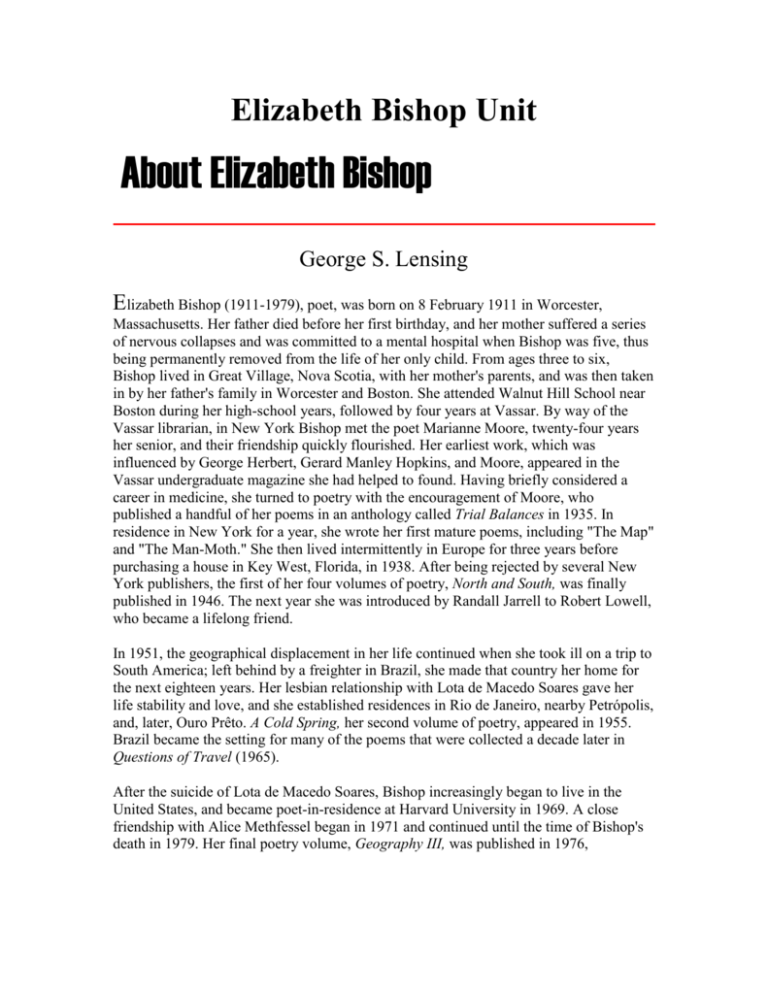

Elizabeth Bishop Unit

About Elizabeth Bishop

George S. Lensing

Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), poet, was born on 8 February 1911 in Worcester,

Massachusetts. Her father died before her first birthday, and her mother suffered a series

of nervous collapses and was committed to a mental hospital when Bishop was five, thus

being permanently removed from the life of her only child. From ages three to six,

Bishop lived in Great Village, Nova Scotia, with her mother's parents, and was then taken

in by her father's family in Worcester and Boston. She attended Walnut Hill School near

Boston during her high-school years, followed by four years at Vassar. By way of the

Vassar librarian, in New York Bishop met the poet Marianne Moore, twenty-four years

her senior, and their friendship quickly flourished. Her earliest work, which was

influenced by George Herbert, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Moore, appeared in the

Vassar undergraduate magazine she had helped to found. Having briefly considered a

career in medicine, she turned to poetry with the encouragement of Moore, who

published a handful of her poems in an anthology called Trial Balances in 1935. In

residence in New York for a year, she wrote her first mature poems, including "The Map"

and "The Man-Moth." She then lived intermittently in Europe for three years before

purchasing a house in Key West, Florida, in 1938. After being rejected by several New

York publishers, the first of her four volumes of poetry, North and South, was finally

published in 1946. The next year she was introduced by Randall Jarrell to Robert Lowell,

who became a lifelong friend.

In 1951, the geographical displacement in her life continued when she took ill on a trip to

South America; left behind by a freighter in Brazil, she made that country her home for

the next eighteen years. Her lesbian relationship with Lota de Macedo Soares gave her

life stability and love, and she established residences in Rio de Janeiro, nearby Petrópolis,

and, later, Ouro Prêto. A Cold Spring, her second volume of poetry, appeared in 1955.

