Chapter One - FacStaff Home Page for CBU

advertisement

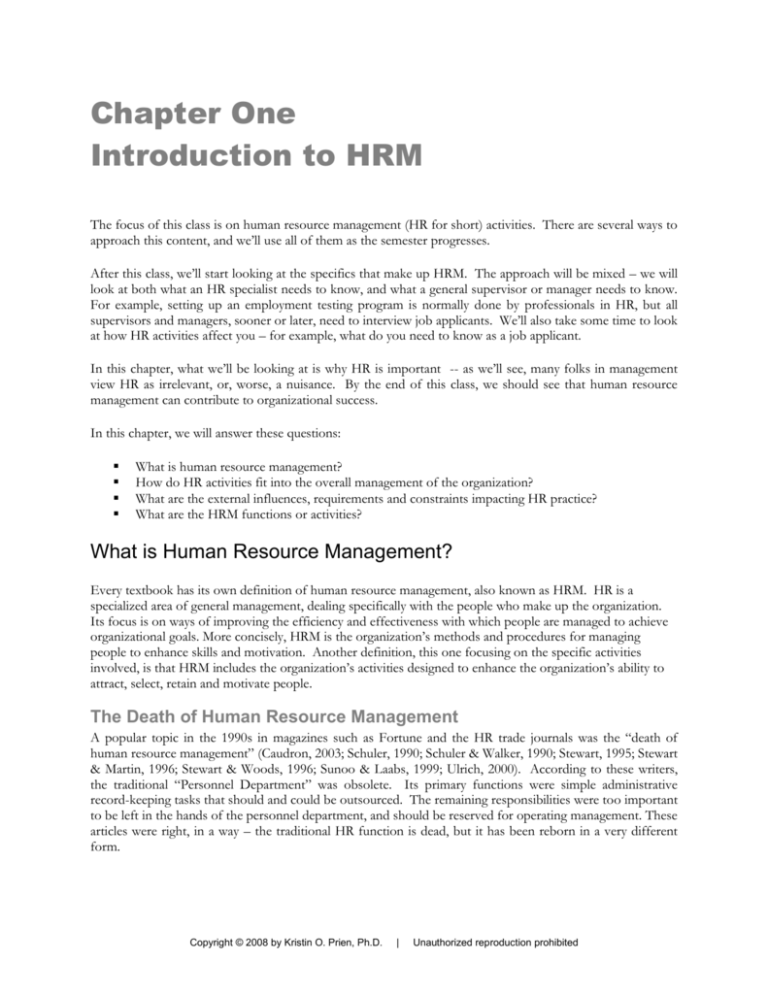

Chapter One Introduction to HRM The focus of this class is on human resource management (HR for short) activities. There are several ways to approach this content, and we’ll use all of them as the semester progresses. After this class, we’ll start looking at the specifics that make up HRM. The approach will be mixed – we will look at both what an HR specialist needs to know, and what a general supervisor or manager needs to know. For example, setting up an employment testing program is normally done by professionals in HR, but all supervisors and managers, sooner or later, need to interview job applicants. We’ll also take some time to look at how HR activities affect you – for example, what do you need to know as a job applicant. In this chapter, what we’ll be looking at is why HR is important -- as we’ll see, many folks in management view HR as irrelevant, or, worse, a nuisance. By the end of this class, we should see that human resource management can contribute to organizational success. In this chapter, we will answer these questions: What is human resource management? How do HR activities fit into the overall management of the organization? What are the external influences, requirements and constraints impacting HR practice? What are the HRM functions or activities? What is Human Resource Management? Every textbook has its own definition of human resource management, also known as HRM. HR is a specialized area of general management, dealing specifically with the people who make up the organization. Its focus is on ways of improving the efficiency and effectiveness with which people are managed to achieve organizational goals. More concisely, HRM is the organization’s methods and procedures for managing people to enhance skills and motivation. Another definition, this one focusing on the specific activities involved, is that HRM includes the organization’s activities designed to enhance the organization’s ability to attract, select, retain and motivate people. The Death of Human Resource Management A popular topic in the 1990s in magazines such as Fortune and the HR trade journals was the “death of human resource management” (Caudron, 2003; Schuler, 1990; Schuler & Walker, 1990; Stewart, 1995; Stewart & Martin, 1996; Stewart & Woods, 1996; Sunoo & Laabs, 1999; Ulrich, 2000). According to these writers, the traditional “Personnel Department” was obsolete. Its primary functions were simple administrative record-keeping tasks that should and could be outsourced. The remaining responsibilities were too important to be left in the hands of the personnel department, and should be reserved for operating management. These articles were right, in a way – the traditional HR function is dead, but it has been reborn in a very different form. Copyright © 2008 by Kristin O. Prien, Ph.D. | Unauthorized reproduction prohibited Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 2 The Personnel Department Traditionally, the HRM function was known as “personnel,” and was a relatively powerless, low status staff function. Personnel managers kept records and issued paychecks. Many managers perceived it (and many still do) as irrelevant or ineffectual. In fact, up until about 20 years ago, “personnel” was primarily a recordkeeping function. It was the dumping ground for the inefficient and the folks not deemed worthy of “real” jobs in organizations – women and minorities. Some, in fact, believed that “personnel” was a dying function, that line management would take on many human resource functions, with the rest being outsourced. Would It Make More Sense To Outsource HR Functions? The idea of outsourcing HRM activities began in the 1980’s, when many firms contracted out payroll processing. It made sense. Payroll processing is a very detail-intensive, yet routine job. A specialist contractor, running payrolls for many companies, can achieve economies of scale – and, thus, do it cheaper than many firms can do on their own. So, the thought was, let’s try it with other HR functions. Now, outsourcing is a $6 billion per year business (Babcock, 2006), and some projections (Rafter, 2005) have it as high as $14 billion by 2009. All areas of HR can be outsourced, from routine administrative functions such as benefits processing, to core HR activities, such as staffing and training (Caudron, 2003). A company can outsource specific tasks, such as payroll processing, or entire processes, such as recruitment or benefits administration (Greengard, 2004). An estimated 80% of companies outsource one or more HR functions (Caudron, 2003); other sources estimate that as many as 94% of firms are outsourcing at least one HR function (Gurchiek, 2005). Do companies save money through outsourcing? Is it a good idea, whether or not there are cost savings? The numbers indicate that there are cost savings. Service providers suggest that 15% to 25% cost savings are possible (Greengard, 2004). In actual practice, the savings can be significant. Estimates are that British Petroleum reduced HR costs by 20% (Rafter, 2005). Other firms save, though not as big. For example, Bank of America estimated a 10% savings from outsourcing payroll, HRIS (human resource information systems), benefits processing, and employee communications (Zimmerman, April 2001). And, there is the benefit, especially for smaller companies, of having specialists (that would otherwise be unaffordable) do the work – employee benefits, in particular, is an extremely complex and specialized area. Finally, in a recent survey, 89% of firms that outsourced were pleased with their results (Gurchiek, 2005). Not all outsourcing transitions are as smooth as projected. When British Petroleum contracted with Exult to handle a portion of its HR functions, there were difficulties and problems – for example, a promised payroll system proved to be impractical outside of English-speaking locations. BP employees, facing the loss of their jobs, had little reason to work to make the transition work (Rafter, 2005). Incidentally, was this a groundless fear? Probably not – HR staff went from 100 people to 35 people (Caudron, 2003). Opponents argue that, while it makes sense to outsource routine activities (i.e., payroll or insurance claim processing), functions such as staffing, which are directly related to a firm’s core competencies – its people – should remain within the firm. If the fit between employee and the company is critically important, who should make the decision to hire or not hire? When a firm makes the decision to outsource, it is critical to take the time to select the best service provider. It’s also important to remember that, no matter how much or little is outsourced, it is critical to keep control over the provider’s activities – as far as employees are concerned (and, often, legally), the company is still responsible. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 3 HR Professionals Today As we said previously, the reports of the impending death of the HRM function were somewhat exaggerated. What we saw, instead, was a rebirth. Part of this rebirth has been a change in who practices HR. Recent estimates are that 25% to 30% of today’s HR executives came from a line area (such as manufacturing or sales), rather than from HR (Caudron, 2003). In another move, many HR professionals are rotating to areas outside of HR. But, HR professionals have also taken steps to change their image and, more importantly, their capabilities. HR practitioners realized that, to be taken seriously, to be a “strategic business partner,” they needed to bring more to the table than just the ability to keep records and a vague desire to “work with people”. In fact, HR professionals recognize the need for an enhanced skill set; in a recent survey of HR managers, over half pointed to the absence of strategic and quantitative thinking as the major reason for HR departments being downsized (Dunn, 2000). So, what are these skills? Figure 1: Why HR Departments are Downsized (Adapted from Dunn, 2000) 35% 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% Results not measurable Not effectively marketed to management Not in line with Unpopular with business strategy employees Overstaffed None of above Quantitative Thinking CEO’s and senior managers view decision-making in financial terms. HR folks traditionally viewed themselves as “people persons,” but learned that it was essential to be able to show how their activities paid off, in financial terms. For example, GTE uses the “balanced scorecard” approach, measuring every conceivable aspect of HR performance. With their results, HR staff are able to show, in dollars and cents terms, how much the HR function contributes to GTE’s profits (Solomon, 2000). As we’ll see later in this chapter, additional techniques from finance and accounting can be valuable in assessing the value of an organization’s people and making decisions about people. Quantitative information is not, as yet, as widely used as it can be. 91% of companies collect so-called “metrics,” this data, but less than half (46%) actually use this information to measure the value of their employees (“People are our greatest asset,” 2005). One manager who relies on quantitative information and analysis is the vice president of HR at Bal Seal Engineering, Jeff Jernigan. His entire approach to