athens - Hazlet.org

advertisement

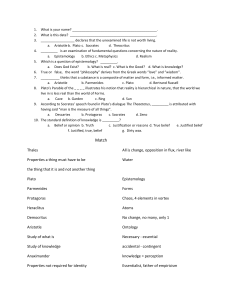

Athens Athens was a polis on the southeastern part of the Greek mainland. The Athenian people valued reading, writing, and music, subjects that the Spartans scorned. Unlike Sparta, the leaders of Athens allowed the people born in their polis to visit other places and learn new ideas. The people of Athens created a democracy: a government ruled by the people instead of a king. Every adult male born in Athens became a citizen and a member of the assembly. The assembly voted on how the polis was governed. To ensure equal opportunity for every citizen, Athens chose it’s leaders by lot rather than by holding elections. The elected officials served for one year. At the end of the year, the leaders were called before the assembly to account for their work. Not everyone participated in Athenian democracy. Athens encouraged outsiders to move to their polis, but did not allow them to vote. Women could own land, but could not actively participate in the assembly. The members of the assembly accounted for only about one-sixteenth of the total population of Athens. About one in four people were slaves. The slaves did most of the work in the polis, making it possible for the members of the assembly to spend more time on public affairs. Athenian democracy was limited, but it gave some people the opportunity to make decisions about how they were governed. Participation in government by common people was a new idea that later became a model for other governments. ATHENS The early city-state. In the mid-9th century BC, the surrounding territory, including the seaport of Piraeus, was incorporated into the city-state of Athens. When the monarchy was replaced by an aristocracy of nobles, the common people had few rights. The city was controlled by the Areopagus (Council of Elders), who appointed three (later nine) magistrates, or archons, who were responsible for the conduct of war, religion, and law. Discontent with this system led to an abortive attempt at tyranny (dictatorship) by Cylon (632 BC). Continued unrest led to Draco’s (fl. 650–621 BC) harsh but definite law code enacted in 621 BC. The code only compounded the social and economic crises, but eventually it brought about the consensus appointment of Solon as archon in 594 BC. Solon established a council (see boule), a popular assembly (ekklesía), and law courts. He also encouraged trade, reformed the coinage, and invited foreign businessmen to the city. His reforms, however, were only partially successful. The age of tyrants. Between 560 and 510 BC Athens was ruled under the tyrant Pisistratus and his sons Hippias and Hipparchus (c. 555–514 BC). Pisistratus enlarged the meeting place of Solon’s council in the agora (marketplace) and built a new temple of Athena, the city’s patron goddess, on the Acropolis. Pisistratus also sponsored public events such as the Panathenaic festival, held every fourth year in Athena’s honor. Many other public works were undertaken during this period. In 508 BC Cleisthenes led a democratic revolution, reorganizing the city’s tribal structure so that the base of his support was in the more democratic urban center and in Piraeus. The powerful popular assembly met on the Pnyx hill below the Acropolis. The classical period. In 480 BC Athens was sacked and nearly destroyed by the Persians (see Greece: Persian Wars). The Athenian leader Themistocles, having defeated the Persian invaders at Salamis, began the restoration of the city, building circuit walls around both Athens and Piraeus. He also began construction of walls connecting Athens with the port. His work was continued by Pericles in the 450s BC. Pericles, more than any other democratic leader, made Athens a great city. Public funds were used to build the Parthenon, the temple of Niké, the Erechtheum, and other great monuments. He developed the agora, which began to display imports from around the world. As head of the Delian League of Greek city-states, Athens was now an imperial power; its courts tried cases from all over the Aegean. The culture of the city was magnificent. Great tragedies and comedies were produced in the theater of Dionysus, below the Acropolis, and Pericles’ circle included leading intellectuals. The city, with its democratic constitution and brilliant way of life, became the “school of Hellas.” At its height, the population was perhaps 200,000 people, of whom 50,000 were full male citizens; the rest—women, foreigners, and slaves—were not citizens. After its defeat by Sparta in the destructive Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), the city began to decline. Socrates was forced to take his own life when he questioned traditional ideas, and an attitude of pessimism prevailed. Nevertheless, philosophy continued to flourish. In the 4th century BC Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum were founded as philosophical schools, and Demosthenes, Isocrates, and others made rhetoric a fine art. Sparta Sparta was a polis that valued physical courage, strength, and bravery in war. The Spartans gave their complete loyalty to the polis. Seven-year-old Spartan boys left their homes to train as soldiers in military camps. Spartan men lived and trained together. When a man married, he would continue to live with his fellow soldiers until he was about 30 years