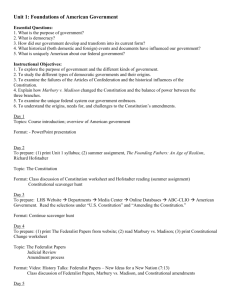

USHUnit1Questions.doc - sls

advertisement