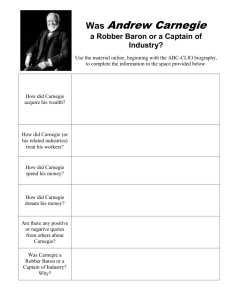

Read more about Andrew Carnegie

advertisement

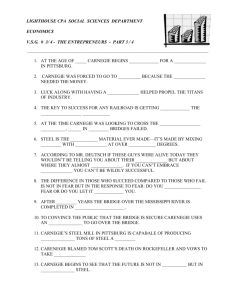

G R E AT G I V E R S Andrew Carnegie From Rags to Riches G R E AT G I V E R S Andrew Carnegie Over his 83 years of life, Andrew Carnegie created a legacy that continues to touch our lives today. He is best known for birthing the United States steel industry, which had a catalytic effect on American industrialization. This success alone would have earned Carnegie a secure place in U.S. history books, but it is what he did with his success that makes his achievements so remarkable. v Carnegie devoted the majority of his earnings to the betterment of society and did so, for the most part, during his own lifetime. v The core element of his philanthropy—the establishment of free public libraries—helped create the American library system and is one of the best-known examples of effective philanthropy. 2 Carnegie’s philanthropic instincts were at the core of his being. In his 1895 presentation of the Carnegie Library to the citizens of Pittsburgh, his address included these thoughts: Money can only be the useful drudge of things immeasurably higher than itself... My aspirations take a higher flight. Mine be it to have contributed to the enlightenment and the joys of the mind, to the things of the spirit, to all that tends to bring into the lives of REMARKABLE ACHIEVEMENTS v Carnegie devoted the majority of his earnings to the betterment of society and did so, for the most part, during his own lifetime. the toilers... sweetness and light. I hold this the noblest possible use of wealth. FROM RAGS TO RICHES Carnegie was no stranger to poverty. He was born in 1835 into a working-class family in Dunfermline, Scotland. For the first 12 years of his life, Carnegie’s four-member family lived in a one-room home. Carnegie’s father was a skilled weaver whose once-valuable skills became obsolete with the advent of the steam-powered loom, leaving the family v The core element of his philanthropy—the establishment of free public libraries—helped create the American library system and is one of the best-known examples of effective philanthropy. struggling to support itself. Eventually they borrowed money to immigrate to the United States and settled in Allegheny, Penn., where, after just five years of schooling, Carnegie immediately began his professional life. His first job was as a bobbin boy in a textile mill, but he was smart and determined to advance. He took advantage of all opportunities, made connections, chose allies wisely, took risks that others would not and had a knack for anticipating future trends. He made his way up through the railroad, telegraph and iron industries and later took aim at the steel industry. By 1900, his steel mills produced 3 more steel than Britain. By the end of his 53-year career, Carnegie was the wealthiest man in the world. INSPIRATION Carnegie’s professional life and personal life were significantly influenced by three figures who dominated his early life experiences: v His father, Will: Carnegie not only witnessed the demise of his father’s career in Scotland, but he also watched his father’s humiliation as he failed to find work in America. Carnegie once said: “It was burnt into my heart At his death, Carnegie had given away more than $350 million. When he died, his remaining $30 million was given to foundations and charities. then that my father had to beg [for work]. And then and there came the resolve that I would cure when I got to be a man.” Carnegie’s moral views were shaped by the paternal side of his family. His father and grandfather were political reformers who campaigned against the monarchy and sought to abolish a system of inherited privileges in Scotland. Through them, Carnegie was educated about the ideals of democracy and altruism. v His mother, Margaret: Carnegie was particularly close to his mother. He spent most of his life in her company and did not marry until after she died. His mother was a tough woman who instilled drive, frugality and determination in Carnegie. She motivated his ambitious climb to the top. Carnegie was acutely aware of his mother’s shame at the circumstances under which their family left Scotland. When he attained success, Carnegie fulfilled her fondest wish by taking her back to their hometown and parading her on a coach through the streets in her finery. v Colonel James Anderson: Anderson was an Allegheny, Penn., citizen who opened his home library of 400 books to local working boys. Carnegie was a voracious reader who received much of his education by reading books from this collection. On this experience, Carnegie reflected: “[A]nd it was when reveling in the treasures which he opened to us that I resolved, if ever wealth came 4 to me, that it should be used to establish free libraries, that other poor boys might receive opportunities similar to those for which we were indebted to that noble man.” ACTIONS In 1868 at age 33, Carnegie wrote a letter to himself declaring that he would only work