Brazil became the setting for many of the poems that were collected a decade later in

Questions of Travel (1965).

After the suicide of Lota de Macedo Soares, Bishop increasingly began to live in the

United States, and became poet-in-residence at Harvard University in 1969. A close

friendship with Alice Methfessel began in 1971 and continued until the time of Bishop's

death in 1979. Her final poetry volume, Geography III, was published in 1976,

Bishop often spent many years writing a single poem, working toward an effect of

offfhandedness and spontaneity. Committed to a "passion for accuracy," she re-created

her worlds of Canada, America, Europe, and Brazil. Shunning self-pity, the poems thinly

conceal her estrangements as a woman, a lesbian, an orphan, a geographically rootless

traveler, a frequently hospitalized asthmatic, and a sufferer of depression and alcoholism.

"I'm not interested in big-scale work as such," she once told Lowell. "Something needn't

be large to be good."

Manuscript holdings are at the Houghton Library, Harvard University; the Rosenbach

Museum and Library, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; the Vassar College Library; and the

Washington University Libraries.

From The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States. Copyright ©

1995 by Oxford University Press.

Anne Agnes Colwell

Bishop, Elizabeth (8 Feb. 1911-6 Oct. 1979), poet, was born in Worcester,

Massachusetts, the daughter of Gertrude Bulmer and William Thomas Bishop, owners of

the J. W. Bishop contracting firm. Bishop's childhood was filled with a sense of loss that

pervades her poetry. Her father died from Bright's disease when she was eight months

old. Her mother, psychologically distraught, spent the next five years in and out of

psychiatric hospitals. With William's death, Gertrude lost her U.S. citizenship and, when

she experienced the decisive breakdown in her family home in Nova Scotia, was

hospitalized in a public sanatorium in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. Elizabeth Bishop was five

when this breakdown occurred; she later recounted it in her prose masterpiece "In the

Village." Her mother, diagnosed as permanently insane, never saw Elizabeth again.

After her mother's hospitalization, Bishop lived in Great Village, Nova Scotia, with her

mother's family, in a loving, comforting atmosphere. However, the equilibrium that she

had gained was upset by her paternal grandparents' decision to raise the child with them

in Worcester. In her prose memoir "The Country Mouse," Bishop writes,"I had been

brought back unconsulted and against my wishes to the house my father had been born in,

to be saved from a life of poverty and provincialism." There, in isolated wealth, Bishop

keenly felt her lack of relations. She wrote, "I felt myself aging, even dying. I was bored

and lonely with Grandma, my silent grandpa, the dinners alone. . . . At night I lay

blinking my flashlight off and on, and crying."

When her mother's sister, Maud Bulmer Shepherdson, rescued Bishop in May 1918, even

her paternal grandparents saw that their "experiment" had failed. Never a strong child,

Bishop now suffered from eczema, asthma, St. Vitus's dance, and nervous ailments that

made her nearly too weak to walk. Maud Shepherdson lived in an apartment in a South

Boston tenement. An unpublished manuscript, "Mrs. Sullivan Downstairs," recounts

Bishop's love for this neighborhood. There, Bishop later recalled, she began to write

poetry, influenced by Aunt Maud's love of literature.

As she grew stronger, Bishop spent her summers in Nova Scotia and attended Camp

Chequesset on Cape Cod. Her unusual circumstances and poor health limited her formal

schooling before age fourteen. However, she was an excellent student, and following her

time at the Walnut Hill School for Girls, Bishop entered the Vassar College class of

1934.

At Vassar, Bishop, with novelist Mary McCarthy and others, began an underground

literary magazine, Con Spirito, publishing a more socially conscious and avant-garde

selection than the legitimate Vassar Review. In the spring of 1934, the year her mother

died and the year of her graduation, Bishop met and became friends with poet Marianne

Moore. Through Moore's influence, Bishop came to see poetry as an available, viable

vocation for a woman. Moore recommended Bishop for the Houghton Mifflin Prize, and

Bishop's manuscript North and South was chosen for publication in August 1946 from

over 800 entries.

