The Second Industrial Revolution (1865-1905

advertisement

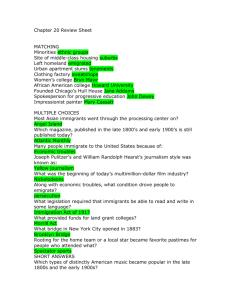

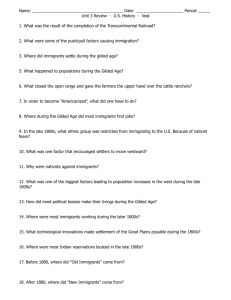

Chapter 15 The Second Industrial Revolution (1865-1905) Section 1 The Age of Invention Industrial Innovations From 1865 to 1905 the United States experienced a surge of industrial growth. These years marked the beginning of a Second Industrial Revolution. This new era of industrial transformation began with numerous discoveries and inventions that significantly altered manufacturing, transportation, and the everyday lives of Americans. The increase availability of steel in the late 1800s resulted in its widespread industrial use. The railroad industry began replacing iron rails with stronger, longer-lasting steel ones. Builders began to use steel in the construction of bridges and buildings. Using steel to create a skeletal frame in buildings allowed architects to design larger, multistory buildings. Like the advances in steel production, the development of a process to refine oil also affected industrial practices. Transportation Innovations in the steel and oil industries led to a surge of advances in the transportation industry. New technology in the late 1800s resulted in a massive expansion of the American railroad network. Entirely new discoveries laid the ground work for air flight and the automobile. These developments in transportation made travel much more efficient and brought Americans into closer contact with each other. Railroads linked isolated regions of the country to the rest of the United States. The growth of railroads had far-reaching consequences. Railroads increased western settlement by making travel affordable and easy. Railroads also stimulated urban growth. Wherever railroads were built, new towns sprang up and existing town grew into major cities. Communications Just as development in transportation made traveling easier and brought people together, innovations in communications technology also brought Americans into closer contact. These advances also furthered the growth of American industry. One of the most significant advances in communications in the 1800s was the telegraph. Samuel F.B. Morse developed the telegraph as a means of communicating over wires with electricity. In March 1876, Alexander Graham Bell developed the “talking telegraph,” or telephone, which had an even greater impact. Christopher Sholes develped the typewriter in 1867. By allowing users to quickly produce easily legible documents, the typewriter revolutionized communications. Other new and useful inventions were developed this time. Section 2 the Rise of Big Business A new Capitalist Spirit The United States operated under an economic system known as capitalism, in which private business run most industries and competition determines how much goods cost and workers are paid. Business leaders shared an American ideal of self-reliant individualism. During this time, many American business leaders attributed their success to their work ethic. A high for self-reliance led many leaders to support the ideal of laissez-faire capitalism. Laissez-faire means “to let people do as they choose.” The theory of laissez-faire capitalism calls for no government intervention in the economy. Most business leaders believed that the economy would prosper if businesses were left free from government regulation and allowed to compete in a free market. This idea is sometimes called free enterprise. In a free-market economy, supply, demand, and profit margin determine what and how many businesses produce. These entrepreneurs argued that any government regulation would only serve to reduce individuals’ prosperity and self-reliance. Some critics of this theory argued that the rapid industrialization of factory life was harmful and unjust to the working class. This view of capitalism was most forcefully argued in mid-1800s by Karl Marx, a German philosopher. Marx proposed a polictical system that would remove the equalities of wealth. He developed a political theory, later called Marxism that called for the overthrow of the capitalist economic system. Marx argued that capitalism allowed the bourgeoisie- the people who own the means of production-to take advantage of the proletariat, or the worker. He also suggested that a new society could be formed on principles of communism. Commuism theory proposes that individual ownership of property should not be allowed. In a communist state, property and the means of production are owned by everyone in the community. The community in turn ideally provides the needs of all the people equally without regard to social rank. American business people also responded to some of the same concerns Marx raised about working class. These business leaders began to embrace the emerging theory of Social Darwinism. Originally proposed by English social philosopher Herbert Spencer, social Darwinism adapted the ideas of Charles Darwin’s biological theory of natural selection and evolution. Social Darwinism argued that society progressed through natural competition. The “fittest” people, business, or nations should and would rise to the position