Bobbins and Bibles Child Labor, The Sunday School Movement and

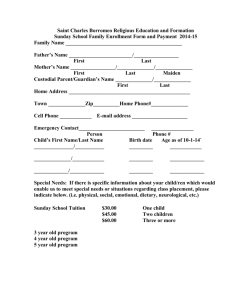

advertisement

Bobbins and Bibles Child Labor, The Sunday School Movement and Industrial England 1780-1840 Nancy Bell Eudy Spring ISD Houston, Texas NEH Summer Seminar 2000 Historical Interpretations of the Industrial Revolution in Britain University of Massachusetts Dartmouth at the University of Nottingham 2 From approximately 1780 to 1840 the expansion of factory textile production in industrial England created a new environment for working children, one viewed by many as a necessary evil and one which eventually launched a reform movement that encompassed compulsory education. Predating that reform by nearly three-quarters of a century was another legacy of child labor, the Sunday school movement. An examination of conditions in factories crowded with young full-time workers shows the connection between labor and the Sunday schools. While the employment of children varied from industry to industry as well as from district to district, it was primarily the growth of textile factories that made aspects of child labor so controversial in the late 1700s and early 1800s. In the 18th century popular recreations included fairs, games, and dances, and participation in these activities by children would not have been possible if their hours of work in the home had rivaled the hours imposed by the factory. Labor was a certainty for most children at the time, but child labor changed dramatically with factory work. No one would question that the use of children in agriculture could be just as difficult as the employment of children in factories, but the transition from toil within the family circles to the impersonal mill was a harsh one (Horn,1994). Specialization itself required monotonous tasks for ten or more hours. When working at home, whether assisting with weaving or tending livestock, the child’s work was doubtlessly affected by his parents moods, the cycles of farm life, the demands of cottage industry, and to some degree his own abilities. By contrast, the factory offered no leniency or relief, for “machinery dictated environment, discipline, speed and regularity of work and working hours, for the delicate and strong alike” (Thompson, 1963). In the earliest days of industrialization, children were used partly because of a shortage of labor, but later their employment was preferred because of the type of jobs which machine 3 production required. Certainly the fact that the young workers were cheap was a contributing factor as well. As manufacturing moved to the mill, the children moved with it, no longer under the watchful eye of parents within the family economy. Children as young as 7, 8, and 9 were forced to meet demands of power-driven machinery for up to fourteen hours a day. In 1816 nearly 20 per cent of the workers in the cotton industry were under the age of 18. In that same year children accounted for 70 per cent of the labor force at the Gregs' Quarry Bank Mill in Styal, Cheshire, one of the notable exceptions to the relentlessly bleak and harsh existence for factory children. Other comparatively humane and custombuilt industrial settlements were Richard Arkwright’s Cromford in Derbyshire and Jedidiah Strutt's Belper Village (Watney, 1998). Unfortunately, men like Arkwright, Samuel Greg, and Strutt who believed that wealth brought responsibility were not typical mill owners. In one of Manchester's largest mills, McConnel and Kennedy's, 40 per cent of the labor force was between 8 and 15 years of age (Cruickshank, 1981). By 1835 the under 13s comprised 29.5 per cent of the labor force, in spite of technological advances that reduced the need for juvenile workers. The textile areas of Yorkshire, Cheshire, and Lancashire employed the greatest numbers of children. As ‘hands’ they were called and dismissed by factory bells and subjected to strict, often severe discipline, supervised by strangers in many cases (Nardinelli, 1990; Horn, 1994). Such a system, as might be expected, exploited children, and protesters like Richard Oastler, a mill operative of Yorkshire and a founder of the Factory Movement, advocated shorter hours for children in factories. He spoke emotionally and wrote just as passionately in a series of letters published in 1830 in the liberal Leeds Mercury (Ward, 1970). Evidence examined in the Report of the Select Committee on Factory Children’s Labour, Vol. XV, 1830-1832 vividly 4 exposed the cruelty rampant in the textile mills. Young workers described workdays beginning at three o’clock in the morning and ending at ten at night. Testimony revealed extremely strict discipline and numerous accidents and deaths caused by fatigue, hunger and unsafe machinery (Harrison, 1965; Horn, 1994). Every factory produced its quota of cripples (Dodd, 1842). The country gentry, with their inherent ability to protect the poor, appeared oblivious to serious abuses inflicted on the child workers. In their eyes the young laborers were”busy and productive” (Thompson, 1963). Above all, they were cheap and employable almost from the time they could crawl. Reformers rarely argued that child labor should be abolished; instead they urged regulation so that the worst abuses would be eliminated. Influencing the debate were two opposing view of childhood, the older and more prevalent philosophy which held that a child was innately sinful, as was all humanity, and its antithesis, a second view which stressed the natural goodness and innocence of the young. Efforts to alleviate the idleness which resulted in “moral weakness” involved employment of extremely young children in impersonal factories. The changes these factories brought to production ensured that children were important and necessary contributors to the economic system (Hammonds, 1917). Those made wealthy by the labor of children promoted the idea that child laborers were content and busy, their endeavors successfully keeping idleness at bay within the confines of the factory. A rising tide of reformers criticized these rich industrialists, and acrimonious debates followed between those seeking improvements for children in the work place and those content with the status quo. Inevitably, education became a major topic of contention. While several mill owners advocated limited educational objectives for their employees as a means of instilling the necessary discipline required by the dictates of the machine, they were convinced that factory work could be mastered only if the “hands” started at a very early age, a condition which precluded any structured daily educational 5 opportunities. They wanted sufficient instruction to promote the discipline essential for successful factory work but not enough to inspire workers to question their situation or join those who were clamoring for change. Eventually the fury of reformers like Michael Sadler, a Tory Radical, and two Benthamites, Edwin Chadwick and Southwood Smith, who advocated a broader and more inclusive system of education, prevailed and the Factory Act of 1833 was passed. Other men of conscience who fought heroically for reform included Charles Fox, Henry Grey Bennett, Samuel Whitbread, and Lord Ashley, the future Earl of Shaftesbury and a Tory humanitarian who served as chairman of a House of Commons Select Committee on the Working of the 1833 Act. Under this act, children younger than 9 would not be allowed to work in textile factories; workers between 9 and 18 could not work more than eight hours a day and they were to receive at least three hours of schooling each day. The act applied only to young people in textile production, and further provided that adolescents between 13 and 18 could not work more than twelve hours a day. Probably the most important provision was that four factory inspectors would be appointed to enforce the law. Unlike its predecessors, the Factory Acts of 1802 and 1819, the local magistrates were not the ones responsible for its enforcement (Arnstein, 1976; Horn, 1994). Generally speaking, social improvements had little impact until after the mid-1800s; elementary education did not become compulsory until 1876, but the conscience of men such as Ashley enabled factory children to receive a rudimentary education. To exert more control over the workers and also to instill moral and religious values, some manufacturers established Sunday schools for instruction on the workers’ one free day. In many of these schools the primary focus was not to teach children to read but rather to provide a type of training ground to produce docile and disciplined workers. Other schools were deeply committed to the 6 teaching of reading since it was necessary for Bible reading but they avoided writing and math as many of the schools benefactors feared “it would make them (the poor) discontented with their lot and aspire to be masters instead of servants” (Collins, 1996; Holdt, 1938). Additionally, some people opposed schools for laborers because acquisition of literate skills “would make the working classes receptive to radical and subversive literature” (Sanderson, 1991). The Sunday schools were not the first established schools for children, but in the context of the factory workplace they assumed a new importance--both to supporters and opponents. In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries there were a few instances of charity schools in England, and religious catechizing of children was an element of faith at the very creation of religion. One of the earliest Sunday schools was established by Theophilus Lindsey at his vicarage in Catterick in 1764 or 1765 before he became a Unitarian. Like most Sunday schools of today, Lindsey’s provided purely religious instruction. The inspiration for a second type of Sunday school that would concern itself with the teaching of reading as well as religious matter apparently motivated several likeminded men and women about the same time, the middle of the eighteenth century. Thus, there are rival claimants for the honor of being the founder of the Sunday school movement (Holdt, 1938). Certainly one of the most active patrons and the one most frequently referred to as the Father of the Sunday School Movement was Robert Raikes, a printer and editor of the Gloucester Journal who founded a school in 1780 to provide children with “scraps of information” in addition to teaching them to read the Bible (Lynd, 1968). Raikes’ interest in education came from his visit to the pin manufacturing area of Gloucester where he saw dirty ragamuffins cavorting in the streets engaged in all sorts of mischief when not employed, many of whom had been abandoned by their parents who probably felt totally abandoned 7 themselves. The Journal enjoyed a wide circulation and Raikes’ articles describing the damage and disruption caused by children permitted to run wild on the Sabbath and the subsequent beneficial and calming effects of Sunday schools were reprinted in other newspapers. Raikes stressed that the only requirement for attendance was a clean face and combed hair, nothing more. Along with clergymen like the Rev. Thomas Stock of Gloucester, Raikes supported the foundation of the Society for the Establishment and Support of Sunday Schools in 1785 (Collins, 1996). Because of his trade, Raikes could publish, import and distribute the primers, readers, spelling books, and copies of scripture so important to the movement. The Sunday School Union organized in 1803 was a further testimony to his effectiveness in transforming children of industrial England. If, as Raikes once commented, “the world marches forth