Psychiatry`s Global Challenge

advertisement

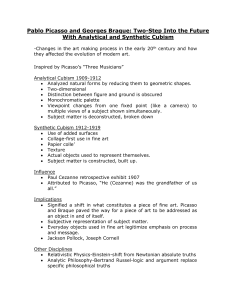

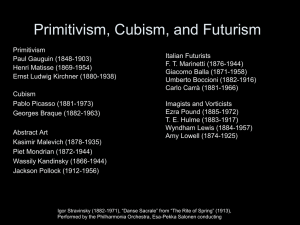

Painted Ladies By: Michael Fitzgerald From: Vogue, April, 1996 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 1. Today, it is almost impossible to separate artists’ lives from their work. Biography holds us spellbound and overwhelms mere works of art with the immediacy and drama of everyday life. Whether the figure is Marcel Duchamp or Andy Warhol, both of whom wholeheartedly acclaimed the unity of art and life, or a modern-day hermit such as Piet Mondrian or Jasper Johns, the stature of artists is increasingly defined by their public personas. The art becomes almost secondary, and a controversy in one’s private life can lead a respected career to be declared counterfeit. Witness Woody Allen. 2. Probably no artist is more subject to biographical fascination than Pablo Picasso, who sometimes seemed to have lived only for his art and to have painted his every plate of fish or tumble in bed. His torrid romances, flamboyant behavior, and great wealth seem to fulfill many of our fantasies and supply an excitement that some find lacking in the cerebral austerity of Cubism or the stark confrontations with geriatric decay of the painter’s last years. 3. Nowhere is the intermingling of transient affairs with permanent creations more problematic than in portraiture, and Picasso’s portraits are intimately bound up with his life. Only now are we realizing that the vast majority of them depict the women who shared his days and nights: Fernande and Eva, Olga and Marie-Therese, Dora, Francoise, and Jacqueline (to name only the major loves) stare out at us from the frames in endless variations. Traditionally, these women – always referred to by art historians by their first names – have been considered mere appendages of the artist. Now their increasing fame, and the sympathy their lives often inspire, make this false familiarity appropriate. Having once been nearly ignored, these women have emerged from the shadows of Picasso’s life to stand fully illuminated on the stage. They have even been described lately as dominant figures, ones who not only are portrayed in Picasso’s pictures but who reached beyond the passive role of pictorial subject to shape his art. 4. Most recently, Norman Mailer has joined the chorus of critics who ironically seek to empower Picasso’s women by presenting them as sometimes manipulative figures exerting control over a pliable Picasso. In Portrait of Picasso as a Young Man, Mailer claims that when Eva Goel entered Picasso’s life in late 1911, she prompted a fundamental decline in his art by smothering his avant-garde spirit under her frumpy tastes. Never mind that during these years Picasso and his collaborator Georges Braque were so deeply involved in inventing Cubism that they cautioned others to stay out of their business by quoting the sign posted in Parisian buses: Don’t talk to the driver. Forget the fact that the few contemporary descriptions of Eva reveal very Painted Ladies / 2 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 little about her personality, and that the petite, waif-like figure in photographs hardly suggests a controlling will (she died, probably of cancer, in 1915). Mailer nonetheless blames her for a change in Picasso’s art that he, at least, does not admire. Clearly, portraiture and the women in Picasso’s life have moved to the center of arguments over his art. 5. “Surviving Picasso”, the film that Ismail Merchant and James Ivory are currently making about the artist’s ten-year relationship with Francoise Gilot, looks to be the reductio ad absurdum of this viewpoint. Starring Anthony Hopkins as the 63year-old master and Natascha McElhone as the 23-year-old ingénue, the film will no doubt dwell on the passion and incongruity of this match between youth and age. Yet it now appears that the movie will not include a single painting by either Picasso or Gilot. The script deviates so far from the facts that Gilot has refused permission to use her book, Life with Picasso, and her children with Picasso, Claude and Paloma, have banned the filmmakers from reproducing any of their father’s art. Thus the movie will probably show fakes. Truly, life – at least Merchant and Ivory’s version of it – will have triumphed over art. 6. “Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation,” which open at the Museum of Modern Art in New York on April 28, enables us to confront this cardinal question. Organized by William Rubin, who previously orchestrated MoMA’s great 1980 retrospective of Picasso and “Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism: in 1989, the exhibition includes masterpieces from every phase of the artist’s career: the excruciating half-blind Celestina of the Blue Period, the majestic Gertrude Stain of the Rose, and the orgiastic Sleeping Nude (Marie-Therese) of the Surrealist phase, among many others. Rubin has used all the clout he has accumulated during a nearly 30-year career at MoMA to assemble more than 130 paintings (plus more than 70 drawings, 20 prints, and one sculpture) including many from private collectors whom only Rubin could persuade to lend, and others that have rarely been seen because they remain in the possession of the artist’s heirs. 