of wealth and power. The “unfit” would fail. Following the law of the “survival of the “fittest,” social Darwinists believed that any attempts to help the poor or less capable actually slowed social progress. Some religious leaders offered religious support for social Darwinism by suggesting that great wealth was a sign of Christian virtue. The Corporation In the late 1800s changes took place in the way businesses were organized. At the close of the Civil War, businesses typically consisted of small companies owned by indivduals, families, or two or more people in a partnership. These traditional business organizations proved unable to mange some of the giant new industries such as oil, railroads, or steel. Nor could these organizations raise the money to found such industries. Business leaders therefore turned to another form of business organization- the corporation. Corporations had existed in one form or another since colonial times. In a corporation, organizers raise money by selling shares of stock, or certificates of ownership, in the company. Stockholders (share holders) – those who buy the shares- receive a percentage of the corporation’s profits, known as dividends. A corporation has serveral advantages over partnerships and family-owned businesses. 1) First, a corporation’s organizers can raise large sums of money by selling stock to many people. 2) Second, unlike small business owners, stockholders enjoy limited liability. In other words, they are not responsible for the corporation’s debt. 3) Finally, a corporation is a stable organization because it is not dependent on a specific owner or owners for its existence. A corporation continues to existes no matter who owns the stock. To run corporations, trusts were formed. In a trust, a group of companies turn control of their stock over a common board of trustes. The trustees then run all of the companies as a singlle enterprise. This pratice limits overproduction and other inefficient business pratices by reducing competition in an industry. If a trust gains exclusive controlof an industry, it holds a monopoly. With little or no competition, a company with a monopoly has almost complete control over the price and quality of a product. Carnnegie and Steel Steel baron Andrew Carnegic understood little about making steel, but he knew how to run an iron business. Carnegic hired the best people in the steel industry and fitted his plants with the most modern machinery. Carnegie’s real success, however, lay in reducing production costs. Canegie realized that by buying supplies in bulk and producing goods in large quantities he could lower production costs and increase profits. This principle is known as economies of scale. To control costs, Carnegie also used vertical integration- that is, he acquired companies that provided the materials and services upon which his enterprises depended. For example, Carnegie purchased iron and coal mines, which provided the raw materials necessary to run his steel mills. He also bought steamship lines and railroads to transport these materials. Because Carnagie controlled businesses at each stage of production, he could sell steel at a much lower price than his competition. In 1899 Carnagie organized all of his companies into the Carnegie steel Company. It dominated the steel industry. Andrew Carnegie also insisted that the rich were morally obligated to mange their wealth in a way that bebefited their fellow citizens. Carnegie donated more than $350 million to charity. Much of his money was used to establish public libraries and other institutions that allowed individuals to improve their lives. Rockefeller and Oil John D. Rockefeller entered the growing oil-refining industry in 1863. Like Carnegie, Rockefeller used vertical integration to make his company more competitive. He acquired barel factories, oil fields, oil-storage facilities, pipelines, and railroads tanker cars. By owning companies that contributed to each stage of oil refining, Rockefeller was able to sell his oil for a cheaper price than his competition. His main method of expansion was called horizontal integration- one company’s control of other companies producing the same product. Standard Oil Company tried to control the oil refineries it could not buy. To drive his competition out of business, Rockefeller made deals with suppliers and transporters to receive cheaper supplies and freight rates. Rockefeller forced most of his rivals to sell out. By 1880 the standard Oil Company controlled some 90% of the country’s petroleum refining capacity. Rockefeller, like Carnegie, gave generously to various charities. He also supported the arts, created a medical insitute, and gave more than $80 million to the University of Chicago. The Railroad Giants Cornelius Vanderbilt was a pioneer of the railroad industry. Vanderbilt invested in railroads and extended his railroad system by purching smaller lines. He then combined them to make direct routes between urban centers. By providing more efficient service, Venderbilt took advantage of the growing demand for rail transportation. Mass Marketing With the rapied growth of manufacturing, companies