SOCIOLGY 377 - Drugs, Crime & Law

advertisement

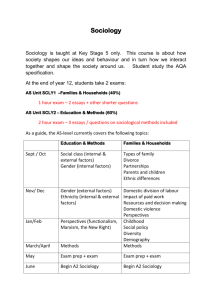

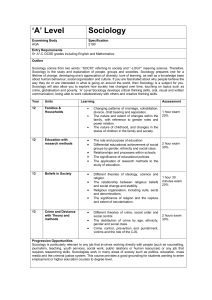

University of Wisconsin-Whitewater Curriculum Proposal Form #3 New Course Effective Term: 2147 (Fall 2014) Subject Area - Course Number: SOCIOLOGY 377 Cross-listing: Criminology (See Note #1 below) Course Title: (Limited to 65 characters) Drugs, Crime, and Law 25-Character Abbreviation: Drugs, Crime, Law Sponsor(s): Dr. Patrick K. O'Brien Department(s): Sociology, Criminology, and Anthropology College(s): Letters and Sciences Consultation took place: NA Yes (list departments and attach consultation sheet) Departments: Political Science and Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health Programs Affected: Is paperwork complete for those programs? (Use "Form 2" for Catalog & Academic Report updates) NA Yes Prerequisites: will be at future meeting SOCIOLOGY 276 OR CONSENT OF INSTRUCTOR Grade Basis: Conventional Letter S/NC or Pass/Fail Course will be offered: Part of Load On Campus Above Load Off Campus - Location College: Letters and Sciences Instructor: Patrick K. O'Brien Dept/Area(s): Sociology, Crim., and Anth Note: If the course is dual-listed, instructor must be a member of Grad Faculty. Check if the Course is to Meet Any of the Following: Technological Literacy Requirement Diversity Writing Requirement General Education Option: Select one: Note: For the Gen Ed option, the proposal should address how this course relates to specific core courses, meets the goals of General Education in providing breadth, and incorporates scholarship in the appropriate field relating to women and gender. Credit/Contact Hours: (per semester) Total lab hours: Number of credits: 0 3 Total lecture hours: Total contact hours: 48 48 Can course be taken more than once for credit? (Repeatability) No Yes If "Yes", answer the following questions: No of times in major: Revised 10/02 No of credits in major: 1 of 16 No of times in degree: Revised 10/02 No of credits in degree: 2 of 16 Proposal Information: (Procedures for form #3) Course justification: The United States has the harshest and most draconian drug laws in the Western world and incarcerates more of its citizens than any other country, mainly for drug related offenses. The laws pertaining to drugs are rarely based upon science, but rather on citizens’ fear of crime and drug users, propaganda, politics, and economic scapegoating. In its inception, the War on Drugs was meant to combat dangerous drugs and curb drug abuse. Yet, 40 years later the latent consequences of this war have been devastating for U.S. society. Through mandatory minimums, “three-strikes” laws, and the felonization of addiction, the Drug War has perpetuated mass incarceration, social degradation, and a permanent underclass of citizens. Currently, the U.S. is witnessing significant changes in drug war policies such as the legalization of marijuana in Colorado and Washington, the increasing legalization of medical marijuana across the U.S., the reduction in federal crack cocaine penalties, and the federal mandate to reduce prison overcrowding in California (mainly due to drug convictions). Furthermore, this year was the first in U.S. history that the majority of Americans (58%) supported the legalization of marijuana. This course will equip students with crucial knowledge and understanding into the intersection of drugs, crime, and law to be informed voters, criminal justice employees, lawyers, politicians, and teachers amidst the current and changing U.S. climate concerning drug policies. Finally, this course will also attend to LEAP essential learning outcomes in four ways: 1) Foster inquiry and analysis skills through the examination of empirical research about drugs, crime, and associated laws. 2) Enhance depth of critical thinking through reading, discussion, debate, and writing of timely and historical issues. 3) Broaden ethical reasoning through the examination of the application of punitive drug laws in relation to race/ethnicity, class, SES, and status. 