North and South introduces the themes central to Bishop's poetry: geography and

landscape, human connection with the natural world, questions of knowledge and

perception, and the ability or inability of form to control chaos. Before Robert Lowell

reviewed North and South, he met Bishop at a dinner party, a meeting that marked the

beginning of a crucial, if complicated, friendship. Lowell, like Moore, showed Bishop

possibilities--practically, in the form of grants, fellowships, and awards, and artistically.

In 1950 Lowell helped Bishop secure the post of poetry consultant for the Library of

Congress while she worked on her second book.

Bishop won the Lucy Martin Donnelly Fellowship from Bryn Mawr College in 1950 and

an award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1951 she traveled to South

America to see the Amazon. However, before she could leave for the dreamed-of voyage,

Bishop ate a cashew fruit to which she had a violent allergic reaction that kept her

bedridden. As Bishop recovered her health, she fell in love, both with Lota de Macedo

Soares, her friend and nurse, and with the landscape and culture of Brazil. For fifteen

years Bishop lived with Soares, in the mountain town of Petropolis and in Rio de Janeiro.

This new love and home offered Bishop happiness she had known only briefly in Great

Village. She wrote to Lowell that she was "extremely happy for the first time in my life"

(28 July 1953).

In April 1954 Bishop made an agreement with Houghton Mifflin to publish her second

book, A Cold Spring, in a volume that included the poems from her first book, under the

title Poems: North and South--A Cold Spring. This book won the 1956 Pulitzer Prize.

When the book appeared in August 1955, the reviews were laudatory: Donald Hall called

Bishop "one of the best poets alive."

After publishing A Cold Spring, Bishop spent the next three years translating a popular

Brazilian work, the diary of "Helena Morely" (Dona Alice Brant) called Minha Vida de

Menina. The story of Helena's life in the small town of Diamantina in 1893 reminded

Bishop of her 1916 Great Village, and translating this work while reflecting on and

writing about her own childhood helped Bishop explore her past as artistic material. The

translation was published under the title The Diary of Helena Morely by Farrar, Straus,

and Cudahy in 1957.

Bishop's third book, Questions of Travel (1965), includes both reflections on her

childhood experiences and poems about her new home in Brazil. The book is divided into

two sections, Brazil and Elsewhere, with the prose piece "In the Village" placed between

the divisions. Bishop returns to themes of geography, form, and landscape, but here she

allows more intimacy, both between viewer and landscape and between reader and poet.

Questions of Travel garnered positive reviews. Robert Mazzocco in the New York Review

of Books (Oct. 1967) called Bishop "one of the shining, central talents of our day." The

book is filled with the description for which Bishop received so much praise, but it is also

filled with an unmistakable sense of what Wyatt Prunty calls "the askew," moments in

which the senses fail to report reality, slide off into the mysterious, terrifying, or ecstatic.

Throughout the mid-1960s, life in Brazil grew difficult for Bishop. Lota de Macedo

Soares, involved in the politics of Rio, had taken charge of a public parks project that

absorbed her time and attention. As the political situation worsened, Bishop felt more

uncomfortable in her Brazilian home. In 1966 Bishop spent two semesters as poet in

residence at the University of Washington but returned to Rio in the hope of

reestablishing her life there. Both Bishop and Soares suffered physical and psychological

distress and were hospitalized in Brazil. When Bishop grew stronger, she left for New

York with the expectation that Soares, as soon as she was well enough, would join her.

Soares arrived in New York on the afternoon of 19 September 1967 and later that

evening took an overdose of tranquilizers and died at age fifty-seven.

This loss proved terribly difficult for Bishop personally, although she continued to write

and publish. In 1969 Bishop published Complete Poems, a volume that included all of her

previously published poems and several new pieces. This book won the National Book

Award for 1970. When the ceremony took place, Bishop was once again trying to

reestablish a Brazilian life. However, the politics, along with Bishop's inability to

negotiate the culture without Soares's help, finally convinced her that a Brazilian life was

impossible. In the fall of 1970 she returned to the United States to teach at Harvard.

There Bishop met the woman who became a source of strength and love for the rest of

her life, Alice Methfessel.