developed new ways of persuading consumers to puechase their products. Brand names and packaging played important roles in promoting goods. Companies also used advertising to promote their products. In cities, new types of stores that sold a variety of goods were created to cater to the demands of the urban market. Department stores carried a wide variety of products under one roof. Section 3 Labor Strivces to Organize Government and Business The U.S. government’s policies concerning business practices most often bebefited the industrialists, not the workers. Supporters of laissez capitalism claimed to oppose government interference in business activity. However, these same business leaders welcomed government assistance when it helped them. At the same time, the government did little to regulate business pratices, dispite growning pressure form the general public. As Carnegie steel, Standard Oil, and other large corporations grew, many Americans demanded that trust be outlawed. Critics reasoned that without competition, the large monopolies would have no incentive to maintain the quality of their goods or keep prices low. Congress responed in 1890 by passing the Sherman Antitrust Act, which outlaws all monopolies and trusts that restrained trade. The law failed to define what constituted a monopoly or trust and thus proved difficult to enforce. Corporations and trusts continued to grow in size and power. The New Working Class The demand for labor soared under the new industrial order. These jobs were filled largely by the flood of immigrants who came to the United States during the late 1800s. By 1900 about one third of the country’s industrial workers were foreign-born. These immigrant workers were joined by hundreds of thousands of rural Americans who moved to the cities in search of jobs. Amoung this group were thousands of African Americans who moved form the South to the North to find work. Some nothern and midwestern industries offered working opportunities to African American. The vast majority of southern industries, however, barred African Americans from holding factory jobs. Industrial empolyment remained out of reach for most African Americans. The best jobs still went to native-born white workers or to immigrants. Even skilled African American male laborers generally found themselves confined to the dirtiest or most dangerous work or to service-related jobs such as gardening. African American women in nothern cities competed with poor immigrant women for domestic jobs and unskilled factory work. Most women worked because their families needed the income. The number of female workers doubled between 1870 and 1890. By 1900 women accounted for about 18% of the labor force-with some 5 million workers. The number of children in the workforce doubled during this period for the same reason. By 1890 close to 20% of American children between ages 10 and 15- some 1.5 million in all-worked for wages. Across the nation, countless boys and girls worked in garment factories or at home, making clothing or other items by the piece. Others labored in the nation’s canneries, mines, and shoe factories. Working Conditions Children in the labor force often faced terrible conditions. In some textile mills, for instance, children worked 12-hour shifts- often at night-for pennies a day. Low wages and long hours affected all industrial workers, however, regardless of their age, sex, or race. Conditions were particularly difficult for unskilled workers. Most unskilled white male laborers worked at least 10 hours a day, six days a week, for less than $10 a week. Many African American, Asian American, and Mexican American men worked the same number of hours for even lower wages. Futhermore, empolyers made few allowances for women and children, expecting them to work the same number of hours as men for sometimes as little as half the pay. Such long hours left workers exhausted at the end of the day. This fatigue made already unsafe working conditions even more dangerous. Most employers felt no responsibility for work-related deaths and injuries. They made little effort to improve workplace safety. Many workers endured hardships that extended beyound the factory. Some employers sought to increase their control over their workers. They built company towns, where the company owned the workers’ housing and the retail businesses they used. Residents of company towns usually received their wages in scrip. This paper money could be used only to pay rent to the company or to buy goods at company stores. Prices at these stores were usually much higher than at regular stores. Workers often spent entire pay-checks on necessities like food and clothing. The Knights of Labor As conditions grew worse, workers called for change. Knights of Labor: One of the first national labor unions in the United States organized in 1869; after 1879 it included workers of different races, genders, and skills. Terence V. Powderly, its leader, opened the union to both skilled and unskilled laborers. He also welcomed thousands of women into the union’s ranks. Powderly led the Knights of Labor for 14 years. Under his