Hook, Line, and Sinker

advertisement

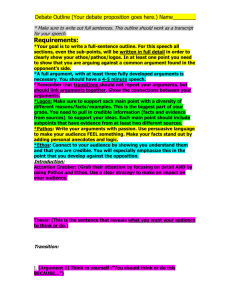

Hook, Line, and Sinker: Writing Effective Papers Introductions In many ways, the introduction is one of the most important parts of a paper. It’s frequently one of the more difficult parts to write. Many of your friends, and perhaps you yourself, have experienced writer’s block, sitting there staring at a blank computer screen with no idea where to begin. It often seems that you have no idea how to fill that much blank space. The minutes tick by with agonizing slowness, but the hours fly by until suddenly it’s nearly time for the paper to be due and you’re still on the first page. The focus of this section will be on writing introductions that are concise and effective. You’ll find that once you’ve mentally laid out your essay in the process of writing the introduction, the rest of it flows rather smoothly and the barriers start to fall away. Of course, all of this presupposes that you have an argument you want to make or something you want to say about this topic. Developing and organizing an argument are addressed below, but that’s not all there is to a paper. Papers are content, yes, but there’s also a matter of presentation. You could have the best argument in the world, but if I can’t tell what it is from your paper then you have a problem. You’ve only got a few lines to hook the reader’s interest, so use them well. Good introductions have four functions. Depending on the length of the paper the introduction is attached to, each can be a sentence, a paragraph, or even a page. We can use a four-part generic introduction template to address everything in a systematic manner, no matter the paper topic you want to insert. Better, once you become comfortable thinking about issues in these terms, you will find that you will have an easier time finding viable paper topics and generating arguments about them. This section will first explore what makes a ‘good’ introduction, then discuss how to formulate good introductions for maximum effect. Finally, I provide several examples of good introductions written using the template described here, and give practice topics for student experimentation. An introduction should do four primary things. 1) It should catch my interest. Obviously, you must have been interested in this topic, or at least this angle on the assigned topic, or you wouldn’t have written on it. Make it catch my interest as well. I should want to read more and see what you have to say about this topic. 2) It should give a reason to want to read it. This is not the same as point 1. When I sit down to grade, I have 50 papers in front of me. Reading 50 repetitions of the same argument is not my ideal way to spend an evening. Why should I want to sit up and pay attention to your argument? Make your argument or angle relevant and/or original-seeming by thinking outside of the box. 3) It should suggest the argument you’re going to make. If I don’t know what you’re going to argue, or what point you’re trying to make, by the end of the first paragraph (first page for papers over about five pages), that’s a very bad sign. 4) It should tell me what to expect in the rest of the paper. No one likes nasty surprises – enough said. Hook, Line, and Sinker: Writing Effective Papers in Political Science 1 Good introductions will do all four of those. Most undergraduate papers in lower-division classes tend to be no longer than 8-10 pages, so the introduction should not normally exceed two paragraphs or a full page. Let’s start, however, with a short paper and thus a shorter introduction. The shortest possible introduction would read something like, This is a problem. It’s an important or interesting problem. Here’s how I think we can solve/explain/understand it. Here’s how I’m going to convince you/explain it. You can substitute ‘quandary,’ ‘anomaly,’ or ‘unexplained or seemingly inexplicable phenomenon’ for ‘problem’ if you like. With that established, let’s walk through what belongs in each part. This is a problem. Here’s something I (or a theory) can’t explain, or that scholars should, in your opinion, be concerned about. At this point you should be stating, clearly, the topic of the paper. If you can, you might put a spin on it that will lead you into phrasing a sentence in the next part as a question. It’s an important or interesting problem. Yes, you can write on cyclical movement trends for the price of beets in Swaziland if you want—provided that you can tell me why I should care about it. This is the ‘so what?’ question. No matter the topic, it’s important to relate it to either a theory or reading that it appears to support (or refute), or some other thing that will convince your reader that it matters. Make your topic relevant to the class. Here’s how I think we can solve/explain/understand it. Political scientists write to make arguments as well as convey information. This sentence serves, approximately, as a thesis statement. It tells me what’s holding your paper together other than ‘this is what the assignment told me to do.’ What’s your take on this question or problem that you’ve brought up? What makes this paper different or distinguishes it from others? In essence, what argument are you going to make in this paper? Here’s how I’m going to convince you/explain it. This part of the introduction is probably the most important to the success of your argument. I often refer to it as a road map or a structure sentence. How will you proceed to discuss this topic? Use the logic of your argument to organize your paper. A wise professor I once had said, “Essays are not mystery stories. I shouldn’t be guessing what’s going to happen next.” A roadmap or structure paragraph or sentence prepares your reader for the logical manner in which you intend to go about supporting your argument. Activity 1. Using the introduction to this section, identify the four parts of an introduction. One major problem that beginning writers face with introductions (and the first sentences of new paragraphs) is an urge to make sweeping generalizations. “From the founding of Rome to the present day, mankind has always known the horror of war. The present war in Iraq will prove to be no less horrific…” Unfortunately, your paper is not about the founding of Rome, the present day, or the horror of war. Your paper is about Bush’s public diplomacy towards Iraq. Stay on topic, and stay focused. Likewise, avoid opening your paper with anyone else’s words but your own. Fight the urge to use the common high school technique of opening with a quotation, or even worse, citing the dictionary. “Webster’s defines cooperation as….” is a sure way to sour the reader’s stomach from the start, as are long digressions on the history of your thinking on the paper topic (“When considering the nature of politics, one must first examine the cultural preconceptions of…”). Hook, Line, and Sinker: Writing Effective Papers in Political Science 2 Some Examples of Introductions A 3-5 page paper on how the faces of power can be used to analyze a current event On January 10, 2003, North Korea withdrew from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Many in the United States interpreted this as a signal that North Korea intended to develop nuclear weapons, and they feared that the cash-strapped country might sell these weapons to other rogue states for hard currency. The United States has since tried to use several forms of power, but particularly persuasion, to defuse this perceived threat to its security. In this essay, I will discuss American attempts to persuade North Korea to rejoin the NPT as well as other uses of rewards, punishment, and force which have been considered. [TYPE 2 THESIS] An 8-10 page paper on comparative political institutions Many democratizing countries have imported governmental institutions from developed democracies, hoping that they could shortcut the institutional development process and shorten the transition period. This approach has met with limited success in several countries: many countries adopting presidential systems, as in the United States, have drifted back into authoritarianism, and a number of new parliamentary systems have suffered severe disruption as parties splintered into factions. This mixed success is particularly noticeable in those countries adopting mixed or hybrid institutions. The semi-presidential systems of government in France and Russia share certain common characteristics, such as the ability to dissolve parliament and the ability to name the prime minister, but particular features of the Russian government, such as the president’s ability to dissolve parliament after three prime ministerial nominations have been rejected, have contributed to Russia’s limited progress toward democratic maturity. This paper will contrast presidential powers in these two countries and discuss their effects on democratic development. [TYPE 3 THESIS] A 5-7 page paper on U.S. foreign aid Many Americans are poorly informed about U.S. foreign aid practices. They consistently overestimate the annual value of humanitarian and development aid, whether in dollar value, percent of GDP, or percent of the federal budget—sometimes by a factor of ten times or more. When asked how much aid they feel is appropriate, survey respondents often name values five times above the current budget (Crossette 1995). Why, then, does Congress persist in being so stingy when voters are so generous? I argue that Congress faces competing pressures on spending. Constituents want more spending on foreign aid, but they also desire more spending on domestic programs which benefit them directly. The U.S. electoral system is designed for individual members of Congress to be accountable to specific constituencies, so Congressmembers prefer to allocate scarce resources to domestic supporters rather than to foreign aid or other international programs. By considering the electoral incentives of the representatives and the constraints those representatives face, we can explain the foreign aid contradiction. [TYPE 4 THESIS] Hook, Line, and Sinker: Writing Effective Papers in Political Science 3 Theses and Thesis Statements The traveling salesmen in the prologue of The Music Man sat around on the train to River City discussing a swindler who often posed as a salesman. “What’s the fella’s line? Never worries ‘bout his line??!! What’s his line?” they asked each other. “Fella’s gotta have a line!” Just like the swindling Professor Harold Hill and the other salesmen on the Iowa Line, you’ve gotta have a ‘line,’ a sales pitch of sorts. Unfortunately, you are not selling anvils, sewing machines, or even boys’ bands; you are selling an idea, and you have to sell it in writing. This means having an argument and drawing it out in the course of your paper. In order to do that, you have to find an argument first. That argument is normally called a thesis. Most instructors in most social science disciplines prefer to see an explicit thesis statement at the front of the paper, which sets out the argument you’re going to make. It is possible to have a thesis without having a thesis statement; it’s also not the easiest type of argument to follow. The reader spends most of the paper wondering how all of these pieces of information and analysis are supposed to fit together, rather than evaluating how well your evidence and analysis support your argument. Social science writing values development of an argument, so for disciplines like political science, it’s best to have the thesis statement up front. The introduction format suggested above includes room for a thesis statement as the third element. Theses matter because