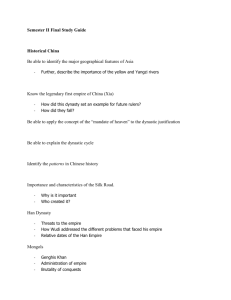

the chapter in perspective

advertisement