the career of an Asheville graffiti artist

advertisement

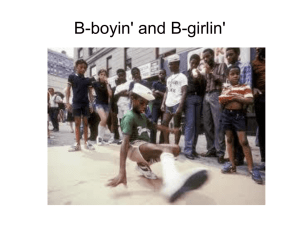

Process Over Product: the career of an Asheville graffiti artist David Nosse 05.12.08 Abstract This research explores the role graffiti plays and has played in the lives’ of its creators. Using Howard Becker’s concept of a deviant career as framework, this essay interprets the issues of motivation and identity as they play out during a career in graffiti. Information was collected through formal interviews with six Asheville graffiti artists. This research challenges existing ideas surrounding graffiti as a means of attaining symbolic capital, instead suggesting that graffiti subculture is oriented toward community involvement and the attainment of fun, with the process (all aspects leading to the completion of a piece of graffiti) rather than the product (tangible piece of graffiti) providing the ultimate motivation. Title photo: The “Ice House,” a popular canvas for Asheville graffiti artists 2 Table of Contents Introduction Through the Eyes of an Artist……………………………………4 Classification……………………………………………………..5 Career…………………………………………………………….8 Methods…………………………………………………………..10 The Graffiti Career Early Stages………………………………………………………13 Multiple short-term Engagements………………………………..17 Progression……………………………………………………….20 Community Affect………………………………………………..24 Conclusion Motivation and Identity…………………………………………...26 References………………………………………………………...28 3 In urban areas we see it nearly everyday of our lives, under bridges, on lampposts, on billboards, or on train carriages. Graffiti is an undeniable feature of any American city. Yet relatively little is known about graffiti and what it means to those who produce it. To a realtor graffiti means lower home prices and a sign of urban decay. To the police it means illegal activity in the form of property damage and vandalism. To sociologists and anthropologists it has meant many things, from membership in a deviant subculture inspired by a subordinate class standing to participation in graffiti as a career with maximum fame as the ultimate goal. But what does graffiti mean to a graffiti artist. To some it is their reason for waking up and for others it is a diversion from everyday life. As with many “deviant” actors, graffiti artists have not been fully represented in the existing scholarship. My research shows that graffiti artists are, before anything, people like everyone else and are driven to do what they do for reasons similar to those that inspire people in “respectable” careers. Also, careers in graffiti involve many different stages just as careers in accepted fields. This study will examine issues revolving around the graffiti artist as a participant in a deviant career and how that mirrors aspects of both “respectable” careers and the human career in general, as well as what purpose graffiti plays in these artists’ lives and why. Graffiti through the Eyes of the Artist Scholars from various disciplines have shown interest in graffiti since its inception during the late sixties in New York. The majority of the studies revolving around graffiti have been carried out from an etic perspective, ranging from graffiti’s 4 effect on a community to the actual grammatical devices employed by graffiti artists. Most scholarship about graffiti is out of date. Much of the literature talking about spray paint graffiti focuses on the typical, somewhat “idealized” form of graffiti writing that was prevalent in the 80s with the emergence of hip-hop culture and time-capsuled in films such as Wild Style and Style Wars. Most of the remaining literature on graffiti revolves around gang graffiti, especially in Los Angeles and other metropolises, such as in Susan Phillips book Wallbangin’ (1999). This body of work has left out a vast population of graffiti writers throughout the world. In the United States, graffiti is gaining popularity with an increasingly diverse group of young people with motivations and styles to match, who are not necessarily connected to hip-hop or gang worlds. The voice of those creating graffiti has gone largely unheard. Recently, however, a scholarly effort has been made to recognize the agency of graffiti artists and make their voices heard, although none of this has revolved around smaller urban centers or less traditional graffitists. This attention has, however, raised new issues surrounding the graffiti artist as a person. I will advance recent scholarship through an emic look at the issues of identity, motivation, and community in the lives of Asheville graffiti artists. Here I will outline the specific ways recent authors have analyzed graffiti artists, with particular focus on the deviant career model as it applies to graffiti artists. Classification Graffiti has been divided into three categories (Bowen 1999; Docuyanan 2000; McDonald 2001; Rafferty 1991). This division of categories is not universally accepted. Each category has a specific type of artist with which it is associated. Docuyanan (2000) types graffiti artists as writers, taggers, and gang members. Taggers are defined by their 5 emphasis on quantity of graffiti. Writers spend more time developing their style and skills, as well as put more time and commitment into creating elaborate productions often called “pieces”. Above: wall with tags in a downtown Asheville alleyway Gang members’ primary focus is promotion of their gang or location. This classification is not supported by much of the recent scholarship on graffiti (Bowen 1999; Rafferty 1991). The classification of writers as exclusively those who devote more time developing style is not consistent with other literature as well (McDonald 2001). The category of writer can include both those graffiti artists who create elaborate pieces and a simple, commonplace tagger. The term comes from the