VET teachers as change agents for the autonomy of VET

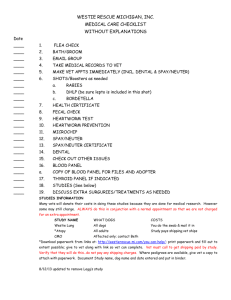

advertisement