4) Develop problem solving skills through the exploration of solutions and strategies to combat drug abuse and crime. Relationship to program assessment objectives: The implementation of this course supports eight assessment objectives for the criminology and sociology major. The implementation of this course supports objective #1for the criminology major (Identify different sources of US crime data and the trends and social patterns of criminality and victimization they reveal) by offering students current trends in drug use patterns, crime patterns, and explaining these trends. The implementation of this course supports objective #1 for the sociology major (demonstrate an understanding of sociology’s theoretical perspectives and core ideas including: the social construction of reality, culture and social structure, stratification and inequality, and order, conflict and change) as it examines the social construction of drug laws versus science, analyzes cultural and structural determinates of drugs and crime, investigates the impact of stratification and inequality on drug addiction, abuse, and victimization, and explores order, conflict, and change in relation to history, economics, discrimination, and drug laws. Second, the implementation of this course supports objective #4 for the criminology major (demonstrate analytical reasoning skills through a familiarity with criminological theory and research as applied to crime prevention and control policies) as it offers students theoretical perspectives on regulation and control, decriminalization, prohibition, and harm reduction strategies as applied to drug abuse prevention and drug control policies. Third, the implementation of this course supports objective #5 for the criminology major (identify causes of criminality and victimization for people of different class, racial-ethnic, gender, and age groups, as well as the different criminal justice responses to these groups) by explaining variations in drug use patterns across class, race, SES, education, age, gender, etc. Revised 10/02 3 of 16 Fourth, the implementation of this course supports objective #6 for the criminology major (identify the key stages of the criminal justice system and the organizational processes and discretionary-making that occur at each stage) by examining the drug users that are arrested, adjudicated, and incarcerated and the drug users that are weeded out of the criminal justice system. Fifth, the implementation of this course supports objective #7 for the criminology major (demonstrate knowledge of constitutional law as it relates to the operation of the criminal justice system) by examining the array of drug laws in our society. Sixth, the implementation of this course supports objective #13 and #6 for the sociology and criminology major (demonstrate ethical reasoning) by analyzing the ethical ramifications of the current drug laws in society. Budgetary impact: The implementation of this course will not have an adverse budgetary impact. This course will become part of Dr. O'Brien's regular rotation of courses. Course description: (50 word limit) This course examines the intersection of drugs, crime and the law in U.S. Society. The course utilizes the social constructionist perspective as it pertains to both legal and illegal drugs. Through the use of the constructionist perspective, this class will explore how believed truths and realities about drugs are often socially created, how the laws and the control of drugs has been constructed and maintained, how culture and history influence perceptions of drugs and crime, and how societal norms, values, and ideas concerning drugs are created and perpetuated. Course Objectives and tentative course syllabus with mandatory information (paste syllabus below): Drugs, Crime, and Law Fall 2014 Sociology 377 Prerequisite: Sociology 276 Class Syllabus Instructor: Patrick K. O’Brien Email: obrienp@uww.edu Office: 2117 Laurentide Hall Office Hours: Appointment WIKI page. Click for Appointment: https://wiki.uww.edu/facstaff/obrienp/index.php/Main_Page Additional Course Information: Available through D2L. REQUIRED TEXT: Adler, Patricia A., Peter Adler, and Patrick K. O'Brien. 2012. Drugs and the American Dream: An Anthology. Wiley Blackwell. **Listed as DAD in reading schedule Additional readings will be available on D2L or handed out in class. You are responsible for obtaining these readings. Revised 10/02 4 of 16 _______________________________________________________________________ COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course is an introduction to the sociology of drugs in our society. Specifically, we will be discussing the social constructionist perspective as it pertains to legal and illegal drugs in the United States. Through the use of the constructionist perspective, we will explore how believed truths and realities about drugs are often