Monsters and Criminals:

advertisement

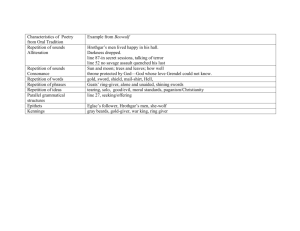

The Monster’s Mother at Yuletide Leo Tepper The purpose of this article is to investigate the theme of the monster’s mother, the fight against a monster or dragon and Yuletide.1 These three themes occur in various Germanic sources and are interrelated, as will be shown in this article. It will also be shown that these themes and their relationship have some very interesting parallels in Indo-Iranian mythology. and thus point to an Indo-European mythological motive. My point of departure is the Anglo-Saxon heroic poem Beowulf. In this poem the hero Beowulf sets out to fight with various monsters. The first monster he encounters is Grendel, who lives in a moor and every night ravages the hall of king Hroðgar (lines 710–836). The battle is fierce and bitter, Beowulf strikes off Grendel’s arm and the monster escapes mortally wounded to his dwelling-place. There is, however, more evil to come, this time from Grendel’s mother, who avenges her son. A greater part of the poem (lines 1251–1784) is devoted to the battle between Beowulf an Grendel’s mother , rather than to Beowulf ’s fight with Grendel. The last monster to be defeated is a dragon, but whereas Beowulf slays the first monsters in his youth, this last monster is killed when he is a man of old age, and he himself is mortally wounded in the process (lines 2200–3182).2 In this article I will pay special attention to the second fight, the battle with the monster’s mother and put it in a wider context. In the Beowulf the following description is given of Grendel’s mother: she is an ides āglæcwīf ‘a mighty woman among monsters’ (line 1259), and she and her son are ellorgæstas ‘alien spirits’ (Klaeber) or ‘creatures of the otherworld’ (Garmonsway) (line 1349). She lives with her son outside society in an inhospitable area (lines 1357-61): 1 This article has been made possible by a grant from the Dutch organisation for scientific and scholarly research (NWO). 2 I have used the translation by G. N. Garmonsway and Jacqueline Simpson, Beowulf and its Analogues, 2nd edn. (London: J.M. Dent and Sons, 1981), which also contains translations of the relevant Old Icelandic passages. For the text I have used Beowulf and the Fight at Finnsburg, ed. Fr. Klaeber, 3rd edn. with first and second supplements (1936; Boston, MA: D. C. Heath and Co., 1950). 1 Hīe dygel lond warigeað wulfgleoþu, windige næssas, frēcn fengelād, ðær fyrgenstrēam under næssa genipu niþer gewīteð flōd under foldan. ‘They (Grendel and his mother) have made their abode in a secret land of wolf-haunted slopes, windswept crags and perilous fen-paths, where a mountain torrent plunges downwards, hidden by the mists of the crags, and the flood plunges under the earth . Beowulf goes to her abode, together with king roðgar and a troop of men. He jumps into the water and dives to find the cavern of the mother. She waits for him and carries him with a firm grip to her dwelling-place (lines 1501-2): Grāp þā tōgēanes, gūðrinc gefēng atolan clommum. `She grasped him, she clutched the warrior in a terrible lock.’ Beowulf is then taken to her hall under water. To his surprise he sees a fire under water (lines 1512–17): Ðā se eorl ongeat, þæt hē [in] niðsele nāthwyclum wæs, þær him nænig wæter wihte ne sceþede, nē him for hrōfsele hrīnan ne mehte færgripe flōdes; fyrlēoht geseah, blācne lēoman beorhte scīnan `The hero then observed that he was inside some enemy hall, where no water could harm him, nor could the sudden tug of the flood reach him, because of this roofed chamber; he saw light of a fire, a glowing flame shining brightly.’ It is only with the greatest difficulty that Beowulf is able to defeat Grendel’s mother there. Ever since the mid-nineteenth century it has been recognized that the story of Beowulf and Grendel and his mother does not stand alone within Germanic literature. There are a number of parallels within the Old Icelandic sagas. The most important saga on which most studies have focused is the Grettis saga, from about the 2 end of the 13th century, but the theme of the monster’s mother also occurs in a number of other sages.3 I’ll start with a summary of the episode with the analogue with Beowulf covers chapters 64-66 of Grettis saga : A troll-woman harasses at Yuletide two consecutive years a farmstead, called Sandhaugar. Grettir hears this and offers to fight her. At the third Yuletide the troll-woman enters at midnight the farm, where Grettir is keeping vigil. They fight, but the trollwoman is very strong. At a certain moment the woman seizes him and drags him to the river, where she lives, and ‘Hon hafði haldit honum svá fast at sér, at hann mátti hvárigri hendi taka til nökkurs’ ‘She held him so tightly clasped that he could make no use of either arm’. Eventually Grettir is able to free himself, he draws his sword and