leadership, the union fought for the eight-hour workday, equal pay for equal work, and an end to child labor. The Great Upheaval In 1886 the nation experienced a year of intense strikes and violent labor confrontations that became known at the Great Upheaval. An economic depression in the early 1880s had led to massive wage cuts. Workers demanded relief. When negotiations with management failed, many workers took direct action. By the end of 1886 some 1,500 strikes involving more than 400,000 workers had swept the nation. Many of these strikes turned violent, as angry strikes clashed with aggressive employers and police officers. By the end of the year, worker activism had decreased. Employers began to strike back at the unions. They drew up blacklists- lists of union supporters- that they shared with one another. Blacklisted workers, found it almost impossible to get jobs. Many employers also forced job applicants to sign agreements- called yellow-dog contracts by the workers- promising not to join unions. When these measures failed and workers struk anyway, many companies instituted lockouts. They barred workers from their plants and brought in nonunion strikebreakers. Many of these strikbreakers were African Americans or others who felt abondoned by the unions. As labor suffered repeated defeats, the tide of public sentiment turnes against workers. Union membership shraunk. Alarmed by the violence of the Great Upheaval and by the response of the employers, many skilled workers broke ranks with the unskilled laborers. They joined the American Federation of Labor (AFL), a new union founded by Samuel Gompers in 1886. The AFL organized independent craft unions into group that worked to advance the intrests of skilled workers. Chapter 16 The Transformation of American Society (1865-1910) Section 1 The New Immigrants The Lure of America In the past, millions of immigrants had come to the United States in search of opportunity and a better life. These hopes brought a new wave of immigrants to the United States during the late 1800s. From 1800 to 1880, more than 10 million immigrants came to the United States. Ofthen called old immigrants; most of them were Protestants from northwestern Europe. Then a new wave of immigration swept over the United States. Between 1891 and 1910, some 12 million immigrants arrived on U.S. shores. About 70 percent of these new immigrants were from southern or eastern Europe. Czech, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Russian, and Slovak were amoung the nationalities represented. Most of these new immigrants were catholic, Greek Orthodox, or Jewish. Arabs, Armenians, Chinese, French Canadian, and Japanese also arrived by the thousands. Like the old immigrants, many new immigrants came to the United States to escape poverty, and religious or political perscution. Many immigrants were able to make enough money in the United States to return home and buy land. Others, however, put down roots and stayed. Many immigrants learned of available opportunities from railroad and steamship company promoters. These companies painted a tempting –and often false-picture of the United States as a land of unlimited opportunity. Some railroad companies exaggerated the availability of employment. Steamship lines also charged low fares to attract passengers. Arriving in America Millions of newcomers in the late 1800s first set foot on U.S. soil on Ellis Island in New York Harbor or on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. Both Islands served as immigration stations during this period. Ellis Island opeaned in 1892. Upon arrival, many European immigrants caught their first glimpse of the Statue of Liberty, a symbol of hope for many. All newcomers who passed through Ellis Island were subjected to a physical exam. Those with mental disorders, contagious diseases like tuberculosis, or other serious health problems were deported. Those who passed the physcials entered a maze of crowded aisles where inspectors questioned them about their backgroung, job skills, and relatives. Those with criminal records or without means to support themseleves were sent back. The vast majority were allowed to stay. On Angel Island, thousands of Asian newcomers, who were mostly from China, underwent similar processing. A New Life Many immigrants found life in the United States an improvement on the conditions of their homeland. Nevertheless, the newcomers frequently endured hardship in teir new home. Most immigrants settle in crowded cities where they could find only low-paying, unskilled jobs. As a result, they were generally forced into poor housing located in crowded neighborhoods and slums. Many industrial cities of the Northeast and Midwest became a patchwork of ethnic neighborhoods with numerous pockets of diverse immigrant communities. Neighborhood churches, synagogues, and temples provided community centers that helped immigrants maintain a sense of identity and belonging. They offered day care for children, gymnasiums, reading rooms, sewing classes, social clubs, and training courses for new immigrants. Residents in many cities formed religious and nonreligious aid