On Walt Whitman, Bette Davis,

advertisement

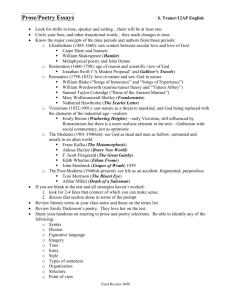

1 On Walt Whitman, Bette Davis, and the Neglect Of Poetry Trey N. Magee In the contemporary world of poetry, there is a debate regarding the relationship between the poet and the public, a relationship where the poet is torn between the need to find an audience and a desire to write, uncompromisingly, the best he or she can with a total disregard for the consequences of critical opinion. In his essay “On the Neglect of Poetry in the United States,” Louis Simpson contends that the poet should neither be constrained nor corrupted by trying to please the public. Only by disregarding the public can the poet remain true. He goes on to insist that poetry itself should stand alone, that to incorporate it with other art forms, especially performance art, in a quest to broaden poetry’s appeal is useless. Great poetry, he says, needs no assistance.1 While certain aspects of Simpson’s argument certainly have merit, it is in his negative assessment of the role other art forms play in expanding poetry’s appeal that he falters. Today, great poetry does indeed need assistance. To begin with, the intellectual audience of today grew up with poetry as a fringe element of its education and, as a consequence, poetry became increasingly esoteric and lost its relevance as an art form of much importance to the educated public. Second, the great poets of the past to whom Simpson refers, Chaucer, Milton, Whitman, et al, unlike the poets of today, never had to compete with the new artistic mediums of modern culture—a competition Simpson admits the poet would lose. Finally, no matter how great a work of poetry may be, it cannot regain its cultural importance if it remains locked within the confines of academia. Today’s audience of general intellectual interest, of which I am a part, grew with the notion that poetry was a noble and beautiful art form but never seemed to get past that point. We were not schooled in poetry’s history, rhyme, or meter and could not venture to tell you why a poem was good, fair, or poor, much less great. We simply were not exposed to poetry enough to acquire the skills needed to appreciate what was deemed “great.” Poetry mainly seemed “difficult” at best and downright bizarre at worst. Basically, it was something that had to be slugged through and endured. Robert Frost was an exception whose “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening “ gave a glimmer of hope to the poetically challenged fifth grader. That same fifth grader was soon thrown hopelessly back into apathy with Wallace Steven’s puzzling, yet whimsical, “Bantams in Pine-Woods,” a great poem in our young minds 2 for no other reason than that our teacher said so. No other explanation needed. And yet an explanation was needed; without one we stopped caring, and poetry ceased to matter. We tend to neglect things that do not matter. Make no mistake, other subjects were deemed just as dull and difficult by our preoccupied little minds, yet they, unlike poetry, were meant to be mastered. We couldn’t make it to the sixth grade without our math and English language skills. And while we were being escorted to “art” class, where the wonders of painting awaited, or being read to from Dickens and Twain, I can venture to say that our sixth grade teacher could not have cared less whether we knew the difference between a sonnet and a nursery rhyme. This indifference was indoctrinated then and remains now. How can we overcome it? How can we re-ignite an interest in something that has the capacity to touch us deeply and speak so eloquently about our lives? In short, how can we begin the process of rediscovering poetry? In his essay, Mr. Simpson thinks that great poetry alone will set us on the road to rediscovery: write it, and we will come. It is both simplistic and quixotic to believe that “the way to overcome the present neglect of poetry is to write great poems.”2 He does not take into consideration that the majority of the educated public no longer knows what great poetry is. That knowledge was not part of our education. He seems to think that we inhabit the same world he does—a world in which the neglect of poetry has more to do with mediocrity than with ignorance. Sadly, we are not part of his world, and ignorance plays a bigger role in poetry’s fall than Mr. Simpson may realize. I do agree with Simpson in that we must be exposed to great poetry in order to start caring. That is not the issue. The issue is what, exactly, has the capacity to bring us back to this great poetry? A great poem, written by a poet with no concern other than beauty, meaning, and truth, is not going to miraculously appear at our bedside. Something has to get it there; something has to pique our atrophied interest. This is where other art forms can have a positive effect. Dana Gioia expressed this issue in his essay “Can Poetry Matter?” Gioia writes that integrating poetry with the mediums of other art forms, such as music, has the potential to reach that critical, culturally influential audience which would otherwise remain distant to poetry. This audience, representing “our cultural intelligensia,” is comprised of the people who support the arts and concern themselves with their influence on our society. It is also the