hews off her right arm. She jumps into the river and disappears behind the waterfall. Some weeks later Grettir returns to the spot and with the help of the parish priest, who holds a rope, he climbs down to the river and dives to the bottom to get behind the waterfall, and sees there a cave. He sees a fire burning, and a giant who immediately springs up and attacks Grettir, but Grettir proves the stronger and kills the giant. The theme of a monstrous mother and son is also found in Orms Þáttr, a relatively late Icelandic work from c. 1300. In this short story a man called Ásbjörn goes to an island to fight a huge man-eating troll (chapters 6–9): En móðir hans var þó verri viðreignar en þat var kolsvört ketta ok svó mikil sem þau blótnaut at stærst verða.4 ‘His mother however, was even worse to deal with ― she was a coal-black she-cat, and as big as the sacred oxen, which are the biggest’. He fails and is killed, but next winter his friend Ormr goes to the island and with the help of God and the apostle Peter he defeats first the mother and thereafter her son. These few examples indicate the importance of the theme under discussion. The different accounts within the Old Icelandic tradition do not suggest a direct literary borrowing from each other; rather, they derive from a common Germanic tradition which has been treated differently by the various authors. 5 The relationship between Beowulf on the one hand and the sagas on the other hand has been hotly debated, but nowadays there is a general agreement that both derive their material from a common Germanic source.6 As Liberman puts it: ‘The “com3 All relevant passages are collected in Beowulf, trans. Garmonsway, pp. 301–31. 4 Anthony Faulkes, Two Icelandic Stories, Hreiðars Þáttr, Orms Þáttr, 2nd edn. (London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 1978), p. 72. 5 Cf. the discussion of the relationship between Grettis Saga and Orms Þáttr in Two Icelandic Stories, pp. 35– 36, 43–46. 6 See A. Liberman ‘Beowulf- Grettir’ in Germanic Dialects, Linguistic and Philological Investigations, eds. Bela 3 mon source”, that is, the ancient tale about a hero killing monsters, originally had nothing to do with Beowulf or Grettir, it was used in the Old English heroic poem and later in an Icelandic saga, because both Beowulf and Grettir were expurgators, and the plot fitted their characters’.7 . Let us look at the theme in some detail. The various element are: 1) A monster is living with his mother 2) They live outside human society (see the haunting description in Beowulf) 3) They live near or under water There are also a few differences: In the Beowulf the giamt is killed first and afterwards his mother, whereas in the extant saga-tradition the woman is killed first. The saga’s are also specific on the date, namely Yuletide. Furthermore the relationship between the troll woman and the giant in Grettis saga is not clear. But the elements listed above can be regarded as belonging to the original version. At the beginning of this century the Danish Iranist and buddhologist Edvard Lehmann published an article in which he investigated the theme of ‘the mother of the monster’.8 A distant echo of this theme is still found, according to Lehmann, in expressions in which the Devil and his mother or grandmother occur. These expressions are found all over the Germanic speaking area and Lehmann has collected a number of these, as for example: ‘Es ist eben Vieh als Stall, sagte der Teufel, er jagte seiner Mutter Fliegen in den Hintern’ (quoted from Luther). ‘Der Teufel und seine Grossmutter sind zu Gaste im Haus’ (said when there is trouble). These sayings express an antagonism between the Devil and his mother or grandmother., but in Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors (IV,3) it is said: ‘It is the devil’ - ‘Nay, she is worse, she is the devil’s dam’. Lehmann also notes other sayings in which there is no antagonism between the Devil and his consort but a co-operation: ‘The devil and his dam are verily let loose on us.’ Brogyanyi & Thomas Krömmelbein (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1986), pp. 353–401 for an overview and analysis of the various theories concerning the relationship between Beowulf and Grettis saga. 7 Idem, p. 390. 8 Edvard Lehmann, ‘Teufels Grossmutter’, Archiv für Religionswissenschaft 8 (1905), 411–30. 