Janet Tomiyama - The American School in Japan

advertisement

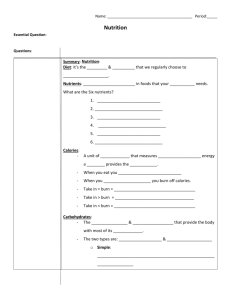

features SCIENCE J anet, who is an assistant professor of health psychology at UCLA and the director of the DiSH (Dieting, Stress, and Health) Lab answers our burning questions about the link between stress and weight gain and how dieting the wrong way can make us less healthy. Were there any particular experiences at ASIJ that influenced your career choice? ASIJ is a wonderful place, because it exposed me not only to US and Japanese culture but also to many cultures throughout the world. This cross-cultural viewpoint was the jumping-off point for my very first research paper studying cross-cultural differences in parenting styles. This segued into a research study looking at the role of parenting/family styles in eating disorder risk. Until that point, researchers thought that “enmeshed” families—those that are characterized by extreme closeness— put individuals at risk for anorexia nervosa. Something about that didn’t seem right to me, since that seemed to describe family relationships in Japanese and many other so-called collectivistic cultures that I had been exposed to, and eating disorder prevalence was lower in those cultures. I gathered some data, and found that among these enmeshed families, individuals from collectivistic cultures seemed to be protected from the risk of eating disorders. dish Dr Janet Tomiyama ’97 on how to stay healthy in a world full of stress 18 the ambassador FALL 2013 up A key component of your research is your multidisciplinary approach. After majoring in social psychology for your undergraduate studies at Cornell and Masters at UCLA, you began to focus on health psychology for your PhD research. What initially interested you in the intersection of health and psychology? My research interest in eating disorders quickly gave way to research interests in eating in general. What makes people eat, and what makes people not eat (i.e., diet)? Why do individuals diet, and is dieting really that healthy for you? Dieting is a perfect example of a topic that health psychologists study, because it ties something psychological (wanting to diet) with something biological (health). This kind of work is not easy, because you have to learn and master multiple fields of study, but it’s absolutely thrilling to break down traditional disciplinary boundaries to ask new questions. Why did you decide to go into teaching? Was it more difficult than you thought to become a professor? Teaching is one of the joys in my life. And to be honest, teaching a course in psychology is much easier than teaching fitness classes—something I did for close to a decade. In a fitness class, you have to do one move with the class while calling out the next one, all the while monitoring the room for correct form and safety…and while you’re out of breath. After that, sharing exciting theoretical and research findings with students felt like a breeze. As I reflect on my teaching style, I realize that I have tried to carry with me the very best qualities of many of my teachers at ASIJ: the humor of Mr Chambers and Mr O’Donnell, the passion of Mr Huber and Mr Swanson, the warmth and openness of Mr Ingebritson and Mrs Roen, the list goes on and on and on. What is it like running the DiSH (Dieting, Stress, and Health) Lab? Hectic—but a whirlwind of fun. The graduate students in my lab are spilling over with exciting, insightful research ideas, and at any given time we are simultaneously designing studies, collecting data in other studies, and writing manuscripts for still other studies. For a taste of what research has come out of the lab, check out the publications page of <www.dishlab.org.> Some of your research challenges popular “fad” diets. How can the results of such research make it out of the lab and begin to influence people’s daily lifestyle? Hopefully it will be easy, because I don’t know a single person who’s been on a fad diet and enjoyed the experience. Restrictive diets are no fun, and my research shows that they actually cause psychological stress and increases in the stress hormone cortisol (which itself promotes weight gain). My work has been covered in the popular press, which is one good way to get research out of the lab (I knew I’d made it when The Onion covered one of my dieting papers!). It’s interesting FALL 2013 the ambassador 19 features clone SCIENCE features SCIENCE Reed Hutchison/UCLA ranger Janet worked with UCLA psychology professor Dr. Traci Mann on a study analyzing 31 long-term studies of dieting – when I say diets don’t work and that they’re stressful, many people say, “Duh!” and yet many scientists find that to be shocking. That just underscores the gap between academia and the public. Japan is known for having a healthier population than many other developed countries and popular media often points to the Japanese diet as a major factor. Is there any truth in this? Yes! Japanese women in particular are the most longlived humans on earth. There is so much to praise about the (traditional) Japanese diet. Lots of vegetables and lean proteins, huge variety in the kinds of foods people eat, low fat, small portions, tons of green tea. Beyond this, however, as a psychologist I think there is something to be said about Japanese food culture. Food is an art form in Japan, and it’s something to be celebrated. I think