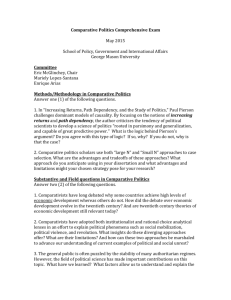

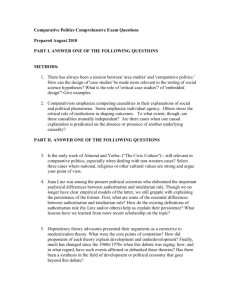

Part IV Comparative Politics

advertisement