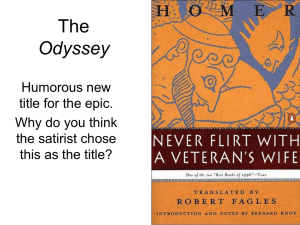

Personal Odyssey Project The Odyssey has withstood the test of

advertisement

Personal Odyssey Project The Odyssey has withstood the test of time, entertaining people around the world for hundreds of years, because it is a story whose themes are universal. For this project, you will analyze the themes of the Odyssey and relate them to your own life. Before you begin, please complete a Theme Analysis as your pre-writing stage. For this, simply list several possible themes and briefly explain each one. Then, begin making connections. Perhaps you will notice how heroic you truly are! Part One: Personal Odyssey Map Poster size map of your experiences Any medium is appropriate (drawn, painted, photographs, etc.) Minimum of five (5) “adventures” must be included Each “adventure” needs a symbol/pictorial representation of some kind; it may be a photo or clip art or it may be drawn; however, be consistent so that the pattern you have created is an obvious one Adventures must be connected in some logical fashion (arrows, a line, footprints, etc.) Neatness counts! Part Two: Personal Odyssey Report Detailed essay that presents, discusses, and analyzes each of your life adventures Length will vary; however, you must include a minimum of five (5) adventures Each adventure will be one or two paragraphs in length and will be the basis for the five book minimum you are creating Each adventure should receive a separate heading: Be Creative! Formal essay organization must be followed: MLA heading, title, typed-using 12 point font size The title of your essay will be: The Odyssey of ____________ (your name) Each adventure must include the following: the people involved, a description or explanation of the situation, how you were helped or hindered, and what heroic trait you used or learned about through the experience Each adventure will be connected with a reference to the amount of time that had passed since the previous adventure. For example: Five years after my uneventful birth, I encountered my first real challenge: going to kindergarten ALONE! For this report only, you may select a creative font style, but PLEASE be sure it is legible and easy to read…if in doubt, provide a sample first and obtain teacher approval! Part Three: Speech Turn the information gathered above into a speech about your own Odyssey! A rubric and lesson on speeches will follow. GRADING CRITERIA: Poster---- 25 points Neatness; effectively utilizing a full-sized sheet of poster board Creativity (choice of connectors and adventures) Inclusion of 5 Adventures (minimum) Typed Report---- 25 points MLA format; following directions (reread specifics mentioned above); error free Varied sentence structure; selection of transitional words and phrases Vocabulary choice (please make a conscious effort to use strong verbs, descriptive adjectives and a higher level of vocabulary without it sounding as if someone else wrote it!) Speech—TBD points Content + Correct Speech Demeanor…more info to follow! Personal Odyssey Rubric Name: _______________________ _________________________ Stock epithet? Y / N I. Posterboard II. Written Report A. Neatness (5) ________ B. Creativity/choice (5) ______ C. Five Adventures (15) ______ **** 3 points each A. Following directions (5) ________ B. Adventures (20) ________ **** inclusion of a heroic trait **** description of event **** identifying people involved **** helped or hindered??? TOTAL (25) TOTAL (25) _______ ____________ Final tally: _________ / 50 points Hospitality First shown to Telemachus by Nestor, then Menelaus. Shown to Odysseus by Alcinous and Arête. Contrasted with: The suitors The Cyclops (Book 9) The Laestrygonians (Book 10) Circe (Book 10) It is interesting that, although strangers are "protected" by Zeus, Zeus agrees with Poseidon that the Phaeacians are too hospitable to Odysseus. This seems a value more human than Olympian. Respect for the Gods Respect for the gods is shown through the numerous descriptions of sacrifices and offerings. Before feasting, the ritual involves "cutting the first strips for the gods" having them "wrapped in sleek fat . . . sprinkling barley over them" then "burning the choice parts for the gods that never die." Libations are also poured. Disrespect for the Gods inevitably leads to disaster; the Gods do not forget disrespect and are not easily appeased. (Poseidon, Athena, Aeolus, Helios.) Note how often Odysseus prays, especially after he makes the mistake with Polyphemus. The Importance of Lineage Almost every time we met someone significant the narration pauses and we learn of the lineage. Note how frequently a god is part of that lineage includes a god. (And how often the god is Zeus. Many "things" we see also have a lineage or history that we are given - note Odysseus scar and his bow. Loyalty Penelope's loyalty to Odysseus Athena's loyalty to her "Odysseus" and vice versa Loyalty between parents and offspring. The loyalty of Eurycleia The loyalty of Argos The loyalty