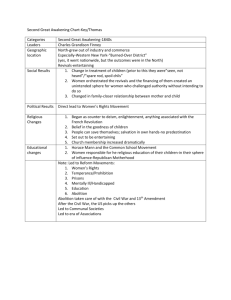

Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere

advertisement