socially created, how the social order and the control of drugs has been constructed and maintained, how culture and history influence perceptions of drugs, and how societal norms, values, and ideas concerning drugs are created and perpetuated. The world of drugs is complicated and complex. The ingestion of chemicals for purposes of altering consciousness has been practiced in virtually all human cultures and in all epochs of history. Sometimes this has resulted in problems, sometimes not, depending on how a society defines and deals with drug use and on how well it takes care of its citizens. The first objective is to explore the social, cultural, political and economic processes that shape our understanding of and policies toward drugs. A second objective is to provide an historical and theoretical grasp of the social causes and consequences of the use and abuse of consciousness-altering substances. Third, the course attempts to stimulate critical thinking about policies that can reduce the harms associated with drug use and those associated with drug policy. Classes will include informal lectures and discussions. Lectures will integrate course readings and incorporate other material to present additional information. Discussions will help you learn to think sociologically and to deal critically with course materials. For us all to learn as much as possible from the course, regular class attendance and timely completion of reading assignments are essential. Ultimately what you get out of this course depends on what you put into it. The requirements for the course are designed to help you learn as much as possible and, especially, to help you learn to think sociologically about drugs, crime, and the law. LEARNING OBJECTIVES: 1. Examine the current and historical cultural patterns of drug use in U.S. society. The emphasis will be on providing a theoretical understanding of the initiation, use, and misuse of psychoactive substances. 2. Critically examine the structural and cultural factors that influence drug use, abuse, and addiction. 3. Investigate the complex relationship between drugs and crime. 4. Understand the latent and manifest consequences of polices of criminalization and prohibition. Develop the ability to critically reevaluate these polices and look to new solutions for the problem of drug abuse. 5. Investigate the social construction of drugs as a social problem. How are drugs defined as social problems and made salient in the public imagination? How does society choose which drugs to treat as social problems? 6. Study the laws and public policies intended to solve the social problem of drugs. What are the intended versus the real life effects of current laws and policies intended to curb drug use among the population? 7. Review the many treatment and prevention approaches currently used in society. What are the treatment and prevention strategies used today? Revised 10/02 5 of 16 COURSE POLICIES/REQUIREMENTS: Course Meetings: Please arrive to class on time, and remain for the entire class, do not begin packing up until after I have dismissed the class. If you have a conflict that requires you to arrive late or leave early, please inform me beforehand. Please turn off all cell phones. Please refrain from any disruptive behavior such as reading newspapers, doing other homework, engaging in side conversations, or sleeping. DO NOT SURF THE INTERNET, CHECK FACEBOOK, CHECK EMAIL, OR DO OTHER HOMEWORK. YOU WILL LOSE LAPTOP PRIVELEGES IN CLASS. Readings: You are required to complete all assigned readings and reading notes before class meets. The schedule of readings is available on D2L. Additional readings not found in the text can be found on D2L or will be handed out in class. Exams: There will be three exams in this course. Dates for exams can be found on the course schedule and the syllabus. Exams will consist of some combination of multiple choice and essay. The specifics of the exams will be discussed in detail as the course progresses. ABSOLUTELY NO MAKE UP EXAMS WILL BE GIVEN. Please check the exam schedule and NOTIFY ME IN ADVANCE of any conflicts you may have. The exams will cover each section of the course and will not be cumulative. Though the final exam will not be cumulative, you should still be able to apply and understand material from previous sections of the course. Attendance and Participation: You are required to attend and participate in all classes. I caution you that success in this class