What is Economics? 1 Chapter 12 monopoly 1 What is Economics

advertisement

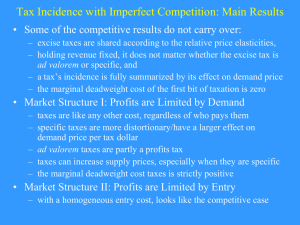

C h a p t e r 12 MONOPOLY Chapter Key Ideas The Only Game in Town A. Most buyers use e-Bay for auctions because most sellers use e-Bay for auctions. Most companies and organizations list their websites on Google because most internet browsing customers use Google to search the web. 1. These firms clearly have little competition and enjoy significant market power (ability to influence market price), so these firms can’t be operating in a perfectly competitive market. 2. Is there anything different about how firms with market power operate? Do industries with a singularly dominant firm behave differently than competitive ones? B. Students get lots of price breaks—at the movies. Seniors get price breaks at restaurants. Business travelers tend to pay higher prices for tickets on the airlines. 1. How do firms get different people to pay different prices? 2. How can it be profit maximizing to offer lower prices to some customers but higher prices to others? Outline I. Market Power A. Market power and competition are the two forces that influence the market structure of most markets. 1. Market power is the ability to influence the market, and in particular the market price, by influencing the total quantity offered for sale. 2. A monopoly is a firm that produces a good or service for which no close substitute exists and which is protected by a barrier that prevents other firms from selling that good or service. B. How a Monopoly Arises 1. A monopoly market has two key features: a) No close substitutes. The absence of any firms making close substitute goods or services allows the monopolist to avoid competition in the market. 282 CHAPTER 12 b) Barriers to entry. Legal or natural constraints that protect a firm from potential competitors are called barriers to entry. 2. There are two types of barriers to entry: a) Legal barriers to entry create a legal monopoly—a market in which competition and entry are restricted by the granting of a public franchise, a government license, a patent, or a copyright. i) A public franchise exists when an exclusive right is granted to a firm to supply a good or service. For example, the U.S. Postal Service has a public franchise to deliver first-class mail. ii) A government license exists when the government controls entry into particular occupations, professions and industries. For example, a license is required to practice law. Licensing doesn’t always create a monopoly, but it does restrict competition. iii) A patent is an exclusive right granted to the inventor of a product or service, and a copyright is an exclusive right granted to the author or composer of a literary, musical, dramatic, or artistic work. Patents and copyrights don’t always create a monopoly, but because these rights can be sold, they do restrict competition. b) Natural barriers to entry create a natural monopoly, which is an industry in which one firm can supply the entire market at a lower price than two or more firms can. Figure 12.1 shows the LRAC curve for an electrical power company that is a natural monopoly. C. Monopoly Price-Setting Strategies 1. Monopolies face a tradeoff between the price it charges and the quantity it can sell. For a monopoly firm to determine the quantity it sells, it uses its market power to choose the appropriate price. 2. There are two types of monopoly pricesetting strategies: a) Price discrimination is the practice of selling different units of a good or service for different prices. Many firms price discriminate, but not all of them are monopoly firms. b) A single-price monopoly is a firm that must sell each unit of its output for the same price to all its customers. 3. Although the practice of price discrimination appears to be for the benefit some consumers, it is really an attempt by the firm to receive the maximize price for each unit sold to maximize its economic profit. II. A Single-Price Monopoly’s Output and Price Decision A. Price and Marginal Revenue 1. The demand curve facing a monopoly firm is the entire market demand curve. MONOPOLY 283 2. This demand curve relates the market price at which the monopoly firm can sell the corresponding quantity of output. a) Total revenue, TR, is the price, P, multiplied by the quantity sold, Q. b) Marginal revenue, MR, is the change in total revenue resulting from a one-unit increase in the quantity sold. The key feature of a singleprice monopoly is that at each level of output, marginal revenue is less than the price, that is, MR < P. c) MR < P at every level of output because the single– price monopoly firm must lower its price on all units sold to sell an additional unit of output. This fact means that the extra revenue received equals the price of the additional unit sold minus the decrease in price for each of the previous units it would have sold at the higher price. As a result, the net increase to firm’s revenue, that is, its MR, is less than the price of the last unit sold. d) Figure 12.2 uses a demand curve to show how these offsetting influences on total revenues. B. Marginal Revenue and Elasticity 1. A single-price monopoly’s MR is related to the elasticity of demand for its good. a) If demand is elastic, a fall in price brings an increase in total revenue. The rise in revenue from the increase in quantity sold outweighs the fall in revenue from the lower price per unit, and so the MR is positive. b) If demand is inelastic, a fall in price brings a decrease in total revenue. The rise in revenue from the increase in quantity sold is outweighed by the fall in revenue from the lower price per unit, and so the MR is negative. c) If demand is unit elastic, a fall in price does not change the firm’s total revenues. The rise in revenue from the increase in quantity sold equals the fall in revenue from the lower price per unit, and so the MR is zero. 284 CHAPTER 12 2. Figure 12.3 shows the relationship between elasticity of demand and total revenues for all three cases. 3. A single-price monopoly will never produce at an output for which demand is inelastic. If it did so, the firm could decrease output, increase total revenue while decreasing total cost, and thereby enjoy higher economic profits. So a single price monopoly will always maximize its economic profit by producing in the elastic range of its demand. C. Price and Output Decisions 1. The monopoly faces the same types of technology and cost constraints as does a competitive firm, so its costs behave the same as the costs of a perfectly competitive firm. But the monopoly faces a different type of market constraint. a) The monopoly selects the profit-maximizing level of output in the same manner as a competitive firm, choosing the level of output where: MR = MC. b) The monopoly sets its price at the highest level at which it can sell the profitmaximizing quantity. Table 12.1 uses a numerical example to illustrate the monopoly firm’s output and price decision. MONOPOLY 285 2. The monopoly might earn an economic profit—even in the long run—because the barriers to entry protect the firm from market entry by competitor firms. a) Figure 12.4 illustrates the profit-maximizing choices of a single-price monopolist. b) A monopoly is not guaranteed an economic profit. An economic profit is received only when P > ATC. 286 CHAPTER 12 III. Single-Price Monopoly and Competition Compared A. Comparing the same industry under perfect competition and monopoly reveals the significant differences in these two types of markets. B. Comparing Output and Price 1. Figure 12.5 shows the market outcomes under perfect competition and under monopoly. 