A:\brett`sstuff\Porter4.wpd() Page 1 Why the “Creamy Layer” Should

advertisement

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 1

Why the “Creamy Layer” Should Not Be Excluded from Affirmative Action Programs:

An Essay on Leadership and Responsibility in Social and Political Context

Aaron Porter

Assistant Professor

Department of Sociology

University of Illinois

What can India learn from the U.S.’s affirmative action dilemma -- in particular the

concern over whether middle class people should receive affirmative-action opportunities? This

concern deals with what Indian courts have described as the “creamy-layer” issue, that is,

whether or not unfair opportunities are operating in favor of members of oppressed groups who

have improved their socio-economic status positions as a consequence of affirmative action

initiatives. This essay critically assesses the Indian concerns over the creamy-layer group in light

of the American experience, drawing in particular on the life and work of W.E.B. DuBois.1

India’s historical system of social stratification has been of intense interest to sociologists

from the very beginning of the discipline. Max Weber wrote at length about how caste groups

were organized and separated based on hierarchical rules of ritual purity.2 Weber noted that the

system was an example of how social rankings are based on prestige and ethnic group

orientations. Weber contended that India’s rigid stratification system operated with closure-like

manifestations in the way upper tier caste groups maintained their social positions and power in

1

This essay is prompted by my participation in the 1997 conference, Rethinking Equality in the

Global Society, which was hosted by Washington University and brought together legal scholars

and social scientists from India, South African and the U.S., and by a subsequent course I taught,

Global Equality in Affirmative Action Context. The graduate-level seminar based course is a

systematic study of the evolution and socio-political consequences of affirmative action policy

on the social fabric in the United States, India, and South Africa. The legal, historical, and

cultural roots of affirmative action policy through a cross national and cross cultural approach

serves as a comparative basis for understanding the real from the obtuse issues that surround

such polices with an eye toward improving by broadening the debate and public policies on

affirmative action. The course is the first of its kind at the University of Illinois, and perhaps the

first course of its kind in the U.S. Although the focus of this essay is on possible lessons India

might learn from the American experience, I also believe there is much the U.S. can learn from

India and South Africa. For example, since conversations about race and affirmative action in

the U.S. create social tensions, looking at India broadens the current debate because race is not

the key factor there. India’s Mandal Commission used non-threatening variables — including

historical oppression and other social phenomena that impeded or limited the opportunities for

particular groups — as ways to categorize the groups receiving affirmative action benefits. (See

____ for further discussion of the Mandal Commission.) This neutral approach is particularly

useful to the U.S. given the tension around race related issues, and especially the question about

who should receive affirmative action.

For an overview of India’s social stratification and religious system, see Max Weber, The

Religion of India. Glencoe: The Free Press, 1958.

2

1

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 2

the political economy of the country by maximizing their own advantage. For example, limiting

the market place and positions of social prestige from lower caste groups was accomplished by

restricting their access. These structures of oppression also reflect, as Marx would contend,

ideological beliefs regarding the social position of individuals in that society. For example, Marx

and Engels’s view of ideology is reflected in what they call the superstructure of society which is

determined by the economic material base. Since lower caste groups do not control the means of

production, the relations of production are determined through the social relations or social order

of that society, and the legal, political, and social consciousness of the society is given context as

material life shapes “ideological forms in which men become conscious.”3 Ideological beliefs

gives character to the social and political processes of life, maintaining a social system through

social stigmas that reflect the perceived social place or class position of particular groups. The

maintenance of this system of closure was through the segregation of ethnic groups, in addition

to laws, customs, and a social fabric which discriminated against lower caste groups in areas of

occupational specialization and economic opportunities.

In the 20th century a number of strategies have been employed to alter this system.

Upon achieving independence in 1950, the central government led by Nehru began to expand the

economy by building large factories for the production of iron, steel, and other products. These

kinds of improvements in the economy and the country’s infrastructure in particular especially

in the area of science and technology strengthened the job base, improved mass areas of poverty,

illiteracy, and ignorance, so that members of lower caste groups could participate not only in

employment, but also the political economy of the country.4 This expanded role of government

as employer related directly to a second strategy, reservation of jobs for “backward classes.

