Teachers` guide - American Voices

advertisement

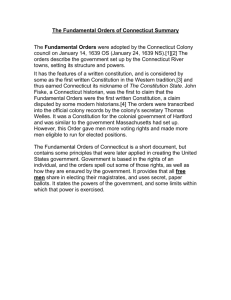

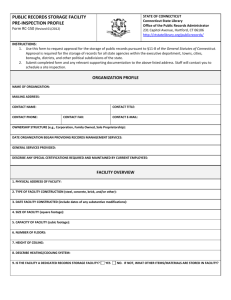

Historical Scene Investigation (HSI) American Voices Summer Institute Curriculum Project Kelly Cooper, Marlborough Public Schools Chris Weaver, West Hartford Public Schools Intended grade level: 4 Topic/Curriculum Link: Connecticut has long been known as the Constitution State. Some can argue this is because of the role of Connecticut in shaping and writing the Constitution of the United States of America through the work of Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth in formulating the Connecticut Compromise. Others can argue the state nickname refers to the Fundamental Orders of 1639 as the first example of a written constitution. Connecticut also has a rich history or “constitutional” documents starting with the Fundamental Orders, leading to the Charter of 1662, then the Connecticut Constitution in 1818, and finally the revised constitution currently being followed in 1965. All of these events and documents have impacted government, as we know it today. Essential Understanding/Learning Objective: Why is Connecticut’s nickname the Constitution State? What role did Connecticut have in shaping our government and how did it evolve over time? Students will be able to explain what a constitution is and make decisions about which documents are really constitutions. Students will be able to explain what the Fundamental Orders of 1639 were, why they were important, and how they compare to our current government. Students will be able to explain what the Connecticut Compromise was, who was responsible for it, why it was important, and how is has impacted our current government. Students will be able to compare and contrast sections of the various constitutions throughout Connecticut’s history. Student Books Connection: A True Book: The Constitution of the United States by Christine Taylor-Butler (Scholastic) Procedure/Student Activities: What’s the Context? (Background and Introductory Activities) Activity 1: Image analysis Materials and primary sources: magnifying glasses (at least 6), Document A: Bradley Steven’s Connecticut Compromise Mural (at least 3copies), Document B: Albert Herter’s 1913 Painting, “The Signing of the Fundamental Orders of the Constitution 1638-39” (at least 3 copies), student research notebooks Procedure: Set up investigation stations with one artwork copy and one magnifying glass around the room and break students into groups of 2 or 3. Have each group examine the artwork using the magnifying glass to focus on certain details of the larger image. Have students respond in their research journals to the following questions: 1. What do you see? 2. What do you think is happening? 3. Who do you think these people are? 4. What message does this send? 5. How does it make you feel? After about 5-10 minutes, have the groups switch and repeat their examination with the other piece of artwork. Finally, come together as a whole group to discuss what they noticed and what they think is happening. Activity 2: Possible Sentences Materials and primary sources: vocabulary list, student friendly definitions Procedure: Write or display the 10 constitutional vocabulary words. Pronounce each word for the students. Ask students to create a sentence using at least two of these words and share. As students are sharing, discuss meanings of the words with students. Once all 10 words have been discussed, ask students to again create a sentence using at least two of these words to show meaning and understanding. Display these sentences in the classroom throughout the duration of the unit and go back and add/change them as they come up. Activity 3: What is a constitution? Materials and primary sources: A True Book: The Constitution of the United States (chapter 1), chart paper and markers, index cards, crayons Procedure: Partner students and have them discuss what they think government is, and challenge them to list at least five purposes for government. As a class, discuss these purposes together and list them on chart paper. You can display this list as a reference. Read the first chapter of the nonfiction children’s book aloud. Discuss with the students who needs a constitution and why people need a constitution. Have each partnership create a colorful illustration or symbol to represent the ideas of a constitution. Together as a class, create a working definition of a constitution to display prominently throughout the unit and hang the symbols around the definition. Becoming a Detective (questions and topics to investigate) Activity 4: What were the Fundamental orders of Connecticut? Materials and primary sources: Document C: Fundamental Orders of Connecticut (with transcript), Document D: Thomas Hooker sermon notes from Henry Wolcott, Document E: Structure of the General Court 1640, Fact Pyramid and Because Box organizer, Student research notebooks Procedure: Display reproduction of the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut and explain to students what this document is, making