old. Both men and women in Sparta participated in athletic contests to make them strong. Spartan laws discouraged anything that would distract people from their disciplined military life. Sparta did not welcome visitors from other cities, and Spartans were not allowed to travel. The Spartans were not interested in other ways of life and did not want to bring new ideas to their polis. Sparta is on the Peloponnesus, a hilly, rocky area at the southern end of the Greek peninsula. The Spartans conquered many people in the region and forced them to work as slaves. They developed their disciplined society because they were outnumbered by slaves, and needed to always be prepared for a slave revolt. SPARTA Ancient Sparta. The ancient city, even in its most prosperous days, was merely a group of five villages with simple houses and a few public buildings. The passes leading into the valley of the Evrótas were easily defended, and Sparta had no walls until the end of the 4th century BC. The inhabitants of Laconia were divided into Helots (slaves), who performed all agricultural work; Perioeci, a subject class of free men without political rights, who were mainly tradesmen and merchants; and the Spartiatai, or governing class, rulers and soldiers, descended from the Dorians, who had invaded the area about 1100 BC. The foundation of Spartan greatness was attributed to the legislation of Lycurgus, but was more probably the result of ascetic reforms introduced about 600 BC. In the 7th century BC, life in Sparta was similar to that in other Greek cities, and art and poetry, particularly choral lyrics (see ALCMAN), flourished. From the 6th century BC on, however, the Spartans looked upon themselves as merely a military garrison, and all their discipline pointed to war. No deformed child was allowed to live; boys began military drill at the age of 7 and entered the ranks at 20. Although permitted to marry, they were compelled to live in barracks until the age of 30; from the ages of 20 to 60 all Spartans were obliged to serve as hoplites (foot soldiers) and to eat at the phiditia (“public mess”). The earliest struggles of Sparta were with Messinía, the southwestern district of Pelopónnisos, and Argos, a city located in northeastern Pelopónnisos. The Messenian War terminated about 668 BC in the complete overthrow of the Dorians of Messinía, most of whom were reduced to the status of helots. In the wars with the descendants of the original Achaeans and with the Dorians of Argos, the Spartans were generally successful. Under their stern discipline, the Spartans became a race of resolute, ascetic warriors, capable of self-sacrificing patriotism, as shown by the devoted 300 heroes at THERMOPYLAE (q.v.; see also LEONIDAS I), but utterly unable to adopt a wise political and economic program. The outbreak of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC finally brought the rivalry between Sparta and Athens to a head. Upon the overthrow of Athens in 404 BC, Sparta became the dominant Greek state, but the Thebans under Epaminondas in 371 BC deprived Sparta of its power and territorial acquisitions, reducing the state to its original boundaries. Sparta later became a portion of the Roman province of Achaea and seems to have prospered in the early centuries of the Roman Empire. The city itself was destroyed by the Goths under their king, Alaric I, in 396 AD. Socrates Socrates was a Greek philosopher who taught by asking questions. When teachers ask questions that encourage students to draw conclusions, they are using the "Socratic method" of teaching. The oracle of the prominent polis of Delphi pronounced Socrates the wisest man in Greece. Socrates concluded that while others professed knowledge they did not have, he knew how little he knew. Socrates asked many questions, but he gave few answers. He often denied knowing the answers to the questions he asked. Socrates was a well-known teacher in Athens. He drifted around the city with his students, engaging many people in arguments about "justice, bravery, and piety." What we know about Socrates comes from what others wrote about him. Socrates did not write any books because he believed in the superiority of argument over writing. Socrates' students wrote that he believed that evil is ignorance, and that virtue could be taught. According to this philosophy, all values are related to knowledge. Evil is ignorance, and virtue can be taught. Socrates regarded the tales of the gods as an invention of the poets. The leaders of Athens did not want a critic like Socrates in their city. They threatened to bring him to trial for neglecting the gods and for corrupting the youth of Athens by encouraging them to consider new ideas. The leaders expected the seventy-year-old Socrates to leave Athens before his arrest, but he remained in Athens, stood trial, and was found guilty. A friend tried to plan an escape from prison, but Socrates refused to participate. He believed that he must obey the law, even if his disagreed with it. His last day was spent with friends and admirers. At the end of the day, Socrates calmly drank from a cup of poison hemlock, the customary practice of execution at that time. SOCRATES (c. 470–399 BC), Greek philosopher, who profoundly affected Western philosophy through his influence on Plato. Born in Athens, the son of Sophroniscus, a sculptor, and