In 1870, South India introduced reservations for backward classes or castes. By 1920,

however, reservations had became a feature of public life in South India, but not throughout the

entire country. Extensive debates in the Constituent Assembly that drafted the constitution for

independent India led to constitutional language authorizing the use of quotas to advance

opportunities for members of scheduled castes (the former “untouchables”) and other “backward

classes.” Since the government was the major employer in the first decades of independence, the

life chances for these groups have increased through opportunities in government, the judiciary,

and public corporations controlled by the government.5 This progress does not necessarily mean

that similar progress has been made in private industry. Nonetheless, India’s affirmative action

advancements may seem bold to some. In fact, such practices in the U.S. would be viewed as

radical, especially the explicit use of quotas across a broad range of employment.

One of the major concerns, however, in the use of affirmative action or reservations was

the creamy layer group in India. In November of 1992, in what is known as the Mandal

Judgment, the Supreme Court of India affirmed the use of caste as a factor in determining

3

See preface, by C. Wright Mills, The Marxists (New York: Dell press, 1966), p. 43.

4

M.N. Srinivas, “Caste: A Systematic Change.” unpublished manuscript, p. 1-3.

5

Ibid.

2

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 3

eligibility for affirmative action, but excluded the creamy layer among the backward classes

from eligibility for reservations.

[The proposal of ] of an income limit, for the purpose of excluding persons (from

the backward classes) whose income is above the said limit ... is very often

referred to as “the creamy layer” argument. Petitioners submit that some

members of the designated backward classes are highly advanced socially as well

as economically and educationally. It is submitted that they ...[are] as forward as

any other forward class member -- and that they are lapping up all the benefits of

reservations meant for that class, without allowing the benefits to reach the truly

backward members of that class. ...[W]e feel that exclusion of such socially

advanced members will make the ‘class’ a truly backward class and would more

appropriately serve the purpose and object [of the constitution]. ...[W]e direct

the Government of India to specify the basis of exclusion -- whether on the basis

of income, extent of holding [property] or otherwise -- of [the] ‘creamy layer’. ...

On such specification persons falling within the net of [this] exclusionary rule

shall cease to be members of the Other Backward Classes.6

The aspect of the Mandal decision has evoked strong opposition from leaders of

the backward class groups. In fact, one state legislature, in Kerala, passed a

resolution denying the existence of creamy-layers among the OBC’s in that state.7

The “creamy layer” debate in India resembles the argument now frequently made in the

U.S. that since America has radically increased opportunities for people of color and women in

political, economic, and educational institutions over the past three decades, affirmative action

programs are no longer necessary. The logic is that since affirmative action programs have

improved the life chances for minority groups and women, especially those who are now in

middle to upper classes, such programs should not favor them.8 It is thought that such programs

should be geared toward the less fortunate, poor individuals, or in essence the “more deserving.”

Its central claim is that socio-economic factors ought to be the measuring stick for who should

have access to affirmative action.9

6

Opinion of Justice Reddy, paragraph 86, pp. 294, 396.

Srinivas, “The Pangs of Change: India democracy is a secular miracle of the modern world, but

the quality of our democracy is poor.” Frontline, 22 August 1997, p. 68

7

8

The advancements of minorities in terms of increased opportunities in the wider society are

based on a number of reports. See for example: J.P. Smith and F.R, Welch. Closing the Gap:

Forty Years of Economic Progress for Blacks. (Rand Corporation, 1986), and Gerald D. Jaynes

and Robin Williams, Jr., eds. A Common Destiny: Blacks and American Society. (National

Academy Press, 1989).