of the Achaeans to each other. Pride and Honor Odysseus is guilty of excessive pride when he gives his name to Polyphemus (Book 9). Laodamus shows excess pride when he challenges Odysseus in Book 8. The suitors seem dangerously proud, especially when Odysseus returns. In the end, the suitors have dishonored Odysseus and must pay for this. On the other hand, a certain amount of pride and sense of honor is important. Note how Odysseus responds to the challenge of Laodamus. Telemachus needs to need to gain more pride so that he can stand up to the suitors who have dishonored his house. Resisting Temptation Generally, Odysseus resists temptation. But he does boast to Polyphemus, and he does seem reluctant to leave Circe's island. His men are tempted by the Lotus Eaters as well as Circe; and by greed several times - causing them to stay too long at the land of the Cicones, to open Aeolus' gift, and finally to eat the cattle of the sun (though in some ways this is more out of desperation than anything else). The suitors clearly cannot resist temptation. Live Life to the Fullest A major characteristic of Odysseus. He cannot resist the opportunity to "explore." He stays out of trouble by not being reckless. The episode with the Sirens is an example of both his exploration of life and of his precaution. He seems to understand how important to make the most of any moment, taking Achilles' description of death to heart. Self-discipline Foolishness and the lack of self-discipline lead to the loss of men with the Cicones and the loss of the crew on the Island of Helios. Odysseus loses his self-discipline with the Cyclops, but demonstrates it almost everywhere else, often in contrast with his crew. The Importance of Leadership This is a top down society. The leaders we meet (Odysseus, Nestor, Alcinous etc.) do not rule democratically. The rule by "divine right" and by force of character. Probably the most important quality of leadership is courage. Justice Odysseus, like Orestes, will eventually be a deliverer of justice. Justice takes time. Neither Orestes nor Odysseus can act immediately. When they do act justice is not tempered by mercy. Helen seems to be beyond justice. Justice can seem brutal - especially when it is meted out by Zeus or Poseidon directly - the Phaeacians are brutally punished for their assistance to Odysseus. Odysseus justice for the maids who slept with the suitors is also brutal. Revenge Homer seems to think that revenge is well justified and people are entitled to it. Reconciliation At the end of the book Athena ensures that the people of Ithaca are reconciled with Odysseus. The test Odysseus and various members of his family undergo with each other suggest that their reunions also involve reconciliation. Fate Fate is preordained by a power beyond that of even the gods. Paradoxically, it does not seem "random." A character's fate is tied up with his "character." Odysseus is fated to return home but he could not fulfill his fate if he were not who he is. then and there unlucky Odysseus would have met his death against the will of fate but the bright eyed one inspired him yet again. Fighting out from the breakers, pounding toward the coast, out of danger he swam on, scanning the land. . . (Book 5) Major Themes Home, wandering, and fidelity The title of The Odyssey has given us a word to describe a journey of epic proportions. Throughout his travels, Odysseus' central emotion is loneliness. We first encounter him as he pines away for home, alone on Kalypso's beach, and he is not above weeping when thinking of home at other points. He also endures great loss through the deaths of his brothers-in-arms from the Trojan War and his shipmates afterward. Loneliness pervades the emotions of other characters; Penelope is nearly in constant tears over her absent husband, Telemakhos has never known his legendary father, and Odysseus' mother explains that loneliness caused her death. Yet tempering Odysseus' desire to return home is the temptation to enjoy the luxurious surroundings he sometimes finds himself in‹particularly when he is in the company of beautiful goddesses. He happily spends a year on Kirke's island as her lover and does not seem to complain too much about his eight years of imprisonment on Kalypso's island. In both cases, Odysseus expresses little remorse about being unfaithful to his wife‹although infidelity is what he fears Penelope may be succumbing to at home. That Homer never reproaches Odysseus for his extracurricular romances but condemns the unfaithful women in the poem recalls Kalypso's angry statement about the double standard for immortals: male gods are allowed to take mortal lovers, while female goddesses are not. Likewise, men such as Odysseus have some freedom to "wander" sexually during their geographical wanderings‹so long as they are ultimately faithful to their home‹while Penelope and the other women in The Odyssey are chastised for their lack of chastity. Indeed, Odysseus does remain true to Penelope in