fact that the graffiti artist is writing the word or word symbol associated with them (McDonald 2001). In contrast, Rafferty’s distinction matches the more generally accepted categorization of graffiti art (1991). The three types of graffiti recognized by Rafferty (1991) are political/slogan graffiti, tag graffiti, and murals or pieces. Slogan graffiti, as characterized by Rafferty, is not present in Docuyanan’s classification scheme. This 6 graffiti is characterized by its similarity to advertisements, which attracts attention, and often carries with it a cynical nature. An example of such a provocative declaration identified by Rafferty goes as follows: “Despise authority: It despises you!” Tag graffiti is the most basic and original form of modern graffiti. Bowen describes tags as a word symbol used to show presence of a writer in a given area (1999). He suggests that it consists of stylized letters formed together, resembling a logo, and representing the writer’s name. Murals or pieces, which are more elaborate representations of a writer’s name, often with unrelated decorations and characters, include multiple colors, layering, and three dimensional effects, are the natural evolution from a tag. These graffiti are closely tied to the art world, whereas tags are associated with crime and vandalism. Bowen links this transition to an interest in quality of work rather than the association with the illegality of the activity. Above: a piece by “MOMS,” Asheville’s most prolific graffiti crew 7 I attempted to locate a varied group of graffiti artists, while primarily focusing on those artists that create pieces. My reasoning for choosing to focus on muralists arose out of the increased social interaction inherent in the inclusion of more learned skills involved in the production of a piece, as well as the implications this has for the creation of a more well defined subculture within the more generalized subculture of all the individuals that create graffiti in some form. Career Graffiti artists generally follow a set career path as laid out in Lachman (1988), Macdonald (2001), and McDonald (1999). Becker established the concept of a deviant career with his discussion of the stages of smoking marijuana as a career (1963). Best and Luckenbill (1981) define some differences between a deviant career--that of a graffiti artist--and a “respectable” career. It is less likely that deviant careers will fall into a straightforward hierarchy and they are less likely to continue in an in an upward manner. Best and Luckenbill describe a deviant career as a “walk through the woods—while some people take the pathways marked by their predecessors, others strike out on their own; some walk slowly, exploring before moving further, while others run, caught up in the action” (Best and Luckenbill 1981:244). Benefits are not likely to increase as a deviant career advances. Also, it is more likely that deviant careers will be split into multiple short-term engagements rather than a continuous involvement. Macdonald finds fault applying this concept to the career of a graffiti writer. Macdonald contests that, as with a traditional career in a large company, graffiti writers work hard to move up within a hierarchy defined by standardized stages of activity. 8 Writers in the graffiti culture do not gain any financial reward from their work. Instead they are paid in symbolic capital in the form of fame or recognition. Most of Macdonald’s informants called upon this symbolic capital as their main reason for writing. Becker parallels the deviant career stage of learning the proper technique to smoke marijuana with an artist’s need to learn “the technical abilities, social skills and conceptual apparatus necessary to make it easy to make art” (1982:229). Lachman takes the next step and asserts that this need to learn the proper technique to take part in a deviant subculture mandates that “an already skilled mentor be present, and therefore social and geographic concentrations of graffiti writers should be reproduced over time” (p230, 1988). Graffiti careers can also be paralleled by the more general human career, as laid out in Walter Goldschmidt’s (1990) work in The Human Career: The Self in the Symbolic World. Here Goldschmidt defines career as the activities of motivated people or, more specifically, the “trajectory through life which each person undergoes, the activities he or she engages in to satisfy physical needs and wants and the even more important social needs and wants” (1990:106). Here the human career is defined as serving both the physical being and the symbolic self. A deviant career in graffiti does not include the physical part of this definition, but it can be applied to some deviant careers, such as addicted drug users. Goldschmidt writes of the human career, “the ultimate reward is prestige, or more basically in psychological terms, the satisfactory sense of self” (1990:109). Most scholars have been hung up of the first half of this statement and assured that prestige alone is responsible for a graffiti artist’s ability to 9 attain a “satisfactory sense of self,” whereas I will point to different ways in which graffiti artists conquer satisfaction. The graffiti subculture has been diagnosed in a way similar to a traditional, smallscale, egalitarian community, such as the Mekranoti of Central Brazil in research conducted by Dennis Werner (1984). This diagnosis essentially suggests the following: everyone starts on an even scale; there are no personal possessions to differentiate status; differentiation comes from talent and behavior, i.e. style, judgment (respect for superiors/not painting over), placement of pieces, etc. in the graffiti world are equitable to war skill, hunting, craft skills, etc. in the Mekronati. In the human career “social organization is not uniform and