The Lost Sheep - Blackburn Cathedral

advertisement

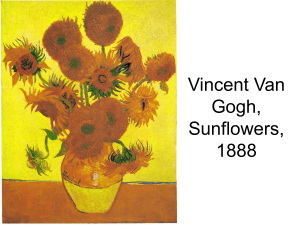

The Lost Sheep Luke 15:1-10 May the words of our mouths and the meditations of all our hearts always be acceptable to you oh Lord. Over the last few weeks I attempted to disappear for a few hours a day. I wasn’t lost, but I did want to be somewhere different for awhile preferably warm. I went to Florida to visit my Mother and to watch the waves. I also contemplated the genius that was Picasso and thought about being lost. What you might ask do these three things have in common? Quite a lot I discovered. God is not content with the majority. God does not rest when a job is almost completed nor does God seem to mind that finding the lost is a never ending task. As I stood listening and watching the waves pounding the shore in a constant motion, I asked myself in what manner were they created and where do they go once spent? Endless waves, endless masses of people. How can God find me? How can I manage not to get lost in the crowd only to be forgotten and then all alone? “Which one of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness and go after the one that is lost until he finds it?” Of course human souls are more significant than ocean waves, yet human souls do get lost in many ways. In the past, I have had the privilege of teaching many students from the Anglican Communion. At one point during a course I was 1 teaching in Canterbury there were students from 14 different countries: South Africa, the USA, Hong Kong, India, Canada, Malaysia, the Sudan, The Gambia, Liberia, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Nigeria, Pakistan and Armenia. The reason for listing the countries is to illustrate how much of the world is distant to us or even lost. How much of what we know of these countries is through television and the news – oftentimes through tragedy? We primarily define ourselves and our world by what we see and know around us, yet to glimpse the composition of God we must search the invisible and contemplate the unknown. The gift of being exposed to these students was to learn their own stories rather than a distant, nameless face in a crowd in the news. Samuel was from the Sudan. He was a serious, yet elegant gentleman in his early 50’s. It was only after the first week was over that I discovered that he was a refugee living in Uganda and, when leaving the country to come to the UK, had had his passport stamped, ‘unwelcome to return’. There was Priscilla from the Gambia who was married to the Bp of the Gambia. Priscilla was the first woman to be ordained a priest in that country and when she celebrated our early morning Eucharist you could sense the strength and legitimacy of an African woman priest. There was also young Shanna from the Church in South India. Shanna was a young seminarian who was working on a project to care for people who are living in the forest. These people are beyond the pale, beyond even the untouchables abandoned, forgotten and lost. To have the luxury to broaden our knowledge, to see beyond our own lives is a great blessing. There is much to be thankful for in the Anglican Communion. 2 Returning to the ocean, the tides, the moon, and the creator combine to take account of each wave and we need not concern ourselves too much. People are a different story. There was once a time when people could live in almost isolation. For example, only a hundred and fifty years ago a farmer and his wife could be almost selfsufficient. Events in his village constituted his entire life. The rest of the country, much less the world made little or no impact on his daily life. This is no longer true. Industrialisation and technology in the 20th century changed the landscape forever. And this brings me to Picasso. Picasso is one of my favourite artists and I have had the great joy of visiting both museums dedicated to his art in Malaga and Paris. Picasso was born in 1881 in Malaga. He was just 19 when the new century began and in 1900 he was living in Paris. Picasso was a genius not because he was a great painter – he was. Picasso was a genius not because he could work in many mediums - he could. He was a genius because he dared to attempt to depict reality as it really was in its entirety. Much of his art is unattractive, but reality at times can be unattractive. Picasso’s first great contribution was Cubism. Cubism takes the elements of a scene, face or landscape and blocks sections off and then puts them together again in a kind of collage, thus graphically illustrating each element’s equality. A nose is no more important than an arm or the branch of a tree no more so than a cloud. You may not like Picasso’s work – many don’t. You may claim that his pictures are strange, crazy even. Yet, herein lay his 3 genius. Picasso wanted to show that everything had its place and should be given importance. He knew that what we see at any given moment depends on light, how we feel and the angle, but each section whether we see it with equal clarity is equally important. Picasso showed us that our reality is not always a pretty, pastoral landscape with the shadows enhanced with a perfect light as the Victorians idealised. The Twentieth century has brought a harsh reality where bombs in Dunkirk or chemical weapons in Syria, famines, floods and tornados have a direct effect on our lives. God knows the interrelatedness of creation and the value of each part. That is why God will search out every last soul. Every last one. Much of the time painters try to fill in the empty spaces with an illusion of an alternative reality. Picasso did not. He painted reality as it was – even those bits which were ugly. However, we are urged to move closer to a more beautiful world. A world God is urging us towards, where nothing is hidden or lost. One of the encouraging outcomes of learning about the other and the positive activities of those in other parts of the world is the significance of common knowledge and support. In today’s world it is easier to have an understanding of a place distant from our own lives. As a result, such understanding allows us to improve the current reality. Searching out and finding means we can change the fate of the lost. The more we can understand the pains, joys, triumphs and sorrows of the other means we can really care for each other. God’s world can sometimes be a Cubist painting, disjointed and boxed off. Yet, we 4 can also see the world as a glorious tapestry interwoven and interconnected illustrating the grandeur of God. The lost is what we cannot see or will not acknowledge whether in a distant land or hidden in our own lives. All of it will be redeemed – every last bit of it. No one part of creation has precedence over another and now more than at any other time in history what one part of the world does effects the rest whether in the realm of politics or the environment. God is moving us closer to a deeper knowledge of the divine. This must start with a wider knowledge of creation with the same urgency to find and save the lost. “Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep that was lost.” God knows every hair on our head, every wave in the ocean, God knows the significance of every segment of creation and will not rest until every single soul is acknowledged and saved and then there will be joy in heaven indeed. Amen 5