managing Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 4 HR is based on numbers – not just payroll costs and staffing numbers, but complex statistical analyses, including correlation and multiple regression. The result, based on sales and production information, are used to predict exact staffing needs (Lachnit, 2001; “Greatest asset”, 2005), but in a recent survey, 84% of HR managers reported that the use of quantitative measurement and decision-making will increase in the near future (Hansen, 2005). Strategic Thinking In order to be involved in top-level decisions, it’s essential to think strategically. That means focusing on the overall organization, not just that narrow segment marked “Human Resources.” HR managers need to see how the effective management of human resources can fit into the organization’s overall strategy, and, more importantly, develop HR programs that carry out the overall strategy. There’s evidence that this shift has occurred. In a recent survey (“Flexibility moves to center stage”, 2004), 61% of HR managers reported that they had complete, or at least substantial, involvement in organizational strategic planning and implementation. In a more recent survey conducted by the Society of Human Resource Management, certified human resource professionals reported pending from one-third to half of their time dealing with “strategic / policy responsibilities” (McConnell, 2007). In support of this, over half of the HR managers surveyed report to the company’s CEO. In other instances, HR managers become themselves part of company strategy. Finally, in a 2001 study of HR managers, 30 out of 537 surveyed had risen to a senior management position, 10 to the CEO slot (Wells, 2003). Let’s look at some actual examples. At Hallmark Cards, the overall company vision statement, “Enriching Lives and Relationships,” became the starting point for an entire package of family-friendly policies and programs (Atkinson, 2005). At FPI Thermoplastic Technologies, HR manager Claudia Rowe became involved with company strategy to the point that she assumed responsibility for international sales, as well as her HR responsibilities (Stewart & Martin, 1996). Knowledge of the Business The needs and requirements of a manufacturing company are different from those of a bank, and both differ from what is needed at a hospital or retail chain. The differences are not just between industries. The needs of different banks will be also be different. For example, think about the complexities of recruitment and selection of a very large state-wide bank, such as First Tennessee, with the needs of a small, 2 or 3 branch bank. HR managers and professionals with experience in the firm or industry in areas other than HR have an advantage here, through their knowledge of the business and business requirements. For example, Borders realized that half of their book-buying customers were 45 years or older. In order to better appeal to those customers, Borders is focusing recruiting on people aged 50 and older. Turnover is significantly lower in this age group. Finally, with an aging population, the pool of younger workers who traditionally filled retail jobs is shrinking. The end result – a solution to worker shortages that actually results in better employees (Marquez, 2005). In another example, the on-line application at Las Vegas casino Wynn Las Vegas is specifically designed for the casino industry; instead of typing in the name of previous employers, applicants choose from a menu listing all of the Las Vegas casinos (Berkshire, 2005). Certification and Professional Organizations As do most professions and industries, the field of human resource management has its professional associations. Perhaps the most well-known is the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), with over 200,000 members. Others include the American Society for Training and Development, the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans and the International Public Management Association Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 5 for Human Resources. As do other professional associations, these groups engage in educational and professional development activities, conduct surveys and other applied research, monitor pending legislation and legal cases (often also engaging in lobbying activities) and, often, fund university scholarships for students interested in becoming HR professionals. Finally, the professional HR groups also, increasingly, provide opportunities for practitioners to gain certification, attesting to the individual’s expertise in the general field of HRM or a specialized area (such as training or benefits administration). In fields such as law, medicine and accounting, practitioners hold licenses and certifications to attest to their expertise. While HR practitioners do not require licensure or certification, there is a growing trend for HR practitioners to hold one or more certifications. Through SHRM and other organizations, there are several types and levels of certification for HR professionals. The SHRM certification dates from 1976, when the sponsoring organization was known as the American Society of Personnel Directors or ASPA; by 2006, it is estimated that 80,000 or more individuals hold one of the SHRM certifications. (Leonard, 2006). The ASPA certifications were followed by the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans and its Certified Employee Benefit Specialist (CEBS) certification. Other professional associations have followed. These two are probably the best-known and most accepted. Other certifications, such as the ones offered by the International Coach Federation are less well-known and are held by very few individuals --- less than 1,500 (Laff, 2007). Certification is normally based on the results of examinations; in addition, applicants for certification often must also have documented work experience in the HR area. The certifying organizations offer review classes to prepare applicants for the exams, and these classes are often a requirement for taking the exam. Current estimates are that over a third of HR directors and VP’s hold a certification, although certification is not as yet a requirement for working as an HR professional or manager (Sunoo & Laabs, 1999). Many HR professionals, though, do find that certification gives them an advantage in seeking jobs in the field (Dinell, 2003). There is, though, evidence on the other side; an academic study found that less than 1% of on-line advertisements for HR professionals specified that a certification was required or even desirable (Aguinis, Michaelis, & Jones, 2005). Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 6 Figure 2: HRM Professional Organizations and Certifications American Payroll Association (www.americalpayroll.org) Fundamentals of Payroll Certification (FPC) Certified Payroll Professional (CPP) American Society for Training & Development ( www.astd.org) Human Performance Improvement Certificate Certified Performance Technologist Human Resource Certification Institute [affiliated with SHRM] ( www.hrci.org) Professional in Human Resources (PHR) Senior Professional in Human Resources (SPHR) Global Professional in Human Resources (GPHR) International Coach Federation ( www.coachfederation.org) Associate Certified Coach Professional Certified Coach Master Certified Coach International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans ( www.ifebp.org) Certified Employee Benefits Specialist Compensation Management Specialist Group Benefits Associate Retirement Plans Associate International Public Management Association for Human Resources ( www.ipma-hr.org) IPMA-Certified Specialist IPMA-Certified Professional Society for Human Resource Management (www.shrm.org) Approaches to Revitalizing HR There are two general approaches that are taken in the reborn HRM field – first, there is accounting for human resources; and, second, managing people for competitive advantage. Earlier, we said that HR managers needed to be able to think both quantitatively and strategically. These two approaches draw on those skills. Thinking quantitatively leads to treating people as any other asset, and applying techniques from accounting and finance to the management of human resources. Thinking strategically leads to the idea of competitive advantage, the strengths that a firm can build a strategy around. For the HR manager, that translates to how a firm can create and sustain competitive advantage through its people. Accounting for Human Resources These are two approaches to measuring people’s contributions to the company. It’s important to remember that measurement is important – people don’t see something as important unless it can be measured. The reverse is true, too -- what is measured is, therefore, important. The techniques used here draw on cost accounting and basic finance. One is not better or worse than the other – the two approaches answer different questions. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 7 Costing HR Wayne Cascio, a professor at the University of Colorado, realized as far back as 1982 that cost accounting techniques could easily be applied to HR activities. How does this work? Basically, what you are doing is calculating the cost of HR interventions and the cost savings resulting from the outcomes. For example, let’s look at the costs associated with employees quitting and having to be replaced. First, how do we measure turnover? It’s based on the number of employees we have and how may quit and are replaced over the course of (usually) a year. So, if you begin the year with 10 employees, and end the year with 10 different employees, you have 100% turnover over the course of a year. More realistically, some employees may still be with you at the end of the year, while others stay less than a year. Let’s assume that we have 100 employees and 200% turnover. This means you have to hire 200 new employees every year. What are some of the costs? Some are obvious – ads, application forms, employment tests, drug testing, etc. But others are not as obvious, such as the time it takes HR staff and management to screen and select candidates. The second step is to compare the costs of turnover with the costs of reducing turnover. For example, you might reduce turnover to 50% by increasing salaries by 4%. Should you do this? Compare the cost of hiring 100 fewer people each year with the cost of a 3% salary raise. Let’s look at Figure 3 to compare the costs. In this case, the cost of a 3% raise is more than what would be saved with a reduction in turnover. But, what if the price of drug testing drops? The turnover rate increases? Then, the pay raise might be worthwhile. This approach can be more complex. Going back to employment – you might be trying to decide whether to run an employment ad in the local newspaper or in the Wall Street Journal. Obviously, the local paper will be much less expensive. What you have to consider, though, is whether or not you’ll get the applicants you are looking for from the ad in the local newspaper. The Wall Street Journal ad might be three times as expensive, but produce 10 times as many good applicants. So, the Wall Street Journal ad is actually lower cost per applicant. Think longer term, too. Which source provides employees who perform better? Stay with the company longer? A large bank recruited employees primarily from top-ranked MBA programs; these employees performed somewhat better than the recruits from less-prestigious programs, but left the organization at a much higher rate (Garvey, 2005). Figure 3: Potential Savings From Hiring 100 Fewer New Employees Costs to Hire Employment ad (6 60 day ads on Monster.com @ $300) Clerical time to process applicants (1 hour @ $7.50 x 500 applicants) Initial screening interview (1 hour @$9.00 x 400 applicants) Employment testing ($35 x 300 applicants) Supervisor interview / decision making (1 hour @$15.00 x 250 applicants) Pre-employment drug screen ($50 x 150 applicants) Reference checking (1 hour @ $9.00 x 125 applicants) Supervisor time to train new employees (5 hours @$15 / hour x 100) $1,800 3,750 3,600 10,500 3,750 7,500 1,125 7,500 Total Hiring Costs $39,525 Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 8 Cost of 3% Raise 100 employees x $7.00 per hour x 40 hours per week x 52 weeks per year $1,456,000 Total Cost of Raise $43,680 Total Savings (Cost) $4,155 Making cost – benefit comparisons isn’t all that you can do with HR cost information – or, as it also called metrics. It’s possible to track costs and other information over time, to determine if HR is becoming more or less effective. For example, you may be taking 60 days, on average, to fill vacant positions. After implementing a new procedure for processing resumes, that time might drop to 55 days – an improvement. You can also compare your metrics to those of other companies; this is the “balanced scorecard” or “benchmarking” approach (Solomon, 2000). This can be industry averages or you may pick a specific company that you’ve identified as being someone to emulate (“Five steps to effective metrics”). If, for example, the industry average tie to fill a vacant position is 45 days, you’ve improved, but need to improve even more. Some suggestions for the use of metrics (Bates, 2003; “Five steps”, 2005): Do collect data that allows you to determine how well HR is supporting the organization’s overall strategy. Don’t just copy another organization’s metrics. Develop the numbers that your organization needs to measure. Don’t try to get too complicated. Make sure management can understand the numbers and what they mean. Do use comparisons. Numbers by themselves don’t tell you anything; instead, compare results over time, or with other organizations. Human Capital Approach What are your company’s assets? The obvious answer – buildings, inventory, equipment – is only a partial answer. What is an asset? It’s any item that has value. Your employees are an asset – specifically, their knowledge, skills, expertise, dedication – are assets, too, even if you can’t tattoo an inventory control number on their foreheads. The idea of intangible assets isn’t new – think about goodwill, for example. And, it’s possible to value any intangible asset. One approach to valuing your organization’s employees is the human capital approach (Stewart, 1995; Zimmerman, February 2001). Here’s how to proceed. The value of your employees is determined by calculating how much more effectively your company operates with your employees. How do we determine how effectively your company operates? One obvious way is to look at earnings. So, to determine the contribution of employees to corporate earnings, follow these steps: Determine three years’ total pretax earnings Determine average assets over same three years Calculate firm’s return on assets (ROA) Determine industry average ROA Calculate “excess returns1” Excess returns represent a return on assets over and above what other firms in the same industry are earning. Excess returns are attributable to something intangible, not reflected on a balance sheet. 1 Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 9 Subtract taxes Calculate net present value of excess return The result of these calculations is the “intangible value” of the company’s human capital. Human Resources and Competitive Advantage The human capital approach is based on the assumption that we have the best employees and that those employees are contributing to our bottom line. However, there’s one important point to keep in mind when thinking of employees as assets – they are assets with feet. Your employees leave every night, and there’s no guarantee that they will return the next day. So, how do you go about acquiring, managing, and retaining your workforce? In other words, how do we go about establishing and maintaining competitive advantage through people? First of all, what is competitive advantage? It is the factor or factors that give your company an edge or advantage over your competitors – let’s call it X. It could be: High-quality products Superior customer service Lowest cost products Location Product performance Product reliability Value (quality + service + price) Competitive advantage is something that is valuable. And, in order for something to be valuable, it has to be rare (if you could pick up diamonds in the parking lot, would they be valuable?). Also, in order for X, whatever it is, to be an advantage, it has to be something that not everyone else has. Thus, it must be difficult or impossible to copy (inimitable) and there can’t be any substitute for X (nonsubstitutable). Competitive advantage has to be created, but just as importantly, sustained. Firms such as Sears, IBM, and virtually the entire US airline industry have learned the results of failing to maintain competitive advantage. Competitive advantage is the foundation of a firm’s strategy – the idea is to make the optimal use of whatever competitive advantage or advantages the firm has, in order to accomplish the organization’s goals (such as profit). WalMart, for example, is able, because of its size, to purchase products at low prices – their competitive advantage would be either low cost or value. When we buy groceries in Memphis, we go to WalMart for low prices, Kroger for location, and Seessel’s (or we did…now we go to Schnuck’s) for highquality products and customer service. But, it’s also important to remember that we don’t acquire and sustain competitive advantage through strategy, but rather through strategy implementation. Where does competitive advantage come from? There are numerous sources, but, according the management professor Jeffrey Pfeffer, the most important is people. People are hard to imitate or duplicate, and traditional sources of competitive advantage are no longer as effective as they once were. Traditional Sources of Competitive Advantage…and Where They’ve Gone What are some of the traditional sources of competitive advantage – and where have they gone (Pfeffer, 1998)? Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 10 Product and process technology: Number one. With the pace of technological innovation becoming faster and faster, a firm can no longer develop a product, protect it with patents, and rest on their laurels. Xerox, for example, was once protected from competition by their hold on key patents. 