in American culture, oftentimes food and eating are very stressful or experiences that are filled with guilt. And research shows that eating food when your body is in a state of “stress soup” leads to weight gain – in fact, it leads to the most dangerous kind of fat called visceral obesity. You’ve done a lot of groundbreaking research on stress. Have any of your discoveries changed the way that you deal with your own stress? The work that I’ve incorporated most into my daily life is actually that of my dear friend and colleague Dr Eli Puterman. He finds that exercise can buffer the negative effects of stress 20 the ambassador FALL 2013 on health. This effect appears to be very powerful—in some cases, it completely wipes out the negative effects of stress! I prioritize exercise and work out at least six times a week. What advice do you have for ASIJ students on how to maintain a healthy lifestyle? As my work with dieting and stress shows, feeling like you have to deprive yourself of something can feel terrible and that on its own can lead to maladaptive changes in your biology. I think a better approach is to think of adding things to your lifestyle. For example, eating more veggies instead of cutting out sugar. Also, it’s really important to know that you can be healthy regardless of what you weigh as long as you’re exercising and eating right and minimizing stress. Weight loss shouldn’t be the goal; becoming healthy should be. What topics are you interested in researching in the future? My new research passion is understanding weight stigma. This is an issue in both US and Japanese cultures—overweight individuals are stigmatized and treated like second-class citizens. Some of my most recent work shows that experiencing weight stigma, no matter what you actually weigh, is linked to higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol and accelerated cellular aging. That’s important, because virtually no research has linked weight stigma to a biological health outcome. Cortisol, as I mentioned, promotes weight gain, so our societal stigma might actually be a vicious cycle that causes even more weight gain, therefore more stigma, and so on. Alex Yusha ‘42, a scientist whose discoveries contributed to cancer research, on how WWII tore apart the multicultural harmony that had blossomed at ASIJ I was born in Tokyo, Japan, in 1922, and grew up there, speaking Russian and Japanese as my first languages. My father was assigned to Tokyo as the Russian attaché. He and my mother had emigrated from Russia before I was born. I did not begin to learn English until I entered the first grade at The American School in Japan. My sister, Natalya, was nine years ahead of me. She and I both attended and graduated from ASIJ, though I missed my graduation ceremony in 1942 because of the war. Among my classmates, I remember scientists such as Rudy Pariser ’41 who contributed to the research of avian disease; David Nicodemus ’33 who worked on the Manhattan Project with Oppenheimer at Los Alamos; and Albert Kobayashi ‘42 whose ceramic research was used to keep the floor of spaceships from burning. I have exchanged postcards with Amy Toda ‘40 “talk- talk- talk” who lives in Hawaii. My classmates had several nicknames for me, including “Lizard,” because I could slither to the front of the line for the slide on the playground or to get into the classroom. My mother called me “Shalun” which was Russian for prankster. My sister and I were both very shy and neither of us ever married, but I did find ways to express myself! From a photo of my school chums in the early grades (see page 22), I see Bruce Brown ’42 whose dad sold Morinaga Chocolate and Wrigley’s gum; I see Claude Raymond ‘43, a Frenchman whose dad was an architect for the Imperial Hotel; I see Charles Mitchell Jr ‘44, the son of Mr. Charles Mitchell (FF 1927-33), the principal; Jerry Downs ‘42 is there and also the pilot, William Yamamoto ‘33; also, Mrs. Persis Gladieux (FF 1930-34), Marie Louise Alonzo-Romero ’42—an Hispanic student. In my class there was a student from Ukraine; one was Jewish, Russian, and Japanese which was really hard during the war; one was British and Japanese and died in a plane crash before the war, thank goodness; and one who later jumped out of a window to his death because he couldn’t handle the chaos of war. This mix of cultures and races was all fine until the war broke out; then it was really awful. During the Occupation, I worked as an interpreter and translator (Russian, Japanese, English, and German) for what became the military hospital. As there was not much demand for my services, I began to help out in the lab. I was fortunate because I could go home at the end of the day, though it was a grueling four years for all of us. After the war, when I was about twenty-four, I traveled to the United States and immediately pursued citizenship. I remember meeting two immigration officers on the ship who would continue to pop up for visits to check up on me, always as a pair. Also, I didn’t know how to drive as it was not called for in Tokyo. So I took a driver’s education class and practiced with a friend named Hays. His wife was named Helen, but this was not the Helen Hayes—she had an ‘e’ in her name. Afterwards, with help from my father who was still in Japan, I enrolled at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon. (He and FALL 2013 the ambassador 21