of Phaenarete, a midwife, he received the regular elementary education in literature, music, and gymnastics. Later he familiarized himself with the rhetoric and dialectics of the Sophists, the speculations of the Ionian philosophers, and the general culture of Periclean Athens. Initially, Socrates followed the craft of his father; according to a former tradition, he executed a statue group of the three Graces, which stood at the entrance to the Acropolis until the 2d century AD. In the Peloponnesian War with Sparta he served as an infantryman with conspicuous bravery at the battles of Potidaea in 432–430 BC, Delium in 424 BC, and Amphipolis in 422 BC. Socrates believed in the superiority of argument over writing and therefore spent the greater part of his mature life in the marketplace and public resorts of Athens in dialogue and argument with anyone who would listen or who would submit to interrogation. Socrates was unattractive in appearance and short of stature but was also extremely hardy and self-controlled. He enjoyed life immensely and achieved social popularity because of his ready wit and a keen sense of humor that was completely devoid of satire or cynicism. Attitude Toward Politics. Socrates was obedient to the laws of Athens, but he generally held aloof from politics, restrained by what he believed to be divine warning. He considered that he had received a call to the pursuit of philosophy and could serve his country best by devoting himself to teaching and by persuading the Athenians to engage in self-examination and in tending to their souls. He wrote no books and established no regular school of philosophy. All that is known with certainty about his personality and his way of thinking is derived from the works of two of his distinguished scholars: Plato, who at times ascribed his own views to his master, and the historian Xenophon, a prosaic writer, who probably failed to understand many of Socrates’ doctrines. Plato represents Socrates as hiding behind an ironical profession of ignorance, known as Socratic irony, and possessing a mental acuity and resourcefulness that enabled him to penetrate arguments with great facility. Teachings. Socrates’ contribution to philosophy was essentially ethical in character. Belief in a purely objective understanding of such concepts as justice, love, and virtue, and the self-knowledge that he inculcated, were the basis of his teachings. He believed that all vice is the result of ignorance, and that no person is willingly bad; correspondingly, virtue is knowledge, and those who know the right will act rightly. His logic placed particular emphasis on rational argument and the quest for general definitions, as evidenced in the writings of his younger contemporary and pupil Plato and of Plato’s pupil Aristotle. Through the writings of these philosophers Socrates had a profound effect on the entire subsequent course of Western speculative thought. Another thinker befriended and influenced by Socrates was Antisthenes, the founder of the Cynic school of philosophy. Socrates was also the teacher of Aristippus, who founded the Cyrenaic philosophy of experience and pleasure, from which developed the more lofty philosophy of Epicurus. The ideal Socrates, depicted in Plato’s Apology, Crito, Gorgias, and Phaedo, became, as the influence of the ancient Greek and Roman divinities waned, the chief religious type of the ancient world. To such Stoics as the Greek philosopher Epictetus, the Roman philosopher Marcus (or Lucius) Annaeus Seneca the Elder (c. 55 BC–c. AD 39), and the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, he appeared as the very embodiment and guide of the higher life. The Trial. Although a patriot and a man of deep religious conviction, Socrates was nonetheless regarded with suspicion by many of his contemporaries, who disliked his attitude toward the Athenian state and the established religion. He was charged in 399 BC with neglecting the gods of the state and introducing new divinities, a reference to the daemonion, or mystical inner voice, to which Socrates often referred. He was also charged with corrupting the morals of the young, leading them away from the principles of democracy; and he was wrongly identified with the Sophists, possibly because he had been ridiculed by the comic poet Aristophanes in the Clouds as the master of a “thinking-shop” where young men were taught to make the worse reason appear the better reason. Plato’s Apology gives the substance of the defense made by Socrates at his trial; it was a bold vindication of his whole life. He was condemned to die, although the vote was carried by only a small majority. When, according to Athenian legal practice, Socrates made an ironic counterproposition to the court’s death sentence, proposing only to pay a small fine because of his value to the state as a man with a philosophic mission, the jury was so angered by this offer that it voted by an increased majority for the death penalty. Socrates’ friends planned his escape from prison, but he preferred to comply with the law and die for his cause. His last day was spent among his friends and admirers, and in the evening he calmly fulfilled his sentence by drinking a cup of hemlock according to a customary procedure of execution. Plato described the trial and death of Socrates in the Apology, the Crito, and the