a good deal of variance can be attributed to the particularities of ecological condition” (Goldschmidt, p.112, 1990). The small size of Asheville as an urban center contributes to the lack of intense rivalries and animosities between graffiti crews that are present in larger cities. In the same way hunter/gatherer societies in similar ecological circumstances often reflect each other, the graffiti culture in Asheville should reflect those present in other small urban centers with strong art scenes. Unfortunately, I was unable to track down any sources that looked at cities even slightly resembling Asheville. Methods Graffiti artists are not the easiest people to track down, especially with the recent crackdown and graffiti taskforce put into place by the Asheville Police Department less than a year ago. Although all the graffiti artists with whom I spoke associate with a specific name or names, anonymity is essential if a writer is to remain on the scene of the underground graffiti world for any length of time. 10 Methods for studying graffiti artists in the field traditionally have a rather narrow range. Participant observation and interviews make up the majority of data collection techniques employed by researchers trying to get a closer look at the people behind graffiti. McDonald is the only researcher that reports having used “group discussion,”-this seems to be used in lieu of participant observation and resembles it rather closely as well (1999). The sampling techniques in most of the literature resemble those which I employed in my research. Snowball sampling is the preferred and most effective method to find informants involved in graffiti (Lachman 1988; Macdonald 2001). Making phone calls was Macdonald’s initial means by which she obtained informants. Lachman followed the same path that I did by seeking out various members of the community, such as gallery proprietors, that could get him in touch with informants. From this point he asked for references and formed his body of participants. In the literature I have reviewed, researchers have accumulated 10 to 37 informants using techniques similar to mine. These studies, however, were all carried out in cities larger than Asheville, such as Melbourne and London (McDonald, 1999; Macdonald, 2001). It wasn’t as easy to obtain as large a group of informants in the modest sized city of Asheville. My study is based on qualitative data gathered from participants’ descriptions of experiences as graffiti artists in Asheville. Research data was collected through interviews (both formal and informal) and a very limited (time spent with the graffitists before and after interviews) amount of participant observation. The participants were not selected randomly; because of the subversive nature of graffiti writing, the identities of graffiti artists, often called “writers,” must remain private and therefore no sampling frame of the target population exists from which a random sample could be drawn. Also, 11 the target population is so small that non-random sampling was a more effective way to find participants that can provide relevant information. Snowball sampling proved to be a helpful technique for locating additional interviewees. Before my snowball sample could be attained I first had to gain access to at least one graffiti artist. My research proposal poster presentation actually proved to be a great help to me. A student saw my poster and helped me to get in contact with a friend of hers. This friend turned out to be very willing to share information and also introduced me to another writer. In total, this initial connection at the poster presentation led me to about two hours worth of interviews with two different informants. I queried friends in the Asheville art circle as to whether they knew any graffiti writers or anyone who may be able to help me in my search. One particular gallery owner, whom I have known for the past couple of years, was able to get me in touch with several other graffiti artists, only two of whom allowed me to interview them. I gained access to the final two informants through a friend at Wilson by chance. I was just talking to him and some friends about my project and it just happened that he knew somebody who had been involved in the Asheville graffiti scene for several years. I got his number and he turned out to be very open to discussing his involvement with graffiti, but not as open as others in sharing referrals even though it was obvious in our interviews that he knew several other writers. From him, I was able to milk one other informant. To ensure that I received all possible referrals from these sources, I always explained my study and that/how confidentiality of participants would be protected. Except in one case, I was surprised with the freeness people would give me others’ phone numbers and names; the problem turned out not to be getting in touch with possible informants, but rather getting 12 this people to agree to meet for an interview. The general reluctance from contacts to participate in my research was the single greatest barrier in obtaining my sample population. However, those that did eventually sit down and talk with me always appeared comfortable and to speak freely. I conducted ten interviews with six informants over the course of about a month. My informants included two college students, two college graduates, and two high school graduates (without any further education). They ranged in age from 19 to 28 and all but one lived in Asheville proper, the exception being a student who lives with her parents in Hendersonville, but attends AB Tech and claims to spend most of her time in Asheville. Early stages The scholarship on graffiti has particularly noted the presence of two aspects in the early stages of a deviant career in graffiti. These two traditionally