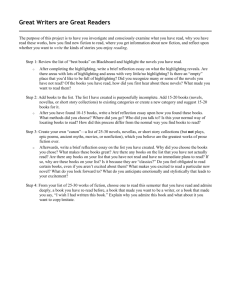

forms of fiction.doc

advertisement

Parascandola 1 Ali Parascandola Daniel Anderson Intro to Fiction July 22, 2010 Forms of Fiction Fiction is a term that applies to many different forms of text aside from novels, referring in literature to work that is not based in reality but rather in imagination. While novels are an effective manner of storytelling, they are only one way among many. All forms of fictitious text generate and discuss specific themes but novels, short stories, graphic novels, and film do so through different methods. Film and graphic novels explain themes in a more visual way, while short stories and novels do so with use of the writing itself. These modes of fictional storytelling fit alongside one another on a spectrum of openness to interpretation, with short stories at the most open end and film as the least open form. As a result of there being great visual and auditory aspects to film, the possible interpretations of a story by an audience are more restricted. Films can tell many different types of stories and can be any length, but successful films all make proper use of cinematography, scenery and costume, character development, and dialogue. Character development in film as compared to other types of fiction is the least flexible, but the integrity of characters is always open to question. Instead of simply describing the setting, films visually show it which requires much less imagination from the audience; however, aspects of the setting can reveal some ideas throughout the story. Color and music, for instance, are often used to signal the mood of the scene and also can give clues about a character’s attributes. For example, in the film adaptation of The Road, color is used to differentiate between joyful flashbacks of the wife and the grim Parascandola 2 reality of life on the road. The music in The Road also adds to the mood of each scene, such as in the house of cannibals when the music works to create a feeling of danger as the “bad guys” come closer. What limits the openness to interpretation of film the most is the filters that the story goes through to become the final product that the audience sees. A director projects his or her interpretation of the story in the directing and actors also give their interpretations of characters in their acting. A film can be compared to the mental picture that a reader imagines while reading a story, however, instead of there being many different possible images available for a scene, there is one. Graphic novels are more open to interpretation than film, but less than textual novels or short stories because the visual imagination that a reader requires to read a strictly textual novel is limited when graphics are added. Graphic novels tell stories by using pictures alongside narrative text. In this way, the setting is shown rather than described, as it is in film. Color plays a role in graphic novels as it does in film, such as in Watchmen where the color of thought and dialogue bubbles changes when Rorschach or Dr. Manhattan is the focus. Color can symbolize characters, as described previously, or the mood. Graphic novels obviously do not have the auditory aspect to them that films have, so music does not play a role in setting the mood. Also, because there is no sound involved in reading a graphic novel, readers do not hear characters’ voices and therefore have more room to interpret them. Interpretation of characters is one of the main differences in the openness to interpretation of films and graphic novels. For instance, in the film adaptation of Watchmen, Rorschach is somewhat defined by his raspy voice that adds to the uncertainty of his integrity. The voice of Dr. Manhattan also adds to his character, as his monotone illuminates his emotional distance from humans. While the graphics of graphic novels leave less character emotion to the imagination of the audience than do textual novels, audiences Parascandola 3 are still able to imagine more than they are in films where these emotions are visibly and audibly acted out. What is shown in graphic novels is only described in textual novels, but this does not necessarily mean there is more or less room for interpretation in either medium, only that there is more room for imagination in textual novels. Novels tell the same type of story as graphic novels: an extended tale that leads up to a concluding event with many meaningful events throughout the story. Characters are given time to develop and have many layers of interpretation to them. Ability for readers to indentify themes in graphic novels versus textual novels is roughly equivalent, as each medium uses different methods aside from the story itself to display the themes. Graphic novels often include details in the images provided to illustrate recurring themes, such as the image of the clock that is evident in Watchmen that symbolizes urgency. Textual novels highlight themes with descriptive imagery, dialogue, and events, such as the cannibalism in The Road that is representative of the destructive tendencies of human nature. Each of these mediums obtains vast openness to interpretation, as the reader is still able to interpret what such images and narrative stands for and what the themes mean. There are many different distinctions between short stories and novels, aside from the obvious fact that short stories are shorter. Along with the length of short stories goes the type of stories that they tell. Short stories typically lead up to a single meaningful event, often with descriptive events recounted earlier in the story. For example, in “A Rose For Emily” the narrator describes the myth surrounding Emily as a result of certain events that happened throughout her life, such as her relationship with Homer and her refusing to pay taxes. However, the entire story leads up to the main event of Emily’s death. In short stories, the deepest meaning is typically held in the details rather than in the plot itself, whereas the details of novels act more Parascandola 4 for description and the plot holds the most meaning. In “A Rose For Emily”, the detail of the long strand of gray hair on the bed at the end of the story is imperative to understanding that Emily had slept with Homer’s corpse long after he’d died. The actual concluding event of the story—Emily’s death—was not the source of meaning, but instead the information that was gathered from the details of that event—the fact she slept with Homer’s corpse—offered meaning to the story. Another important difference between the storytelling of short stories and novels is the types and numbers of themes short stories discuss and how they do so. Novels usually have more complex plots where many different themes are discussed, while short stories focus on one or two main themes that the reader uncovers with more use of their imagination. For instance, in “A Rose For Emily” the main theme could be interpreted as desperation, which is revealed by the gray hair that the reader can infer the meaning of. Short stories often have abrupt endings without explanation, which adds more room for interpretation because the ending is not explained like at the end of a novel. Fiction as a large genre comes in many different forms, such as the forms discussed previously, and can serve many different aims. Fiction can entertain, teach, and challenge ideas depending on the content and form of the work. While novels are a largely utilized form of fiction, the definition of fiction encompasses much more than novels alone and there are limits to the novel as there are with all forms of fiction. Each form of fictitious text has a different historical background, with film being the most recent and technologically advanced outlet for fiction. Fewer people today are reading novels and short stories than ever and more are watching films to be entertained. With society being faster-paced than ever, audiences increasingly want to be entertained rather than use their minds and imaginations to interpret text themselves. As Parascandola 5 technology advances, one has to wonder how fiction will fare and how much imaginative ability audiences will be allowed. McCarthy, Cormac. The Road. New York: Vintage Books, 2006. Print. Gibbons, Dave and Moore, Alan. Watchmen. Toronto: DC Comics, 1995. Print. Faulkner, William. “A Rose for Emily.” The Hudson Book of Fiction. Ed. Sarah Touborg. New York: McGraw Hill Higher Education, 2002. 160-67. Print. “Definition of Fiction.” Brainy Quote. BrainyMedia.com. 2010. Web. 22 July 2010.