Phaedo. Plato Most of what we know about Socrates comes from Plato, his most famous student. Plato called Socrates “the best of all men I have ever known.” When his mentor was executed, Plato left Greece for more than a decade. He returned to start the Academy, a school that would operate for more than 900 years. Plato described his idea of an ideal society in his most famous book, the Republic. Plato did not believe in democracy. He argued in favor of an “aristocracy of merit,” rule by the best and the wisest people. Plato believed a small group of people intelligent and educated men and women should govern society. This small group would select the best and the brightest students to join them. Plato believed the government should rear all children so that everyone would have equal opportunities. Schools would test students on a regular basis. Those who did poorly would be sent to work, while those who did well would continue their studies. At the age of thirty-five, those persons who mastered their education would be sent to the workplace to apply their learning to the real world. After fifteen years, if the student succeeded, they would be admitted to the guardian class. Plato taught that the ideals of truth or justice cannot exist in the material world. Today we describe a "platonic" relationship as one in which people have mental and spiritual exchanges but refrain from physical intimacy. PLATO (c. 428–c. 347 BC), Greek philosopher, one of the most creative and influential thinkers in Western philosophy. Life. Plato was born to an aristocratic family in Athens. His father, Ariston, was believed to have descended from the early kings of Athens. Perictione, his mother, was distantly related to the 6thcentury BC lawmaker Solon. When Plato was a child, his father died, and his mother married Pyrilampes, who was an associate of the statesman Pericles. As a young man Plato had political ambitions, but he became disillusioned by the political leadership in Athens. He eventually became a disciple of Socrates, accepting his basic philosophy and dialectical style of debate: the pursuit of truth through questions, answers, and additional questions. Plato witnessed the death of Socrates at the hands of the Athenian democracy in 399 BC. Perhaps fearing for his own safety, he left Athens temporarily and traveled to Italy, Sicily, and Egypt. In 387 BC Plato founded the Academy in Athens, the institution often described as the first European university. It provided a comprehensive curriculum, including such subjects as astronomy, biology, mathematics, political theory, and philosophy. Aristotle was the Academy's most prominent student. Pursuing an opportunity to combine philosophy and practical politics, Plato went to Sicily in 367 BC to tutor the new ruler of Syracuse, Dionysius the Younger, in the art of philosophical rule. The experiment failed. Plato made another trip to Syracuse in 361 BC, but again his engagement in Sicilian affairs met with little success. The concluding years of his life were spent lecturing at the Academy and writing. He died at about the age of 80 in Athens in 348 or 347 BC. Influence. Plato's influence throughout the history of philosophy has been monumental. When he died, Speusippus (407?–339 BC) became head of the Academy. The school continued in existence until AD 529, when it was closed by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, who objected to its pagan teachings. Plato's impact on Jewish thought is apparent in the work of the 1st-century Alexandrian philosopher Philo Judaeus. NEOPLATONISM, (q.v.), founded by the 3d-century philosopher Plotinus, was an important later development of Platonism. The theologians Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and St. Augustine were early Christian exponents of a Platonic perspective. Platonic ideas have had a crucial role in the development of Christian theology and also in medieval Islamic thought (see ISLAM,). During the RENAISSANCE, (q.v.), the primary focus of Platonic influence was the Florentine Academy, founded in the 15th century near Florence. Under the leadership of Marsilio Ficino, members of the Academy studied Plato in the original Greek. In England, Platonism was revived in the 17th century by Ralph Cudworth and others who became known as the CAMBRIDGE PLATONISTS, (q.v.). Plato's influence has been extended into the 20th century by such thinkers as Alfred North Whitehead, who once paid him tribute by describing the history of philosophy as simply “a series of footnotes to Plato.” Aristotle Aristotle was the greatest scientist of the ancient world. He is considered the father of the natural sciences. Aristotle believed in using logic and reason, rather than the anger or pleasure of gods, to explain events. Aristotle was born in Macedonia, a mountainous land north of the Greek peninsula. At that time, many Greeks believed Macedonia was a backward place with no culture. Aristotle moved to Athens and studied at Plato’s Academy. He remained at the school for more than twenty years until shortly after Plato died. Aristotle then returned to Macedonia, where King Philip hired him to prepare his thirteen-year-old son, Alexander, for his future role as a military leader. His student would one day be known as known as Alexander the Great, one of the greatest military conquerors of all time. Once Alexander