sure to incorporate the following information: The Fundamental Orders were written in 1639 They united the town/colonies of Hartford, Windsor and Wethersfield (make sure you don’t tell the students that the orders established a governmental structure) Then, review and discuss the transcribed notes from Thomas Hooker’s sermon on May 31, 1638 as recorded by Henry Wolcott (displayed on an overhead or on a Smart Board). Show students the image of Henry Wolcott’s Journal that can be found at the Connecticut Historical Society. Distribute the transcript of the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut along with the Structure of the General Court, 1640 Graphic depiction. Ask the students to review the document in small groups, using the following critical questions and have them write their responses in their research notebooks. What does this document say about Connecticut the 1600s? What rights did the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut give to Connecticut Colonists in 1600? Why was this document important? Do you think the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut is a constitution? After the students review the documents, have them complete the Fact Pyramid and Because box organizer in their small groups and then share the results of their investigation. Activity 5: What was the Connecticut Compromise? Materials and primary sources: Document F: Madison Debate Notes, Reader’s theater of the Madison debate notes, We The People (Lesson 9), Student research notebooks, Document G: Information on Connecticut’s founding fathers, Copies of pages 76 and 77 from We The People, Making Sense of History pp. 178-185 Procedure: Discuss with the students what a compromise is and why it is important to compromise. Using the picture book, A True Book: The Constitution of the United States of America, read chapters two and three with students, stopping to discuss along the way. Distribute copies of We The People and begin to read lesson 9 with the students. Complete the activity, “How many representatives in Congress should each state have?” found on pages 73, 74 ad 75. Continue reading the section on the Great Compromise found on pages 76 and 77 with the students. In small groups have the students review the documents describing Connecticut’s Founding Fathers, and instruct them to record some of their findings in their research notebook. Read the reader’s theater of the Madison Debates from Monday, June 11, 1787. Discuss the Connecticut Compromise based on the new information learned from the reader’s theater. Distribute the transcript of the Madison Debate Notes from Monday, June 11, 1787 and in small groups have the students review the debate note transcripts using the following guiding questions and record their responses in their research notebook: What were the delegates discussing on Monday June, 11? What compromise was proposed by Roger Sherman? What did this compromise do to help the large states? What did this compromise do to help the smaller states? Why do you think this compromise was so important? Distribute copies of pages 76 and 77 from We The People, ask the students in their small groups to add information into this text based on the new information they learned about the Connecticut Compromise. See example of this activity found in Making Sense of History pp. 178-185. Investigating the Evidence (list of primary sources) Document A: The Connecticut Compromise Mural http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/art/artifact/Painting_35_00003.htm The Document B: Signing of the Fundamental Orders painting http://cslib.cdmhost.com/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/p4005coll8&CISOP TR=94&REC=9 Document C: The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut (with transcript) http://www.constitution.org/bcp/fo_1639.htm Document D: Thomas Hooker sermon notes from Henry Wolcott Document E: Structure of the General Court 1640 http://www.ctheritage.org/aodg/1636full/1-8.gif Document F: : Information on Connecticut’s founding fathers http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution_founding_fathers_connect icut.html Document G: Madison Debate Notes http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_611.asp Document H: The Constitution of the United States of America (with transcript) http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution.html Document I: The 1818 Constitution of the State of Connecticut (with transcript) http://www.sots.ct.gov/sots/cwp/view.asp?a=3188&q=392280 Document J: The 1965 Constitution of the State of Connecticut (with transcript) http://www.cslib.org/constitutionalamends/constitution.htm Searching for clues (Questions to ask about sources) Activity 6: How do constitutions guarantee voters rights and how have voters rights changed over time? Materials and primary sources: images of original documents (Documents C, H, I, J), clause from the Fundamental Orders of 1639 on voters rights, clause from the Constitution of Connecticut of 1818 on voters rights, clause from the Constitution of Connecticut of 1965 on