referenced features are the presence of a mentor and the desire for fame, although the latter of the two has, at times, been considered supplementary or only after the occurrence of the first. Both of these career characteristics have implications pertaining to the creation and maintenance of a subculture. In regards to smoking marijuana, Howard Becker found that a user “must learn to use the proper technique so that his use of the drug will produce effects in terms of which his conception of it can change” (1963:47). He extends this idea to professional artists in his book Art Worlds (1982) and Lachman asserts that Becker would thus predict that those just entering the graffiti subculture “would need to learn the techniques for, and desirability of, writing graffiti from an already skilled mentor, and therefore social and geographic concentrations of graffiti writers should be reproduced 13 over time” (1988:230). This notion was articulated to some extent by every graffiti artist with whom I spoke. The degree to which a mentor played a role in my informants’ introduction to the subculture varied, both in stages of involvement (when the mentor was present) and amount of influence over his pupil(s). In the case of Kendall, two generations of mentors and students are identifiable. He explained to me on a dreary, Appalachian winter’s day in the back of a downtown coffee shop how a friend of his started tagging and, in a minor way, became his mentor. This friend of his, he explained “got into it because this guy came up from Chile. His name was Lupe and he did a lot of street art down in Chile and they met and he kind of picked it up from him.” In Kendall’s case he received very little actual help from his “mentor.” I put mentor in quotations because in this case the person responsible for creating Kendall’s interest was little more than an impetus which set in motion his more individual learning. Kendall tags, which came as a surprise considering his throw-back eighties track jacket reminiscent of Run DMC; he does not do murals or pieces. This could be due, in part, to him never having experience with a more traditional teacher-type mentor. His “mentor” was not “already skilled” by any means. Kendall said “he just started tagging this one tag and I was like that’s cool man. Like, why are you doing that? Well, I just wanted to get some notoriety and it’s a lot of fun and it’s a really cool thing to get into. And, so I started getting my tag and all that and you get better and better and it’s really interesting as time goes on.” Kendall was introduced to graffiti through tagging and thus has himself become a tagger; he hasn’t experienced any great change in ideology or environment to cue an evolution from his strictly tagging status. His mentor learned from 14 Lupe that an audience exists for graffiti and in turn he passed this, along with enough knowledge to learn the technique of tagging, to Kendall. Although this idea of needing to learn that graffiti has an audience is popular in the literature and to a limited extent with my informants, the understanding that there is an audience for graffiti seems to emerge experientially more than by means of a mentor. Through various interactions and involvement in graffiti culture, writers quickly realize that an audience exists from their work. Although a mentor was minimally present in Kendall’s initiation to graffiti, a more powerful and important force really caused his conversion to the world of graffiti. This force has been present in all of my informants’ stories in one way or another. This force I speak of is potential fun, fun with friends. Graffiti was simply another outlet for having a good time with pals and often arises out of participation in other joint activities. When discussing his origin of interest in graffiti, Tony said, “Mostly [my friends and I] would just meet up after school and just skated together. We’d just get into, just through skating, just got into it. Somehow somebody was drawing characters and names and stuff…We would always hang out in the tunnels and stuff.” Here skateboarding and hanging out together in tunnels led to his involvement with graffiti, although there is the slightest notion of a mentor present in the line about how “somebody was drawing characters and names and stuff.” Again here, the “mentor” is not a clear-cut teacher, but more of an inspiration. He is a peer without any sort of special knowledge or skill, which he is passing onto his pupil. He just happened to be the one who decided that doing graffiti would be a fun activity for him to participate in and his friends, Tony included, quickly recognized the same for themselves. Skateboarding and skate culture was an 15 existing outlet for fun. Just as Becker suggests that a community is necessary for the proliferation of deviant careers, the emergence of participation in graffiti was a natural evolution for Tony and his friends that emerged out of the community and its shared values. The fun for him was both in the experience of doing the graffiti, but also in the sharing of the graffiti with his friends. Friends recurred as a key element to my informants’ initial interest in graffiti and its enjoyment once begun. “We always drew in our notebooks at school, something to pass class time…and just meeting up after, showing each other what we did,” Charles expressed here the way in which graffiti attributed to these friendly social bonds. Although actual publicly visible pieces are not the subject at hand here, this quote iterates ideas expressed consistently about the influence of friends on the appeal of graffiti and part of what makes it pleasurable. Gabe also told tales of the fun he and his friends would have and the way in which graffiti was initially more a product of that than anything else. Growing up in a rural