audience poetry has lost but which remains faithful to other art forms. The possibility of manipulating the relative popularity of these other art forms to bridge the gap and bring poetry back into the world of influential art is a repugnant idea to Simpson. While declaring it a noble thought, he ultimately dismisses the idea by saying you can’t make people like poetry simply by exposing them to it—kind of like the old adage, “you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink.”3 Simpson insists that “only a great poem, a 3 poem it remembers” can do that. That may be, but no one will be able to remember a poem unless he or she can first encounter it. Simpson and I do agree upon the role of poetry as performance art. I too, believe that a great poem does not have to rely on gimmicks to find or keep an audience. Poetry and theater are distinct entities and one has the tendency to distract from the other when combined. My purpose here is to suggest possibilities of creating a broader appeal for poetry by utilizing other, more popular art forms, and not to advocate the fusion of poetry with those art forms. Integrating poetry with these other art forms can expose individuals to its beauty in ways that poetry alone has failed to do. I am lucky enough to have benefited from such a situation. One sleepless night many years ago, I was watching an old Bette Davis film, Now Voyager. At a turning point in the film, a Whitman poem was read. It was a very short, seemingly ephemeral poem, and yet I was struck by its message and beauty. The classic film itself paled in comparison to Whitman’s haunting poem. Unable to forget it, I soon found myself scouring the shelves of the public library in search of a poem whose title I didn’t know. It wasn’t long before I stumbled upon an old edition of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. There, buried in the middle, was “The Untold Want.” I had found it. With that single poem, I discovered the possibilities of poetry. But it was film that got me there. I discovered Whitman through Bette Davis. Go figure. Simpson would say that my sentimental little story, touching as it may be, is irrelevant. So what if one or two converts to poetry are found? It’s nice that someone is listening, but that is secondary to the true purpose of poetry: greatness. I ask what good is greatness if it has no impact? Another interesting aspect of Simpson’s essay is his reverence for the great poets of the past and their secondary consideration of the public to their writing. He says that to Dante, Chaucer, Milton, Wordsworth, Whitman, Yeats, and Eliot, among many others, the act of writing reigned supreme over important matters such as politics, philosophy, and religion. The concern of public opinion was of secondary importance. But poets and their great works were read and discussed at a time when poetry made an impact—a time when poetry was a staple of the intellectual diet. They had the luxury of not being completely overshadowed by television, movies, rock and roll, and the computer revolution. While the audience for poetry still consisted mainly of a group of educated, intellectually interested individuals, poetry had not yet been reduced in its cultural importance, as it has been today; thus, it had a greater impact on the world around it. Great poets, such as Lord Byron and Walt Whitman, could be subjects of great and heated debate within the higher circles of society as well as being relatively well known to the general population. Those days are far behind us. Today, would they be great poets? Most assuredly so. Would they be famous? I doubt it. Would the “audience of general intellectual interest” be thrilled or 4 shocked by their poems? Highly doubtful. Today, we do not care. The phrases “created a literary sensation” and “turned the poetry world upside down” are almost comical in their innocuous implications for our culture. Poetry has become stuck in a world whose access by an interested audience is limited. Academia has created an isolated, specialized world of poetry where a “sub-culture” exists with an audience consisting primarily of poets and critics. Dana Giola aptly observes that however healthy this subculture may seem, it has lost the larger intellectual audience “who represent poetry’s bridge to the general culture.” This audience is essential if poetry is to rid itself of its elitist trappings and forge a new and meaningful relationship with our culture. Without it, poetry, no matter its greatness, will remain inconsequential to anybody other than the poet and the critic, “imprisoned in an intellectual ghetto.”4 A great poem, unread by those who could benefit most, will never reach its full potential. Does this matter? I think it does. If it did not, there would be no objection to poetry remaining exactly where it is and the issue of the neglect of poetry would be moot. Today, poetry lies in the shadow of other art forms in its cultural importance, unable to reach a society incapable of listening. It must break free and show its splendor to more than its creators, more than its critics. It must find a way to be heard again, for if it does not, it is doomed to remain locked away in the institutionalized confinement Louis Simpson abhors, tragically resplendent in its unheard beauty. Levitt Prize, 1999