2. The market demand curve, D, in perfect competition is the same demand curve that the firm faces in monopoly. 3. The market supply curve, S, in perfect competition is the horizontal sum of the individual firm’s marginal cost curves (S = sum of MC for each firm). This supply curve is also the monopoly’s marginal cost curve. 4. Equilibrium in perfect competition occurs where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied at quantity QC and market price PC. 5. The profit-maximizing equilibrium output for a monopoly QM occurs where MR = MC. Equilibrium price for the monopoly, PM, is obtained from the demand curve, at the profitmaximizing quantity. 6. The monopoly firm produces less output and charges a higher price than a perfectly competitive market. MONOPOLY 287 B. Efficiency and Comparison 1. The monopoly output decision is inefficient. Figure 12.6 shows why this result is so. a) The demand curve, D, is the marginal benefit curve for society, MB, and the competitive market supply curve, S, is the marginal cost curve for society, MC. So competitive equilibrium is efficient because output is produced where MB = MC. b) Monopoly is inefficient because output occurs where MB > MC. c) For all output levels at which MB > MC, a deadweight loss is incurred. So, an increase in output would generate additional MB for society that would exceed the additional MC to society. C. Redistribution of Surpluses Monopoly redistributes a portion of consumer surplus by changing it to producer surplus. D. Rent Seeking 1. The social cost of monopoly may exceed the deadweight loss through an activity called rent seeking, which is any attempt to capture a consumer surplus, a producer surplus, or an economic profit. Rent seeking is not confined to a monopoly. 2. There are two forms of rent seeking: a) Buy a monopoly—expend resources by seeking out the opportunity to buy monopoly rights for a price below the value of the economic profit earned by the monopoly. Example: The buying of taxi cab medallions (a government license) in New York City. b) Create a monopoly—expend resources seeking political influence, such as lobbying legislators to provide preferential market status by restricting domestic competition or enacting tariffs on imports. Example: U.S. steel firms successfully seeking large tariffs placed against imported steel from foreign firms. E. Rent-Seeking Equilibrium 1. There are no barriers to entry in the activity of rent seeking. This fact means that the resources used up in rent seeking are costs which can exhaust the monopoly’s potential economic profit and leave the monopoly owner with only a normal profit. 288 CHAPTER 12 2. However, the outcome is still not efficient, because output does not occur where MB = MC. Figure 12.7 shows the normal profit outcome that results from rent seeking. IV. Price Discrimination A. Price discrimination is the selling of different units of a good or service for different prices. 1. To be able to price discriminate, a firm must: a) Identify and separate different buyer types b) Sell a product that cannot be resold 2. Price discrimination occurs because of different consumer’s willingness to pay for the good. a) Price discrimination does not occur because of cost differences between units produced. b) Not all observed price differences are the result of price discrimination. B. Price Discrimination and Consumer Surplus 1. Price discrimination converts consumer surplus into economic profit. 2. A monopoly firm can price discriminate in different ways: a) Monopoly firms can charge the same buyer a different price for each unit sold. Quantity discounts are an example. However, quantity discounts that reflect lower costs at higher volumes are not price discrimination. b) Monopoly firms can charge different buyers different prices for the same good or service. Giving a lower price on advance purchase airline tickets is an example of this form of price discrimination. C. Profiting by Price Discriminating Figure 12.8 and Figure 12.9 show the same market with a single price monopoly firm and monopoly firm practicing price discrimination, respectively. Comparing these two diagrams shows how price discrimination converts consumer surplus into economic profit for the firm. MONOPOLY 289 290 CHAPTER 12 D. Perfect Price Discrimination 1. Perfect price discrimination occurs if a firm is able to sell each unit of output for the highest price anyone is willing to pay for it. The outcome of perfect price discrimination is characterized by: a) Economic profit increases above that earned by a single-price monopoly firm. b) Output increases to the quantity at which P = MC. c) Deadweight loss is eliminated. 2. Figure 12.10 shows the outcome of perfect price discrimination. E. Efficiency and Rent Seeking with Price Discrimination 1. The more perfectly a monopoly can price discriminate, the closer its output gets to the competitive output where P = MC and the outcome is more efficient. 2. However, this outcome differs from the outcome of perfect competition in two important ways: a) The monopoly firm captures the entire consumer surplus. b) The increase in economic profit attracts even more rent-seeking activity that leads to an inefficient use of resources for society. V. Monopoly Policy Issues A. Gains from Monopoly 1. Monopolies create inefficiency: a) Both single-price and price-discriminating monopolies create deadweight loss. And a price discriminating monopoly converts consumer surplus into producer surplus and economic profit. b) Both types of monopoly also encourage rent-seeking activity, which wastes resources. 2. However, monopoly also brings benefits to society: a) Patents and copyrights provide protection from competition, which lets the monopoly enjoy the profits stemming from product innovation for a longer period of time. This encourages more expenditures on researching/developing new products. b) When production technology exhibits potential for economies of scale or economies of scope, a monopoly firm can produce goods at a lower ATC than what a large number of competitive firms could achieve. (However, because of the deadweight loss, this lower cost of production cannot be fully experienced by society unless the monopoly firm sells the good at a competitive market price.) MONOPOLY 291 B. Regulating Natural Monopoly 1. Where demand and cost conditions create a natural monopoly, a federal, state, or local government agency usually steps in to regulate the price of the monopoly. a. Figure 12.11 shows a the output decisions of a natural monopoly firm and compares two types of outcomes with government regulation with the outcome of no regulation. b. Left alone, the natural monopoly will charge a price and produce at a quantity where MR = MC. Under this outcome, P > MC and the quantity produced is less than the efficient level of output under perfect competition. 