environment, he and his friends found many outlets to get their excitement: “I was always interested in fucking shit up, but probably more like breaking windows and toilet papering cars, and like, pulling weird tricks, like lighting the road on fire kinda stuff. We would tag a little, but it was more just a part of all this other shit.” Not until he got to Asheville did he really start his full-fledged career as a graffiti writer, “…definitely living in a more urban environment, more cement, more concrete, shit ass buildings everywhere on top of each other definitely creates the bug.” Goldschmidt discusses the way ecological circumstances affect the human career; ecology does not “cause careers”, but it establishes boundaries which affect “forms of behavior, traits of character and patterns 16 of collaboration” (1990:113). The transition from a rural to an urban lifestyle affected Gabe’s career path and encouraged him to progress in a way that would have otherwise been unavailable, or at least highly unlikely. An existing community is always present during the early stages of an Asheville writer’s career in graffiti. The mentor is a peer without any special skills and does nothing more than introduce graffiti to the community. The traditionally referenced graffiti mentor has been replaced by the presence of a like-minded group of individuals as the essential element during one’s initial involvement with graffiti. Joint participation in the deviant behavior of spray-painting on walls provides participants with a way of achieving fun, while simultaneously strengthening existing social bonds. Multiple Short-term Engagements Scholarship on deviant careers has found that actors in deviant careers do not participate continuously, but rather their involvement is broken up into multiple shortterm engagements or, in the case of graffiti writers, bursts of activity in which a writer will go out and paint for several days in a row immediately followed by a month or two without picking up a spray-can. My informants did not express an addiction to graffiti; they did not need to get their fix by making graffiti on a daily basis, but this does not detract from their role as part of the graffiti subculture. They are still graffiti artists when they wake up and brush their teeth and get dressed. Carli told me, “I could go for a month without doing it then…then I’ll just do it for like four or five days straight…so, it just goes on.” Despite the way Asheville graffiti artists deny a need to go out and paint graffiti, all of the writers I spoke with are still participating in and contributing content to the 17 graffiti culture. Some speak as though it’s just a side note, thereby stressing the importance and priority of their other forms of “acceptable/traditional” art, although this came off more as a way of reaffirming themselves and their path in life. All but one of the piecists with whom I spoke expressed that they only do graffiti intermittently, but the fact is that all of them have continued to go back to doing graffiti work throughout the years. Not one of my informants has outright dropped the creation of graffiti from their lives. This hints at graffiti being more important in many artists’ lives then they acknowledge. Gabe denied the importance of graffiti in his life: “…it’s not a necessity for me; it’s just another interesting thing to consider. I’m process over product in most everything I’m doing right now, the reason I’m doing it is for the sake of doing it. That’s what drives me; that’s the shit I need…” Though, in this quote, Gabe is referring to the way he prioritizes “process over product” in all his creations and aspects of life, the proposal that the action of creating graffiti is equally or more important to the writer than the tangible, visible painting they’ve fashioned from an aerosol can recurs throughout the thoughts of Asheville graffiti artists. Even when graffiti writers take a break from painting they still are participating as audience members for other writers. Once you’re in it you’re in it, when it comes to the culture of graffiti. Just the way a skateboarder will always take note of skate spots or a birder will take note of the birds they see even on a casual walk (one not motivated by the quest for spotting birds). Gabe gives an example of how he plays a role in the subculture even when he’s not painting: “I walk everywhere I go right now. I got a studio in town where I work at and I got here and my house is like a mile that way…so I walk to the studio downtown this morning then walked back home then I walked here. So it’s like, I 18 cover ground. I see what everyone’s doing.” This, in turn, affects the graffiti he will do next – where, what, and how he will create his next piece. “If anything, I strive to do something different just because it seems so homogenized. Like, people are doing the same kinds of things, like there’s variation in it, but it all is basically working with the same ideas.” Observing, creating, discussing, interpreting responses to, and learning about graffiti all interact with each other to form the overall experience a writer has as part of the graffiti subculture. It’s the creation aspect, the actual experience on the streets (usually with friends), however, that is most valued by writers as they recount their experiences and time involved with graffiti. From writers’ initial involvement emerging out of social fun with friends to a time-consuming production piece involving the efforts of ten people, Asheville writers consistently return to the experiential aspect of graffiti as most prized. This may not come as a surprise in the instances of early participation where the end product may be a unattractive (by traditional standards) scribbling of someone’s name on a tunnel wall, but even in the case of a major production where a