Bishop eventually signed a four-year contract with Harvard. Although she never felt

completely comfortable as a teacher, her students report learning much from her

precision, from the quiet conversation that constituted her class. In 1976 Bishop became

the first American and the first woman to be awarded the Books Abroad/Neustadt

International Prize for Literature. In that year she also published her last collection of

poetry, Geography III, which won the Book Critics' Circle Award for 1977. This volume

of nine beautifully crafted poems returns to themes of North and South but with greater

intimacy and immediacy. Alfred Corn, writing in the 1977 Georgia Review, gives a clear

and insightful reading of Geography III that could apply to all Bishop's work. He praises

a perfected transparence of expression, warmth of tone, and a singular blend of sadness

and good humor, of pain and acceptance--a radiant patience few people ever achieve and

few writers ever successfully render. The poems are works of philosophic beauty and

calm, illuminated by that "laughter in the soul" that belongs to the best part of the comic

genius.

When Bishop submitted her application for a Guggenheim Fellowship on 1 October

1977, she indicated that she would work on a new volume, tentatively titled

"Grandmother's Glass Eye," and a book-length poem, Elegy. Four poems of the new

volume, "Santarem," "North Haven," "Pink Dog," and "Sonnet," were complete when

Bishop died in Boston, Massachusetts. Bishop's poems have been collected in The

Complete Poems, 1927-1979, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux (1983).

Bibliography

Elizabeth Bishop's papers are in both the Houghton Library, Harvard University, and

Vassar College Library special collections. Brett C. Millier's biography Elizabeth Bishop:

Life and the Memory of It (1993) is a valuable resource, as is Candace W. MacMahon's

bibliography Elizabeth Bishop: A Bibliography, 1927-1979 (1980). Other important

critical assessments of Bishop's work include Bonnie Costello, Elizabeth Bishop:

Questions of Mastery (1991); David Kalstone, Becoming a Poet (1989); Jeredith Merrin,

An Enabling Humility: Marianne Moore, Elizabeth Bishop, and the Uses of Tradition

(1990); Robert Dale Parker, The Unbeliever: The Poetry of Elizabeth Bishop (1988); and

Thomas Travisano, Elizabeth Bishop: Her Artistic Development (1988). Her prose is in

The Collected Prose (1984), with a helpful introduction by Robert Giroux. Giroux also

edited and published Bishop's letters, masterpieces in themselves, in One Art: Letters

(1994). An obituary is in the New York Times (8 Oct. 1979.

Source: http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01885.html; American National Biography

Online Feb. 2000. Access Date: Sun Mar 18 16:53:45 2001 Copyright (c) 2000 American

Council of Learned Societies. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

From The Modern American Poetry Homepage

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/index.htm

Questions of Travel

“As you set out for Ithaka

hope your road is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.”

-Cafavy

“I have discovered that all human

evil comes from this, man’s being

unable to sit still in a room”

Blaise Pascal

“Travelling is a fool’s paradise. Our first journeys discover to us

the indifference of places. At home I dream that at Naples, at Rome,

I can be intoxicated with beauty and lose my sadness. I pack my trunk,

embrace my friends, embark on the sea, and at last wake up in

Naples, and there beside me is the stern fact, the sad self, unrelenting,

Identical, that I fled from. I seek the Vatican and the palaces. I affect

to be intoxicated with sights and suggestions, but I am not intoxicated.

My giant goes with me wherever I go.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

“And this gray spirit yearning in desire

To follow knowledge like a sinking star,

Beyond the utmost bound of human thought.”

Alfred Lord Tennyson

Questions of Travel

There are too many waterfalls here; the crowded streams

hurry too rapidly down to the sea,

and the pressure of so many clouds on the mountaintops

makes them spill over the sides in soft slow-motion,

turning to waterfalls under our very eyes.

--For if those streaks, those mile-long, shiny, tearstains,

aren't waterfalls yet,

in a quick age or so, as ages go here,

they probably will be.

But if the streams and clouds keep travelling, travelling,

the mountains look like the hulls of capsized ships,

slime-hung and barnacled.

Think of the long trip home.

Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?

Where should we be today?