2. Regulating a natural monopoly in the public interest sets firm output where MB = MC and P = MC. Setting price equal to marginal cost is called the marginal cost pricing rule, and it results in an efficient use of resources. a) With output occurring where P = MC, the firm’s ATC > P and the monopoly incurs an economic loss. If the monopoly receives a subsidy from the government equal to its economic loss, then taxes must be imposed on some other economic activity. This tax creates deadweight loss in the allocation of resources in the taxed market. b) Where possible, a regulated natural monopoly might be permitted to price discriminate to cover the loss from marginal cost pricing. 3. Another alternative is to produce the quantity at which P = ATC. Setting the price equal to the average total cost is called the average cost pricing rule. a) Output occurs where P > MC, which means that resources are not allocated as efficiently as with a perfectly competitive market. b) However, the inefficiency is less than the unregulated market outcome. Reading Between the Lines The market structure of two internet-based firms are compared to see whether they fit the description of a natural monopoly. e-Bay is a natural monopoly, exhibiting both economies of scale (high fixed costs, low variable costs) and no close substitutes (due to network externalities). Google also exhibits economies of scale for the same reasons as e-Bay. However, Google faces high competition from firms making close substitutes that will likely be developed soon in the fast-paced development of search engine software design. 292 CHAPTER 12 New in the Seventh Edition The Reading Between the Lines looks at the firms e-Bay and Google to illustrate the characteristics of a natural monopoly. Te a c h i n g S u g g e s t i o n s 1. 2. 3. Market Power: Students love a monopoly (if they are the monopolist) Most of your students are taking an economics course because they think it will help them either get a better job or run a better business. Many of your students are aspiring entrepreneurs. You’ve just had them slog through a heavy chapter on perfect competition, the upshot of which is: The firm’s bottom line is miserable. Normal profit maybe the best that many people can achieve but it is not very exciting. This chapter teaches the students how to make some serious entrepreneurial income. Innovate, create a monopoly that produces something that people value much more than the cost of producing it, and price-discriminate as much as possible. Use the monopoly model as a benchmark. Explain (like you did in the case of perfect competition) that although no real-world industry satisfies the full definition of a monopoly market, the behavior of firms in many real world industries can be predicted by using the monopoly model. Mention that this chapter examines the least competitive end of the spectrum of markets, just like Chapter 11 discussed the most competitive end. A Single-Price Monopoly’s Output and Price Decision Marginal revenue curve. Students don’t find the concept of marginal revenue too difficult, but they do need to be clear on the intuition of the MR curve and the reason why MR < P at all levels of quantity for a single-price monopoly. This fact is the central source of the monopoly market outcomes. The classic monopoly diagram. The classic monopoly diagram, Figure 12.4b, provides a good opportunity to tell your students about the contribution of one of the most brilliant economists of the 20th century, Joan Robinson. This diagram first appeared in her book, The Economics of Imperfect Competition, published in 1933 when she was just 30 years old. (You can learn more about Joan Robinson at http://cepa.newschool.edu/het/profiles/robinson.htm). Women are still not attracted to economics on the scale that they’re attracted to most other disciplines, so the opportunity to talk about an outstanding female economist shouldn’t be lost. Joan Robinson was a formidable debater and reveled in verbal battles, a notable one of which was with Paul Samuelson on one of her visits to MIT. Anxious to make and illustrate a point, Samuelson asked Robinson for the chalk. Monopolizing the chalk and the blackboard, the unyielding Robinson snapped, “Say it in words young man.” Samuelson meekly obeyed. This story illustrates Joan Robinson’s approach to economics: work out the answers to economic problems using the appropriate techniques of math and logic, but then “say it in words.” Don’t be satisfied with formal argument if you don’t understand it. Your students will benefit from this story if you can work it into your class time. Single-Price Monopoly and Competition Compared: Monopoly is always inefficient. The inefficiency of monopoly is one of the key propositions in this chapter. When a monopoly firm operates where MR = MC, it chooses an output level where P > MR and P > MC. A single-price monopoly under-produces and creates a deadweight loss. Rent seeking uses further resources, so potentially the social cost of monopoly is the sum of the deadweight loss and the economic profit that a monopoly might earn. Price Discrimination by a monopoly firm is relatively less inefficient, but it is still not as efficient as perfect competition. MONOPOLY 293 4. Adam Smith described the situation thus: “People in the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in some contrivance to raise prices. Monopoly Policy Issues A quick introduction. The treatment of monopoly policy here is designed for the instructor who wants to cover the topic briefly and at this point in the course. Chapter 14 provides a more extensive treatment of regulation and antitrust law. You can cover that chapter, in whole or part, right now if you want to do more on the topic. The Big Picture Where we have been Chapter 11 on perfect competition and Chapter 12 on monopoly have shown the student the two opposite ends of the market spectrum (relevant to market power) and contrasted the performance of these ideal market types. The chapters have also deepened the student’s understanding of the efficiency of competitive markets and the source of inefficiency of monopoly. Where we are going Chapter 13 describes firms and industries in monopolistic competition and oligopoly and fills in the middle of the spectrum. Chapter 14 expands on the final section of the present chapter by reviewing regulation and antitrust law. O ve r h e a d Tr a n s pa r e n c i e s Transparency 73 Text figure Figure 