largely depends on your consistent effort and presence. It is my goal to create an environment where all members of the class feel comfortable sharing their ideas and thoughts. In order for this to be achieved it is crucial that all students behave in a respectful manner towards one another. Insensitive comments based on race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexual orientation, religion, ideas or beliefs will absolutely not be tolerated. University Policies: The University of Wisconsin-Whitewater is dedicated to a safe, supportive and nondiscriminatory learning environment. It is the responsibility of all undergraduate and graduate students to familiarize themselves with University policies regarding Special Accommodations, Academic Misconduct, Religious Beliefs Accommodation, Discrimination and Absence for University Sponsored Events (for details please refer to the Schedule of Classes; the “Rights and Responsibilities” section of the Undergraduate Catalog; the Academic Requirements and Policies and the Facilities and Services sections of the Graduate Catalog; and the “Student Academic Disciplinary Procedures (UWS Chapter 14); and the “Student Nonacademic Disciplinary Procedures" (UWS Chapter 17). “The UW System standard for work required per credit is that students are expected to invest at least 3credit hours of combined in-class and out-of-class work per week for each academic unit (credit) of coursework; thus, a 3-credit course will typically require a minimum of 9 hours of work per week (144 hrs./semester). Revised 10/02 6 of 16 GRADING: Your final course grade will be determined by the following course requirements: Exam I: 20% of your final grade. (WEEK 5) Essay portion distributed on TBA Exam II: 20% of your final grade. (WEEK 10) Essay portion distributed on TBA Exam III: 25% of your final grade. (WEEK 15) Essay portion distributed TBA Reading Notes: 20% of your final grade. Participation/Attendance/Group Work: 15% of your final grade. EXAM GUIDELINES: Exams will consist of two separate parts and will not be cumulative. On each exam you have the potential to earn 100 total points. PART I: Part one of each exam will consist of 35 multiple choice questions. Each question will be worth roughly 1.43 points. The entire portion will be worth 50 points. PART II: Part two of each exam will consist of take-home essay questions. The essay portion of the exam will be discussed in detail before the first exam. General directions are as follows: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Please TYPE your answers using 12-point Times New Roman font. Standard margins and double-spacing. Cover page that includes your name and SID number. The maximum page limit is 4 pages. Please include at the very least three citations from the readings or lecture, you need to cite in the paper (Ex. Goode 213 or O’Brien Lecture), but you may use the format you are most familiar with (e.g., MLA, APA, ASA). Please DO NOT over cite. By this I mean direct block quotes that use half of a page, useless citations, or so many citations that you never offer any explanation in your own words. 6. You need to draw on materials from lecture and the required readings to answer the essay questions. Your essays should exhibit the critical thinking skills you have developed on these issues. Please make sure you use correct spelling, grammar, and punctuation. You will be graded on the depth of knowledge and understanding of the material you convey to me through your answers. Revised 10/02 7 of 16 READING NOTES GUIDELINES (Drugs, Crime, and Law): “Why are we doing these?” Reading notes are an effective way of ensuring that you read and understood the chapters from class. Reading notes incentivize reading and rewards students who come to class prepared to discuss the material. When we have all read, we can spend class time understanding, discussing, and expanding on chapter material rather than simply reviewing it. What Makes Reading Notes Good or Bad? Reading notes that try and cover every piece of information are just as bad as reading notes that do not identify central or interesting concepts from the chapter. I want you to pull needles from a haystack. Your reading notes should cover (a few, but not all) of the chapter’s key ideas and topics. Things to Ask Yourself: What are some of the main points or concepts in this chapter? What concepts, ideas, or examples do I find most interesting? What are some central quotes that relate to the concepts I identified? Why are they important? What are some discussion questions that relate to the concepts I identified? What are some discussion questions I think would be interesting for the class? Directions: 1. Reading notes must be typed, printed, stapled, and include page numbers. You should print an extra copy or have your notes available on your laptop for class discussion. 