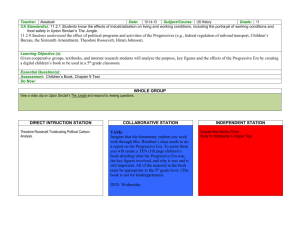

The Progressive Era - U-System

advertisement