7. In light of Rubin’s record, it is clear that he is not interested in simply assembling another extravagant showcase of Picasso’s art. His goal is far more ambitious. He wants to convince us not only that Picasso was the greatest portraitist of the twentieth century but that he fundamentally redefined portraiture – changed the way artists from Matisse to Warhol to Clemente paint the people around them. In order to demonstrate this feat, Rubin has cut deeply into the full range of Picasso’s portraits to choose a concentrated core – the essence, as he sees it. Since a large proportion of Picasso’s portraits are sketches dashed off in a few moments, Rubin has not tried to include every one of Picasso’s subjects. Instead, the exhibition focuses on the people Picasso portrayed most often and the ones he frequently chose for oil paintings: the women in his life. Thus the exhibition includes almost 20 portraits of Olga, more than 30 of Marie-Therese, and more than 20 of Dora and Jacqueline, to name only the largest groups. Painted Ladies / 3 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 8. Undoubtedly, some reviewers will criticize this slice for making it appear that Picasso created within a harem, cut off from the world. And most of us will struggle with the central puzzle of how Picasso’s volatile life with these women affected his art. If the exhibition delivers no definitive answer, it does present a controversial interpretation of the portraits, one that argues against a simple correspondence between life and art. By displaying many portraits of each woman, the exhibition lets us see the great variety of Picasso’s interpretations and allows us to test Rubin’s thesis: that Picasso pushed the genre far beyond simply recording a likeness of a particular individual or an episode in their lives. He reinvented portraiture as a medium of self-expression – a means to pass through the person before him and communicate to us his own deepest feelings, not only about people but also about the political and social events of his time. 9. Indeed, Picasso so transformed portraiture that we might wonder whether he actually destroyed it. This issue – to what extent these pictures are portraits of Olga or Jacqueline versus phantom projections of Picasso’s will – is the fundamental question confronting visitors to the exhibition, one to be grappled with from drawing to painting to sculpture. 10. Picasso did not arrive at a sweeping new definition of portraiture immediately. His earliest portraits are quite conventional, primarily images of his family, sometimes posing as characters in rather academic scenes. Even during his Blue and Rose periods and the early years of Cubism, Picasso perpetuated the conventional function of portraiture: to flatter the sitter in order to cultivate that person’s financial and critical support. This is the case with his portrait of Gertrude Stein, his most important early patron, and the 1910 trio of portraits of art dealers – Ambroise Vollard (the established representative of Renoir, Gauguin, and Cézanne), Wilhelm Uhde (an enthusiastic supporter of the avant-garde) and Daniel Henry Kahnweiler (who would become the greatest dealer of the twentieth century). The process of posing for these portraits was a courtship, one that finally resulted in a marriage between Picasso and Kahnweiler that would last, despite a long separation in midstream, for the rest of Picasso’s life. 11. These three paintings constitute Picasso’s only great portraits of men, and they signal the metamorphosis of his portraiture as well. Astonishingly, after his youth Picasso never painted a portrait of another artist, even Braque, and very few of the poets or critics who played essential roles in his career (although abundant drawings and caricatures record their presence). But in his portraits of Vollard, Uhde, and especially Kahnweiler, Picasso tapped these men’s profound sympathy with his art to create some of his greatest Cubist paintings. Having solidified his financial base and essentially freed himself of material worries, Picasso began to reverse the conventional expectations of portraiture: Now it became a means to embody his own ideas more than the personality of his ostensible subjects. 12. This distinction is little understood, yet it is crucial to the images of women that Painted Ladies / 4 120 125 130 135 140 145 150 155 will dominate his portraiture for the next six decades. These series begin with the grand, ceremonial portrait of Olga Khokhlova seated in an armchair that Picasso painted in the fall of 1917, nearly a year before their marriage. (Although the marriage officially endured until her death in 1955, they separated in the mid-1930’s.) More than any other of his portraits, this picture stands at the center of controversy over his relations with women and the meaning of portraiture in his art. Almost immediately after it was painted, and continuing up to the current day, critics have condemned the painting as a bourgeois confection, a descent from the mountaintop of Cubism to the dry gulch of Classicism. Several critics have even identified the cause of this collapse: Olga herself. Long before Mailer found a scapegoat in Eva, antagonistic writers blamed Olga’s supposedly proper manners and domineering personality for Picasso’s apparent turn from the high road of the avant-garde. 13. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Olga was no Victorian; she was an extremely adventurous woman who had left her native Russia to join the most innovative ballet company in the world – Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes – and was already a respected member of the troupe by the time she met Picasso. Moreover, Picasso had begun making classical portraits two years before he even met Olga, because he wanted a break from a Cubism that had become so popular it seemed to constitute a new academy. In the early years, their union was a perfect blend of modernism and high life; Olga’s sophistication and prominent friends provided Picasso with the platform he needed to shift from bohemia to the beaux quartiers. At this time, he also formed an alliance with the famous dealers Paul Rosenberg and Georges Wildenstein that placed his work in the august circle of Corot, Courbet, and Renoir – a bit as if he were a young artist joining Pace-Wildenstein today. The magnificent portrait of Olga reflects these new circumstances and shared ambitions. Without forgetting the lessons of Cubism, Picasso painted a mastery homage to Ingres, one that he believed would get him and Olga into the Louvre. 14. Yet by the mid-1920’s, Picasso had tired of high society, the fittings for Savile Row suits, and nights at the theater. Already in his mid-forties, he wanted rejuvenation, and Olga became the whipping post, so much so that her granddaughter, Marina Picasso, has published a book, Les enfants du bout du monde (Children at the End of the World) that seeks to restore Olga’s reputation as a generous and sympathetic person. Within a few years, Olga is shown in paintings such as Bust of a Woman with Self-Portrait as a spike-tongued, screaming harpy who threatens both Picasso and his art (the painted profile hanging on the wall). She probably did scream, since by 1926 Picasso had met Marie-Therese Water, a sixteen-year-old who would soon be his mistress. 15. For many of us, the Marie-Therese suite constitutes the high point of Picasso’s portraiture. These paintings are by far the most vibrant images, filled with physical metamorphosis and thematic allusions – as well as throbbing sexuality. In one case, Still Life on a Pedestal Table, Picasso’s somersaulting imagination transforms Marie- Painted Ladies / 5 160 165 170 175 180 185 190 195 200 Therese’s nubile body into a curvaceous pitcher and overflowing bowl of fruit. Even the repressive superego of current gender studies cannot make us dismiss these pictures’ power. Yet their success demonstrates how anomalous Picasso’s portraits are. After all, how could a relatively naïve adolescent be the subject of great portraits? 16. Because they are far more than portraits of Marie-Therese. No doubt reveling in his dominance of this girl, Picasso nonetheless kept his mind focused on the most important new initiative in the art world, the Surrealists’ uninhibited devotion to the unconscious, especially their pursuit of overwhelming love, l’amour fou, supplies the current that is channeled through the body of Marie-Therese. Of equal importance to these paintings (can we really call them “portraits” any longer?) is the Surrealists’ desire to make their deepest fantasies public. At least eight of the Marie-Therese paintings in the exhibition, one quarter of the total, were painted in 1932, and they were made for display in the first museum-style exhibition of Picasso’s work at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris. 17. In a sense Picasso painted these portraits to make the affair public (which they did, much to Olga’s fury), yet they are really more about Picasso’s relationship with art than about his fling with Marie-Therese. Picasso easily presented himself as more liberated than any of the Surrealists, but he also outdid a far more threatening rival – Henri Matisse, who had held a retrospective in the same rooms one year earlier. In paintings such as Nude Asleep in a Landscape, Picasso grabbed Matisse’s luminous palette and commanded his lounging odalisques to perform according to the dictates of the Marquis de Sade. Yet in masterpieces such as The Dream or Girl Before a Mirror, Picasso also created riveting images of psychological introspection that move far beyond the vessel of Marie-Therese. 18. In contrast to her immaturity, the next two women in Picasso’s life were artists in their own right; they challenged his view of them with their own self-images. Although chiefly characterized these days as the Weeping Woman, Dora Maar was far from the hysterical female this label implies. By the time Picasso met her in the mid1930’s, she had established herself as an important Surrealist photographer and a person of strong political conscience. As Fascism swept across Europe, she opposed it in Germany and then in Spain, where her loathing for Franco brought her in unison with Picasso. Not only did she encourage him to make Guernica as a protest against the Spanish Civil War, but she located the Grands-Augustins studio where he composed it, and even helped paint the giant mural. In her own art, the bizarre creatures and jarring distortions of her contemporaneous photomontages register her disgust at events. Despite the fractious life Picasso and Dora shared, his portraits of her primarily reflect their commitment to others: The tears she shed are ones of outrage over world events far more than mere private quarrels. The personal has become political. 