2. Your reading notes must the outline form I have decided upon (discussed below) and the information must be presented in a way that is easy for the reader to understand and follow. 3. On the top left of the first page you are required to include your name, course name, class time, and the chapter number and name. 4. You are required to use Times New Roman 12-point font and one-inch margins. 5. You are required to upload your chapter outlines to D2L dropbox by the start of Monday class for the appropriate week. 6. Your notes should cover important material from the chapters. I expect your notes to cover more than just the first few pages of each chapter. Your notes should be 1-2 pages (do not exceed 2 pages). Main Concepts: 1-3 main points concepts, ideas, or arguments from the chapter o Think about what you thought was important to understand or what you found interesting. o Briefly explain the concept/idea. Why did you choose it? Quotes: 1-2 direct quotes that you thought were important from the chapter. o Why did you find these quotes important? Discussion: 2-3 discussion questions for the class or topics you want to know more about (these questions can be posed to the class, me, or just something you are curious about). Number your concepts, quotes, and discussion questions (e.g., 1,2,3, etc.) Each main point, direct quote, and discussion question must cite the page number(s) so you can refer back to the appropriate pages during class if necessary. Always bring your book to class! Revised 10/02 8 of 16 YOU SHOULD ALWAYS BE PREPARED TO DISCUSS YOUR READING NOTES IN CLASS and BRING YOUR BOOK TO CLASS. Example: Patrick O’Brien Course name, class time Chapter 1: Perspectives on the Problem of Crime Main Concepts 1. Fear of crime is a complex issue. (2) Our view of crime is not always drawn from reality. Research indicates that the mass media, politicians, and law enforcement officials are all major sources of our knowledge about crime. They play a large role in shaping our perceptions of crime, ideas about criminals, and our fears of certain crime. (3) Research indicates that the elderly tend to be more fearful of crime than the young, even though they are less likely to be victims. Women are more likely than men to experience sexual assault and domestic violence, yet they also express greater fear of other crimes as well. (2) Typically we think of criminals as persons who are fundamentally different from the rest of us. Few of us, however, are paragons of virtue. (3) I think fear of crime can really impact society. It creates panic among the public and leads to harsh laws. We are only afraid of certain crimes and this really serves to create the current society we live in. Quotes: 1. “Reinarman and Levine understand that crack is a dangerous drug, but note that exaggerated drug scares are an ineffective way to solve the drug problem and may even increase interest in drug use.” (13) I think drug scares create fear and panic, they get everyone riled up when we need to look at the problem rationally. 2. “According to C. Wright Mills (1959), a sociological imagination helps us see the ways in which personal or private troubles are related to public issues.” (21) I think we live in a very individualistic society, we are impacted so much by our place in society, but we often blame individuals and ourselves for issues that are part of larger society. Discussion: How are drug scares, as a form of moral panic, able to associate allegedly “dangerous drugs” to a perceived “dangerous class?” Why do certain members of society do this? Why do we see criminals as fundamentally different from us? What role does the media play in these views? Revised 10/02 9 of 16 Grading Rubric: Notes will be handed back to you with marks on the top right corner of the first page. (✔+ ✔ ✔-) These marks will represent how well you identified main points and information from the chapter, organized your notes clearly, followed formatting directions, and demonstrated reading and effort. Identifies main topics ✔+ 3pts ✔ 2pts ✔1pt Organized Clearly, Follows Formatting