Is it right to be watching strangers in a play

in this strangest of theatres?

What childishness is it that while there's a breath of life

in our bodies, we are determined to rush

to see the sun the other way around?

The tiniest green hummingbird in the world?

To stare at some inexplicable old stonework,

inexplicable and impenetrable,

at any view,

instantly seen and always, always delightful?

Oh, must we dream our dreams

and have them, too?

And have we room

for one more folded sunset, still quite warm?

But surely it would have been a pity

not to have seen the trees along this road,

really exaggerated in their beauty,

not to have seen them gesturing

like noble pantomimists, robed in pink.

--Not to have had to stop for gas and heard

the sad, two-noted, wooden tune

of disparate wooden clogs

carelessly clacking over

a grease-stained filling-station floor.

(In another country the clogs would all be tested.

Each pair there would have identical pitch.)

--A pity not to have heard

the other, less primitive music of the fat brown bird

who sings above the broken gasoline pump

in a bamboo church of Jesuit baroque:

three towers, five silver crosses.

--Yes, a pity not to have pondered,

blurr'dly and inconclusively,

on what connection can exist for centuries

between the crudest wooden footwear

and, careful and finicky,

the whittled fantasies of wooden cages.

--Never to have studied history in

the weak calligraphy of songbirds' cages.

--And never to have had to listen to rain

so much like politicians' speeches:

two hours of unrelenting oratory

and then a sudden golden silence

in which the traveller takes a notebook, writes:

"Is it lack of imagination that makes us come

to imagined places, not just stay at home?

Or could Pascal have been not entirely right

about just sitting quietly in one's room?

Continent, city, country, society:

the choice is never wide and never free.

And here, or there . . . No. Should we have stayed at home,

wherever that may be?"

Filling Station

Oh, but it is dirty!

—this little filling station,

oil-soaked, oil-permeated

to a disturbing, over-all

black translucency.

Be careful with that match!

Father wears a dirty,

oil-soaked monkey suit

that cuts him under the arms,

and several quick and saucy

and greasy sons assist him

(it’s a family filling station),

all quite thoroughly dirty.

Do they live in the station?

It has a cement porch

behind the pumps, and on it

a set of crushed and greaseimpregnated wickerwork;

on the wicker sofa

a dirty dog, quite comfy.

Some comic books provide

the only note of color—

of certain color. They lie

upon a big dim doily

draping a taboret

(part of the set), beside

a big hirsute begonia.

Why the extraneous plant?

Why the taboret?

Why, oh why, the doily?

(Embroidered in daisy stitch

with marguerites, I think,

and heavy with gray crochet.)

Somebody embroidered the doily.

Somebody waters the plant,

or oils it, maybe. Somebody

arranges the rows of cans

so that they softly say:

ESSO—SO—SO—SO

to high-strung automobiles.

Somebody loves us all.

One Art

The art of losing isn't hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster,

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster.

- Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident

the art of losing's not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like a disaster.

Sestina

September rain falls on the house.

In the failing light, the old grandmother

sits in the kitchen with the child

beside the Little Marvel Stove,

reading the jokes from the almanac,

laughing and talking to hide her tears.

She thinks that her equinoctial tears

and the rain that beats on the roof of the house

were both foretold by the almanac,

but only known to a grandmother.

The iron kettle sings on the stove.

She cuts some bread and says to the child,

It's time for tea now; but the child

is watching the teakettle's small hard tears

dance like mad on the hot black stove,

the way the rain must dance on the house.

Tidying up, the old grandmother

hangs up the clever almanac

on its string. Birdlike, the almanac

hovers half open above the child,

hovers above the old grandmother

and her teacup full of dark brown tears.

She shivers and says she thinks the house

feels chilly, and puts more wood in the stove.

It was to be, says the Marvel Stove.

I know what I know, says the almanac.

With crayons the child draws a rigid house

and a winding pathway. Then the child

puts in a man with buttons like tears

and shows it proudly to the grandmother.

But secretly, while the grandmother

busies herself about the stove,

the little moons fall down like tears

from between the pages of the almanac

into the flower bed the child

has carefully placed in the front of the house.

Time to plant tears, says the almanac.