4 After investigating a number of European fairytales and stories ( including Beowulf and Grettis saga) Lehmann draws the conclusion that the theme of mother and son is very specific in mythology.9 As an Iranist, Lehmann then draws attention to Iranian material and points to the existence of a female demon Druj, who accompanies Ahriman, the evil spirit in Iranian religion. This female demon is sometimes known as Geh, the demon of female impurity. This theme is regarded by Lehmann as a reflection of the theme of the Devil and his mother. As a further substantiation of his hypothesis he also points to Hades and Persephone, since they too are a couple living outside society in the underworld. It is at this point that Lehmann takes the wrong direction: Ahriman and Druj are not described as mother and son, neither are Hades and Persephone. Besides, as Persephone was abducted by Hades, she cannot pssubly be described as a monster, and one may wonder whether Grendel ans his mother were as sensitive to the music of Orpheus as Hades and Persephone were. There are, however, more striking parallels within Indo-Iranian mythology, which suit the theme far better and which also allow us to explain the various versions as developments of an IndoEuropean mythological theme. When we turn our attention to the Rigveda, we find Indra as one of the most important gods there, even the most important one when we consider the number of hymns addressed to him: about a quarter of the 1028 hymns of the Rigveda is devoted to this god. Indra is the most heroic god and must have embolished the ideal warrior in Vedic society. He is foremost a dragonslayer, especially the slayer of the dragon Vrtra. Time and again this deed is mentioned in the Rigveda and Vrtrahan ‘killer of Vrtra’ as Indra’s epitheton ornans. Indra is further known for his drinking of soma, the hallucinating draught which invigorates him. His weapon is the vajra, a hurling weapon which in later Indian tradition became identified as the thunderbolt.10 In spite of the importance of Indra’s battle against Vrtra and the countless references to this, detailed descriptions of it are sparse. One of these descriptions can be found in RV.I.32:11 9 Idem, p. 425. A number of expressions concerning the Devil and his mother or grandmother have already been collected by Jacob Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, 4th edn. (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann, 1876), pp. 841– 43, but Grimm was apparently unaware of the Grettis Saga. 10 No monograph has yet appeared on Indra which deals with all his aspects, but on Indra in general, see Herman Lommel, Der Arische Kriegsgott (Frankfurt a/M.: Vittorio Klostermann, 1939), who tends to overlook the fertility and ritual aspects of Indra, and Jan Gonda, Die Religionen Indiens, 2nd edn. (Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1978), pp. 53–62. On his relation with other deities, as far as he appears as a dual deity, see H. P. Schmidt, Bhaspati und Indra (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1968), and Gonda, The Dual Deities in the Religion of the Veda (Amsterdam: N.V. North-Holland Publishing Company, 1974), pp. 229–248. The striking parallels between Indra and Thor have long been recognized, as, for example, by Hermann Oldenberg, Die Religion des Veda, 3rd edn. (Stuttgart und Berlin: J. G. Gotta’sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger, 1917), p. 139. 11 The translation is that of W. D. O’Flaherty, The Rig Veda (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981), pp. 148–51, 5 1. Let me now sing the heroic deeds of Indra, the first that the vajra-wielder performed. He killed the dragon and pierced an opening for the waters; he split open the bellies of the mountains. 2. He killed the dragon who lay upon the mountain. Tvastr fashioned the roaring vajra for him.12 Like lowing cows, the flowing waters rushed straight down to the sea. 3. Wildly excited like a bull, he took the Soma for himself and drank the extract on the tríkadruka ceremony. Indra the Generous seized his vajra to hurl it as a weapon; he killed the firstborn of dragons. 4. Indra, when you killed the firstborn of dragons and overcame by your māyā the māyā of the māyā-possessors, at that very moment you brought forth the sun, the sky and dawn.13 Since then you have found no enemy to conquer you. 5. With his great weapon, the vajra, Indra killed the shoulderless Vrtra, his greatest enemy. Like the trunk of a tree whose branches have been lopped off by an axe, the dragon lies flat upon the ground. 6. For, muddled by drunkenness like one who is no soldier, Vrtra challenged the great hero who had overcome the mighty and who drank soma to the dregs. Unable to withstand the onslaught of his weapons, he found Indra an enemy to conquer him and was shattered, his nose crushed. 7. Without feet or hands he fought against Indra, who struck him on the nape of the neck with his vajra. The steer who wished to become the equal of the bull bursting with seed, Vrtra lay broken in many places. 8. Over him as he lay there like a broken reed the swelling water flow for Manu. Those waters that Vrtra had enclosed with his power ― the dragon now lay at their feet. 9. The vital energy of Vrtra’s mother ebbed away, for Indra had hurled his deadly weapon against her. Above was the mother, below was the son; Dānu lay down like a cow with her calf. 10. In the midst of the channels of the waters which never stood still or rested, the body was hidden. The waters flow over Vrtra’s secret place; he who found Indra an enemy to conquer him sank into long darkness. with slight alterations. 