20120419104828_440870606833.doc

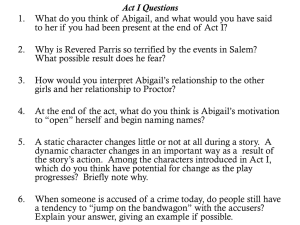

advertisement