became King of Macedonia, Aristotle returned to Athens and opened a school he called the Lyceum. For the next twelve years, Aristotle organized his school as a center of research on astronomy, zoology, geography, geology, physics, anatomy, and many other fields. Aristotle wrote 170 books, 47 of which still exist more than two thousand years later. Aristotle was also a philosopher who wrote about ethics, psychology, economics, theology, politics, and rhetoric. Later inventions like the telescope and microscope would prove many of Aristotle’s theories to be incorrect, but his ideas formed the basis of modern science. ARISTOTLE (384–322 BC), Greek philosopher and scientist, who shares with Plato the distinction of being the most famous of ancient philosophers. Aristotle was born at Stagira, in Macedonia, the son of a physician to the royal court. At the age of 17, he went to Athens to study at Plato's Academy. He remained there for about 20 years, as a student and then as a teacher. When Plato died in 347 BC, Aristotle moved to Assos, a city in Asia Minor, where a friend of his, Hermias (d. 345 BC), was ruler. There he counseled Hermias and married his niece and adopted daughter, Pythias. After Hermias was captured and executed by the Persians, Aristotle went to Pella, the Macedonian capital, where he became the tutor of the king's young son Alexander, later known as Alexander the Great. In 335, when Alexander became king, Aristotle returned to Athens and established his own school, the Lyceum. Because much of the discussion in his school took place while teachers and students were walking about the Lyceum grounds, Aristotle's school came to be known as the Peripatetic (“walking” or “strolling”) school. Upon the death of Alexander in 323 BC, strong anti-Macedonian feeling developed in Athens, and Aristotle retired to a family estate in Euboea. He died there the following year. Works. Aristotle, like Plato, made regular use of the dialogue in his earliest years at the Academy, but lacking Plato's imaginative gifts, he probably never found the form congenial. Apart from a few fragments in the works of later writers, his dialogues have been wholly lost. Aristotle also wrote some short technical notes, such as a dictionary of philosophic terms and a summary of the doctrines of Pythagoras. Of these, only a few brief excerpts have survived. Still extant, however, are Aristotle's lecture notes for carefully outlined courses treating almost every branch of knowledge and art. The texts on which Aristotle's reputation rests are largely based on these lecture notes, which were collected and arranged by later editors. Among the texts are treatises on logic, called Organon (“instrument”), because they provide the means by which positive knowledge is to be attained. His works on natural science include Physics, which gives a vast amount of information on astronomy, meteorology, plants, and animals. His writings on the nature, scope, and properties of being, which Aristotle called First Philosophy (Protf philosophia), were given the title Metaphysics in the first published edition of his works (c. 60 BC), because in that edition they followed Physics. His treatment of the Prime Mover, or first cause, as pure intellect, perfect in unity, immutable, and, as he said, “the thought of thought,” is given in the Metaphysics. To his son Nicomachus he dedicated his work on ethics, called the Nicomachean Ethics. Other essential works include his Rhetoric, his Poetics (which survives in incomplete form), and his Politics (also incomplete). Influence. Aristotle's works were lost in the West after the decline of Rome. During the 9th century AD, Arab scholars introduced Aristotle, in Arabic translation, to the Islamic world. The 12th-century SpanishArab philosopher Averroës is the best known of the Arabic scholars who studied and commented on Aristotle. In the 13th century, the Latin West renewed its interest in Aristotle's work, and St. Thomas Aquinas found in it a philosophical foundation for Christian thought. Church officials at first questioned Aquinas's use of Aristotle; in the early stages of its rediscovery, Aristotle's philosophy was regarded with some suspicion, largely because his teachings were thought to lead to a materialistic view of the world. Nevertheless, the work of Aquinas was accepted, and the later philosophy of SCHOLASTICISM, (q.v.) continued the philosophical tradition based on Aquinas's adaptation of Aristotelian thought. The influence of Aristotle's philosophy has been pervasive; it has even helped to shape modern language and common sense. His doctrine of the Prime Mover as final cause played an important role in theology. Until the 20th century, logic meant Aristotle's logic. Until the Renaissance, and even later, astronomers and poets alike admired his concept of the universe. Zoology rested on Aristotle's work until Charles Darwin modified the doctrine of the changelessness of species in the 19th century. In the 20th century a new appreciation has developed of Aristotle's method and its relevance to education, literary criticism, the analysis of human action, and political analysis. Not only the discipline of zoology, but the world of learning as a whole, seems to amply justify Darwin's remark that the intellectual heroes of his own time “were mere schoolboys compared to old Aristotle.”