9

In regards to South Africa, publications such as the Economist and various articles have

claimed there is a growing polarization between the small, new black bourgeoisie class and the

poor. {Citations needed.} However, there is no data or research on South Africa with a scholarly

discussion of the impact of affirmative action policy in expanding and creating a creamy layer

3

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 4

The argument that affirmative action benefits for creamy-layer groups are no longer

needed is problematic on at least three counts. First, like affirmative action in the U.S.,

reservation policy in India creates opportunities for talented individuals by drawing them from

lower caste groups. They become participants in the local and federal government, judiciary, and

businesses controlled by the government in a way that meets the goals set forth in India’s

constitution. The experience in the U.S. shows the critical role to be played by a leadership

class drawn from an oppressed community. The civil rights movement reflects the very best

that the U.S. had to offer in terms of blacks fighting for access to opportunity. Martin Luther

King, Jr. and Charles Hamilton Houston came from privileged backgrounds, and black college

students from across the country who fought for poor blacks in the South regarding their civil

right to vote are critical examples of how blacks have given back to their indigenous

communities in terms of access issues.10 It was such members of the “creamy-layer” who fought

for access even though they also benefitted from such gains. One should not take for granted

the continued supply of such leaders. If India has glass ceilings for talented women and

minorities like that in the U.S., then one must consider whether or not there are sufficient

numbers even from the creamy-layer group in positions of power to help or to secure

institutional access for others by creating or maintaining equality of opportunity.11 This is one

effect in terms of black participation in the business economy of the country. There is some

discussion and a short chapter on affirmative action regarding the coloured community in

Wilmot James, Daira Caliguire and Kerry Cullinan's book, Now That We are Free (1996). This

work is not quite accurate regarding black South Africa’s position today regarding this group

having significant positions that affect opportunities in the economy and social structure

particularly at the lower community level. In terms of this issue surrounding the creamy-layer,

Anthony Marx's new 1998 book, Making Race and Nation, compares the US, South Africa, and

Brazil, but only barely gets up to 1990, but offers no real substance regarding black advancement

through affirmative action policies. And there isn't any real data for the Mandela era except for

some journalistic articles.

10

For a detailed account of how Charles Hamilton Houston contributed to black access to the

wider society, see the essay by Robert Carter, “In Tribute: Charles Hamilton Houston.” Harvard

Law Review, vol. 111, no. 8, June, 1998.

11

For an account of the importance of black professionals being in a position to make a

professional community pluralistic, see Aaron Porter, “Norris, Schmidt, Green, Harris, and

Higginbotham and Associates: The Sociolegal Import of Philadelphia Cause Lawyers” in Austin

Sarat and Stuart Scheingold, (eds), Cause Lawyering: Political Commitments and Professional

Responsibilities (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp151-180. As minority,

“creamy-layer” senior people retire from their positions, institutional access for others from

oppressed groups start to decrease. This is the primary concern in the U.S. as noted with recent

American Bar Association and the National Bar Association reports, and speaks to the import of

affirmative action as a way to stabilize people of color in professional positions. The question is

not one of talent or skills, but of access. See Miles to Go: Progress of Minorities in the Legal

Profession (Chicago: Report of the American Bar Association, 1998).

4

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 5

reason why the stabilization of middle and upper-classes are important in terms of affirmative

action. Continuing to help disadvantaged groups increase their opportunities in the larger social,

political, and economic system can also serve as a way to keep the system honest. In other

words, being a watch dog is a great public service, rooted in a rich democratic tradition. That is,

when the majority party is in positions of power, in a democratic society, the minority party is

allowed representatives in the system to maintain a level of fairness by being a watchdog, even if

that means fighting for their interest.

Second, entry into the political, educational, and social systems must be maintained and

stabilized in order to insure that traditionally under represented groups become a significant part

of the larger economic and political fabric. Just because adults in creamy-layer groups might

advance their status positions does not mean that their children will not experience patterns of

discrimination. A few decades of affirmative action do not negate centuries of discrimination

nor make a serious dent in the means of production or political economy. Reservation or

affirmative action programs do not quickly destabilize the power of members in dominant

groups, alter the balance of power in organizations or institutions, or resolve larger patterns or

structural forms of social and economic inequality especially regarding the means of production.