they drive the analysis included in a paper. Your thesis is the line that connects all of the pieces of information, and it also shapes how you ‘spin’ the evidence you present. Bland recitations of facts are boring; it’s like reading the news pages of the local paper. The op-ed pages are much more interesting. Read the editorials and letters to the editor sometime. You’ll see examples of authors making arguments, and you’ll also see letters which are little more than barely coherent strings of random facts. Editorials and better-written letters to the editor have a point they want to make, and they’re not shy about making it: you can usually tell right from the start what the author’s view is. Editorials and letters to the editor represent analyses of a situation from a specific point of view. You should aim to have a point of view, a specific angle on the topic—one you can support with evidence. When you have a point of view, or an argument to make, it’s very difficult to write a string of facts. The simple act of having an argument stated at the top of the paper will contribute greatly to having analysis in the rest of the paper. Analysis is interpreting the facts for the reader, discussing the implications or assumptions related to the facts, or similar things that show the reader that you have thought about the facts and are producing original insights about their meaning. The easiest way to do this is to present facts as part of an argument: in other words, using evidence to support your thesis. Crafting arguments for papers is an art. You shouldn’t expect to be doing incredible, amazingly sophisticated analysis as a freshman. Professors have had years of experience crafting arguments, and many of them will be the first to tell you their writing is nothing brilliant or earth-shattering. Instructors understand the progression of writing development and gauge written assignments accordingly. That’s why intro courses often have paper assignments that are a page long, full of specific questions to think about or address, and upper-level classes and graduate courses may only have a line in the syllabus that says, “a 15-20 page researched paper on a topic of your choice, worth x%, due on Week 11.” Developing an argument starts with thinking about the question, either the one your instructor provided or one that you arrived at yourself. The most important thing about your argument, as a beginning writer writing for a specific purpose, is that it should answer the question that is asked, not the one you think is asked. Look at the assignment sheet (or exam sheet). Underline or circle the key words in the question that tell you specifically what the instructor is looking for in the essay. Look at the example below. What specific item or items is the instructor looking for in grading this essay? Hook, Line, and Sinker: Writing Effective Papers in Political Science 4 Question: What roles do power, preferences, and perceptions play in international bargaining? Use a historical example to illustrate your argument. Students saw: What roles do power, preferences, and perceptions play in international bargaining? Use a historical example to illustrate your argument. Instructor looking for: What roles do power, preferences, and perceptions play in international bargaining? Use a historical example to illustrate your argument. These exam essays were all full of theses about how of power, preferences, and perceptions interacted in an example. Some of those arguments were quite good. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the question. When instructors grade, they look for specific elements, ideas, or items that they felt were required for a solid answer to the question that was asked. Even if you have a wonderful essay, if you don’t have those things the professor felt you needed to answer the question asked on the exam, you get a low grade. If you aren’t sure you’re thinking about the right question, or want to try your argument out on someone first, go talk to the instructor. Office hours can be very lonely if no one comes to visit. (In an exam, raise your hand!) Once you’ve figured out what the question is, consider angles to approach it. What constraints are there on the format? Is this a compare-contrast paper, or some other specific format or structure? How much space do you have to make your argument? Are there specific sub-questions the instructor asks you to address? Do any of the readings address this question or closely related questions? These questions prepare you to create a thesis that is both well-developed as well as feasible for the paper length. Then it’s time to brainstorm. Sometimes you’ll have an idea for an argument right off. For most of us, this is a rarity. These immediate theses are sometimes an intuitive leap between readings or random facts, or sometimes they are reactions to statements from instructors or readings or things in the news. If you are not lucky enough to have a thesis spring fully developed from your subconscious, join the club. Here are some approaches to developing a thesis: Flip through your notes or the course texts, looking for references to key words from the assignment. See which ones occur together, and what else occurs frequently around them. How do those words fit together? Write key words or important terms on index cards, then rearrange the cards until you can tell a story that connects them. Similarly, try making an idea web. Put the central concept in the center of a sheet of paper. Around it, write major words that are closely related to it, and connect them to the core—and to each other if appropriate. Think of other things that could be spoked off your mid-level words, and look for connections across and around the entire web. Make a table. Put key words at the top of the columns, then brainstorm related