Billboard Illustrated Encyclopedia of Opera

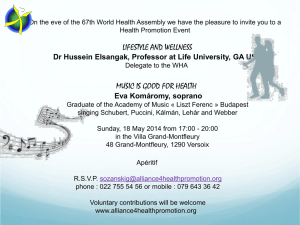

advertisement