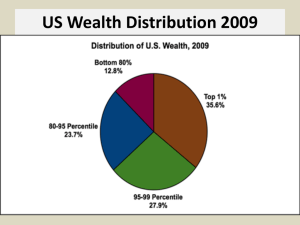

Historical data reveals how white groups in the U.S. were able to stabilize and maintain

their advantageous middle class status through decades of discriminatory practices that worked

in their favor. Some whites even argue that their positions today are based entirely on “merit”

which they claim is the key component for individual and familial success. However, most

whites do not realize how the extraordinary oppression of African Americans in the past and the

privileges of the ancestors of today's white families are interconnected. They also do not realize

nor see how these earlier privileges have been inherited and translated into indicators of "merit."

Kenneth Smallwood has noted that white America benefitted from huge federal

"affirmative action" plans for whites only. Such programs laid the foundation for much white

prosperity and African American inferiority in resources and opportunities in the modern U.S.12

One important example illustrates this point. Because of racial caste relations in the U.S.

especially from the 1860s to the early 1900s, the Homestead Act provided free land in western

areas for white families; but, because most African Americans were still in the semi-slavery

peonage of southern agriculture, they could not participate in this government "affirmative

action" program of giving land. Significantly, that billion dollar land giveaway program became

the basis of economic prosperity for many white Americans and their descendants. Furthermore,

numerous railroad corporations emerging in the 19th century got their start in huge giveaways of

federal lands, plus hundreds of millions in cash, all to assist private white enterprise. In another

example, most New Deal programs in the 1930s disproportionately subsidized white Americans

and white controlled corporations. The policies of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA)

helped millions of white American families secure housing while until the 1960s that same

agency's policies encouraged the segregation of African Americans in ghettoized communities.

12

. Kenneth W. Smallwood, "The Folklore of Preferential Treatment," Southfield, Michigan,

Unpublished manuscript, 1985.

5

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 6

Massive New Deal agricultural programs and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation kept many

white bankers, farmers, and corporate executives in business, providing the basis for postwar

prosperity for white Americans. Similarly, massive aid programs have never been made available

to African Americans. Even with the many advances in the educational and economic

opportunities of middle class blacks, housing, income inequality, and other forms of racial

derogation in integrated professional environments continue to reflect segregation and

discriminatory practices.13

Third, there should be caution in assuming that new status positions for members of

lower castes will fully increase their class positions and negate social stigmas. A powerful

illustration comes from the life and work of the African American intellectual, W.E.B. DuBois.

In the Souls of Black Folk, DuBois articulated the problem of racial stigma and identity in terms

of how blacks are perceived by whites in ways that affect their meaningful participation in the

wider society. DuBois stated:

Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by

some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly

framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant

sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, then instead of saying directly,

How does it feel to be a problem? They say, I know an excellent colored man in

my town.... To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer

seldom a word.14

DuBois graduated from Fisk University, an all-black Congregational school in Nashville,

Tennessee, where he learned much about white society. DuBois’s image of himself when he

arrived at Fisk sheds important light into race relations as sociologist Elijah Anderson writes in

the introduction of DuBois’s work, The Philadelphia Negro. Although DuBois was “the son of a

servant and had little money of his own,” he had been socialized through his early education in

the prosperous mill town in Massachusetts’s Berkshire Mountains and his familiarity with

upper-class people to think of himself as part of the elite. Anderson adds, “He certainly felt

himself to be far removed from the often destitute, illiterate blacks he encountered in his noble

efforts to teach members of the local black community. The idea that anyone would consider him

a part of that society, merely on the basis of his skin color, had not previously occurred to him. It

was this introduction to life in the South that taught DuBois about racism” or in part what it truly

meant to be black in America.15

13

See the respective works by Douglas S. Massey and Nancy Denton, American Apartheid

(Cambridge, MASS: Harvard University Press, 1993); Andrew Hacker, Two Nations: Black and

White, Separate, Hostile and Unequal (New York: Ballantime Press, 1995); and Joe Feagin and

Melvin Sikes, Living With Racism: The Middle Class Experience (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994).