3M does compete with better products, but they can develop superior products on a continuous basis because of their people. Also, it is important to remember that technology is available to everyone. If you buy superior manufacturing equipment, so can your competitors. Finally, if you rely on advanced technology to be competitive, you had also better have the people necessary to operate that technology. For example, if your grocery store installs automated checkout scanners, you’ll need more qualified people – it’s no longer necessary to have a lot of low-skilled checkers, but you will need highly skilled network administrators. Protected and regulated markets: The growing global economy is based, in part, on the idea of free trade – reduced barriers to trade between countries. So, an industry or firm can no longer rely on the government to prevent the importation of cheaper or better competing goods. The U.S. steel industry is currently protected by tariffs. However, the industry hasn’t been able to count on this protection for most of the past 30 years, and has been in a steady decline for those same thirty years. Deregulation, too, matters. For example, telecommunications was once the monopoly of A T & T. No longer. Access to financial resources: Between NASDAQ, venture capital, and even folks’ personal credit cards, it’s no longer necessary to have access to the big New York financial markets to raise capital. Economies of scale: In manufacturing, larger companies traditionally had a competitive advantage because of economies of scale. That is, if your business requires a large capital investment, it’s cheaper to make many of something than just a few. However, economies of scale don’t guarantee competitive advantage today. Due to market fragmentation, customers are less interested in a cheap standardized product than in a customized product. Also, inventory management has moved to “just-in-time”, meaning that it’s more important and more cost-effective for a manufacturer to be able to deliver small quantities on a precise schedule, rather than making a huge batch at one time. Competitive Advantage Through People In order to establish and maintain competitive advantage through people, it’s necessary to make a complete reversal in our traditional thinking about employees. Look at any financial statement – payroll and other employee costs (such as training) are listed as an expense. To base completive advantage on employees’ unique capabilities, you need to start looking at your employees as an asset, instead. The work force should be an asset. When a company spends that much on equipment, the equipment is taken care of and maintained, and the company doesn’t spend the money to buy the equipment until they are sure that the equipment is the best equipment. For example, First Tennessee, in 2006, reported 10.35% return on equity to its shareholders – a respectable return on investment, by any definition. It’s no wonder Our culture is what makes us unique. It's our "secret weapon" to success. It is a combination of our vision, mission and our philosophy of putting "employees first." We know that without excellent employees we will not be able to provide outstanding service to our customers, shareholders or communities. At First Tennessee/First Horizon, we call our culture Firstpower. Firstpower is how we do business. It is the attitude of ownership and teamwork each employee brings to the job every day. All employees are company owners and as owners we: Recognize that a job well done is the first order of business. Are empowered to take care of customers -- internal and external. Create a flexible work environment so we can embrace both our personal lives and responsibilities at work. Know that what we create at work is a reflection of ourselves and as such, only the absolute best is good enough. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 11 that First Tennessee has made this statement (source: www.firsttennessee.com) How does this work? If your employees are an asset, you invest in them, the same way you invest in any other asset. For employees, it isn’t a coat of paint or preventative maintenance; it’s training and development. The result – employees are more skilled, more competent, and can “work smarter.” If your employees are an asset, you treat them with respect and dignity,, letting them know they are valued. The result – employees are more committed to the company and involved in their work and “work harder.” Finally, if your employees are an asset, you make the most effective use possible of the asset. With employees, that means taking advantage of their capabilities and motivation to push responsibility down to employees, rather than relying on supervisors and managers. The result -- lower overhead. One other important piece of advice – Think Long-Term Building a workforce into an asset isn’t something that happens overnight. It takes time and patience. What can you do to create a high-performing workforce? Pfeffer (1998) points to what he calls the seven practices of high performance work systems. Let’s look at them. High-Performance Work Systems: The Seven Practices As you look at each of these seven practices, you’ll see that they work as a system. In other words, each practice depends on the other six being in place. For example, if you invest in training, that’s a good reason to avoid any unnecessary layoffs. Why invest in your employees, then just throw them away? Employment Security: First, layoffs are a last resort. Before even considering letting employees go, you cut executive pay. Discount broker Charles Schwab & Co. didn’t immediately lay employees off when business took a downturn in 2000. First, travel and entertainment were cut. Next, management pay was cut, from the VP level and up – including a 50% pay cut for the CEO. When it was apparent that these measures wouldn’t be enough, some employees were laid off, though with extremely generous severance packages, including a $7,500 bonus for employee rehired within 18 months and a $20,000 tuition voucher paid for by the founder (Cascio, 2002). When there’s no choice, lay people off humanely – that means severance pay, outplacement help, extended health benefits. And allow people to leave in a dignified manner. This doesn’t mean that nobody is ever fired – you still terminate people for poor performance, but you also look at an honest mistake as a learning experience. If people lose their jobs for trying something new, you’ll have a company full of people doing the same old thing as before. Selective Hiring: If you’re going to keep people, make sure you hire the best. Take the time to figure out what you really need. This means that you need to think about what your jobs require and what the organization needs. Think, too, about what can be learned after someone is hired, versus what can’t be acquired. You can teach a person computer skills – you can’t teach conscientiousness. Take your time; if you don’t have the time to carefully evaluate new hires, you certainly don’t have time to come back in six months and do it again, when the first hire doesn’t work out. Plus, if you’re that busy, you certainly don’t have time to go back and fix the mistakes the first person made! Finally, a lengthy hiring process sends a message to your employees – “We took the time to hire the best.” For example, more and more firms are taking the approach that you should hire for attitude, especially when their competitive advantage is built on customer service, as in the case of Disney. Southwest Airlines uses a similar approach, and much of its success is credited to its employees. Both Disney and Southwest have Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 12 become models for other companies, in industries ranging from airlines to hospitals (Greengard, 2003; Shuit, 2004). Self Managed Teams and Decentralized Decision Making: If you have good folks that you can trust and rely on, push decision-making further down in the organization. This works better for the organization – decisions are made by folks with the information, rather than by “headquarters.” Also, decisions can be made quickly. You certainly don’t want a customer to wait for “approval from Chicago” before getting that 5% discount that convinces them to buy. People are more motivated by the added responsibility and authority and by the opportunity to better use their brains and skills. In an industry characterized by fierce competition and declining profitability, Wegmans Food Market stands apart. Exact numbers are hard to come by – Wegmans is a privately held company – but estimates are that margins are double the industry average and sales per square foot are half again as much as the competition. Wegmans was ranked as Fortune’s Best Company to Work for in 20052 and the chain boasts a fanatic level of customer loyalty. At Wegmans, participation is a way of life. Employees are encouraged to take whatever steps are needed to ensure customer satisfaction – without consulting management. One senior management team member was quoted (only partly in jest) as saying, “we’re a $3 billion company run by 16 year old cashiers” (Boyle & Kratz, 2005) High Compensation, Based on Organizational Performance: When you pay people well, you’re sending them another signal – you matter, you’re important. We know that pay doesn’t keep people, but high pay levels make it easier to attract a large applicant pool, which is essential if you’re going to be selective in your hiring. Finally, and most important, is to pay people more for better performance. If the company is making profits through employees’ skills and effort, pass some of it along. And, by hiring the right people and providing the training, there’s no reason that employees won’t perform and receive the rewards for performance. Think, too, about using stock ownership as