for two more years and thereafter live on an income of $50,000 per year and devote his life to “benevolent purposes” such as philanthropy and education. Although he did not keep that vow, it hinted at his beliefs about how wealth should be allocated. Carnegie later built on the letter’s theme, publishing his treatise on philanthropy, “The Gospel of Wealth,” in 1889. In it, he articulated what he considered to be the duties of all men of wealth: v To set an example of modest, unostentatious living; v To provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; v To consider all surplus wealth as trust funds to be administered in ways that produce the most beneficial results for the community. In addition to prescribing wealthy men’s philanthropic obligation, Carnegie also opined on how and when to be philanthropic. He was a strong proponent of “giving while living” and is well-known for declaring in “The Gospel of Wealth” that “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” He viewed the wealthy as stewards of the public good and believed that one could only properly do that job if one was alive to ensure that the funds were appropriately administered to worthy causes. 5 Carnegie also clarified what he considered to be valid uses of wealth. He was particularly clear that “indiscriminate charity” is actually a detriment to society and that “the main consideration should be to help those who will help themselves…” Among the causes he considered worthy were the establishment of free libraries, public parks, art galleries, museums and concert halls; the founding and expansion of universities, medical institutions and laboratories and the support of scientific pursuits and, under specific circumstances, churches. IMPACT Carnegie’s philanthropic endeavors began in the 1870s. He donated his first free public library in 1881 to his hometown of Dunfermline. His library initiative, like many of his later philanthropic initiatives, was informed by his business acumen. He would not donate a library without sufficient community investment to ensure its sustainability. In 1901 at age 66, Carnegie sold Carnegie Steel to J.P. Morgan for $480 million. J.P. Morgan consolidated it with his companies to create U.S. Steel, and Carnegie retired from the business world, finally devoting his life to “benevolent purposes.” In the ensuing years Carnegie endowed several philanthropic institutions which still carry out their missions today including: v Carnegie Institute, a center for scientific discovery and research; v Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, a policy and research center; v Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a nonpartisan organization dedicated to advancing cooperation between nations and promoting active international engagement by the United States. Carnegie devoted himself to the many of the causes he had identified as worthy: libraries, universities, schools, churches, medical institutions and others. He built 2,509 libraries worldwide, including 1,679 libraries in 1,406 communities in the United States. He also purchased a Scottish park that he had been barred from entering as a child and gave it to the citizens of Dunfermline. In 1911, Carnegie created the Carnegie Corporation and endowed it with the majority of his remaining wealth so the corporation could continue his philanthropic initiatives after his death. When it was established, 6 the Carnegie Corporation was the largest single philanthropic trust ever created with $135 million in assets. Carnegie was the Corporation’s first president. Setting an example for future donors, Carnegie penned what is now termed a donor intent letter. His words reflected a great confidence in his trustees and placed significant responsibility on them. This portion of the letter is from the Corporation’s website: “Conditions upon erth [sic] inevitably change; hence, no wise man will bind Trustees forever to certain paths, causes or institutions. I disclaim any intention of doing so. On the contrary, I giv [sic] my Trustees full authority to change policy or causes hitherto aided, from time to time, when this, in their opinion, has become necessary or desirable. They shall best conform to my wishes by using their own judgement.” At his death, Carnegie had given away more than $350 million. When he died, his remaining $30 million was given to foundations and charities. Selected Sources “American Experience, Richest Man in the World: Andrew Carnegie Program Transcript.” PBS.org. WGBH Educational Foundation, 2009. Web. 3 June 2010. “American Experience, Richest Man in the World: Andrew Carnegie Rags to Riches Timeline.” PBS.org. WGBH Educational Foundation, 2009. Web. 3 June 2010. “Andrew Carnegie: A Tribute.” clpgh.org. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, 2010. Web. 3 June 2010. Carnegie, Andrew. “The Gospel of Wealth.” The Gospel of Wealth and and Other Timely Essays. New York: The Century Co., 1901. 1–44. Print. Carnegie Corporation site. Carnegie Corporation of New York, 2009. n.p., Web. 3 June 2010. 7