19. Picasso’s relationship with Francoise Gilot was unique. Although she was 41 years his junior when they met during World War II, she managed a considerable Painted Ladies / 6 205 210 215 220 225 230 235 240 degree of independence during the nearly ten years they spent together, and was the only one of Picasso’s longtime lovers who left him, rather than suffer rejection. (Her 1964 book Life with Picasso remains one of the most insightful accounts of his art and personality.) Probably because of this self-possession, Francoise frequently stood apart from Picasso’s art. She was never as fully absorbed into his concerns as were her predecessors, although his portraits would not acknowledge her own diligent activity as an artist until their breakup had begun. This difference can be gauged in Picasso’s greatest portrait of Francoise, Woman-Flower. The metaphor suggests his earlier portrayals of a docile Marie-Therese, but Francoise’s ramrod posture and blazing eyes evoke a very different presence: a person of self-assurance, intelligence, and grace. 20. How did she escape being mauled by a man she calls a “sacred Monster”? “I always had my own identity,” she says, adding that Marie-Therese “was a woman with psychological problems” and Dora Maar was “fairly masochistic. Picasso cannot be held responsible. If they had some moral fiber and strength, it would not have happened.” 21. According to Gilot, being painted by Picasso could cast a Dorian Gray-like curse. “The reason some of those women could not disengage from him was that he had understood and expressed their personality so well that they were entirely dependent on him for being who they were. They glorified themselves through the portraits. It’s a dangerous thing if your existence is linked to an object or icon. In a way, it’s as if they jumped into the painting.” Gilot staunchly refused to be drawn in. “I liked the portraits of me he did as paintings, but I didn’t identify myself with them,” she says. “And,” she adds with a certain pride, “you don’t find the portraits of me with two eyes on one side of the face.” 22. Picasso met Jacqueline Roque, his second wife, in the mid-1950’s, at the pottery factory where she worked and he made the ceramics that occupied much of his later career. (They married in 1961.) Jacqueline quickly made herself indispensable, so smoothly assuming the burdensome roles of secretary, greeter, and studio assistant that he could detach himself from quotidian concerns more than ever. In his paintings, she sometimes appears as a silent presence, watching the artist at work in his studio. Jacqueline accompanied Picasso on his further retreat into meditations of past art and his place in history. She merged seamlessly with his variations on nineteenth-century masterpieces, becoming an odalisque in Delacroix’s Women of Algiers or a reclining nude in Manet’s Dejeuner sur L’Herbe. 23. Jacqueline did not end her duties with Picasso’s death in 1973. As his primary heir, she struggled to perpetuate his legacy. But the responsibilities proved too great, and in 1986 she shot herself. Nine years earlier, Marie-Therese had hanged herself. Olga died on the verge of madness. These women’s devotion to Picasso was overwhelming. But he viewed things very differently. Painted Ladies / 7 245 250 255 260 265 24. Decades earlier, Picasso had referred to Velasquez in making his most revealing statement about portraiture – and about the relationship of art and life. Citing the great Spanish artist’s portraits of King Philip IV, Picasso dismissed the notion that his predecessor had subordinated his art to simply recording the man. After all, Peter Paul Rubens’s portraits of the same king seemed to show an entirely different person. No, Velasquez had invented his own image of the king, and he “convinces us by his right of might.” As Picasso saw it, these pictures were really about Velasquez’s personality – not the king’s. 25. In a fundamental sense, all of Picasso’s portraits are self-portraits. (For purists, the exhibition does include a fine group of strict self-images that spans the artist’s career.) But Picasso did not create in isolation. He required contact with the world to spark his creativity: sometimes a creased newspaper, or a chipped pipe, or a desiccated skull, but most powerfully a human being – especially someone he knew intimately. Then Picasso’s plenteous imagination funneled into that person, morphed itself into an amalgam of the two, and returned as a painted image that represents no one – yet may address us all. Probably because they resisted this invasion, few men appear in Picasso’s major portraits. Women were his primary subjects, or, better, objects of portraiture. 26. This artistic dominance of women is troubling to many of us, particularly because it often parallels the events of his life. As his partners, these women were more profoundly bonded with him than any men. Perhaps that well of knowledge was necessary to churn the depths of Picasso’s imagination and enable him to speak through them of social roles, psychological turmoil, and the inhumanity of war. Yet Picasso never lost himself in others. As with Velasquez, his “might” always won out. If this interpretation of Picasso’s portraiture does not entirely satisfy our sympathy for these women, perhaps we should accept his mother’s frank judgment: “He’s available for himself but for no one else.” When it comes to his art, are we really sorry?