organizations, known as benevolent societies, to help immigrants in case of sickness, unemployment, and death. The size and number of charitable organizations grew rapidly along with boom in immigration. They attempted to provide an important fuction by helping immigrants obtain education, healthcare, and jobs. Some benevolent societies offered loans to new immigrants to start businesses. Immigrants were often urged by employers, public institutions, and sometimes even family members to join the American mainstream. Mnay older immigrants cherished their ties to the old country. By contrast, their children often adopted American cultural practices and tended to view their parents old- world language and customs as old-fashioned. Whether they adopted American habits or remained tied to the traditions of their homeland; most new immigrants shared a common work experience. Many did the country’s “dirty work.” In constrution, mines, or sweatshops, most immigrants found their work to be difficult and physically exhausting. Hours were long, and wages were low. Some immigrants worked as many as 15 hours a day to earn a living wage. Even the best-paid workers made little more than the minimum necessary to support themselves and their fanilies. The Nativist Response Immigrant workers played an important role in operating the factories that contributed to a strong U.S. economy. Nevertheless, many native-born Americans saw immigration as a threat. Many saw these new comers as too different to fit into American society. Others went further, blaming immigrants for social problems such as crime, poverty, and violence as well as for spreading radical political ideas. Nativists also oppose immigration for economic reasons. Many charged that the immigrant’s willingness to work cheaply robbed native-born Americans of jobs and lowered wages for all. In the West Coast, particularly in California, Chinese laborers found themselves been taken advantage off and persecuted. In 1882 congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which denied citizenship to people born in China and prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers. The Act made conditions worse for Chinese Americans. Immigrant’s endured additional discrimination as new organizations took up the antiimmigration cause. Founded in 1894 by wealty Bostonians, the Immigration Restriction League sought to impose a literacy test on all immigrants. Congress passed such a measure, but President Grover Cleveland vetoed it, calling it “illiberal, narrow, and un-American.” Over the several years congress tried several times without success- to pass a similar measure. Dispite efforts to impose restrictions immigration continued. Contrary to nativists’ arguments, the new immigrants made positive contributions to American society. The rapid industrialization of the United States in the late 1800s would have been impossible without immigrant workers. Section 2 The Urban World The Changing City Before the Second Industrial Revolution, cities were compact. Even in the largest cities, most people lived less than a 45 minute walk from city center. Few builders were taller than three or four stories. By the late 1800s new technological innovations and a flood of immigrants began to transform the urban landscape. Between 1865 and 1900 the percentage of Americans living in cities doubled. In order for urban centers to acconnodate the growing number for residents, architects needed to build skyscrapers, or large, multistory buildings. The height of buildings had previously been limited to some five stories- in part because that was the numbr of flights of stairs that most people could comfortably climb. In 1852 Elisha Otis develped a mechanized elevator, which allowed people and materials to be transported more easily. Architects could then construct buildings well above the five-story limit. The steel frame also relieved the walls from the burden of carring the weight of the building. It allowed buildings to be built to new heights and with more windows and less wall space, devoted to supporting the building. The introduction of the skyscraper transformed city life by concentrating more workers in the central business districts. While skyscrapers extended cities upward, the development of mass transit extended U.S. cities outward. Mass transit included forms of public transportation such as electric commuter trains, subways, and trolly cars. With the development of mass transit, workers no longer had to live within walking distance of jobs or markets. As a result, some urban areas expanded. The expansion of transportation to areas beyond the urban center led to the growth of suburbs- residential neighborhoods on the outskirts of a city. The expansion of streetcar transportation made commuting and, in turn, suburban life more affordable. Upper-Class Life Nouveau Riche: “Newly rich”; new class of American city-dwellers that arose in the late 1800s; most made their fortunes from businesses of the Second Industrial Revolution. Individuals like Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Conelius Vanderbilt- made their money in new industries, such as