on the feet of little children,” huge strides were being made in the manufacturing towns like Stockport which had a Sunday school in 1784., one of the largest and most famous. It “was open to any children who labour for their living in the week-day, are seven years old or upwards, and not afflicted with any contagious disease.” Sunday hours were from nine o’clock until six with breaks for “dinner and divine services.” A scant year later over 250,000 children were attending Sunday school throughout England, including 5,000 in Manchester, where, in August, 1786, the magistrates passed a lengthy resolution lamenting an apparent crime wave. They were counting on the recently established Sunday schools to “restore the moral integration so obviously lacking” (Bohsted, 1983). That same year over 400 children were studying at the Macclesfield Sunday school (Collins, 1996). Teachers urged restraint on older scholars in the year of Peterloo and members were admonished to “do their duty in that state of life which it shall please God to call them” (Cruickshank, 1981). Mill owners welcomed Sunday schools, primarily financed by subscriptions and endowments, because they instilled 8 punctuality and discipline plus a dose of morality without interfering with the work schedule of six full days. Mrs. Sarah Trimmer, a reformer and educational writer, applauded the goals of the Sunday school sponsors when she wrote in 1787: Wherever Sunday-schools are established, instead of seeing the street filled on the Sabbath-day with ragged children engaged at idle sports, and uttering oaths and blasphemies, we behold them assembling in schools, neat in their persons and apparel, and receiving with the greatest attention instruction suited to their capacities and conditions (Cunningham, 1991) Remaining in one’s station was a widespread hope for the factory owners and other industrialists who did not want to lose cheap laborers, especially children, who might be tempted to challenge their fate if too much education were provided. Other early leaders were the More sisters, Hannah and Martha, both representatives of the middle-class “do-gooders” who claimed that the purpose of the schools was to instill “habits of industry and piety among the lower classes” Hannah More's religious tracts exuded condescension and she believed that it was a grievous error to regard children as innocent beings. Rather, their “corrupt nature and evil dispositions” required strict discipline and instruction, presumably an even greater need if they labored in textile factories (More, 1799). At least through the first half of the nineteenth century the schools played a significant role in secular as well as religious instruction (Mitch, 1999). Sunday schools were created under the auspices of practically every church and chapel, fueled by the evangelical movement. A particular church or chapel could be assured of increased membership if the children received instruction in a specific faith or creed. Sunday schools spread so rapidly that there were 7,000 by 1800 (Holdt, 1938). In 1803 the inaugural meeting of the National Sunday School Union was held at Rowland Hill’s Surrey Chapel and by 1810 there were approximately 25,000 students in the Nottingham District alone participating in 9 the Sabbath lessons (White, 1864). Children already absorbed into industry because of abject poverty were working six full days and could only snatch at education on the seventh day, but even that short time was begrudged them by many critics who feared that educating the poor would endanger existing institutions (Marshall, 1956). Another obstacle was indifference. In the 1820s dozens of professional men and gentlemen were living in large manufacturing centers and amazingly oblivious to the many abuses taking place a few hundred yards away (Thompson, 1963). Still, the respectable poor sent their children to Sunday schools and they were supported in their efforts by some industrialists like John Horrocks of Preston who paid employees at his textile mill to clear the streets on Sundays and check that children were in attendance at a Sunday school. The relative prosperity of the years after 1819 allowed factory families to provide their children with decent footwear and clothing for Sunday school. Attendance each Sunday encouraged special efforts in washing and hair-combing, and occasional refreshments engendered strong loyalty among the students (Cruickshank, 1981). Curious details abound regarding specific Sunday schools. At Lye in Worcestershire, for example, until 1850 new bonnets were presented to the female pupils annually in a special ceremony while at Hale in Cheshire 34 children received a penny each for not attending a local fair where they might have witnessed scenes of inebriated excitement. The school at Exeter offered math instruction during the week as a reward for those students who had attended class on the previous Sunday (Holdt, 1938). In particular the Methodists were responsible for eventually introducing writing into their Sunday schools, reversing their 1814 ban shared by the Established Church and other Nonconformist sects, although some ministers like Jabez 10 Bunting whose uncompromising Sabbatarianism led him to regard “writing as an awful abuse of the Sabbath” strongly opposed it (Thompson, 1963). The Methodist schools featured men and women who excelled in oratory, leadership, and organization. Even though their teachings stressing submission were generally unfavorable to working class movements, their impact on the members of an oppressed society was helpful in many ways. The workers became better citizens and probably better rebels in some instances (Hammonds, 1917). By the 1840s Sunday education of the poor was widely accepted and two million working class children were being