words and concepts into the column space below. Look for patterns, interesting connections, or other concepts related to the assignment. Do preliminary research. Collect some data (information), then look for patterns in it. Consider the course readings you’ve had on this topic or related ones. Do you agree with them? Do they agree with each other? Do the arguments they present seem to apply well to other cases or examples you know? (Yes or no responses to the last question can generate excellent papers.) Longer papers: If you have a general topic you’d like to address, look at literature reviews for that topic. Short literature reviews can be found in related journal articles (scholarly research reports), and sometimes journals publish longer, article-length literature reviews. These present summaries of other authors’ arguments and approaches. You might find one you agree (or disagree) with, or one that you think could be applied to your case or topic. Hook, Line, and Sinker: Writing Effective Papers in Political Science 5 Specificity and Complexity No matter what they taught you in high school, simply rephrasing the question is not a good way to create a thesis. Or rather, it will give you a thesis, but a very weak one that will not support much analysis. Look at the course essay below, and compare the four theses listed below it. Question: Discuss the writings of Chalmers Johnson and Max Weber as revolutionary theorists. 1: The writings of Max Weber and Chalmers Johnson can be considered revolutionary theory. 2: Chalmers Johnson and Max Weber can both be classified as revolutionary writers, though their work focuses on different aspects of revolution. 3: Both Johnson and Weber see revolution as a feature of society as a whole, rather than as an individual phenomenon or one with distinct leaders and followers. 4: Max Weber and Chalmers Johnson have common views on the role of dissatisfaction in creating a revolution, but their conceptions of revolution itself are contradictory. These theses are in increasing order of difficulty. Can you see why? Each successive thesis calls for additional knowledge and information. Thesis 1 is what I call a “Look what I found!” thesis, one that simply says you found evidence of what the question asked. Hopefully, instructors won’t assign paper topics for which absolutely no evidence exists, so this kind of a thesis is possible for all papers and therefore isn’t particularly original. I could substitute a variety of names in for “Chalmers Johnson” and “Max Weber” and still have a true statement. Thesis 2 is getting a little more specific: I can’t necessarily substitute just any pair of revolutionary theorists in for the names of Johnson and Weber. Theses 3 and 4 are both quite focused: there are very few other names I could insert and still have a true sentence. Thesis 3 identifies specific elements that you have identified as being part of their shared heritage. Thesis 3 is broader than thesis 4, though, and has more ‘wiggle room.’ Thesis 4 gives very specific information and allows the author to provide a much more detailed and nuanced answer to the prompt in the same amount of space that the other authors used. To write on Thesis 4, your introduction has most likely established the groundwork, and you can begin your argument immediately rather than waiting for several stage-setting paragraphs. Once you have a thesis, take a moment to make an outline. Write your thesis statement at the top of the page. Highlight key words in it, and then number them in some logical order that supports your argument. Call those your “Roman numeral” outline elements, and write each on a separate sheet of paper. Under each, think about what “capital letter” elements you need to make your point. You may know Max Weber’s birthday and astrological sign, but are those really needed? For the question here and thesis 1, we would first need to define revolutionary theory, then discuss those of Weber’s works and those of Johnson’s works which fit into this category. Those are our three Roman numeral sections; capital letter elements for the last two would be names of books or essays by each which can be considered ‘revolutionary theory.’ Number elements under each of those titles would probably be some brief summary of the item and then a note about which parts of your definition that title meets. You might find that the order the words occur in your thesis statement doesn’t make the most logical argument as you develop the outline; don’t be afraid to rearrange and reorganize until you find something you’re comfortable with. Better to re-write an outline now than have to re-write whole paragraphs if you change your mind later. A Thesis 1 paper developed in the manner suggested above would not be a bad paper. It would meet the minimum standard for the essay, and unless it was factually inaccurate and incoherent, I would Hook, Line, and Sinker: Writing Effective Papers in Political Science 6 probably give it a C or C+. This is what I expect every student can do. A paper that tackled Theses 3 or 4, though, shows me that the student has more than a passing knowledge of the theorists and a more indepth understanding of what revolutionary theory involves. Theses 3 or 4 allow the student to add his or her own interpretation to the arguments by placing them in specific contexts. This additional analysis brings the paper up to the B+/A- range, or even the A range for exceptional essays. Activity 2. Draft outlines for theses 2, 3, and 4 using the framework above. (Hint: You don’t need to know anything about either writer!) More on Arguments I encourage students to think outside the box when they look for arguments. Do you have knowledge from another class that might be useful for this paper? Perhaps you’ve never studied the Russian policymaking process before, but