Follows Directions Demonstrates Reading and Understanding Notes cover key points and topics of the chapter with enough detail for the reader to understand them. Notes are not overly detailed or overly simplistic. Quotation directions are followed. Well thought out discussion questions. Notes are easy to read and use a clear outlining style. Formatting directions are followed. Notes are uploaded to D2L. After reading it’s clear the student has read and has an understanding of central topics of the entire chapter. Student has exhibited good effort on the chapter outline. Notes cover some main points of the chapter. Notes are both too simple and vague or overly detailed. Quotation directions are followed. Adequate discussion questions. Notes are mostly clear and easy to read. The outline style was inconsistent, but able to be followed. Formatting was inconsistent. Notes are uploaded to D2L. After reading it’s clear that the student read the majority of the chapter, adequately understood main topics, and spent adequate time on the outline. Notes do not identify important or main ideas from the chapter. Quotation directions are not followed. Discussion questions do not reflect main concepts and/or are not well thought out. Notes are difficult to read and/or the outlining style is a barrier to reading. Formatting was consistently wrong. Notes are NOT uploaded to D2L. After reading it’s clear that the student did not adequately read the chapter, understand/identify main topics, and/or apply sufficient effort on the outline. Submission Schedule: There will be a total of 11 reading notes; you only need to turn in 9 of them for grading. This is designed to allow for student illness, family emergencies, etc. All reading notes must be printed and turned in during class time. All reading notes must be turned in at the end class (PRINTED AND STAPLED) on Monday. You should keep a separate copy (printed or on your computer) to refer to your notes during Wednesday and Friday class. No emailed papers will be accepted in this class. Collaboration: Students are expected to do their own work and write notes that are their own intellectual work. No copy/pasting your classmates work. Copying is academically dishonest and will be prosecuted accordingly. D2L will check your chapter notes for plagiarism from fellow classmates. YOU ARE NOT ALLOWED TO SIMPLY LIST AND DEFINE TERMS; THIS WILL RESULT IN AN AUTOMATIC ZERO. __________________________________________________________________________________ Revised 10/02 10 of 16 COURSE GRADE SCALE: A=100-90 B=80-89 C=79-70 D=69-60 F=59-0 “Plus” or “minus” may be assigned at the instructor’s discretion and will largely depend upon your presence and participation in the class. By attending this class you are agreeing to the “terms” outlined in the syllabus. I hold the right to change the syllabus throughout the semester to respond to class concerns or situations. If you find any of this disagreeable, drop this class. TENTATIVE COURSE SCHEDULE: This course schedule provides a tentative framework for the course throughout the Fall 2014 semester. It simply provides a general idea of the required readings and the date of ths exams. This schedule is subject to change as the course progresses to adapt to the needs and direction of the course. READINGS MAY BE ADDED PERIODICALLY. Week 1 Introduction to the Course & Drug Basics Sociological Perspectives on Drugs & Drug Basics Goode CH 1 (D2L) & DAD (Part I, Reading 4, p24) Week 2 Sociological Perspectives on Drugs & Drug Basics cont’d Goode CH 2 (D2L) & (Part I, Reading 5, p33) Week 3 Legal Drugs: Alcohol and Psychotherapeutic Drugs DAD: (Part II, Reading 19, p152), (Part II, Reading 22, p184) Alcohol and Psychotherapeutic Drugs DAD: (Part I, Reading 3, p18), (Part II, Reading 16, p120) Week 4 Marijuana and Hallucinogens DAD: (Part III, Reading 25, p215), (Part III, Reading 28, p240) Stimulants: Amphetamines, Methamphetamine, Cocaine, & Crack Goode CH 10 (D2L) & DAD: (Part I, Reading 8, p55) Week 5 Review Revised 10/02 11 of 16 Distribution of Essay Exam Portion EXAM 1 and Essay Due in Hard-Copy Form Week 6 Documentary Film and Discussion Week 7 Heroin and the Opiates Goode CH 11 (D2L) & DAD: (Part II, Reading 9, p64) Theories of Drug Use Goode CH 3 (D2L) Week 8 Drug Using Subcultures and Lifestyles DAD: (Part II, Reading 17, p131) and (Part III, Reading 29, p249) Social Research & Patterns of Illegal/Legal Drug Use Goode CH 6 & CH 7 (D2L) Week 9 Drugs in