large group of people collaborate to execute an elaborate, technically perfect mural with creating an artistic masterpiece in mind, this concept of process over product is predominant. All the things that come along with a completed product (respect of other writers, general notoriety, sense of accomplishment) take a back seat to the experience as it’s happens, which ultimately is measurable in and equates to…fun! It is true that all the other aspects that go along with creating graffiti are appreciated by its makers – even if fame isn’t the ultimate goal, my informants still appreciate positive feedback about their work – but these traditional cited motivations can not be credited for the thriving 19 subcultures of graffiti writers that exist throughout the state, country, and world and have been present in some form for thousands of years. Progression Graffitists express the existence of a natural progression in doing graffiti, although not everyone chooses to follow this progression. Howard Becker (1963) established the concept of a deviant career with his discussion of the stages of smoking marijuana. Best and Luckenbill (1981) further developed this concept through defining the differences between deviant and “respectable” careers. One of the differences identified by Best and Luckenbill is that deviant careers are less likely to fall into a straightforward hierarchy and they are less likely to continue in an upward manner. Only half of this statement is consistent with a graffiti artist I interviewed on a dreary day in a downtown Asheville coffee shop. I wanna keep going as long as I can and develop it; ya know, I wanna get really, really good. And, I guess I’ll just keep going until I get busted”, a UNCA tagger told me. He went on, “…if you want to really get into the art of it all than you sit and take your time and do a nice piece. And, eventually as you get better you learn how to do these pieces”, “real fast” his friend interjected. He continued, “…real fast…I’m not really good enough yet. I’m, ya know, still trying to make my way up to that level. Here Kyle expresses interest “to continue in an upward manner” which Best and Luckenbill suggest is an unlikely aspect to a deviant career. However, throughout the interview, he seemed to express more contentedness with his current status as a tagger than he expressed interest in learning to do more elaborate graffiti. When I asked him where he sees himself in the future in regards to graffiti, he said he wanted to get really good, but ultimately only continue until he got busted, not until he became a competent artist when it comes to designing and executing a piece or mural. Of all the writers I 20 spoke with Kyle is the only one who has not yet graduated from the level of tagger. This suggests that an upward progression is present in graffiti careers, but it is not a mandatory feature. It is a matter of whether or not a tagger can understand the incentives to putting in the time and whether or not he/she is motivated to gain the different incentives that go along with being a piece artist. Kyle seems to understand the incentives – “If you’re talking about getting a good rush the best thing is to like find the perfect spot and set up there and like…ya know get it all finished” – but doesn’t appear to have had enough motivation, or simply is happy with where he is, thus far in his career to make this next step. This is equally true in respectable careers. Some people just work for their entire life at the same boring office job with an interest in moving up, but without being genuinely motivated it doesn’t happen. Understanding the incentives of progression and motivation are, however, not the only necessary factors in making actual steps forward in a career, either deviant or respectable. A graffiti artist must possess a certain level of natural talent if he/she wants to make the step from tagger to “piecists” (term used occasionally for piece artists/muralists). Carli makes a distinction between taggers and muralists, “…not to be mean, but bombing is mostly guys and they’re usually like, how they act in real life fits it. Bombers are usually smart asses and sometimes they’re assholes and like more piecists are real quiet, who do art, like other forms of art, like painters and stuff. So you can just tell what kinda style anyone would do.” If graffiti artists who primarily create pieces are usually artists that work with acceptable mediums as well – all of the piecists I interviewed, which would be all but one of my informants, did do other forms of art – 21 then it would make sense that a natural artistic ability be present in all of these writers, whereas writing a tag is not particularly demanding in the technical artistic sense. Progression is also controlled by time. As in any area of interest, the more you put in, the better you get, and the more you get out of it. There are so many factors that go into creating elaborate pieces of graffiti that most artists acknowledge that there is still a lot of room for them to grow and get better and that they are striving to improve almost all the time. Just as Jeff Ferrell observed while accompanying a group to the creation of a production piece, “they pay attention to and discuss the amount of paint remaining, which they determine by the weight and feel of the can”, it came out in several interviews that the artists know a lot, but that there is still much to be learned (1993:23). “From observing them (more skilled friends/graffiti artists)…ways of layering and blocking in and making shit happen faster and smoother and about how to use different caps and what paints come out at the right consistency and speeds and there’s all these variables which I have begun to learn,” this excerpt from Charles touches on the immense amount of knowledge and skill that is