14

W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk. (New York: Signet Classic Printing, 1982). pp.

43-44.

See Elijah Anderson’s introduction to DuBois’s work, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social

Study (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996). pp. x-xii. For a detailed analysis of

15

6

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 7

At Fisk, DuBois discovered the “rich diversity of the black race” as an undergraduate

student before going on to Harvard and traveling overseas to Germany where he studied with

Max Weber, among others. DuBois would later finish his Ph.D. and graduate from Harvard

University. His job hunt would also turn out to be an education in American race relations

because no white college was interested in hiring him as a junior professor even with his strong

credentials. DuBois’s early life reflects a period best described as racial caste and white

domination. His scholarly writings nonetheless provide insight into an American dilemma.

To know an excellent colored man is to view this individual as an exception while

affirming what others think of the group at large from which he comes. This individual is at first

thought to be an exception to the general rule in how social stigma or racist views impact on the

larger group. What DuBois articulated and illustrated in his own life was that the general pattern

of social stigma and race discrimination will follow as well those “excellent colored

individuals.”16

Racial stigma continues today. Many talented blacks have reached high levels of status

attainments, but race still plays a key role in how they and their children are defined and

perceived. Thurgood Marshall is still known as a black supreme court justice. The late A. Leon

Higginbotham is still known as the outstanding black legal scholar and federal judge. Even

prominent black business people are limited in terms of how far they succeed as Ellis Cose

describes in the Rage of the Privileged Class.17 Even though the children of this class will have

opportunities in the wider society, this does not necessarily mean that they will be treated any

DuBois’s life, see DuBois, Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race

Concept (New York: Schocken, 1968); and, David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. DuBois: Biography

of a Race, 1868-1919 (New York: Henry Holt, 1993).

16

George Fredrickson, for instance, in The Black Image in the White Mind, investigates this

DuBoisian notion by illustrating how racist thoughts among white elites including the clergy,

physicians, intellectuals, business leaders, and other professionals were consolidated in the U.S.

social structure in the 19th and 20th centuries. This image affects not only what whites think, but

also serves as a basis for black limitation in the socio-economic and political economy. See

Fredrickson, The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and

Destiny, 1817-1914. (Wesleyan University Press, 1971). Pop artist Stevie Wonder puts it simply

by saying that minorities cannot cash-in their face. Christopher Edley in Not All Black and

White: Affirmative Action and American Values (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996; preface p.

xiii) broadens DuBois’s concept, noting that the “exception syndrome” or that “some of my best

friends are Negroes” is an expression that whites often use while establishing their fides on racial

matters. As Edley contends, “in the exception syndrome, one can hold on to a prejudice about a

group and treat individual counterexamples as mere exceptions to the rule.” If one pushes

Edley’s conception to its logical conclusion, then one gets back to DuBois’s original thought and

how social stigmas affect the group irrespective of social status.

17

See generally Ellis Cose, The Rage of a Privileged Class (New York: Harper Collins, 1993).

7

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 8

better or live without racial prejudice, social stigmas and their consequences.18 David Shipler’s

survey reveals how whites continue to view blacks as inferior (53.2% felt that blacks were less

intelligent), as not working as hard as whites (62% view black workers as working less hard that

others), and as living on welfare (77%).19 Upper class blacks continue to face this reality. For

example, General Motors instituted an affirmative action program to improve minority-owned

dealerships. This group was highly educated, wealthy, and trained in the successful operation of

car dealerships under GM executives and the like. Because of white resentment and how they

viewed black advancement, each person not only failed but was put on a specific course for

failure based on race. After completing the program, blacks were given dealerships in locations

that GM realized had a history of failure.20

The concern over creamy layers is, at best, a diversion away from the more serious issue

regarding the way race or caste stigma affects a group as they are defined by elites or

representatives of the dominant culture. Color and caste prejudice affects middle and upper-class

groups in the U.S. as noted above. The U.S. situation provides a basis or window for showing how

similar groups abroad might be treated as they increase their opportunities in the wider society,

especially creamy-layer groups.

