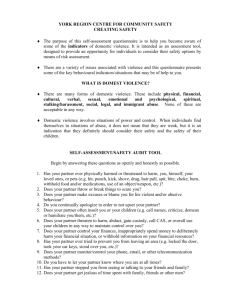

Understanding Sexual Violence - Minnesota Center Against

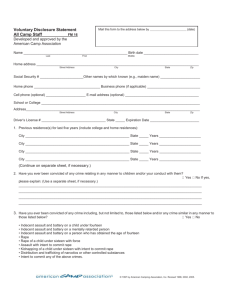

advertisement