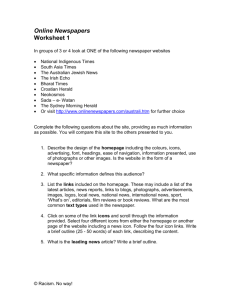

MLK, Jr

advertisement