18

See, for example, the work by Charles Tilly, Durable Inequality (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1998), chapter-one.

19

See generally David K. Shipler, A Country of Strangers: Blacks and Whites in America (New

York: Knopf, 1997).

For details, see ABC News Night-line manuscript for the program, “Good Intentions.” 2 June

1998. ABC Transcript #4441, pp. 2-9

20

8

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 9

Leslie Carr in Color-Blind Racism uses a Marxist perspective in order to provide insight

into how inequality persists. Carr claims that the foundation of the U.S. society was based on

capitalistic interests and maintaining that interest through the means of production can operate

simultaneously with a societal superstructure which uses racist ideologies that perpetuate

inequality. Carr notes that people respond to economic forces or “the mode of production of

material life” and describes how social behavior, law, and policy are rooted in that base.21 The

control by whites of the dominant culture relates to the way racist ideology and racial inequality

emerged as Oliver Cox avers to in his work.22 Color-blindness, Carr contends, “is not opposite of

racism, it is another form of racism”;23 this ideology has a way of mystifying the world by hiding,

denying, and inverting contradictions. Carr adds that this ideology “sublimates, diverting energy

into socially acceptable substitutes for real transformations. It solves contradictions in imagination

that cannot be solved in the real world. In these ways, ideology preserves inequality and protects

the primary contradictions in the base of society and thus serves the ruling class.”2421. See Leslie

G. Carr, Color-Blind Racism, pp. 9-11. As civil rights legislation and affirmative action directives

helped increase the opportunities for minorities and women in U.S. institutions, the abstract idea of

capitalistic economic advancement gave rise to the ideology that every individual can achieve the

American dream.25 The further belief is that these advancements for minorities and women in

particular occurred in a race or gender neutral way and that inequality does not exist for these

groups particularly in classes of the creamy-layer. Carr asserts that this abstract ideological view is

21

Leslie G. Carr, Color-Blind Racism (Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication, 1997). pp. 1-3.

22

See generally, Oliver Cox, Caste, Class, and Race: A Study in Social Dynamics (Doubleday,

1948.)

23

See Leslie Carr, Color-Blind Racism, p. x.

24

Ibid., p.5

Assimilation theories which include the hope for black inclusion in the U.S. society are pointed

25

This ideology was forecast by the assimilation theories developed by influential early

sociologists. out in the works by Milton M. Gordon, Assimilation in American Life: The Role of

Race, Religion, and National Origins (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964); Nathan Glazer,

Affirmative Discrimination: Ethnic Inequality and Public Policy (New York: Basic Books, 1975.

Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, 2 vols.,

(Harper and Brothers, 1944). For a critical view of such assimilation theories, see Joe Feagin and

Aaron Porter, “White Racism,” Choice (February, 1996, pp. 903-914). Also note that because of

social stigma and racial discrimination, Nathan Glazer pulls back from his original thoughts on

assimilation theory after recognizing the unique experience of African Americans. See for example

Glazer’s work in We Are All Multiculturalists Now (Cambridge, MASS: Harvard University Press,

1997, pp. 96-146.

9

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 10

an exact inversion of social reality as the U.S. model reveals above.26 Race discrimination still

permeates the American society and affects the experiences of creamy-layer groups in the U.S.

The use of color-blindness reflects a sub-component of how a larger racist dynamic operates in the

social fabric.

Even though constitutional law and oversight agencies in India have made great strides

toward altering unfairness and increasing the opportunities for disadvantaged caste groups, if a

comparable notion of caste neutrality sinks into the social fabric of Indian society, then it is

possible for this perception to be an inversion of reality. Inequality can persist behind a caste-free

or color-neutral society. Under this societal illusion, members of creamy-layer groups will not only

be limited in the way that affirmative action can help this group, but also continue to suffer the

effects that social stigmas have on racial or caste identities.

26

Ibid., p. 9-11.

10

533574484(March 3, 2016) Page 11

Endnotes:

11