12.2 Transparency title Demand and Marginal Revenue 74 Figure 12.3 Marginal Revenue and Elasticity 75 Figure 12.4 A Monopoly’s Output and Price 76 Figure 12.5 Monopoly’s Smaller Output and Higher Price 77 Figure 12.6 Inefficiency of Monopoly 78 Figure 12.9 Price Discrimination 79 Figure 12.10 Perfect Price Discrimination 80 Figure 12.11 Regulating a Natural Monopoly 81 Table 12.1 A Monopoly’s Output and Price Decision Electronic Supplements MyEconLab MyEconLab provides pre- and post-tests for each chapter so that students can assess their own progress. Results on these tests feed an individualized study plan that helps students focus their attention in the areas where they most need help. 294 CHAPTER 12 Instructors can create and assign tests, quizzes, or graded homework assignments that incorporate graphing questions. Questions are automatically graded and results are tracked using an online grade book. PowerPoint Lecture Notes PowerPoint Electronic Lecture Notes with speaking notes are available and offer a full summary of the chapter. PowerPoint Electronic Lecture Notes for students are available in MyEconLab. Instructor CD-ROM with Computerized Test Banks This CD-ROM contains Computerized Test Bank Files, Test Bank, and Instructor’s Manual files in Microsoft Word, and PowerPoint files. All test banks are available in Test Generator Software. Additional Discussion Questions 1. 2. The double-edged sword of a natural monopoly. Emphasize how economic analysis reveals the social benefits and costs of an industry characterized by a downward sloping, long run ATC curve. Ask the student the following questions: What is the characteristic of the monopoly market that allows a natural monopoly to potentially produce output at the lowest possible ATC? The student should see that a lack of competition allows the firm to potentially serve the entire market at a lower unit cost than if it had to share the market with any other number of firms. A multi-firm market would be forced to produce at a higher ATC. What is the characteristic of a monopoly market that allows a natural monopoly to potentially charge consumers a price premium above long-run ATC? If the natural monopoly has the freedom to set its own price, the student should identify the lack of competition that prevents the consumer from benefiting from production actually occurring at the lowest ATC. On the one hand, the lack of competition is the only way to allow society to enjoy a (potentially) more efficient allocation of resources, yet it also allows the firm to extract consumer surplus while generating an inefficient resource allocation—a “double-edged sword.” Troubles with price discrimination: The ethics of scalping. Get the students to address the realities of arbitrage in secondary markets that arise when the primary seller of a good refuses to price discriminate. Is it in society’s best interest (economically efficient) to allow the scalping of tickets? The students should see that ticket scalping is just a form of price discrimination, which is a business practice shown in the text to increase the level of efficiency in resource allocation within a monopoly market context. Why do the original ticket sellers refuse to price discriminate like the scalpers? There are many possible reasons: The original seller of the tickets (usually the music group giving the concert or the ticket sellers that are under direct contract for them) may want to avoid the reputation of charging different prices to different people, or different prices at different time intervals before the concert. The original seller may not have the ability to distinguish between high and low demand customers, like those who sell the tickets standing outside the doors on the day of the concert MONOPOLY 295 The original sellers may be very risk averse and prefer to sell every ticket well in advance of the concert date, based on the expectations of sales potential made with the best available information at the time. However, information about the actual demand for a concert becomes clearer as the concert date draws nearer and the equilibrium price for a ticket may change significantly. Scalpers must gamble that ticket prices will increase when it eventually becomes clear that demand for the event is relatively inelastic. They bear the risk that the original ticket seller would not bear: that the ticket prices may also decrease if it is revealed that demand for the event is relatively elastic. Is it “fair” to allow scalping of concert tickets? Remind the students that the practice of price discrimination can increase monopoly profits for the resellers while simultaneously increasing efficiency for society. Remind them of the principle of opportunity cost and ask them to consider how much efficiency they are willing to give up in the name of “fairness.” If it is unfair to scalp tickets because of the way price discrimination transfers consumer surplus to producer surplus, then what about other forms of price discrimination? Ask the students to consider the following scenarios. They should understand that in each case, there is an identifiable group of consumers who have a different willingness to pay for the product or service mentioned. 3. 4. If the costs of projecting a movie are the same at all times of day, why are matinee movie prices lower than evening movie prices for the exact same movie in the exact same theater? Why do movie theaters often give students discounts? If the cost of publication is the same for all potential subscribers, then why do magazines and newspapers offer students discounts on subscription prices? If the cost of serving beverages and supplying entertainment (live bands) is the same for both men and women, then why do bars and clubs offer “Ladies Night” where women get free drinks or pay no cover charge? If the cost of serving food and beverages is the same for all diners, then why do seniors get a price break from restaurants for the exact same meals? Why is a monopoly firm motivated to operate at the socially inefficient level of output and steal away consumer surplus? The lack of competition from barriers to entry gives the monopoly firm the ability to exercise market power and set price. Market power drives a wedge between the price the monopoly firm receives for selling an additional unit and the marginal revenue received from selling that additional unit. Selling fewer units creates a deadweight loss, some of which is borne by the monopoly firm. However, it more than makes up for its share of lost producer surplus by extracting a larger amount of consumer surplus. How would you measure the inefficiency of a monopoly? The students should see that the lost potential for consumer and producer surplus could be calculated as deadweight loss, but that is only part of the total loss of benefits. Ask the students: Is there more to the inefficiency of a monopoly than meets the eye? If you are rather brave, you may want to ask the students to play the following game: Show the