RhetoricalAnalysis2

advertisement

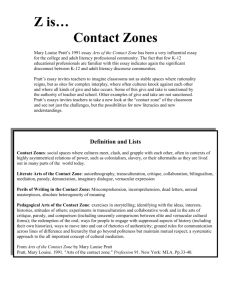

Tyler Shearer Rhetorical Analysis II The essay “Arts of the Contact Zone” is a piece of writing adapted from a lecture given in 1990 by Mary Louise Pratt. The piece focuses on contact between different cultures, and the both beneficial and detrimental outcomes these encounters can result in, which she has dubbed “contact zones.” Her lecture offers the audience a new perspective on contrasting cultures and what these differences can teach them. She effectively demonstrates her points by utilizing personal experiences and clear and concise examples of the contact zone at work. These tools combined with powerful wording make “Arts of the Contact Zone” a very compelling read. Pratt begins by using an anecdote about her son and his love of baseball cards. Through baseball, her son learned about a range of different cultural ideas and the differences these cultures had when compared to his own. In this particular instance, her son's experience with contact zones led to an educational enrichment about ways other people live and his own growth in literacy. It is through this relatable example that Pratt first introduces the audience to contact zones, and allows the reader to look at possible contact zones in their own lives. A second personal experience Pratt relates to the audience is that of her experiences teaching at a university. Due to debate over the requirements of a Western culture course, the class was ultimately made into a much broader defined course known as Cultures, Ideas, Values, and the new class attracted a large amount of students from assorted backgrounds. The differing cultures in the class brought a dynamic contact zone into play when discussing different historical events. Each student had a different cultural background that made each one's perception of things unique. “The lecturer's traditional (imagined) task – unifying the world in the class's eyes by means of a monologue that rings equally coherent, revealing, and true for all... - this task became not only impossible but anomalous and unimaginable,” (p. 496.) When the course no longer had to deliver a lesson that would be universally accepted by the entire class, a culturally rich environment was born where every student experienced a new understanding of history. Her example of a classroom setting contact zone is relatable to her audience, which can be assumed to be mostly students and professors, and this provides a good basis of understanding for what a contact zone is and what it can do. Pratt explains her concept of contact zones further by telling of Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala and his letter to King Philip III of Spain. The twelve hundred page letter, written in 1613 and composed in two languages, Quecha and Spanish, was lost for hundreds of years and never read by its intended recipient. The undelivered letter is an excellent example of a result of the contact zone, and how the blending of cultures in this scenario unfortunately did not end up creating a beneficial outcome. In her telling of this event, Pratt uses a potent variety of words to convey to the audience the essence of a contact zone. She names his letter an “autoethnographic” text, meaning “a text in which people undertake to describe themselves in ways that engage with representations others have made of them,” (p. 487.) She also describes the letter with the word “transculturation,” which “describes processes whereby members of subordinated or marginal groups select and invent from materials transmitted by a dominant or metropolitan culture,” (p. 491.) These words, while most likely unfamiliar to the audience, are a persuasive tool used by Pratt to help the audience understand the instances in which contact zones can occur and why they occur in the first place, especially in a historical setting. The unfamiliarity of the words can cause a disconnect between the audience and Pratt, but due to her extensive definitions and applications of the word, I believe the alienness of them makes them all the more powerful when relaying her ideas about contact zones and causing the audience to really consider them. After finishing this piece, the audience really gains a strong idea of what a contact zone is what they can do for society. Through cultural differences and contact zones, communities can grow and learn from one another, and while sometimes the result of a contact zone may be more negative than positive, the audience gains a better understanding of the importance of embracing contact zones rather than avoiding them. Pratt's relatable experiences paired with a strongly compelling arsenal of impressive word choices make Pratt a highly persuasive speaker and writer, and an effective communicator to her audience.