are there theories about the American policy process that you might be able to try in the Russian context? Does this topic remind you of something else, or suggest a comparison or contrast? I wrote a take-home midterm as a sophomore comparing the progress of European integration to the plot of the movie Evita. (Don’t ask.) While I don’t think I’d encourage you to go that far, consider where you’ve heard these terms before, or what other course material might be relevant. Do not insult your reader’s intelligence. Be sure that your paper is arguing something rather than just presenting facts. In other words, “Tell me something I don’t already know.” If I can find your thesis statement in the textbook or other readings, I have to wonder how much of the ‘analysis’ is your own original work. Reach out, think about it, and take a risk with your argument. Probably most important with thesis development, and paper writing in general, is that you use the instructor as a resource. Remember, this is the person who is grading the paper! Unless the instructions specifically prohibit it, I recommend consulting with the instructor at least once on every major paper you write. The instructor knows the course material. He or she can help you think through the question, generate possible theses, consider possible counterarguments, or suggest references or other sources you might want to consult. Instructors are particularly good at helping students take a theme or topic of interest and turn it into an appropriate thesis. However, the instructor will not write the paper for you. You should come to office hours or an appointment with some type of brainstorm, idea list, rough outline, etc., which can serve as the basis for a productive discussion. I cannot stress enough the importance of consulting with the instructor. Especially if you are concerned your topic/thesis may not be appropriate, consultation is an invaluable step. If this is the first time you have written a paper of this style, type, or field, you may want to ask the instructor about conventions in this field. If you are new to the social sciences, this particularly applies to you. One of my students in my first term teaching was an engineering major. The paper assignment was to summarize and critique a scholarly article. This student wrote an excellent paper—in the format of a lab report. The thesis was at the end as a conclusion or finding, all the parts of the article were presented in order (“The author first discusses…. He next considers…”), there was very little citation or critique, etc. What would otherwise have been a B+ type of paper ended up in the C- range because conventions (specified in advance on the rubric) were not followed and the paper generally did not fill the assignment goals and requirements. Hook, Line, and Sinker: Writing Effective Papers in Political Science 7 Conclusions Whoever said, “it’s not where you start, it’s where you finish”? If you did it right, you finish at the same place you started. You return to the puzzle, problem, or quandary you started with, the one that formed the central question your paper tried to answer. But what else goes there? It’s easier to start with what doesn’t go there. The conclusion is not the place for new information. If you find yourself wanting or needing to put a citation in your conclusion, you should reconsider if that information really goes there, or if it perhaps could do better somewhere else. Likewise, editorializing is a bad plan, anywhere in the paper, unless you are specifically asked to do so. Several good strategies exist for a conclusion. For short papers, I tend to prefer a strong reiteration of the argument. Remind the reader about the kinds of evidence you’ve presented and how it relates to your thesis. Does your thesis say anything about other closely related cases, or does it speak to broader questions or arguments in the literature? Keep it short and to the point, sticking closely to your initial argument. For longer papers, or ones where I got to develop my own topic and argument, I often find that I like to discuss implications or extensions of my argument. Can this argument say anything about any other cases I didn’t specifically discuss? Is it likely to do so, or is it a thesis fairly specific to the case(s) under consideration? Can it help us predict any future occurrences, events, or behaviors? Are there other applications of this argument, perhaps in a more generalized form? I also like to think about what other kinds of evidence might exist for this argument (or similar ones). What would I need to look for to show more convincingly that my argument is right (or wrong)? When writing on a topic that was provided, depending on the thesis I used, I sometimes discuss weaknesses in the argument or in the theory it’s based on, or suggest other questions that need to be studied and answered. Are there any cases or theories that contradict the argument or evidence I’ve presented? Does the argument I’ve made seem to apply to the real world? Above all, be sure that your conclusion has made some effort to answer the biggest question of all: SO WHAT? At the beginning of the paper, you made some type of statement about why this is an important problem/question/quandary/etc., and you proposed a solution or way of thinking about the problem. Does your solution/analytical device help? Can it explain this case/topic/controversy, and/or other ones? Your reader should have some feeling that there was a ‘point’ to the paper other than fulfilling the assignment. The reader should have a sense that there was a specific, focused argument to this paper, that the argument was supported by evidence, and that the argument says something about a world broader than your specific paper topic. Hook, Line, and Sinker: Writing Effective Papers in Political Science 8