a motivating tool, not just for executives, but for all employees. One of the classic examples of the payoff from high, performance-based compensation is Lincoln Electric. This Cleveland, Ohio based manufacturer of arc-welding equipment is known for its compensation system, where production workers are paid by production, and a year-end bonus. Plant employees can end up with a six-figure total income; the average bonus for 2000 was over $17,000 (Eisenberg, Sieger, & Greenwald, 2001). In fact, Lincoln Electric ran short of cash in 1992, and actually borrowed money to pay the year-end bonuses (Hastings, 1999). That didn’t hurt the company – in 2005, Fortune recommended Lincoln Electric as one of its eight choices for high-performing small companies (“Small wonders,” 2005). Extensive Training: Obviously, the more skills your employees have, the better, and training is important. This is especially critical in today's environment, where technology is rapidly changing, and skills become obsolete overnight. Also, if you’re going to decentralize and give people more responsibility, they need more skills. Employees also need teamwork skills (which don’t appeal by magic) if they’re going to be working in teams. And, if you’re going to invest in training, pick the best people and plan on keeping them around. For example, Minnesota Life, the seventh-largest life insurance company in the U.S., believes in training. The firm spends over $2,000 per year training each IT employee (significantly higher than the industry average). Newly hired employees are required to go through two to three weeks training before beginning their jobs. The result – numerous awards for the quality of work life and the quality of the company’s IT solutions. Incidentally, Minnesota Life is also highly rated by industry experts (Mullich, 2004). Reduced Status Distinctions: Treat your employees as though they are important, not as though they are peasants. It’s easy to call people “associates” and talk about how people matter, but act as though you mean 2 Wegmans ranked #2 on the 2006 Fortune list and #3 on the 2007 list Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 13 it. Get rid of the executive dining room, reserved parking, first class plane tickets, and lavish offices. Keep executive salaries in line, too. Extensive Information Sharing: If you plan on decentralizing, people need the information. Also, sharing company-wide information builds a sense of trust between the company and employees, and you need that sense of trust for people to give the company their committed efforts. And, you can share information when you have committed, long-term employees that you trust. For example, at Google, company financial information is shared with employees at weekly Friday afternoon meetings (Raphael, 2003). At Whole Foods, employees are privy to so much information that each employee is classified as an “insider” by the SEC (Pfeffer, 1998). Among other information, each store has a book, where the salaries of very company employee are listed (Fishman, 2004). Now. Let’s look at three examples of how this approach works. These are from research studies, each looking at a large sample of companies, so that we can see what happens across a range of companies. Notice, too, that the three studies we look at each use different methods and measurements to establish the link between HR practices and performance, making it even more clear that this isn’t just coincidence. The Research Evidence Each of these examples is based on a large sample of firms, meaning that these are the average results. Any one company may not see the improvements that the average company does, though some may see much better results. Bear in mind., too, that this is only three examples out of a large number of these studies. The 100 Best Companies to Work For. Fortune publishes an annual list of the 100 best companies (in the USS) to be employed by. Based on employee survey data, ranking are based on such factors as respect, caring and pride in one’s work. The question, of course, is whether or not the best companies to work for are the most profitable. A group of researchers decided to examine this question (Fulmer, Gerhant, & Scott, 2003). Their results indicate that the best companies to work for, when compared with other, similar firms, show significantly higher return on assets, as well as higher overall return to stockholders. 000 of Employees Garment Manufacturing: Garment manufacturing has traditionally been a low-skill, assembly-line type of manufacturing. As with other manufacturing, garment factories are a thing of the past in the U.S. Look at any piece of clothing you’re wearing – you’ll see Pakistan, Bangladesh, China – almost Employees in U.S. Garment Industry anything but the U.S. One 1970 - 2002 solution to the problem of fleeing jobs is to increase 1,000 worker productivity in American plants. The best500 known approach to increasing productivity is modular 0 manufacturing. The traditional 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 garment assembly line (what’s called “bundle” manufacturing) has each worker doing one small takes – sewing on a pocket, for example – over and over. With modular manufacturing, workers are organized into small, self-managed teams. Each team is responsible for an entire work process and workers are expected to be able to move around within the module, performing different tasks as needed. Employees Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 14 are paid on a piecework basis, just as in the bundle system, but it’s now a group incentive, rather than an individual incentive. The results are remarkable (Bailey, 1993; Pfeffer, 1998). Bundles vs. Modules in Garment Manufacturing Performance Measure Bundle Modular Gross margin 26.0% 31.6% Operating profit 7.9% 13.0% Sewing throughput (days) * 9.5 days 1.8 days * the time it takes to make a shirt, from start to finish The Minimills. This study (Arthur, 1994) looked at steel minimills – small facilities that start with scrap rather than ore. The authors identified two HR strategies followed by the mills. A control strategy was based on the assumption that employees needed to be monitored. The focus was on efficiency and reduced costs. A commitment strategy was based on mutual trust and the objective was to have the employees share the company’s goals. As you can see, the control strategy does result in lower costs on a per-hour basis, but look at the reductions in labor hours per ton of steel produced and the scrap rate. Management Practice Control Commitment % Improvement Wages $18.07 $21.52 19% % of employees in teams 36.6% 52.4% 43% Decentralization * 2.42 3.04 26% General training * 1.92 3.35 74% Labor hours / ton - 34% Scrap rate - 63% * 1 = very little to 6 = very much The Case of the IPOs. In this study, the researchers (Welbourne & Andrews, 1996) looked at the fate of new companies (IPO stands for initial public offering, the company’s first sale of stock on the open market). The authors picked a random sample of firms filing for IPOs in 1988, then looked how these companies valued people. They went to the prospectuses (which are legal documents), and extracted information about how people were treated – they created an index for general HR value, and a second index reflecting how employees were rewarded (especially if rank-and-file employees were eligible for stock options). Then, the researchers went forward in the records to 1993 and looked at what had happened to these companies. As you can see from the chart above, being in the top 16% on either of the HR measures, as opposed to being in the bottom 16%, made a significant difference as to whether or not the firm was still in business 5 years later. It’s worth noting that about half of IPO’s don’t survive – so raising the chances to 87% of better is a meaningful improvement. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 15 Why Not? The Downward Performance Spiral Ok. You’d think that everyone would know about these results, and everyone would follow the practices. But, as we know, that’s not the case. Too often, HR is seen as a frill – profits are down, so let’s cut training expenses. However, cutting expenses through people often leads to problems becoming worse, and you get a selfreinforcing downward cycle. As described by Pfeffer (1998), you see something like this: What happens is simple – a firm experiences financial problems, and reacts by cutting HR costs. By reducing their investment in people, the company’s performance goes into a further decline….. Many people do take a short-term view, and believe that cutting the costs associated with the organization’s people will lead to higher profits. We’ll discuss this more when we get to downsizing, but for right now, let’s look at a few examples of what not to do. The Case of Chainsaw Al In 1996, struggling appliance manufacturer Sunbeam brought in a so-called turnaround expert to rescue the firm, Al Dunlap, also known as “Chainsaw Al.” Dunlap promised results, in return for a $1,000,000 salary, plus enough stock options to bring him over $40 million. The restructuring began with plant closings and layoffs of 50% of the company’s 12,000 employees. Neither the former employees nor the remaining workforce were happy with Chainsaw Al; rumor had it that Dunlap found it necessary to invest in a bulletproof vest and handgun, as well as hiring