B. Considerations of the Court

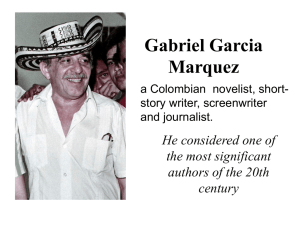

advertisement