class a fresh, real five-dollar bill. Announce that it is a monopoly profit that anyone in class can receive simply by submitting the highest, non-zero price bid for it. Mention that even if the highest bid is only one penny, then that person will receive the five-dollar bill. However, everyone else that submits a bid must also pay you the value of that bid, regardless of whether they are successful. In the case of a tie for highest bid, a run-off bidding contest among the tied high bidders will occur, but their first bid still stands as a debt to you, the holder of the monopoly profit. How much would YOU bid for this monopoly profit? Ask the students to write down on a small piece of paper their name and the price he or she is willing to bid for the five-dollar bill. They 296 CHAPTER 12 may write a bid of zero cents, but they will not get a chance to win. Announce that you will collect the money from them later (you will have their name and their bid). After collecting the bids, roughly tally them up and announce the winning bid, as well as the total sum of the bids to be collected. There are two possible scenarios to the outcome of this auction: There is one high bidder, and this bid is usually very close to the monopoly profit offered for sale—there are usually one or two students who want to signal their “devil-may-care” attitude or signal their status as a relatively wealthy student who can afford to play extravagant games. There is a tie between two or more students. The resulting run-off bidding is usually very high, because each of the remaining students hasn’t yet fully appreciated the economic notion of sunk costs. In this latter case, do not be surprised if the winning bid is more than five dollars, as the “winner” wants desperately not to lose the full amount of his or her initial bid. What is the total opportunity cost of the resources used to pursue monopoly profits? Point out that the bids represent the resources people use (usually through lobbying efforts) to pursue a monopoly market position by convincing government to restrict competition. Ultimately, only one person wins, but all contenders expend resources in the pursuit. That is why all losing bidders had to pay their bid price. Can we compare the value of lost output in other markets that could have been produced against the value of those goods and services produced specifically for pursuing a monopoly? Emphasize that the goods and services that were used to pursue a monopoly would not have been chosen for production if the monopoly profit hadn’t been offered up for sale in the first place. That is how we can know that rent seeking is inefficient—there was a decline in net benefits for society from forgone production of higher-valued goods. After the discussion is over, give the highest bidder the five-dollar bill in exchange for the bid he or she pledged. (You were warned about having to be brave!) If the highest bid is over five dollars, just state that you will forgive the student his or her debt and call it a wash. Then announce that the other bidders are also off the hook, as you were just trying to make the scenario as realistic as possible. Many sighs of relief will be heard. MONOPOLY 297 Answ ers to the Review Quizzes Page 267 1. A single-price monopoly firm chooses to maximize profits by producing at an output level where marginal cost equals marginal revenue (MR = MC). 2. The market demand curve is the monopolist firm’s demand curve. The demand curve reveals that the profit-maximizing level of output is associated with a maximum price that the monopolist firm can charge and sell that level of output. 3. The MR < P at every level of output. When the profit-maximizing monopoly firm chooses output where MR = MC, MC must be below price: (MR = MC) < P. 4. Barriers to entry prevent the monopoly firm from enduring the pressure of competition, and allow it to choose the quantity of output that is associated with the profit-maximizing market price. This allows a monopoly firm to potentially enjoy positive economics profits, even in the long run. 1. The market supply curve for a competitive industry is the horizontal summation of the individual firm’s marginal cost curves. Equilibrium output level is determined where market supply curve intersects the market demand curve, and market price equals marginal cost. Equilibrium output for a single-price monopoly is determined by the intersection of its marginal cost curve and the marginal revenue curve. Marginal revenue is always less than price, which means that MR = MC at a lower level of output than P=MC, and market price exceeds the marginal cost. Compared to a perfectly competitive firm, a monopoly restricts its output and charges a higher price. 2. The monopoly raises price by lowering quantity offered for sale. This raises the price consumers must pay for the good compared to the competitive market price. This difference in price multiplied by the quantity the monopolist sells represents the amount of consumer surplus that is transferred to producer surplus. 3. In a competitive market, the supply curve represents marginal cost to society, and the demand curve represents the marginal benefits to society. The perfectly competitive market is efficient because production occurs where supply equaled demand (MB = MC). The monopolist is inefficient because price exceeds marginal cost at all levels of output. When the monopoly equates MC = MR to choose the profit-maximizing level of output, it charges a price from the demand curve that is greater than marginal cost, which means MB > MC. Consumer and producer surplus are not maximized and society suffers a dead weight loss. 4. Rent seeking is any attempt to capture consumer surplus, producer surplus, or economic profit. There are two forms of rent seeking activity to pursue a monopoly status: i) Buying a monopoly, where a person expends resources seeking to purchase monopoly rights for a price slightly less than the monopoly profits, or ii) Creating a monopoly, where a person expends resources seeking political influence, such as lobbying legislators to provide preferential market status by restricting domestic competition or enacting tariffs on imports. The resources expended in rent seeking can be equal to (or even greater than) the economic profit that a monopoly status would create for the owner. 1. Price discrimination is the practice of selling different units of a good or service for different prices. In order for a monopoly to practice price discrimination, a monopoly must be able to: i) Page 271 Page 274 298 CHAPTER 12 identify and separate different buyer types, and ii) sell a product that cannot be resold. The key idea to price discrimination is to charge different consumers different prices, according to their willingness to pay for the good. This transfers potential consumer surplus under a single-price scenario into producer surplus, raising monopoly profits. 