the Media & Drug Scares DAD: (Part I, Reading 6, p40) Drugs and Crime DAD: (Part III, Reading 32, p277; Reading 35, p305; Reading 31, p266) Week 10 Review Distribution of Essay Exam Portion EXAM II and Essay Due in Hard-Copy Form Week 11 Film/Drug Prohibition and Violence War on Drugs Discussion DAD: (Part III, Reading 34, p295) and (Part IV, Reading 43, p378) Week 12 War on Drugs/Drug Control/Drug Prevention/Treatment Programs Goode CH 14 (D2L) & DAD: (Part IV, Reading 44, p386) Drug Policies/Drug Prevention Programs Cont’d Goode CH 13 (D2L) & DAD: (Part VI, Reading 45, p391) Week 13 Drug Policies/Drug Prevention Programs Cont’d Revised 10/02 12 of 16 DAD: (Part IV, Reading 36, p316 and Reading 37, p327) Legalization, Decriminalization, and Harm Reduction Goode CH 15 & DAD: (Part IV, Reading 40, p351) Week 14 Addiction, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Civil Rights, Knowing Your Rights Week 15 & Final Exam Week Review and concluding discussion/remarks Distribution of Essay Exam Portion Final Exam Bibliography Bolded entries are available to students online via UW-Whitewater institutional access ** entries are books available to students directly through the UW-Whitewater library Adler, Patricia A. 1985. Wheeling and Dealing: An Ethnography of an Upper-Level Drug Smuggling Community. New York: Columbia University Press. Dealing and Adler, Patricia A. and Peter Adler. 1983. “Shifts and oscillations in deviant careers: The case of upper-level drug dealers and smugglers.” Social Problems 31(2):195–207. Armstrong, Elizabeth A., Laura Hamilton, and Brian Sweeney. 2006. “Sexual Assault on Campus: A Multilevel, Integrative Approach to Party Rape.” Social Problems 53(4):483–99. Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2007. “Emerging Adulthood: What Is It, and What Is It Good For?” Child Development Perspectives 1(2):68–73. Benavie, Arthur. 2009. Drugs: America's Holy War. New York: Routledge. **Bogazianos, Dimitri A. 2012. 5 Grams: Crack Cocaine, Rap Music, and the War on Drugs. New York: NYU Press. Capraro, Rocco L. 2000. “Why college men drink: Alcohol, adventure, and the paradox of masculinity.” Journal of American College Health 48(6):307–15. Caulkins, Jonathan P., Bruce Johnson, Angela Taylor, and Lowell Taylor. 1999. "What Drug Dealers Tell Us About Their Costs of Doing Business." Journal of Drug Issues 29(3):323-40. Caulkins, Jonathan P. and Peter Reuter. 1998. "What Price Data Tell Us About Drug Markets?" Journal of Drug Issues 28(3):593-612. Conrad, Peter. 1979. “Types of Medical Social Control.” Sociology of Health and Illness 1(1):1–11. Conrad, Peter. 1992. “Medicalization and Social Control.” Annual Review of Sociology 18:209–32. Faupel, Charles E. 1991. Shooting Dope: Career Patterns of Hard-Core Heroin Users. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. Revised 10/02 13 of 16 **Fisher, Gary L. 2006. Rethinking Our War on Drugs: Candid Talk About Controversial Issues. Westport, CT: Praeger. Ford, Jason A. and Ryan D. Schroeder. 2009. "Academic Strain and Non-Medical Use of Prescription Stimulants Among College Students." Deviant Behavior 30(1):26-53. Global Commission on Drug Policy. 2011. "The War on Drugs: A Report of the Global Commission on Drug Policy." Retrieved September 9, 2011 (http://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/Report). Goldstein, Paul J. 1985. “The Drugs/Violence Nexus: A Tripartite Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Drug Issues 15(4):493–506. Goodhart, Fern Walter, Linda C. Lederman, Lea P. Stewart, and Lisa Laitman. 2003. “Binge Drinking: Not the Word of Choice.” Journal of American College Health 52(1):44–46. **Gray, James P. 2011. Why Our Drug Laws Have Failed and What We Can Do About It: A Judicial Indictment of the War on Drugs. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. Ham, Lindsay S. and Debra A. Hope. 2003. “College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature.” Clinical Psychology Review 23(5):719–59. Hathaway, Andrew D., Natalie C. Comeau, and Patricia G. Erickson. 2011. “Cannabis Normalization and Stigma: Contemporary Practices of Moral Regulation.” Criminology and Criminal Justice 11(5):451–69. Herman-Kinney, Nancy J. and David A. Kinney. 2013. “Sober as Deviant: The Stigma of Sobriety and How Some College Students ‘Stay Dry’ on a ‘Wet’ Campus.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 42(1):64–103. **Huggins, Laura E. 2005. Drug War Deadlock: The Policy Battle Continues. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. Levy, Judith. A. and Tammy Anderson. 2005. “The Drug Career of the Older Injector.” Addiction Research & Theory 13(3):245–58. Luckenbill, David F. and Joel Best. 1981. “Careers in Deviance and Respectability: The Analogy’s Limitations.” Social Problems 29(2):197–206. **MacCoun, Robert J. and Peter Reuter. 2001. Drug War Heresies: Learning From Other Vices, Times, and Places. New York: Cambrdige University Press. Maloff, Deborah, Howard S. Becker, Arlene Fonaroff, and Judith Rodin. 1979. “Informal Social Controls and their Influence on Substance Use.” Journal of Drug Issues 9:161–84. Martin, Christopher S., Patrick R. Clifford, and Rock L. Clapper. 1992. "Patterns and Predictors of Simultaneous and Concurrent Use of Alcohol, Tobacco, Marijuana, and Hallucinogens in First-Year College Students." Journal of Substance Use 4(3):319-26. McBride, Duanne C., Yvonne Terry-McElrath, Henrick Harwood, James A. Inciardi, and Carl Leukefeld. 2009. “Reflections on drug policy.” Journal of Drug Issues 39(1):71–88. McCabe, Sean Estaban, James A. Cranford, Michele Morales, and Amy Young. 2006. "Simultaneous and Concurrent Polydrug Use of Alcohol and Prescription: Prevalence, Correlates, and Consequences." Journal of Studies on Alcohol 67(4):529-37. Mohamed, Rafik A. and Erik D. Fritsvold. 2010. Dorm Room Dealers: Drugs and the Privelees of Race and Class. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. Montemurro, Beth and Bridget McClure. 2005. “Changing Gender Norms for Alcohol Consumption: Social Drinking and Lowered Inhibitions at Bachelorette Parties.” Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 52(5-6):279–88. Revised 10/02 14 of 16 O'Grady, Kevin E., Amelia M. Arria, Dawn M.B. Fitzelle, and Eric D. Wish. 2008. "Heavy Drinking and Polydrug Use Among College Students." Journal of Drug Issues 38(2):445-66. Page, Bryan J. and Merrill Singer. 2010. Comprehending Drug Use: Ethnographic Research at the Social Margins. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. **Payan, Tony. 2006. Cops, Soldiers, and Diplomats: Explaining Agency Behavior in the War on Drugs. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. Peralta, Robert L. 2002. “Alcohol Use and the Fear of Weight Gain in College: Reconciling Two Social Norms.” Gender Issues 20(4):23–42. Peralta, Robert L. 2005. "Race and the Culture of College Drinking: An Analysis of White Privilege on Campus." Pp. 127-41 in Cocktails and Dreams: Perspectives on Drug and Alcohol Use, edited by Wilson R. Palacios. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Peralta, Robert L. 2007. “College Alcohol Use and the Embodiment of Hegemonic Masculinity among European American Men.” Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 56(11-12):741–56. **Provine, Doris Marie. 2007. Unequal Under Law: Race in the War on Drugs. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Ravert, Russell D. 2009. “‘You’re Only Young Once’ Things College Students Report Doing Now Before It Is Too Late.” Journal of Adolescent Research 24(3):376–96. Reuter, Peter. 2009. “Systemic Violence in Drug Markets.” Crime, Law and Social Change 52(3):275–84. Robinson, Matthew B. and Renee G. Scherlen. 2007. Lies, Damned Lies, and Drug War Statistics: A Critical Analysis of Claims made by the office of National Drug Control Policy. New York: SUNY Press. Room, Robin, Benedict Fischer, Wayne Hall, Simon Lenton, and Peter Reuter. 2010. Cannabis Policy: Moving Beyond the Stalemate. New York: Oxford University Press. Tewksbury, Richard and Elizabeth Mustaine. 1998. “Lifestyles of the wheelers and dealers: Drug dealing among American college students.” Journal of Crime and Justice 21(2):37-56. **Valentine, Douglas. 2004. The Strength of the Wolf: The Secret History of America’s War on Drugs. New York: Verso. **Vander Ven, Thomas. 2011. Getting wasted: Why college students drink too much and party so hard. New York: NYU Press. Vecitis, Katherine Sirles. 2011. “Young Women’s Accounts of Instrumental Drug Use for Weight Control.” Deviant Behavior 32(5):451–74. Young, Amy M., Michele Morales, Sean Esteban McCabe, Carol J. Boyd, and Hannah D’Arcy. 2005. “Drinking Like a Guy: Frequent Binge Drinking among Undergraduate Women.” Substance Use & Misuse 40(2):241–67. **Zinberg, Norman E. 1984. Drug, Set, and Setting: The Basics for Controlled Intoxicant Use. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Revised 10/02 15 of 16 Revised 10/02 16 of 16