12 Tvastr is a creator god and the father of Indra, according to most Vedic sources, though sometimes this role is assigned to Dyaus. 13 In Vedic times the term māyā did not have the specific connotation of ‘illusion’. According to Gonda, Change and Continuity in Indian Religion (The Hague: Mouton & Co., 1965), p. 166, māyā in Vedic context had the meaning ‘incomprehensible wisdom and power enabling its possessor, or being able itself, to create, devise, contrive, effect, or do something’. 6 11. The waters who had the Dāsa for their husband, the dragon for their protector, were imprisoned like cows imprisoned by the Panis. When he killed Vrtra he split open the outlet of the waters that had been closed. 12. Indra, you became the hair of a horse’s tail when Vrtra struck you on the corner of the mouth. You, the one god, the brave one, you won the cows; you won the Soma; you released the seven streams so that they could flow. 13. No use was the lightning and thunder, fog and hail that he (Vrtra) had scattered about, when the dragon and Indra fought. Indra the Generous remained victorious for all time to come. 14. What avenger of the dragon did you see, Indra that fear entered your heart when you had killed him? Then you crossed the ninety-nine streams like the frightened eagle crossing the realms of earth and air. 15. Indra, who wields the vajra in his hand, is the king of that which moves and that which rests, of the tame and of the horned. He rules the people as their king, encircling all this as a rim encircles spokes. Since the appearance in 1942 of W. N. Brown’s article on the creation myth in the Rigveda, this hymn has generally been considered a creation myth.14 By killing the dragon Vrtra, Indra has released the waters, and sun, sky and dawn came into existence. It is not so much the creation of the earth, which was somehow pre-existent, but the releasing of those elements which make the earth habitable for human beings. As our subject is not this hymn itself, this is not the place for a detailed interpretation. Important is the sudden mentioning of the mother of Vrtra. In the Rigveda she is mentioned twice, here and at RV.III.30.8: You, much invoked Indra, have smashed the handless Kunāru, living together with Dānu. You have beaten up with your club the expanding, hostile, feetless Vrtra. The meaning of the word Kunāru is unclear, but it certainly refers to Vrtra, as the second part of this stanza makes clear. From these two references we can infer that Vrtra lived together with his mother and that he was killed first. The name of the mother, Dānu, means ‘fluid, drop, dew’.15 This name appears once in the plural (RV.X.120.6), where it means ‘demons’,16 but there it is probably a 14 W. N. Brown, ‘The creation myth of the Rig Veda’, JAOS 62 (1942), 85–98. His article was the first to be published which points the nature of Indra’s battle with Vrtra, but other authors independently reached the same conclusion: Heinrich Lüders, Varuna I: Varuna und die Wasser (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, 1951), pp. 183–96, whose work appeared in print later than Brown’s article because it was published posthumously; the part on Indra and Vrtra had already been finished in the mid-thirties); F. B. J. Kuiper, Ancient Indian Cosmogony (New Delhi: Vikas, 1983) contains a number of articles on this subject, the first published in 1949. 15 Manfred Mayrhofer, Kurzgefasstes Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindischen, 4 vols. (Heidelberg: Carl Winter 7 transfer from the name Dānu. Little attention has so far been paid to her, though in 1980 Miriam Robbins has tried to connect her with Indo-European goddesses.17 Still, this theme is not simply a whim of a Vedic poet but must also have been known in Iranian mythology.18 It does not occur in the Avesta but in a late Armenian chronicle. The reform of the Iranian religion and its theological reformulation by Zarathustra has led to the disappearance of much of pre-Zarathustrian mythology. A few mythical themes have survived in Armenian sources, as Armenia was for a long time under Iranian influence. An Armenian parallel occurs in Moses Khorenats’i’s fifth-century History of the Armenians, where a dragonslayer Tigrun is mentioned, who kills the dragon Azdahak, and leads Anoysh, the mother of dragons into captivity (chapter I.31).19 That this story is of Iranian origin is clear from the name of the dragon Azdahak, which is the same as Azi Dahaka, the dragon which occurs in the Avesta. 