his heart, and his desire to reunite with her drives his faithful journey. Fidelity is also central at the end of the poem, when Odysseus tests the loyalties of his servants and punishes those who have betrayed him. Cunning and disguise Odysseus' most prominent characteristic is his cunning; Homer's Greek audience generally admired the trait but occasionally disdained it for its dishonest connotations. Odysseus' skill at improvising false stories or devising plans is nearly incomparable in Western literature. His Trojan horse scheme (recounted here) and his multiple tricks against Polyphemos are shining examples of his ingenuity, especially when getting out of jams. Both examples indirectly relate to another dominant motif in The Odyssey: disguise. (The soldiers "disguise" themselves in the body of the Trojan horse, while Odysseus and his men "disguise" themselves as rams to escape from Polyphemos.) Odysseus spends the last third of the poem disguised as a beggar, both to escape from harm until he can overthrow the suitors and to test others for loyalty. In addition, Athena appears frequently throughout the poem, often as the character Mentor, to provide aid to Odysseus or Telemakhos. Women as predatory It is little wonder Odysseus fears Penelope's lapse into infidelity‹women are usually depicted, if anything, as sexual aggressors in The Odyssey. Kirke exemplifies this characteristic among the goddesses, turning the foolish men she so easily seduces into the pigs she believes them to be, while Kalypso imprisons Odysseus as her virtual sex-slave. The Seirenes, too, try to destroy passing sailors with their beautiful voices. The suitors even accuse Penelope of teasing them, a debatable point. But no woman receives as negative a portrait as Agamemnon's wife Kyltaimnestra; the story of her cuckoldry and murder of her husband frequently recurs as a parallel to Odysseus' anxieties about Penelope. Odysseus' character flaws Though he is usually a smart, decisive leader, Odysseus is prone to errors, and his deepest flaw is falling prey to temptation. His biggest mistakes come in the episode with Polyphemos as he first foolishly investigates the Kyklops' lair (and ends up getting trapped there), and then cannot resist shouting his name to Polyphemos after escaping (thus incurring Poseidon's wrath). If Odysseus' character changes over the course of The Odyssey, though, it pivots around temptation. After his errors with Polyphemos, Odysseus has his crew tie him up so he can hear‹but not follow‹the dangerously seductive song of the Seirenes. Disguised as a beggar in Ithaka, he is even more active in resisting temptation, allowing the suitors to abuse him as he bides his time. Temptation hurts his crew, as well, in their encounters with Kirke, the bag of winds from Aiolos, and the oxen of Helios. The power of the gods The gods exercise absolute power over mortal actions in The Odyssey. To curry the gods' favor, mortals are constantly making sacrifices to them. Conversely, offending the gods creates immense problems, as demonstrated by the oxen of Helios episode and Poseidon's grudge against Odysseus for blinding his son Polyphemos. Athena is the most visible god in the poem; only under her aegis can Odysseus survive his dangerous adventures, and she lobbies Zeus for his freedom and safety at other points. Her favoritism for him seems justified as a reward for his sacrifices and nobility of character; her distaste for the suitors is similarly understandable. The power of the gods, who usually care more about their internal disputes than about mortal behavior, is cemented at the end of the poem as Zeus orders a cease-fire between Odysseus and the suitors. Ultimately, the gods decide what happens in the mortal world; lack of free will receives more depth in The Iliad, but is a prominent theme in nearly any ancient Greek text, particularly ones that concern themselves with the omnipotent gods. Hospitality The Odyssey nearly serves as a Greek guide to hospitality, or "xenia," which was such a dominant concept in Greece that Zeus was the god of hospitality. Telemakhos and Odysseus receive warm hospitality throughout their journeys from others, usually without even having to give their names. The flip side of the equation, of course, is the suitors, who abuse Telemakhos' hospitality in running through Odysseus' reserves. The other blight on hospitality comes at the end when the Phaiakians, after Poseidon turns into stone their ship that carried Odysseus to Ithaka, decide not to give strangers conveyance anymore. Telemakhos' miniature odyssey: Paralleling Odysseus' greater journey, Telemakhos' journey at the beginning of the poem is as much a search for maturity as it is one for his father. Athena, who sparks his travels, also grooms him in the ways of a prince. Telemakhos matures from his initial weakness in the face of the suitors into the authoritative man of the house, and his place by his father's side in the climactic battle is well earned and represented.