The grandmother sings to the marvelous stove

and the child draws another inscrutable house.

The Moose

For Grace Bulmer Bowers

From narrow provinces

of fish and bread and tea,

home of the long tides

where the bay leaves the sea

twice a day and takes

the herrings long rides,

where if the river

enters or retreats

in a wall of brown foam

depends on if it meets

the bay coming in,

the bay not at home;

where, silted red,

sometimes the sun sets

facing a red sea,

and others, veins the flats’

lavender, rich mud

in burning rivulets;

on red, gravelly roads,

down rows of sugar maples,

past clapboard farmhouses

and neat, clapboard churches,

bleached, ridged as clamshells,

past twin silver birches,

through late afternoon

a bus journeys west,

the windshield flashing pink,

pink glancing off of metal,

brushing the dented flank

of blue, beat-up enamel;

down hollows, up rises,

and waits, patient, while

a lone traveller gives

kisses and embraces

to seven relatives

and a collie supervises.

Goodbye to the elms,

to the farm, to the dog.

The bus starts. The light

grows richer; the fog,

shifting, salty, thin,

comes closing in.

Its cold, round crystals

form and slide and settle

in the white hens’ feathers,

in gray glazed cabbages,

on the cabbage roses

and lupins like apostles;

the sweet peas cling

to their wet white string

on the whitewashed fences;

bumblebees creep

inside the foxgloves,

and evening commences.

One stop at Bass River.

Then the Economies—

Lower, Middle, Upper;

Five Islands, Five Houses,

where a woman shakes a tablecloth

out after supper.

A pale flickering. Gone.

The Tantramar marshes

and the smell of salt hay.

An iron bridge trembles

and a loose plank rattles

but doesn’t give way.

On the left, a red light

swims through the dark:

a ship’s port lantern.

Two rubber boots show,

illuminated, solemn.

A dog gives one bark.

A woman climbs in

with two market bags,

brisk, freckled, elderly.

“A grand night. Yes, sir,

all the way to Boston.”

She regards us amicably.

Moonlight as we enter

the New Brunswick woods,

hairy, scratchy, splintery;

moonlight and mist

caught in them like lamb’s wool

on bushes in a pasture.

The passengers lie back.

Snores. Some long sighs.

A dreamy divagation

begins in the night,

a gentle, auditory,

slow hallucination....

In the creakings and noises,

an old conversation

—not concerning us,

but recognizable, somewhere,

back in the bus:

Grandparents’ voices

uninterruptedly

talking, in Eternity:

names being mentioned,

things cleared up finally;

what he said, what she said,

who got pensioned;

deaths, deaths and sicknesses;

the year he remarried;

the year (something) happened.

She died in childbirth.

That was the son lost

when the schooner foundered.

He took to drink. Yes.

She went to the bad.

When Amos began to pray

even in the store and

finally the family had

to put him away.

“Yes ...” that peculiar

affirmative. “Yes ...”

A sharp, indrawn breath,

half groan, half acceptance,

that means “Life’s like that.

We know it (also death).”

Talking the way they talked

in the old featherbed,

peacefully, on and on,

dim lamplight in the hall,

down in the kitchen, the dog

tucked in her shawl.

Now, it’s all right now

even to fall asleep

just as on all those nights.

—Suddenly the bus driver

stops with a jolt,

turns off his lights.

A moose has come out of

the impenetrable wood

and stands there, looms, rather,

in the middle of the road.

It approaches; it sniffs at

the bus’s hot hood.

Towering, antlerless,

high as a church,

homely as a house

(or, safe as houses).

A man’s voice assures us

“Perfectly harmless....”

Some of the passengers

exclaim in whispers,

childishly, softly,

“Sure are big creatures.”

“It’s awful plain.”

“Look! It’s a she!”

Taking her time,

she looks the bus over,

grand, otherworldly.

Why, why do we feel

(we all feel) this sweet

sensation of joy?

“Curious creatures,”

says our quiet driver,

rolling his r’s.

“Look at that, would you.”

Then he shifts gears.

For a moment longer,

by craning backward,

the moose can be seen

on the moonlit macadam;

then there’s a dim

smell of moose, an acrid

smell of gasoline.