Running Head: JUVENILE JUSTICE

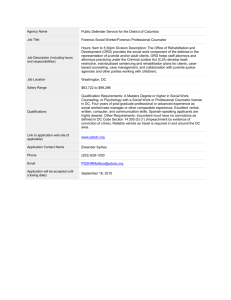

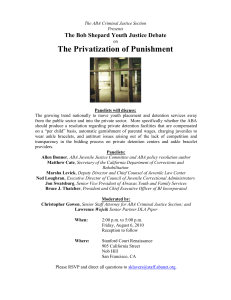

advertisement