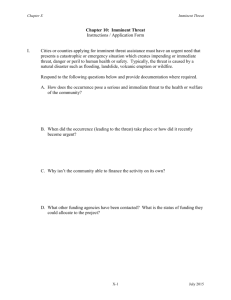

computer crime chapter - Berkman Center for Internet and Society

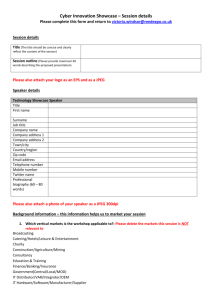

advertisement