taught by teachers predominantly from the same class. During a working-class childhood, three or four hours of instruction each week for an average of four years had a major impact on mass literacy in nineteenth century England. In many of the Sunday schools, classes were small and students were ability-grouped. Leaders like Raikes, benevolent proponents of the philanthropic establishment, were gradually replaced by working men and women who transformed the schools into agencies of self-improvement (Laqueur, 1976; Stephens, 1998). The Sunday schools spawned an assortment of helpful associations with even libraries and savings banks attached to several friendly societies and sick clubs covered only adult workers, but factory children could enroll in Sunday school societies like the one at Ardwick that paid out relief in illness and also provided a death grant, a grim reminder of the nature of their toil (Cruickshank, 1981). A community spirit characterized the Sunday schools and many featured the model of the benevolent teacher as an “older, wiser, and steadier friend.” Teachers were urged to be kind and cheerful and possess an unerring “devotion to Christ” (Laqueur, 1976). In marked contrast to these decorous models of beneficence, other teachers such as those at Caistor were admonished “to tame the ferocity of their (students) unsubdued passions. . . to subdue the stubborn 11 rebellion of their will-to render them honest, obedient, courteous, industrious, submissive, and orderly. . .” (Thompson, 1963). Their instructional emphasis would eventually revert to providing solely religious instruction as more Sunday schools affiliated with particular churches, and reform legislation improved workers lives, but for a time they made a crucial difference to child laborers confined to the factories of industrial England. Until compulsory education on a daily basis became a reality, they were the means by which generations of children were instructed and disciplined, and they had a definite impact on the habits of those who attended. Even the least exclusive of the Sunday schools insisted on standards of cleanliness and neatness. Regardless of whether they were middle-class conservative institutions created for the reform of child laborers desperately in need of whatever help they could receive or the creation of a working-class culture of self-reliance and self-respect, their influence remains undeniable. Sunday schools provided part-time education to children employed full-time in often degrading circumstances, arguably enhancing their standard of living. Support of these schools was no small tribute to the general belief that even the overburdened factory children should at least be able to read. The Sunday schools successor, the Ragged Schools, concentrated on educating the young working poor in the fundamentals of reading, writing, and math with their religious enlightenment again the domain of the Sunday schools. In part Sunday schools had begun as a manifestation of faith in the efficacy of education and the malleability of human nature. From four schools in Gloucester, the Sunday school movement flourished with a wide geographical and religious distribution that spread rapidly across England. In the Midland cities of Birmingham and Nottingham, the textile towns of West Riding and Lancashire, and the rural villages of the Cotswolds, Sunday schools were 12 popular and offered educational, religious, and recreational services not found elsewhere. Their main legacy is that they gave child laborers of industrial England an opportunity to become literate and escape, if only for a few hours, the monotony of their weekday lives. BIBLIOGRAPHY Arnstein, Walter L. (1976) Britain Yesterday and Today (Lexington, Massachusetts). Baines, Edward (1835) The History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain (London). Bohstedt, John (1983) Riots and Community Politics in England and Wales 17901810 (Cambridge, Massachusetts). Collins, LouAnne (1996) Macclesfield Sunday School 1796-1996 (Macclesfield). Cunningham, Hugh (1991) The Children of the Poor. Representations of Childhood Since the Seventeenth Century (Oxford). Cruickshank, Marjorie (1981) Children and Industry. Child Health and Welfare in North-West Textile Towns During the Nineteenth Century (Manchester). Dodd, William (1842) The Factory System Illustrated: A Narrative of Experience and Suffering of William Dodd, Factory Cripple, Written by Himself, 1841 (London). Hammond, J. L. and Barbara (1917) The Town Labourer 1760-1832 The New Civilization (London). _________(1930) The Age of the Chartists 1832-1854: A Study of Discontent (London). Harrison, J. F. C. (1965) Society and Politics in England 1780-1960 (New York). Holdt, Raymond V. (1930) The Unitarian Contribution to Social Progress in England (London). Horn, Pamela (1994) Children’s Work and Welfare, 1780-1890 (Cambridge). 13 Laqueur, Thomas (1976) Religion and Respectability. Sunday Schools and Working Class Culture 1780-1850 (Yale). Lynd, Helen Merrell (1968) England in the Eighteen-Eighties (London). Marshall, Dorothy (1956) English People in the 18th Century (London). Mitch, David, The Role of Education and Skill in the British Industrial Revolution Mokyr, Joel, (ed.) (1999) The British Industrial Revolution (Boulder). Nardinelli, Clark (1990) Child Labor and The Industrial Revolution (Bloomington). Stephens, W. B. (1998) Education in Britain, 1750-1914 (London). Thompson, E. P. (1963) The Making of the English Working Class (London). Ward, J. T. (1970) The Factory System, Vol. II: The Factory System and Society (New York). Watney, John (1998) The Industrial Revolution (Hampshire). White, Frances (1864) Nottinghamshire, History, Gazetteer, and Directory of the County, and of the Town of Nottingham (Sheffield). 14 15 16 17 18