (2004), Globalisation. A study of the poultry meat supply chain, British Food Journal, Vol. 106, No. 10/11, pp. 819-836. McEachern, M. G. and Seaman, C. (2005), Consumer perceptions of meat production: Enhancing the competetiveness of British agriculture by understanding communication with the consumer, British Food Journal, vol. 107, no. 8, pp. 572- 583. McEachern, M. G. and Schroder, M.J.A. (2004), Integrating the voice of the consumer within the value chain: a focus on value-based labellingcommunications in the fresh-meat sector, Journal of Consumer Marketing, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 497-509. Mousavi, A., Sarhadi, M., Lenk, A. and Fawcett, S. (2002), Tracking and traceability in the meat processing industry: a solution, British Food Journal, vol. 104, no. 1, pp. 7-19. Nielsen Q1 Reports, 2012 Petrak,L. (2007), The future of meat packaging, National Provisioner, Oct., available at: http://www.beefretail.org/CMDocs/BeefRetail/articles/NationalProvisionerTheFutureOfMeat PackagingOct07.pdf, accessed 12.01.2013. Plazonc, S., Miokovic, B. and Njari, B. (2010), Modified atmosphere packaging of meat, Meso: prvi hrvatski časopis o mesu, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 45-48. Quintavalla, S. and Vicini, L. (2002), Antimicrobial food packaging in meat industry, Meat Science, vol. 62, pp. 373-380. Rimal, A.P. (2002), Factors Affecting Meat Preferences Among American Consumers, Family Economics and Nutrition Review, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 36-43. Rivera, D. Jr., Burley, H. and Adams, C. (2010), A Cluster Analysis of Young Adult College Students` Beef Consumption Behavior Using the Constructs of a Proposed Modified Model of Planned Behavior, Journal of Food Products Marketing, vol. 16, no. 1, pp.19-38. Resurreccion, A.V.A. (2003), Sensory aspects of consumer choices for meat and meat products, Meat Science, vol. 66, pp. 11-20. Trade Council of Denmark (2007), Food & retail market in Croatia, Prepared for Landbrugsraadet, Royal Danish Embassy Zagreb. Veeck, A.(2010), Encounters with Extreme Foods:Neophilic/Neophobic Tendencies and Novel Foods, Journal of Food Products Marketing, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 246-260. Verbeke, W. and Vackier, I. (2004), Profile and effects of consumer involvement in fresh meat, Meat Science, no. 67, pp. 159–168. Vignali, C., Gomez, E., Vignali, M. and Vranesevic, T. (2001), The influence of consumer behaviour within the Spanish food retail industry, British Food Journal,vol. 103, no. 7, pp. 460- 478. Zaboj, M. (2002), Choosing the distribution channel for meat products, Zemedelska Ekonomika Agricultural Economics, vol. 48, no.7, pp.327-331. http://www.jatrgovac.hr , accessed 19.09.2012. Table 1 Review of agricultural development (livestock and poultry production, '000) Meat (in kg) 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Cattle Pigs Sheep Poultry 467 1348 646 10053 454 1104 643 10015 447 1250 619 10787 444 1231 630 9470 446 1233 639 9523 Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Statistical yearbook 2012, p. 256. Table 2 Domestic production of meat Meat % produced in companies % produced in family farms Beef Pork Sheep Poultry 24.0 30.9 1.4 75.8 76.0 69.1 98.6 24.2 Source: Trade Council of Denmark, 2007, p. 21. Table 3 Quantities of meat consumed in households (annual average per household member in kg) Meat (in kg) 2009 2010 2011 Beef, veal Pork Mutton, goat, lamb Poultry Game and rabbit Horse meat Edible offal Dried, smoked and salted meat, salami and pate Other preserved or processed meat 11.1 15.8 1.3 18.2 0.4 0.1 0.9 15.7 0.6 10.5 19.8 1.0 19.1 0.3 0.0 1.0 15.4 0.7 9.9 16.5 0.8 18.8 0.3 0.0 0.8 15.4 0.6 Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Statistical yearbook 2012, p. 192. Table 4 Distribution of meat consumption in Croatia and EU (annual average per household member in kg) Meat EU Croatia Index EU/Croatia Beef Pork Sheep Poultry 17.4 42.7 17.2 2.8 9.2 16.2 18.9 1.1 1.9 2.6 0.9 2.5 Total 80.1 45.4 1.8 Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, First release 2010. Table 5 Retail market structure in Croatia Retail format Hypermarkets/supermarkets No. 4,8% Value 55,0% Large groceries 9,7% 21,0% Medium groceries 27,1% 15,0% Small groceries 25,6% 6,0% Kiosks 25,9% 1,0% Gas stations 6,6% 1,0% 13.017 Total number Source: own table according to data in Nielsen Q1 Reports, 2012. Table 6 Top grocery retailers in Croatia (market share, %) Retailer 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Konzum Kaufland Mercator Plodine Lidl Billa 9.4 1.8 1.1 n/a 4.4. 15.1 3.0 3.1 n/a 5.0 19.5 4.8 2.1 1.8 5.0 21.2 5.4 2.4 2.9 6.7 21.5 6.0 4.1 3.9 0.2 7.7 22.6 7.4 5.8 4.2 2.7 6.6 24.3 7.3 5.4 4.6 4.1 5.7 25.8 7.7 5.4 5.3 5.2 Source http://www2.hgk.hr/en/depts/t rade/dist ribut ivna_t rgovina_2010_web.pdf , accessed 20.8.2011 Figure 1 Fluctuation of annual average per household member in kg % Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Statistical yearbook 2012, p. 192.