2. When a monopoly price discriminates, it charges different prices to different consumers and transfers the consumer surplus that would appear under a single-price scenario into producer surplus, increasing monopoly profits. 3. Perfect price discrimination is when a monopoly charges each consumer the maximum price he or she is willing to pay. This transfers the entire potential consumer surplus to producer surplus. The monopoly increases its profits compared to charging a single-price to all customers and produces at a higher level of output, where price equals marginal cost. This outcome achieves efficiency by eliminating the deadweight loss relative to a single-price monopoly outcome. 4. A consumer’s elasticity of demand for airline tickets tends to increases with the amount of advance time they are willing to endure for purchasing them. The airline companies make airline tickets non-transferable, preventing consumers with high elasticity of demand form reselling their less expensive tickets to those consumers with inelastic demand. This allows the airlines to charge different prices to different groups of consumers, according to their willingness to pay. 1. First, monopolies might encourage product innovation. Patents and copyrights provide protection from competition and let the monopoly enjoy the profits stemming from innovation for a longer period of time. Second, monopolies can take advantage of economies of scale and scope. A monopoly’s access to different technology stemming from larger production runs can generate marginal costs that are lower than a supply curve of a competitive industry over the larger range of output. This means the monopoly can produce more output and charge a lower price than would a firm in a perfectly competitive industry. 2. Economies of scale occur if the firm’s ATC declines as it expands output. Examples given in the text are public utilities such as water and natural gas, although the economies of scale may occur only in distribution and not production. Economies of scope take place if the firm’s ATC declines as the number of different goods produced increases. Examples given in the text are burger and fry production at fast food restaurants, the manufacture of household appliances and the refining of petroleum. 3. Monopoly markets may encourage greater product innovation than under perfect competition. Patents and copyrights provide protection from competition and let the monopoly enjoy the profits from innovation for a longer period of time. 4. Regulating the actions of a natural monopoly in the public interest implies setting the level of output where the MB = MC, and the monopoly must set its price equal to marginal cost. This is type of regulation is called the marginal cost pricing rule, resulting in a maximum of total consumer and producer surplus in the market. However, when the monopoly price equals marginal cost, the ATC exceeds the price and the monopoly suffers an economic loss. The monopoly will exit the market unless it receives a subsidy to return it to zero economic profit. Yet this subsidy must be raised through imposing taxes on other economic activity, which creates deadweight loss and prevents efficient resource allocation in the markets affected by the tax. 5. For a natural monopoly, marginal cost is less than average cost at all levels of output in the market. The marginal cost pricing rule will generate greater consumer surplus and less Page 277 MONOPOLY 299 producer surplus because P = MC at a higher level of output than when P = ATC. However, when P = MC, ATC exceeds price and the monopoly suffers an economic loss (negative producer surplus). The monopoly will only stay in business if it receives a subsidy to make up for the economic loss, returning it to a zero producer surplus (normal profit) condition. Yet this subsidy must be provided through taxing other markets, causing inefficient resource allocations in those markets. While the monopoly market will be efficient (MB = MC) and not experience a deadweight loss, the other markets affected by the tax will experience an increase in dead weight loss. The average cost pricing rule generate the same producer surplus as a subsidized monopoly under a marginal cost pricing rule, but the consumer surplus will be lower because P = ATC at a lower level of output than P = MC. Deadweight loss will occur in this monopoly market because MB no longer equals MC. This result occurs because the monopoly produces where P = ATC and ATC exceeds MC at this level of output. 300 CHAPTER 12 Answ ers to the Problems 1. a. b. 2. a. b. 3. a. b. c. d. e. 4. a. b. Minnie’s total revenue schedule lists the total revenue at each quantity sold. For example, Minnie’s can sell 1 bottle for $8 a bottle, which is $8 of total revenue at the quantity 1 bottle. Minnie’s marginal revenue schedule lists the marginal revenue that results from increasing the quantity sold by 1 bottle. For example, Minnie’s can sell 1 bottle for a total revenue of $8. Minnie’s can sell 2 bottles for $6 each, which is $12 of total revenue at the quantity 2 bottles. So by increasing the quantity sold from 1 bottle to 2 bottles, marginal revenue is $4 a bottle ($12 minus $8). Burma’s total revenue schedule lists the total revenue at each quantity sold. For example, Burma’s can sell 2 rubies for $700 each, which gives it a total revenue of $1,400 at the quantity 2 rubies. Burma’s marginal revenue schedule lists the marginal revenue that results from increasing the quantity sold by 1 ruby. For example, Burma’s can sell 1 ruby for $900, which is total revenue of $900 at the quantity of 1 ruby. Burma’s can sell 2 rubies for $700 each, which is $1,4000 of total revenue at the quantity 2 rubies. So by increasing the quantity sold from 1 to 2 rubies, marginal revenue is $500 per ruby ($1,400 minus $900). Marginal cost is the increase in total cost that results from increasing output by 1 unit. When Minnie’s increases output from 1 bottle to 2 bottles, total cost increases by $4, so the marginal cost is $4 a bottle. Minnie’s profit-maximizing output is 1.5 bottles. The marginal cost of increasing the quantity from 1 bottle to 2 bottles is $4 a bottle ($7 minus $3). That is, the marginal cost of the 1.5 bottles is $4 a bottle. The marginal revenue of increasing the quantity sold from 1 bottle to 2 bottles is $4 ($12 minus $8). So the marginal revenue from 1.5 bottles is $4 a bottle. Profit is maximized when the quantity produced makes the marginal cost equal to marginal revenue. The profit-maximizing output is 1.5 bottles. Minnie’s profit-maximizing price is $7 a bottle. The profit-maximizing price is the highest price that Minnie’s can sell the profit-maximizing output of 1.5 bottles. Minnie’s can sell 1 bottle for $8 and 2 bottles for $6, so it can sell 1.5 bottles for $7 a bottle. Minnie’s economic profit is $5.50. Economic profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals price ($7 a bottle) multiplied by quantity (1.5 bottles), which is $10.50. Total cost of producing 1 bottle is $3 and the total cost of producing 2 bottles is $7, so