voters rights, clause and amendment from the Constitution of the United States of America on voters rights, Student research notebooks Procedure: Display reproduction of the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, the Constitution of Connecticut of 1818, the Constitution of Connecticut of 1965 and the Constitution of the United States of America. Introduce each of the documents to the students. In small groups have the students review the sections of each of the documents (The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, the two Connecticut Constitutions and the Federal Constitution) that guarantee voters rights and record their findings in their research notebooks. Give each group one document excerpt to focus on. Post the following guiding questions to help the students when review the documents: According to the Federal Constitution, what are voters’ rights? According to the Constitution of Connecticut of 1965, what are voters’ rights? According to the Constitution of Connecticut of 1818, what are voters’ rights? According to the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, what are voters’ rights? How have voters’ rights changed over time? Then let each group present their findings to the class, teaching them about their particular document. Have the students complete a quick write in their notebook detailing what they learned about voters’ rights and how they have changed over time. Cracking the case (Drawing Conclusions) Activity 7: Student debate Procedure: Ask the students why is Connecticut considered the Constitution state? Divide the students into four groups based on if they think CT is the Constitution State because of the Fundamental Orders or the Connecticut Compromise, (two groups for each view point). Have the students prepare an argument of their groups point of view based on the information that they learned. Students will work together in their small group to complete the persuasion map found at the following link: www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/interactives/persuasion_map and print a copy of their graphic organizer. Each group will elect two spokespersons to talk to the class (perhaps the following day) and present the group’s argument. Following the debate, the students will vote to determine Why Connecticut is the Constitution State? (Because of the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut or the Connecticut Compromise) Assessment: Student project: Students will creatively present their findings by choosing from the Constitutional Final Project Menu to indicate their understanding of this unit and convey their opinion as to why they think Connecticut is called the Constitution State. Student research notebooks, graphic organizers, and participation in group and class discussions will also be used for assessment. Differentiation: Throughout this topic, there are various opportunities for whole class work, small group work, partner work, as well as independent work. The Constitutional Final Project Menu allows for a great deal of student choice and differentiation. Extensions: Create a class constitution based on what students know about constitutions Examine other sections of any the constitutions Take a trip to the Old State House in Hartford to see the Thomas Hooker statue and/or the CT State Library and Museum in Hartford to see the original documents Teacher resources: The Origin of the Fundamental Orders by Edwin Stanley Welles (a paper read before the CT Historical Society on Nov. 12, 1935) Readings on Oliver Ellsworth, Roger Sherman, and William Samuel Johnson http://www.ctheritage.org/encyclopedia/ct1763_1818/toc-1763-1818.html Walter Woodward, “Creative License” Hog River Journal: http://www.hogriver.org/issues/v03n02/creative_license.htm Benjamin Hart, “Faith and Freedom” chapter seven http://www.leaderu.com/orgs/cdf/ff/chap07.html “Connecticut’s Four Constitutions” http://www.cslib.org/cts4c.htm “Connecticut Governance” http://www.ctheritage.org/encyclopedia/polgov/ctgov.htm James E. Rhodes, “Connecticut and the Federal Constitution” CT State Department of Education Curriculum Laboratory Bulletin 14, July 1945 We the People: The Citizen & The Constitution, Level 1 published by the Center for Civic Education (see http://www.cclce.org/index.php?option=com_rsform&Itemid=190 to request free copies for your class) Vocabulary List: Constitutional History magistrate Noun: a public official who exercises a judicial or executive function, such as a mayor or justice of the peace citizen Noun: a person who is a member of a country either because of being born there or being declared a member by law oath Noun: a serious promise elector Noun: one who may participate in an election; qualified voter freemen Noun: one who is free, and not a slave term Noun: a set period of time during which something happens attain Verb: to arrive at or reach reside Verb: to live in a place for a long time moral Adjective: having to do with what is right and what is wrong in how a person acts amendment Noun: an official change made to a bill, law, or other document