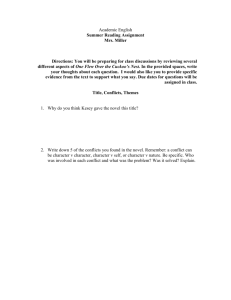

What is Kesey`s overall message in writing this novel

advertisement

Moore 1 Thomas Moore Mrs. Malanka Psychology & Literature 11/9/09 The Four Steps to Freedom In 1962, Ken Kesey published a book called One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Now considered an American classic, the book serves as a commentary on post-war American society. Using a mental institution as his setting, Kesey successfully demonstrates the irrationality of that culture, with its hunger for stability through conformity and intolerance. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was so effective, in fact, that it instigated some Americans to reject the post-war culture of the 1940s and ‘50s. Traces of this culture, though in many ways foreign to contemporary Americans, still have a place in today’s society. And just as Kesey wrote his classic novel with the overall message of rejecting his society, so too have modern artists encouraged their audiences to do the same. K-PAX, a 2001 film based largely on Kesey’s work, is a prime example. In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and K-PAX, the absurdity and futility of a mental institution—and therefore society as a whole—is demonstrated by the sanity of one man perceived to be “crazy.” Kesey and Iain Softley, the director of K-PAX, disparage their societies—the ‘50s and the ‘90s, respectively—in four simple steps. They first prove that their main characters are not insane, despite their present, institutionalized states. In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, McMurphy is transferred from prison time at the Pendleton Work Farm to the hospital in which the plot’s mental institution is located. Although it is never clear if McMurphy chose this relocation or was sent, Kesey makes no pretenses about his sanity. No one, not even the frigid Moore 2 Nurse Ratched, believes that McMurphy truly belongs on the ward. “No,” she says in response to an intern’s assertion that McMurphy be sent to the Disturbed Ward. “He isn’t extraordinary. He is simply a man and no more, and subject to all the fears and all the cowardice and all the timidity that any other man is subject to” (Kesey 136). Prot, the main character in K-PAX, is as mentally sound as McMurphy. In the movie, Prot insists that he is an alien from a distant planet named K-PAX. After two police officers find him at Grand Central Station, Prot is taken to a mental institution where a psychiatrist named Mark Powell tries to “cure” him. Despite the realism pervasive throughout, the movie takes a turn toward science fiction when Powell starts to believe his patient’s stories about K-PAX. Reminiscent of Nurse Ratched (though nowhere as cold), Powell responds to another doctor, “Maybe what’s wrong with [Prot] is that he is…from the planet K-PAX.” Although admittedly not as explicit as McMurphy’s, Prot’s sanity is established early on in the movie. Kesey and Softley’s second step is to use their main characters to show that the other psychiatric patients on the wards are not all that crazy either. Both stories have a climactic scene in which the patients themselves realize their sanity: the boating trip that McMurphy organizes in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and the appearance of a blue jay outside of a window in K-PAX. For McMurphy’s fellow patients, it is a momentous event when they leave the ward for the first time in many medicine-ridden years to go on their boating trip. After their day out on the ocean, the patients learn what “a little bravado and courage could accomplish” (Kesey, 203). They change; no longer the “same bunch of weak-knees from a nuthouse” (Kesey, 215), they realize that freedom is preferable to the stability of the ward. Likewise, the patients on Prot’s ward begin to overcome their obsessions and phobias after he Moore 3 teaches them, as well as the doctors, to find beauty in a common blue jay sitting outside on a tree. Powell is initially angry with Prot for making the other patients think he, Prot, can cure them. Powell says to him, “It is not your job to cure Howie or Ernie or Maria or anyone. It’s mine!” Yet when Prot manages to get the entire ward, including patients who are afraid to leave the building, excited about going outside to see a blue jay, Prot’s therapeutic abilities are apparent. McMurphy also proves more successful at “curing” the patients than Nurse Ratched. This is Softley and Kesey’s third step; having proven the relative sanity of most other patients on the ward, they now establish the absurdity of the mental institutions housing these not so mentally ill. The services provided by these institutions are rendered dispensable by the gained knowledge—of the patients, facilitated by Prot and McMurphy—that freedom, however erratic it may be, is one of the supreme pleasures in life. It is with this goal in mind, the objective of arousing his readers’ desire for freedom, that Kesey (and Softley, following studiously but innovatively in his predecessor’s footsteps) presents One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The inanity of the their respective mental institutions firmly established, Kesey and Softley move on to the critical step in convincing their audiences to reject conformist society. Not only are the institutions absurd, Kesey and Softley contend, but so too are the societies that espouse them. They show their audiences a society in which people, average people like themselves, are deceived into lunacy by their inability to adapt to a perceived standard of normalcy. The audiences are then compelled to pity the patients, who represent themselves, and distrust the hospitals, which represent society (or “the Combine,” in the words of the Chief). As a result, they have only one choice at the Moore 4 conclusion of each text: reject the confines of their societies or be deceived into lunacy as the patients were for so much of their lives.