1956–80), II (1963), p. 33. But cf. Mayrhofer, Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindoarischen (Heidelberg, Carl Winter 1992), p. 719: ‘rigved. Wort, das an mehreren Stellen den Regen bezeichnet und von mehreren Interpreted als “träufelnd, träufelnde Flüssigkeit”, von anderen aber als “Gabe” (Regen ~ Himmelsgabe) aufgefasst wirt’. The last meaning is improbable for a demon. It is possible that we have two homonyms dānu, one connected with the root dā, and one connected with young Avestan dānu, f. ‘river’ and various European names of rivers (Don, Dānuvius, cf. Mayrhofer, EWA, p. 720). 16 K. F. Geldner, Rig-Veda , 4 vols.(Cambrindge, MA: Harvard University Press,1951-57), III, p. 346. 17 Miriam Robbins, ‘The Assimilation of Pre-Indo-European Goddesses into Indo-European Society’, JIES 8 (1980), 19–29. According to her, Dānu, the various names of rivers with the element *dānu/dōnu, the Greek Δάαος (male!), and the Irish Danu, all reflect a pre-Indo-European or proto-Indo-European goddess (20–21). Her reasoning, however, is circular: ‘A pre-IE or proto-IE stream *don-u- or *dan-u may have become personified as the goddess Dānu, mother of the arch-withholder of the waters Vrtra.’ (20) and ‘Further, several bear her name to this day’ (21). Which was first: the river from which a goddess was abstracted or the goddess who gave her name to rivers? In fact, Dānu in Vedic mythology is never considered a goddess. Robbins also misunderstands dānunas patī mitras toyor varuno in RV, I.136.3, which, she argues, implies that she was called ‘consort of Mitra and Varuņa’. Pada c/d sounds jyotismat ksatram āsāte ādityā dānunas patī / mitras tayor varuno yātayajjano ‘ryamā yātayajjana, ‘They have attained luminous dominion, both Aditya’s, lords of dānu. Under them Mitra is, Varuna is bringing men together, Aryaman is bringing men together.’ The word dānu is translated by Geldner as ‘(Himmels)gabe’ and explained as ‘rain’ (danu can both be derived from dā ‘to give’ and from an I.E. word for ‘flood, water’; see Mayrhofer, EWA I, pp. 719–20). It is of course formally possible to take dānunas as Dānu, the mother of Vrtra, but nothing in Indian mythology makes this likely. The expression dānunas patī also occurs at RV II.42.6, where it also refers to Mitra and Varuna, and at VIII.8.16, where the Aśvins are meant. It has nothing to do with a hierogamy, as Robbins suggests. 18 J. M. Stitt, Beowulf and the Bear’s Son: Epic, Saga, and Fairytale in Northern Germanic Tradition (New York and London: Garland, 1992) gives a number of parallels for various themes in Beowulf; he also refers to Indian and Iranian material. 19 R. W. Thomson, Moses Khorenats’i, History of the Armenians (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978), pp. 122–23. The date of Moses Khorenats’i is uncertain, but he is traditionally placed in the fifth 8 One might argue that the appearance of the monster’s mother in both IndoIranian mythology and Old-Germanic lore is merely coincidental; after all Grendel is a troll-like figure and no dragon. However, not only are dragons and monsters interchangeable at a symbolic level, but when we look closer at the Beowulf/Grettis Saga episode, on the one hand, and the defeat of Vrtra, on the other, further parallels emerge. First, there is the location: Grendel and his mother live in a haunting place outside society; one might call it a ‘non-world’. The same is true for Vrtra, the more so as the world is not yet created. It is through Vrtra’s defeat that the world is created; at that point the waters begin to flow and the sun begins to shine. This brings us to another parallel: the connection with water. We have seen that the very name Dānu refers to water and this parallels the abode of the monsters in Beowulf and Grettis Saga. Another possible parallel is the presence of the sun in both works. Beowulf sees the light of a fire in the cave ( line 1518): ‘He saw the light of a fire, a glowing flame shining brightly’. This detail, which also occurs in Grettis Saga (see above), could be trivial, but on the basis of the other analogues with the Vedic version it is at least not impossible that the fire in the Germanic tradition is a survival of the original theme of the captivity of the sun. One more parallel between the Germanic and Vedic material which is not immediately apparent should be mentioned: the location in time of the episodes. The Sandhaugar episode in takes place at Yuletide, a period especially known for the appearance of monsters and uncanny beings in Germanic tradition.20 In fact, Grettir is not the only Norse hero who defeats a monster at Yuletide. In chapter 23 of the saga of Hrolfr Kraki, the hero Bödvar also kills a dragon at this time of the year. The connection between between midwinter and the killing of dragons or monsters is also present in the Vedic myth of the dragonslayer even though some philological and historical detectivework is necessary to illustrate this presence. I have stated earlier that the Vedic myth