necessary for a piecist to reach the highest possible level of technical ability in the creation of murals. About half of my informants are not originally from Asheville. All of these artists experienced a similar conversion into the Asheville graffiti scene from their graffiti roots in their respective home towns. Once arriving in Asheville and becoming involved in the graffiti scene and the art scene in general, these non-natives expressed that graffiti was something that grabbed a hold of them and participation increased exponentially once they found a niche in the Asheville graffiti scene. Tony, originally from Winston-Salem, told me about a big step forward in his graffiti, 22 …I just met some people and then after that, really quickly after that, I met a lot of people that they knew; and, it just, like, accumulated. And then it became more of an organized thing, like, people doing it and then everybody showing pictures. Keeping up with what’s going on…look at everything all over the country, all over the world. And then you just get more involved and like, realize that everyone’s looking at everyone’s stuff. Although Tony had been dabbling with graffiti since his arrival in Asheville, it wasn’t until he got in with other artists that his career really took off and he started to progress. Even for the most artistically devoted graffiti artist, Tony being that to my group of informants, the art of graffiti alone is not enough to prompt progression. This means that involvement in graffiti as a social, and often group, endeavor provides an extra push. The addition of other people and friends in one’s graffiti experience greatly changes the overall process of participation in graffiti subculture. The combination of piece graffiti and social groups, which naturally gravitate towards each other, introduces many new processes and changes existing processes revolving around graffiti. Tony was now able to share his art and ideas with, as well as receive input from, other people. This aspect of career progression shows through in the art; new styles and themes emerge as new techniques and ideas become accessible. He now often creates pieces as a collaborative effort. This involves both more planning and a different experience during the painting process. The group needs to organize itself before hand by making sure they have the right paint and enough of it. Also, in some cases the group will meet up before hand (as opposed to on site) to plan out the mural. These aspects of interaction away from the actual graffiti site add to the overall appeal and rewards gained from creating graffiti. This contributes to the forming of social bonds, as does the collective action during the creation of the piece. “Drunk, 23 drunk, being drunk is the fun”, Carli told me about the experience of making a piece. Although this has implications about deviant action (Carli is only 19, below the legal drinking age) in addition to graffiti, it also implies the way in which the end product of the actions takes a back seat to the actions themselves. The rush from “the intersection of creativity and illegality as the paint hits the wall” is present when painting alone, but being able to share that rush with others is what really gets people enraptured and excited about graffiti as their careers progress (Ferrell, p.28, 1993). One of Jeff Ferrell’s informants from the “Syndicate” crew in Denver, Colorado discussed what held together their crew: What hold the Syndicate together is art, graffiti. Motivation too, because you got to be motivated to do a piece. What holds the Syndicate together also is, because me and Eye Six are just like best friends…And everybody is just like real cool…We’re just all really tight and cool. It seems like we’re kind of close, you know. It’s not like we’re gangsters. We’re a gang that needs a sense of belonging and a sense of togetherness or whatever. Just get together. It’s like a band. You get together and do you’re thing. Here Rasta 68 starts by saying the art is what holds the group together, but quickly digresses from that statement. My informants openly acknowledged that the art was not the most appealing aspect to graffiti. Again and again, my informants emphasized the group, not the individual, in our discussions about career progression. The community is crucial in each step forward. It is not the additional individualistic rewards that graffiti artists seek through progression, but rather the new and different social bonds and interactions that go along with it. Community Affect If you were to inquire to the average American how graffiti affects the community you wouldn’t be surprised at receiving overwhelmingly negative responses. I did inquire 24 to several graffiti writers how they feel what they do affects the community and the responses were overwhelmingly mixed (not from person to person, but each informant offered a consortium of varied impressions) and well considered. I think it’s a really volatile subject that really…a lot of people get really worked up about around here. I know around here in these buildings (in reference to his and the surrounding buildings of the river district) they do. Cause there’s just this whole gentrification process of these properties becoming worth so much and so much more money and all these people building houses and moving down, the businesses coming…that they don’t want all the gritty kids, want to live in the warehouse-type style, want to do art, paint and that sort of fucking post-industrial environment are all here doing this shit that now the things happening toward the money they don’t want that shit here. They (the “gritty kids”) don’t want the change in the rules so the train doesn’t blow it’s horn because rich people don’t like to live where the train blows it’s horn. So…they’re gonna dig big gates so the train