steel, mining, or railroads. Many members of this nouveau riche class of city-dwellers made an effort to publicly display their wealth. Many of the nouveau rich spent their great wealth freely so that everyone would know how successful they were. Some wealthy people did support social causes. They gave money to art galleries, libraries, and museuns; endowed universities; and established new opera companies, symphony orchestras, and theater groups. Middle Class Life During the late 1800s the growth of new industries brought about an increase in the number of middle-class city dwellers. By the late 1800s the rise of modern corporations had swelled the ranks of the middle class with accountants, clearks, engineers, managers, and salespeople. New industries and a growing urban population created a huge demand for educated workers with a mastery of specialized fields. These fields included education, engineering, law, and medicine. Despite the demand for middle-class professionals, few women were permitted in professional occupations. Nevertheless, rapid urban growth did provide greater opportunities for women to work outside the home. The rise of big business created a variety of new jobs, such as salesclearks, secretaries, and stenographers. Business owners increasingly hired young, single women to fill these positions, paying them lower wages than men. Most married middle-class women worked in the home. Some middle-class families could afford to hire servants to handle many household chores. In such families, women had more free time to focus on their children and to take part in the growing number of cultural events in cities. Many women joined reading and social clubs. Others participated in and led reform movements. How the Poor Lived Although industries and factories offered new opportunties to working class men and women, the ever-growing population of laborers eager to work kept wages low. Living conditions for the working-class city dwellers during the late 1800s were made worse by housing shortage and the rising cost of rent. New York City served as a magnet for hundreds of thousands of immigrants and other migrants. Tenements- poorly built apartment buildings- housed more than 1.6 million poor New Yorkers in 1900-nearly half the city’s population. These rundown buildings were usually clustered in poor neighborhoods. These neighborhoods were typically within walking distance of the factories, ports, and stockyads where many poor city dwellers worked. Outside the crowed tenements, raw sewage and piles of garbage littered unpaved streets and alleys. Worst still, the slums usuallly adjoined industrial areas where factories belched pollution. In such an enviroment, sickness and death were common. Although all residents of poor neighborhoods faced grim conditions, African Americans typically expericenced the greatest difficulties. Because of widespread discrimination, most could get only low-paying jobs. African Americans also had to pay outrageous rents for the most apalling apartments and faced frequent police harrasment. Yet many African Americans perferred life in the North to that in the South. As one African American journalist explained, “they sleep in peace at night; what they earn is paid them, if not they can appeal to courts. They vote without fear of the shot gun, and their children go to school” The Drive for Reform In the late 1800s few government programs existed to help the poor. To confront the problem of urban poverty, some reformers established and lived in settlement houses- community service center-in poor neighborhoods. Settlement houses offered neigborhood residents educational opportunities, skilled training, and cultural events. Jane Addams was at the forefront of the American settlement house movement. Addams began her settlement-house work in 1889. She and Ellen Starr established Hull House, located in a run-down mansion in one of Chicago’s immigrant neighborhoods. Addams founded the settlement house with the ambition of providing social and cultural services to needy Americans. Addams’s central goals were to provide educational and cultural opportunities to the poor and to improve living conditions in the neighborhoods. She also hoped that Hull House would provide fulfilling careers for settlement house volunteers, who were mostly young women. The volunteers who joined Addams were mostly young, college-educated women. They set up a day nursery and kindergarden for the children of working mothers and gave adult-education classes. The experience gained at settlement houses provided the women with the skill and knowledge to make important contributions to social reform and policies. At the same time that the settlement houses began their work, a number of Protestant ministers joined the battle against poverty. They developed the idea of the Social Gospel, which called for people to apply chiristian principles to address social problems. These ministers that the church had a moral duty to confront social injustice. Many churches attempted to act according to the Social Gospel by providing classes, counseling, job training, libraries, and other social services.