the total cost of producing 1.5 bottles is $5. Profit equals $10.50 minus $5, which is $5.50. Minnie’s is inefficient. Minnie’s charges a price of $7 a bottle, so consumers get a marginal benefit of $7 a bottle. Minnie’s marginal cost is $4 a bottle. That is, the marginal benefit of $7 a bottle exceeds Minnie’s marginal cost. Burma’s marginal cost when output is increased from 1 ruby to 2 rubies a day is $80. The total cost of producing 1 ruby is $1,220 and the total cost of producing 2 rubies is $1,300, so the marginal cost of an additional ruby is $80. Burma’s profit-maximizing output is 2.5 rubies a day. The marginal cost of increasing the quantity from 2 rubies to 3 rubies is $100 ($1,300 minus $1,400). That is, the marginal cost of producing the 2.5th ruby is $100. The marginal revenue of increasing the quantity sold from 2 to 3 rubies is $100 ($1,400 minus $1,500). So the marginal revenue from selling the 2.5th ruby is $100. Profit is maximized when the quantity produced makes the marginal cost equal to marginal revenue. The profit-maximizing output is 2.5 rubies per day. MONOPOLY 301 c. d. f. 5. a. b. c. d. e. 6. a. b. c. d. Burma’s profit-maximizing price is $600 a ruby. The profit-maximizing price is the highest price that Burma’s can sell the profit-maximizing output of 2.5 rubies a day. Burma’s can sell 2 rubies for $700 each and 3 rubies for $500 each, so it can sell 2.5 rubies for $600 each. Burma’s economic profit is $150. Economic profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals price ($600 a ruby) multiplied by quantity (2.5 rubies), which is $1,500. Total cost of producing 2 rubies is $1,300 and the total cost of producing 3 rubies is $1,400, so the total cost of producing 2.5 rubies is $1,350. Profit equals $1,500 minus $1,350, which is $150. Burma’s is inefficient. Burma’s charges a price of $600 a ruby, so consumers get a marginal benefit of $600 a ruby. Burma’s marginal cost is $100 a ruby. That is, consumers’ marginal benefit exceeds Burma’s marginal cost. The profit-maximizing quantity is 150 newspapers a day and price is 70 cents a paper. Profit is maximized when the firm produces the output at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue. Draw in the marginal revenue curve. It runs from 100 on the y-axis to 250 on the x-axis. The marginal revenue curve cuts the marginal cost curve at the quantity 150 newspapers a day. The highest price that the publisher can sell 150 newspapers a day is read from the demand curve. The daily total revenue is $105 (150 papers at 70 cents each). Demand is elastic. Along a straight-line demand curve, demand is elastic at all prices above the midpoint of the demand curve. The price at the midpoint is 50 cents. So at 70 cents a paper, demand is elastic. The consumer surplus is $22.50 a day and the deadweight loss is $15 a day. Consumer surplus is the area under the demand curve above the price. The price is 70 cents, so consumer surplus equals (100 cents minus 70 cents) multiplied by 150/2 papers a day, which is $22.50 a day. Deadweight loss arises because the publisher does not produce the efficient quantity. Output is restricted to 150, and the price is increased to 70 cents. The deadweight loss equals (70 cents minus 40 cents) multiplied by 100/2. The newspaper will not want to price discriminate unless it can find a way to prevent sharing and resale of the newspaper from those who are charged a lower price to those who are charged a higher price. The profit-maximizing quantity is 2 cups an hour. The price is $3 a cup. Profit is maximized when the firm produces the output at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue. Draw in the marginal revenue curve. It runs from 4 on the y-axis to 4 on the x-axis. The marginal revenue curve cuts the marginal cost curve at the quantity 2 cups an hour. The highest price at which the coffee shop can sell 2 cups an hour is read from the demand curve. Economic profit per cup is $1 ($3 minus $2). The quantity produced and sold is 2 cups. So economic profit is $2 a day. The consumer surplus is $1.00 a day and the deadweight loss is $0.50 a day. The efficient quantity is 3 cups an hour. The quantity at which marginal cost equals marginal benefit (the intersection of the marginal cost curve and the demand curve, which show marginal benefit). 302 CHAPTER 12 e. 7. a. b. c. 8. a. b. c. Consumer surplus is the area under the demand curve above the price. The price is $3, so consumer surplus equals ($4 minus $3) multiplied by 2/2cups a day, which is $1.00 a day. Deadweight loss arises because the coffee shop does not produce the efficient quantity. Output is restricted to 2 cups an hour, and the price is increased to $3 a cup. The deadweight loss equals ($3 minus $2) multiplied by 1/2, which is $0.50. The coffee shop will want to price discriminate. The cup of coffee is not really an item that can be resold, so the coffee shop might offer 1 coffee a day for $3.00 and a second cup for $2.50 and stamp the back of the hand of each customer who buy 1 coffee a day. Or it might offer coffee to students at $2.50 and senior citizens at $2.00. The firm will produce 2 cubic feet a day and sell it for 6 cents a cubic foot. Deadweight loss will be 4 cents a day. Draw in the marginal revenue curve. It runs from 10 on the y-axis to 2.5 on the x-axis. The profit-maximizing output is 2 cubic feet at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. The price charged is the highest that people will pay for 2 cubic feet a day, which is 6 cents a cubic foot. The efficient output is 4 cubic feet, at which marginal cost equals price (marginal benefit). So the deadweight loss is (4 minus 2 cubic feet) multiplied by (6 minus 2 cents)/2. The firm will produce 3 cubic feet a day and charge 4 cents a cubic foot. Deadweight loss is 1 cent a day. If the firm is regulated to earn only normal profit, it produces the output at which price equals average total cost—at the intersection of the demand curve and the ATC curve. The firm will produce 4 cubic feet a day and charge 2 cents a cubic foot. There is no deadweight loss. If the firm is regulated to be efficient, it will produce the quantity at which price (marginal benefit) equals marginal cost—at the intersection of the demand curve and the marginal cost curve. The firm will produce 1.5 cubic feet a day and sell it for 7 cents a cubic foot. Deadweight loss will be 2.25 cents a day. Draw in the marginal revenue curve. It runs from 10 on the y-axis to 2.5 on the x-axis. The marginal cost doubles to 4 cents and the marginal cost curve shifts up to cut the y-axis at 4 cents. The profit- maximizing output is 1.5 cubic feet at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. The price charged is the highest that people will pay for 1.5 cubic feet a day, which is 7 cents a cubic foot. The efficient output is 3 cubic feet, at which marginal cost equals price (marginal benefit). So the deadweight loss is (3 minus 1.5 cubic feet) multiplied by (7 cents minus 4 cents)/2. The firm