Jonathan Swift Links

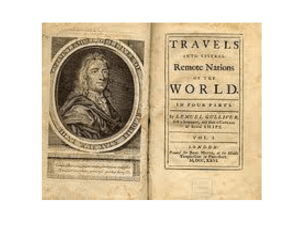

advertisement