doesn’t have to blow its horn anymore or some weird shit. Gabe Graffiti artists in Asheville have a conscience. That’s not to say that they don’t get a kick out of the illegality of making graffiti, but rather that they understand the implications of their actions. Naturally accompanying a graffiti artist’s conscience is his/her agenda. Though everyone I spoke with expressed anti-establishment sentiments in some way, their agenda seemed to play little influence in their graffiti on a whole. Graffiti artists understand perspectives outside of their own and at times venture so far as to allow those perspectives to manipulate their overall ideology as well as specific choices from piece to piece, in a way that is rarely expressed from the other side. Public officials, police officers, and especially property owners, have historically and, continue to show no interest in trying to understand the perspective of the graffiti artist. This lack of understanding is an essential element to keeping graffiti culture going. Considering that the experiential aspects are continual referenced as the most appealing, if the crucial element of graffiti’s subversiveness was removed, the culture would die with it. 25 You can affect the community by deciding on which thing you want to paint, in certain ways. Like, you’ll piss someone off…you don’t really see it on the side of a house…Part of the community likes it and part of it completely hates it. So, you’re affecting it the whole time you’re doing it. And then by choosing to paint a dilapidated building instead of…would have a higher positive than if you would paint a building that’s not in shambles. Charles Both Charles and Gabe work, live, and spray graffiti in the river district. They are also both unhappy about the current and prospective developments in their neighborhood. By painting in the river district they understand whom it affects and how it affects them. The presence of graffiti in the area negatively affects the new, highly priced development, while maintaining the existing dilapidated, post-industrial environment that drew the current river district population to its banks with low rents for studios. This wasn’t expressed as a main reason for doing graffiti but did seem to factor in somewhat in their choice of location for a piece. Motivation and Identity Motivation in Asheville graffiti artists is a diverse issue. Not only is there variation between artists, but also, there is a great deal of changing motivations for specific artists as their careers transform and evolve over time. Early in many of my informants’ careers graffiti acted as little more than an outlet for having fun, while participating in a counter-hegemonic activity. Also, graffiti was merely an aspect of a greater set of actions and circumstances, usually involving a gathering of friends. The fun that graffiti artists achieve through their participation in graffiti culture is a specific kind of fun. This culturally specific fun and the community from which it arise are mutually exclusive – the fun would not be achieved without the presence of the group 26 and the group would not exist if the collective action didn’t produce a feeling similarly perceived and appreciated by its members as fun. Before their involvement in the graffiti world my informants expressed that they already were participating in other behaviors deemed deviant by society, including, in some cases, various forms of vandalism. In this way my informants seemed to have a pre-disposition towards becoming involved with graffiti subculture. This also suggests that the fun, which Asheville graffitists seek above all other potential rewards, arises from an existing perception of deviant behavior as fun and is maximized by sharing the experience with like-minded individuals. Asheville graffiti artists, through their involvement in graffiti subculture, are not seeking great individualist fame or respect from unknown writers. Instead they are interested in attaining a place within a community oriented around the creation of graffiti – the combination of the two equating to a culturally specific notion of fun. Asheville graffitists are striving not to become a larger than life entity but are seeking to confirm their identity through involvement in friendly social interaction, rather than through competitive assertion of power within the subculture. 27 References Cited Becker, Howard 1963 Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: The Free Press. 1982 Art Worlds. Berkley: University of California Press. Best, Joel, and David Luckenbill 1982 Organizing Deviance. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall Inc. Bowen, Tracey 1999 Graffiti Art: A Contemporary Study of Toronto Artists. Studies in Art Education 1: 22-39. Docuyanan, Faye 2000 Governing Graffiti in Contested Urban Spaces. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 1: 103-121. Ferrell, Jeff 1993 Crimes of Style: Urban Graffiti and the Politics of Criminality. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc. Goldschmidt, Walter Rochs 1990 The Human Career: the Self in the Symbolic World. Oxford and Cambridge, MA: Basil and Blackwell. Lachman, Richard 1988 Graffiti as Career and Ideology. The American Journal of Sociology 2: 229250. Macdonald, Nancy 2001 The Graffiti Subculture: Youth, Masculinity and Identity in London and New York. Hampshire: Palgrave. McDonald, Kevin 1999 Struggles for Subjectivity: Identity, Action, and Youth Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Phillips, Susan A. 1999 Wallbangin’: Graffiti and Gangs in L.A. Chicago: University of Chicago Press Rafferty, Pat 1991 Discourse on Difference: Street Art/Graffiti Youth. Visual Anthropology Review 2: 77-84. Werner, Dennis 1984 An Anthropologist’s Year Among Brazil’s Mekranoti Indians. New York: Simon and Schuster. 28