bodyguards (all at Sunbeam’s expense). Shareholders, though, were pleased – 1997 sales were 1.16 billion, up by 22%, and Sunbeam stock rose from $11.25 to $53 a share. Plans were announced for Sunbeam to acquire three other companies. Sunbeam was the miracle turnaround, and Chainsaw Al was the darling of the business press. However, in 1998, Dunlap’s house of cards began to collapse. It seems that those 1997 sales were massively inflated. Dunlap had pressured Sunbeam’s customers into ordering vast quantities of product, at least several years’ worth, though no deliveries were made, nor the products paid for. By June of 1998, the board of directors had discovered he problem, and promptly fired Dunlap. Even those employees who were still with Sunbeam were happy to see the end of Chainsaw Al. One employee was quoted as saying, “I popped open a bottle of champagne when I heard the news “ (Kadlek, Marchant & Drummond, 1998, p. 46). Sunbeam was eventually forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and was eventually restructured under new ownership. Under threat of a shareholder lawsuit, Dunlap agreed to pay Sunbeam shareholders $15 million and in a settlement with the SEC, Dunlap agreed to pay a $500,000 fine. And, the man who fired employees in the name of profits is no longer employable – the SEC has barred Dunlap from ever again serving as an officer or director of a publicly held firm3 Sources include Anderson, 1999; Byrne & Prasso, 2002; Haysett, 2002; Kadlek, Marchant, & Drummond, 1998; Schifrin, 1998; Sellers, 1998 3 Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 16 WalMart and the Value of HR WalMart, at one point a poster child for good management practices (Pfeffer, 1994, 1998), has lost much of its glitter in recent years. The company that rewarded line managers and looked on HR as a waste of time and money has discovered the dollars-and-cents value of professional HR management. In recent years, WalMart has been: Cited and fined for overtime violations, specifically, forcing workers to put in unpaid hours, even locking employees into stores. Caught using undocumented workers (i.e., illegal aliens) to clean stores. Although these workers were technically employed by independent contractors, not WalMart, WalMart recently paid an $11 million fine to settle the case. Civil suits and suits under RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act) are pending. Named as the defendant in of one of the largest class-action employment discrimination lawsuits filed. The plaintiffs allege that WalMart discriminates against women, in particular for promotion to management positions. Accused of pushing its employees onto public healthcare plans, rather than paying sufficient wages to allow employee to participate in the company health plan. The target of serious organizing attempts by the UFCW (United Food and Commercial Workers) Perhaps not surprisingly, in 2002, WalMart hired a high-profile VP for human resources and most recently announced plans to add HR professional staff to support store operations; currently WalMart is testing this approach in California, and if it successful, will expand it nationwide4. Changing the Organization How does an organization go about changing? It isn’t a quick or easy process. There’s some evidence that the high-performance work practices model is easier to implement in so-called “greenfields.” That is, it’s easier to start a new facility (the “greenfield”) with the new practices in place from the beginning than to change practices and culture in an already-existing facility. This isn’t to say that change can’t happen – it can, but you may need as long as 5 to 15 years to bring about real (and lasting) change in how an organization manages its people. It’s critical to remember that these practices can’t be implemented individually – they all act as a self-reinforcing system, and it’s critical to change the entire system (Neal & Tromley, 1995). To begin with, many organizations get caught up in committees, studies, and planning. All that does is put off actually doing something. This isn’t to say that organizations should act without any thinking at all – but it does mean that thought needs to be transformed into action (Pfeffer, & Sutton 1999). Strategic HRM: Putting the Pieces Together Now. How precisely do we take the idea of competitive advantage through people and the high-performance work practices and put them into place? Look at the example of Google. This is a firm that, more than most, depends on people. Thus, to a greater extent than most firms, Google’s assets have feet and walk out the door every night. The question is, how do you make sure that those feet walk back in the next morning? Google’s workforce is highly skilled – in fact, many of their employees come from Ph.D. programs (note that their recruiting ads run in Scientific American). 4 Sources include Castelli (2005), Hegstrom, (2003), Riley (2004), Serwer, Bonamici & Hajim (2005). Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 17 How do you attract, retain and motivate this type of employee? Google provides a friendly, relaxed work environment, and a generous package of benefits. Job applicants sit in beanbag chairs, breakfast, lunch and dinner and provided free, and there’s even an on-site washer and drier (Raphael, 2003). Would the same strategy work for a different company? Maybe, maybe not. Think about a company on the complete opposite end of the spectrum, McDonald’s. McDonald’s competes, as we know, on price. In addition, systems and procedures in each restaurant have been established to all but remove the possibility of human error. Would it make sense, than, for McDonald’s to spend as much money and time to recruit and take care of its front line employees as does Google? The whole point of the systems – such as cash registers with pictures and automatic drink dispensers – is to remove the possibility of human error. If people can’t make performance worse, can they make it better? A recent survey conducted by Pricewaterhousecoopers found that concrete, written plans to align HR strategy with business strategy paid off, with 35% higher revenues per employee (Bales, 2003). How to go about this? Determine the firm’s strategy Determine the competencies needed to carry out the strategy Examine current management practices Determine congruence Do the current practices work to enhance needed competencies? Are the current practices internally consistent? External Influences on HRM It’s critical to remember that no organization – anywhere from Federal Express to the corner hamburger stand – operates in a vacuum. The external environment sets boundaries, limits and requirements for how the organization functions. Economic factors, political, legal and social factors, and technology all influence how an organization operates in general, and, specifically, in how it manages its human resources. Economic conditions As we said earlier in this chapter, human resource management is, in large part, about money and how the organization uses its financial resources to achieve and sustain competitive advantage. Thus, economic factors are a very important influence on the practice of HR. Global Economy The growing global economy has an impact on labor supply and demand. Unskilled jobs – such as textiles and garment manufacturing – have long been moved to countries with lower labor costs. A new trend, though, is the overseas movement of high-tech jobs. This industry, that conventional wisdom said was a U.S. preserve, is losing jobs to India. Jobs ranging from customer service to high-end programming and systems analysis are being relocated to India, a country where labor costs are significantly lower, and productivity is equal to, if not better than, the U.S. (India has a very strong IT industry, and some of the best schools in the world in this area). It’s estimated that over 3 million jobs will be lost in the U.S. over the next 12 years (“Where the good jobs are going,” 2003). Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 18 There are ethical issues involved with this shift, especially in industries that employ unskilled workers, many of whom we would consider children, and too young to work in a factory. Politics also plays a role here. The U.S. has used tariffs (import taxes) on foreign steel and textiles, in part to protect voters’ jobs. Domestic Factors The U.S. has shifted away from a reliance on a manufacturing to an information / service economy. This shift impacts HR in many ways. Workers now need more skills than ever before. Jobs no longer require nothing more than strength and the willingness to work. Today’s jobs require more than a high school education. The fastest growing jobs require at least some post-secondary education, but there is also numerical growth in jobs at the bottom of the service economy. The decreased importance of manufacturing has also meant a less important role for organized labor. While there are a large number of union members – 16.1 million workers – these workers represent only about 13% of the labor force.5 And, in an information / service economy, your people are your only real assets. As we’ve said, they walk out of the door each night, and your challenge is to make sure they walk back in the next morning. Other economic factors include the trend towards more and more mergers and acquisitions. These also impact labor markets – when organizations merge and functions are duplicated, we see layoffs. This is obviously bad for the laid-off employees (and for companies that produce the goods and services that individual formerly purchased), but good for employers, who have a larger labor supply, available at lower prices. Finally, don’t forget about our old friends from economics, Mr. Supply and Mr. Demand. There’s the supply and demand of labor, which influences the price you must pay to hire people. Even supply and demand of your company’s goods and services matters – the better your sales, the more resources you have available to use to enhance your labor force. Legal Requirements and Constraints We view government as being the intermediary in the relationship between employer and employee. For the most part, the intermediary role of government is to ensure that organizations conform to what society as a whole has agreed are minimum standards for employment. For example, child labor was generally accepted during the 19th century and even into the twentieth century. By 1939, when the Fair Labor Standards Act (or FLSA – you’ll see this abbreviation again) was passed, society, for the most part, had decided that children should not be working for wages6. Most folks accept the idea of a minimum wage, another FLSA provision. For more information about union membership, go to the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, or directly to http://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.toc.htm). 5 6 For a fascinating look at the history of the FLSA, see www.dol.gov/asp/programs/history. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 19 A few people, and some municipalities have gone further, to what’s known as a “living wage7.” However, the idea of a “living wage” hasn’t even begun to hit the mainstream, and may never do so. While HR professionals are normally not attorneys, some understanding of legal requirements and constraints is very important, both to avoid getting into trouble in the first place, and to know what questions to ask your in-house or outside counsel. Demographics Here, we are looking at the people who are available – who they are, what skills they have, their motivation, their needs (both material and psychological). New skills are needed Look back to the economic changes discussed above – specifically, the move to an information / service economy. We need workers with different skills, and often skills acquired through a higher level of education than in previous years. See the opposite page for the jobs preduictred to have the highest growth in the next 10 years. Where will we find those workers? Even the jobs at the bottom of the pyramid – the cashiers, food service workers, home health aides, and so forth, require basic skills, such as the ability to read and write, the ability to do simple arithmetic, and general work readiness. If workers don’t have those skills, is it the employer’s responsibility to train workers? Could it be a business necessity? Increasing number of women in paid workforce Over the past 40 years, women have moved into the paid workforce, and are looking at paid work as a lifelong career, rather than a stopgap before raising a family. Who, then, takes care of childcare and (important now with an aging population) elder care? If organizations can’t accommodate these needs (for both male and female employees), they run the great risk of overlooking talent they need in order to remain competitive. Many areas of work – such as benefit plans and work hours -- have traditionally assumed a family structure of working husband, with a wife not working for pay and 2.3 children. If this ever existed, it certainly does not exist today. So, how do we structure work (flextime, time off) and employee benefits to accommodate the needs of different families, including single parents and dual earner families? Aging population Over the next ten years, the number of people ages 65 and above will increase by 26% (Cole, et al, 2003). What’s going to happen to pension plans, health care, and Social Security when the folks born 1947-1964 (“baby boom”) begin to retire? Will they be able to retire? Will the retirement age be raised? Look for this issue to be a hot topic in politics in coming elections. Living Wage: For a family of 4 to be above the poverty line, one worker must earn at least $8.20 per hour, working full time. Other definitions go up to $12 per hour, especially in communities with an extremely high cost of living. 7 Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 20 Fastest Growing Occupations, 2006 – 2016 (by number of jobs) Job Growth (000) Training Required RN 587 Associate degree Retail salespersons 557 Short on-the-job Customer service representatives 545 Moderate on-the-job Combined food preparation and serving workers, including fast food 452 Office clerks, general 404 Short on-the-job Personal and home care aides 389 Short on-the-job Home health aides 384 Short on-the-job Post-secondary teachers 382 Doctoral degree Janitors and cleaners, except maids and housekeeping cleaners 345 Nursing aides, orderlies, and attendants 264 Short on-the-job Short on-the-job Short on-the-job Fastest Growing Occupations, 2002 – 2012 (by %) Job Network systems and data communications analysts Growth 53.4% Training Required Bachelor's degree Personal and home care aides 50.6% Short on-the-job Home health aides 48.7% Short on-the-job Computer software engineers, applications 44.6% Bachelor's degree Veterinary technologists and technicians 41.0% Associate degree Personal financial advisors 41.0% Bachelor's degree Makeup artists, theatrical and performance 39.8% Postsecondary vocational Medical assistants 35.4% Moderate on-the-job Veterinarians 35.0% Post-secondary professional degree Substance abuse and behavioral disorder counselors 34.3% Bachelor's degree Changes in Expectations With the wave of layoffs and downsizings over the past 25 years, there is no longer the unspoken “contract” between employer and employee, made up of mutual loyalty and the expectation of a lifetime with a single employer. Many employers complain about a lack of loyalty – however, you don’t get what you don’t give. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 21 Technology Change in technology has been a theme of this section. Employers need new skills and more skills. Even more important is the ability to learn – as technology changes, employees need to be able to keep up with the changes. We see some jobs vanish, others appear: Old Jobs New Jobs Receptionist Telecommunications analyst Typesetter Desktop publishing specialist Bank teller Network administrator (ATM system) Technology has also made changes in HR operations. For example: Internet recruiting Automated application systems (i.e., “Press 1 to apply for a job now…”) Email / cellular phones (although this really affects business in general, not just HR) Employee communications via intranet Distance interviewing Distance learning for training Telework Resume scanning and applicant tracking Employee data online HR Functions: What We’ll Be Looking At Different textbooks break out the various HR functions differently – this is one way of doing it, though not the only way. Planning In human resource management, as with any other management activity, the first step is always planning. On the broadest level, HR planning involves determining the strategic direction that HR activities need to take in order to mesh with and support the organization’s overall strategy. Formulating plans to carry out strategy requires, first, information gathering, including the process and outcome data from HR activities discussed above (Accounting For Human Resources). An additional form of information gathering that we’ll discuss in the next chapter is job analysis, or the “systematic process of collecting relevant, work-related information related to the nature of a specific job.” Forecasting is also part of planning – what skills will be needed and how and where the organization will find or develop those skills. Legal Compliance Like it or not, all organizations are subject to laws and regulations, at the federal, state, and local level. The vast majority of HR activities, including employment, pay and benefits, employee rights, and labor relations, are subject to legal requirements and constraints. We’ll look at these in Chapters 3 and 4. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 22 Staffing The staffing process includes all of the steps needed to find, select, and terminate employees, from initial entry into the organization, through eventual retirement, discharge or downsizing. Recruiting and selection are the major activities here, but we are also concerned with career management (from the standpoint of the organization and from the employee’s perspective), downsizing and retirement. Reward Systems It goes without saying that employees are paid. However, we have to determine how much the various jobs within the organization are worth, since not all jobs are worth the same to the company – and nobody ever thinks they are paid enough! Systematic salary administration is critical to ensure that employees perceive that pay is being distributed fairly and equitably. In addition to base pay, we need to determine how best to use money and other rewards to motivate employees. Pay increases and the various forms of incentive pay merit their own chapter. Another essential part of reward systems is employee benefits; rather that paying for a job or for performance, employee benefits are designed to encourage employee retention. Training and Development As we discussed earlier in this chapter, one of the seven high performance work practices is extensive training. Training is especially critical in a work environment characterized by rapid and constant change – the skills you graduate with will almost certainly not be all of the skills you’ll need in your job five years from now. Organizations must determine what their training needs are, select appropriate training methods, and, finally, evaluate the results of training. In addition to specific skill training, if you have a long-term commitment to your employees, it’s important to consider their long-term development – moving from the mailroom to the CEO’s office isn’t a myth. Employee Relations The HR department in an organization is also responsible for managing the relationship between employer and employees. Employees may have complaints or grievances, that must be resolved, and the need for counseling and discipline is always there. Here, we’ll also look at the issue of employee rights – how far can or should an employer control and monitor employees. Finally, labor relations, specifically, the relationship between management and labor unions, is a critical function. Though fewer employees are members of labor unions today than the late 1930’s, many firms are still unionized, while others are attempting to avoid unionization. It’s essential for HR managers and professionals in those firms to have through knowledge of the labor movement, as well as the complicated legal restraints and requirements involved. Other Functions Several other areas may or may not be included in an organization’s HR department. They may be part of HR, they may be assigned to a different department or they may be outsourced; we won’t be looking at these areas. OSHA (Occupational Health and Safety Act) compliance and safety training are often a department of their own, and are often part of production management, especially in industrial settings). Payroll and HRIS (human resource information systems) are often outsourced, due to the technical complexities involved (Greengard, 2004). In smaller companies, payroll is often attached to accounting and finance. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 23 References and Suggestions for Further Reading Aguinis, H, Michaelis, S. E., & Jones, N. M. (2005). Demand for certified human resources professionals on internet-based job announcements. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 13(2), 160-171. Anderson, J. (October 1999). Al gets the chainsaw. Institutional Investor, p. 116. Arthur, J. B. (1994). Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 670688. Atkinson, H. (May/June 2005). Creating a “threedimensional” strategy at Hallmark Cards. Strategic HR Review, pp. 8-9. Babcock, P. (March 2006). HRMagazine, pp. 68-74. A crowded space. Bailey, T. (1993). Organizational innovation in the apparel industry. Industrial Relations, 32(1), 30-48. Bates, S. (April 2003). Written HR strategy pays off, study finds. HRMagazine, p.12. Bates, S. (December 2003). HRMagazine, pp. 50-55. The metrics maze. Boyle, M., & Kratz, E. K. (January 24, 2005). The Wegmans way. Fortune, pp. 62-66. Byrne, J. A., & Prasso, S. (January 28, 2002). Why Chainsaw Al opened his wallet. Business Week, p. 8. Cascio, W. F. (1982). Costing human resources in organizations: The financial impact of behavior in organizations. Boston: Kent Publishing. Cascio, W. F. (2002). Strategies for responsible restructuring. Academy of Management Executive, 16(3), 80-91. Castelli, E. (March 19, 2005). WalMart settles case on illegal cleaning crews for $11 million. Los Angeles Times, p. A22. Caudron, S. (January 2003). HR is dead – Long live HR. Workforce, pp. 26-30. Challenger, J. A. (July 2003). Solving the looming labor crisis. USA Today Magazine, pp. 28-30. Cole, C. L., Gale, S. F., Greengard, S., Kiger, P. J., Lachnit, C., Raphael, T., Shuit, D. P., & Wiscombe, J. (June 2003). 25 trends that will change the way you do business. Workforce, pp. 43-56. Dinell, D. (August 22, 2003). Climbing higher: Human resource professionals say certification can give careers a boost, Wichita Business Journal. Dunn, K. (March 2000). HR goes flat at Coca-Cola. Workforce, pp. 26, 28. Eisenberg, D., Sieger, M., & Greenwald, J. (June 18, 2001). Where people are never let go. Time, pp. 40-42. Fishman, C. (July 2004). The anarchist’s cookbook. Fast Company, pp. 70-78. “Five steps to effective metrics.” 2005). Strategic HR Review, p. 7. (March / April “Flexibility moves to center stage.” (December 2004). Workforce, pp. 86-92. Fulmer, I. S., Gerhart, B., & Scott, K. S. (2003). Are the 100 Best better? An empirical investigation of the relationship between “being a great place to work” and firm performance. Personnel Psychology, 56, 965-993. Garvey, C. (April 2005). The next generation of hiring metrics. HRMagazine, pp. 71-76. Greengard, S. (July 2004). Pulling the plug. Workforce, pp. 43-46. Gurchiek, K. (June 2005). Record growth in outsourcing of HR functions. HRMagazine, pp. 35, 38. Hansen, F. (March 2005). Heavy lifting ahead for metrics. Workforce, p. 21. Hastings, D. F. (May/June 1999). Lincoln Electric's harsh lessons from international expansion. Harvard Business Review, pp. 163-174. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 24 Haysett, D. (December 23, 2002). Sunbeam out of Ch. 11 with new name, structure. Home Textiles Today, pp. 2, 17. Hegstrom, E. (October 24, 2003). Agents raid two area WalMarts. Houston Chronicle, p. A29. Kadlek, D., Marchant, V., & Drummond, T. (June 29, 1998). Chainsaw Al gets the chop. Time, pp. 4647. Lachnit, C. (March 2001). World class results on a mom-and-pop budget. Workforce, pp. 42-43. Laff, M. (April 2007). The certified coach: A brand you should be able to trust. T & D, pp. 38-41. Leonard, B. (June, 2006). Certification Institute celebrates 30th year: Group gives HR credibility. HRMagazine, pp. 189-190. McConenll, B. (February 2007). Exams change with the HR profession. HRMagazine, pp. 127-128. Marquez, J. (May 2005). Novel ideas at Borders lure older workers. Workforce, pp. 28-29. Mullich, J. (October 2004). Minnesota Life takes the long view on IT hiring and training. Workforce, pp. 80-82. Neal, J. A., & Tromley, C. L. (1995). From incremental change to retrofit: Creating high-performance work systems. Academy of Management Executive, 9(1), 42-54. “People are our greatest asset.” (April 2005). HRMagazine, p. 20. Pfeffer, J. (1994). Competitive advantage through people: Unleashing the power of the work force. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. (available as an ebook through CBU library) Pfeffer, J. (1998). The human equation: Building profits by putting people first. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Pfeffer, J., & Sutton, R.I. (1999). Knowing `what' to do is not enough: Turning knowledge into action. California Management Review, 83-109. Rafter, M. V. (June 2005). Adventures in outsourcing. Workforce, pp. 51-55. Raphael, T. (2003, March). At Google, the proof is in the people. Workforce, pp. 50-51. Riley, M. (September 6, 2004). A new tack against WalMart. Denver Post, p. C1. Schifrin, M. (May 4, 1998). Forbes, pp. 44-45. The unkindest cuts. Schuler, R. S. (1990). Repositioning the human resource function: Transformation or demise? Academy of Management Executive, 4(3), 49-60. Schuler, R.S., & Walker, J. W. (1990). Human resources strategy: Focusing on issues and actions. Organizational Dynamics, 19(1), 4-20. Sellers, P. (January 12, 1998). Can Chainsaw Al really be a builder? Fortune, pp. 118-120. Serwer, A., Bonamici, K, & Hajim, C. (April 18, 2005). Bruised in Bentonville. Fortune, p. 84. Sheley, E. (June, 1996). HRMagazine, pp. 86-96. Share your worth. Shuit, D. P. (September 2004). Workforce, pp. 35-38. Magic for sale. “Small wonders.” (July 11, 2005). Fortune, pp. 34-35. Solomon, C. M. (March 2000). Putting HR on the score card. Workforce, pp. 94-97. Stewart, T. A. (April 13, 1998). A new way to think about employees. Fortune, pp. 169-170. Stewart, T. A. (October 2, 1995). Trying to grasp the intangible. Fortune, pp. 157-161. Stewart, T. A., & Martin, M. H. (May 13, 1996). HR bites back. Fortune, pp. 175-176. Stewart, T. A., & Woods, W. (January 15, 1996). Taking on the last bureaucracy. Fortune, pp.105106. Sunoo, B. P., & Laabs, J. (May 1999). Certification enhances HR's credibility. Workforce, pp. 70-77. “Where the good jobs are going.” (August 4, 2003). Time, pp. 36-38. Chapter One: Introduction to Human Resource Management Page 25 Ulrich, D. (January/February 1998). A new mandate for human resources. Harvard Business Review, pp. 124-134. Welbourne, T. M., & Andrews, A. O. (1996). Predicting the performance of initial public offerings: should human resource management be in the equation? Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 891-919. Wells, S. J. (June 2003). HRMagazine, pp. 46-49. From HR to the top. Wright, P. M., & McMahon, G. C. (1992). Theoretical perspective for strategic human resource management. Journal of Management, 18(2), 295-320. Zimmerman, E. (April 2001). B of A and big-time outsourcing. Workforce, pp. 51-53. Zimmerman, E. (February 2001). What are employees worth? Workforce, pp. 32-36.