of the dragonslayer is a creation myth. No time sphere is given in this myth, but since it is stated that the sun, sky and dawn were brought forth, we can safely say that it was at the beginning of time. Although this conclusion by itself is of little use, the following statement from the Indian ritual book Aitareya Āranyaka (c 700 BC) provides us with an important clue: ‘Indra having slain Vrtra became great, then century (idem, 2–8). In the version of Moses Khorenats’i the myth is transposed and Azhdahak is considered a contemporary of Cyrus. Tigrun is described as the most valiant of all Armenian kings and is a historical figure. n the reform of Zarathustra, see Mary Boyce, A History of Zoroastrianism, vol. 1 (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1975), pp. 193–246. 20 Jan de Vries, Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte, 2nd edn. 2 vols. (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 19562), I, p. 449. 9 there came into being the mahāvrata’.21 The mahāvrata is the Vedic wintersolstice festival dedicated to Indra as god of fertility.22 Already in the brāhmanas this festival is considered as antiquated and unproper for its overt sexual practices and many brāhmanas prescribe a censured version of it. Almost immediately preceding this festival is the ekāstakā, the night at which Indra is born. We can therefore conclude that the fight against Vrtra just preceded the wintersolstice. This is by no means surprising, as at that time the days start to become longer. We must bear in mind that in many cultures, including our own, time is circular rather than linear, and that at certain days of the year important happenings including the creation of the world are remembered or reenacted. When we return to the Germanic sources, we see that the coherent structure between the killing of the dragon and his mother, the release of waters and sun and the ritual setting of the wintersolstice has been disjoined in Germanic literature. Still, all the elements are discernable, and it has to be asked whether the arising parallels are coincidental. I do not think so, since they are in their configuration too specific to be independent of each other. Both the Indo-Iranian and the Germanic tales must derive from a common Indo-European myth, which is best preserved in the Rigveda. As a consequence, the Germanic monsters can be traced back to a time well beyond the genesis of Germanic literature, yet their origin makes them not mere relicts of an ancient past. Monsters, like every animal, adapt to new situations, and the difference between the monsters in the Veda and Germanic literature points to their vitality and ability to survive in new social and literary surroundings.23 21 Translation by A. B. Keith, The Aitareya Āranyaka (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1909), p. 161. This Āranyaka is attached to the Aitareya Brāhmana. It is divided into five books. The oldest parts of the first three can be dated around 700 BC and the last two about 550 BC; idem, 25–26. For the Āranyakas in general, see Gonda, Vedic Literature (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1975), pp. 423–33. 22 A. Hillebrandt, ‘Die Sonnwendfeste in Alt-Indien’, Romanische Forschungen 5 (1890), 299–340; Walter Friedlaender, Der Mahāvrata-Abschnitt des Śānkhāyana-Āranyaka (Berlin: Meyer & Mueller, 1900); A. B. Keith, The Śānkhāyana-Āranyaka with an Appendix on the Mahāvrata (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1908); Keith, Aitareya Āranyaka, pp. 26-39; J. W. Hauer, Der Vrātya, Untersuchungen über der nichtbrahmanische Religion Altindiens (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1927) , pp. 246–96; Pierre Rolland, Le Mahāvrata, Contribution à l’étude d’un rituel solemnel védique (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, 1972). Brahmanical descriptions of this festival can also be found in Taittiriya Samhitā VII.5.8–10; Pañcavimśa Brāhmana IV.10–V.6; Śānkhāyana Śrautasūtra XVII–XVIII. Klaus Mylius, Wörterbuch des Altindischen Rituals (Wichtrach: Institut für Indologie, 1995), p. 106, gives a complete list. 23 For an alternative explanation of the origin of expressions concerning the Devil and his mother/grandmother, see F. J. Dölger, Antike und Christentum, 6 vols. (Münster: Aschendorff, 1929–50), I (1932), pp. 153–76, derives this expression from early Christian usage to equate pagan gods with demons and devils. Cybele as Magna Mater was in certain cults the head of the gods and so became the Devil’s mother. Though it is not impossible that in certain areas this development has taken place, it does not 10 explain the similarities between the Germanic and Vedic sources. Moreover, it is difficult to see how this equation occurring in the writings of the Church Fathers could have influenced the mainly illiterate population of the early Germanic kingdoms. 11