will produce 2 cubic feet a day and charge 6 cents a cubic foot. Deadweight loss is 1 cent a day. If the firm is regulated to earn only normal profit, it produces the output at which price equals average total cost—at the intersection of the demand curve and the ATC curve. The firm will produce 3 cubic feet a day and charge 4 cents a cubic foot. There is no deadweight loss. If the firm is regulated to be efficient, it will produce the quantity at which price (marginal benefit) equals marginal cost—at the intersection of the demand curve and the marginal cost curve. MONOPOLY 303 Additional Problems 1. Dolly’s Diamond Mines, a single-price monopoly, faces the following demand schedule for industrial diamonds: Price Quantity (dollars demanded per pound) 2. (pounds per day) a. 2,200 5 2,000 6 1,800 7 1,600 8 1,400 9 1,200 10 Calculate Dolly’s total revenue schedule. b. Calculate its marginal revenue schedule. Dolly’s Diamond Mines in problem 1 has the following total cost: Quantity Total produced cost (pounds per day) (dollars) 5 8,000 6 9,000 7 10,200 8 11,600 9 13,200 10 15,000 Calculate the profit-maximizing levels of a. Marginal cost 3. b. Marginal revenue c. Output d. Price e. Economic profit f. Does Dolly’s Mines use resources efficiently? Explain your answer. The figure illustrates the situation facing the publisher of the only newspaper containing local news in an isolated community. The publisher’s marginal cost for the new plant is constant at 20 cents per copy printed. a. What quantity of newspapers will maximize the publisher’s profit? b. What price will the publisher charge for a daily newspaper? c. What is the publisher’s daily total revenue? d. At the price charged for a newspaper, is the demand for newspapers elastic or inelastic? Why? 304 CHAPTER 12 4. 5. In the monopoly newspaper market described in problem 3, a. What is the efficient quantity of newspapers to print each day? Explain your answer. b. What is the consumer surplus of the readers of the newspaper? c. What is the deadweight loss created by the monopoly newspaper publisher? What is the maximum value of resources that will be used in rent seeking to acquire Dolly’s monopoly in problem 1? Considering this loss, what is the total social cost of Dolly’s monopoly? MONOPOLY 305 Solutions to Additional Problems 1. a. b. 2. a. b. c. d. e. f. 3. a. b. c. d. Dolly’s total revenue schedule lists the total revenue at each quantity sold. For example, Dolly’s can sell 10 pounds for $1,200 a pound, which gives it a total revenue of $12,000 at the quantity 10 pounds. Dolly’s marginal revenue schedule lists the marginal revenue that results from increasing the quantity sold by 1 pound. For example, Dolly’s can sell 5 pounds for $2,200 each, which is total revenue of $11,000 at the quantity of 5 pounds. Dolly’s can sell 6 pounds for $2,000 each, which is $12,000 of total revenue at the quantity 6 pounds. So by increasing the quantity sold from 5 pounds to 6 pounds, marginal revenue is $1,000 a pound ($12,000 minus $11,000). Dolly’s marginal cost is $1,000 a pound. The marginal cost of increasing the quantity from 5 pounds to 6 pounds is $1,000 a pound ($9,000 minus $8,000). That is, the marginal cost of the 5.5 pounds is $1,000 a pound. Dolly’s marginal revenue is $1,000 a pound. The marginal revenue of increasing the quantity sold from 5 pounds to 6 pounds is $1,000 ($12,000 minus $11,000). So the marginal revenue from 5.5 pounds is $1,000 a pound. Dolly’s profit-maximizing output is 5.5 pounds. The marginal cost of increasing the quantity from 5 pounds to 6 pounds is $1,000 a pound ($9,000 minus $8,000). That is, the marginal cost of the 5.5 pounds is $1,000 a pound. The marginal revenue of increasing the quantity sold from 5 pounds to 6 pounds is $1,000 ($12,000 minus $11,000). So the marginal revenue from 5.5 pounds is $1,000 a pound. Profit is maximized when the quantity produced makes the marginal cost equal to marginal revenue. The profit-maximizing output is 5.5 pounds. Dolly’s profit-maximizing price is $2,100 a pound. The profit-maximizing price is the highest price that Dolly’s can sell the profit-maximizing output of 5.5 pounds. Dolly’s can sell 5 pounds for $2,200 and 6 pounds for $2,000, so it can sell 5.5 pounds for $2,100 a pound. Dolly’s economic profit is $3,050. Economic profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals price ($2,100 a pound) multiplied by quantity (5.5 pounds), which is $11,550. Total cost of producing 5 pounds is $8,000 and the total cost of producing 6 pounds is $9,000, so the total cost of producing 5.5 pounds is $8,500. Profit equals $11,550 minus $8,500, which is $3,050. Dolly’s is inefficient. Dolly’s charges a price of $2,100 a pound, so consumers get a marginal benefit of $2,100 a pound. Dolly’s marginal cost is $1,000 a pound. That is, the marginal benefit of $2,100 a pound exceeds Dolly’s marginal cost. The profit-maximizing output is 200 newspapers a day. Profit is maximized when the firm produces the output at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue. Draw in the marginal revenue curve. It runs from 100 on the y-axis to 250 on the x-axis. The marginal revenue curve cuts the marginal cost curve at the quantity 200 newspapers a day. The price charged is 60 cents a paper. The highest price that the publisher can sell 200 newspapers a day is read from the demand curve. The daily total revenue is $120 (200 papers at 60 cents each). Demand is elastic. 306 CHAPTER 12 Along a straight-line demand curve, demand is elastic at all prices above the midpoint of the demand curve. The price at the midpoint is 50 cents. So at 60 cents a paper, demand is elastic. 4. a. b. c. 5. The efficient quantity is 400 newspapers—the quantity that makes marginal benefit (price) equal to marginal cost. With 400 newspapers available, people are willing to pay 20 cents for a paper. To produce 400 newspapers, the publisher incurs a marginal cost of 20 cents a paper. The consumer surplus is $40 a day. Consumer surplus is the area under the demand curve above the price. The price is 60 cents, so consumer surplus equals (100 cents minus 60 cents) multiplied by 200/2 papers a day, which is $40 a day. The deadweight loss is $40 a day. Deadweight loss arises because the publisher does not produce the efficient quantity. Output is restricted to 200, and the price is increased to 60 cents. The deadweight loss equals (60 cents minus 20 cents) multiplied by 200/2. The maximum that will be spent on rent seeking is $3,050 a day—an amount equal to Dolly’s economic profit. The total social cost equals the deadweight loss plus the amount spent on rent seeking. To calculate the deadweight loss, first calculate the efficient output—the intersection point of the demand curve (marginal benefit curve) and the marginal cost curve. Do this by finding the equations to the two curves and solving them. The efficient output is 8.25 pounds. The deadweight loss equals $1,512.50. The loss to society is $4,562.50 ($3,050 plus $1,512.50). MONOPOLY 307