Anne Donovan

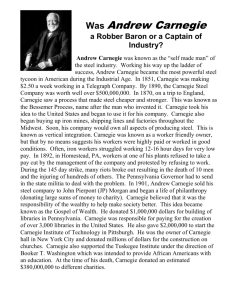

advertisement

Dear Coatbridge Library, If it weren’t for you, I would not be a reader or a writer. As a wee girl, I walked up the high steps to your imposing entrance with a sense of awe and excitement. Inside there was a parquet floor and high ceilings; this was somewhere really important. And best of all, there were rows and rows of bookshelves crammed with books. Like most folk then, we didn't have a lot of books at home. Everyone read a lot but, other than some reference books and a few special ones, books were for borrowing. I had no sense of ownership of books - the ones in the library were as much mine as any in our house. In a way that’s a healthy attitude. The only books we own are those we read and absorb into our consciousness; unread books on our walls are merely ornaments. An unread book is a sad thing; without the relationship between writer and reader it’s like an unrequited love affair. Of course I didn’t think that then - I was just overjoyed at the chance to read all those books. On Saturday mornings I got two (the maximum number for children) books out and by evening I was moaning about having nothing to read. ‘I’ve finished my books’, I’d wail, then out of necessity I re-read them, over and over again. In my experience, reading at a young age has an intensity of experience that comes less easily in adulthood. I was often so completely lost in my books that I didn’t hear someone speaking to me; the characters were more real than the so-called reality around me. Books transported me to magical places I could never have otherwise gone. I like to believe that this is still the case, even in an age when any child can travel anywhere at the touch of a screen. The interior world of the imagination, the landscapes of the mind, seem to me more powerful. In those days there were no helpful suggestions about what you might read, no ‘if you like this, you might also like that’ flowcharts, no computer-generated lists of suggestions on an Amazon site. There were just bookcases filled with books, spines turned out, neatly arranged according to the author’s surname - apart from the nonfiction books, whose mysterious codes I was not yet able to fathom. So I read everything and anything, appropriate and inappropriate, the too easy and the too difficult, the popular and the obscure. As a wee girl it was every Enid Blyton book the library possessed, alongside books about knights and castles. I was fascinated by the names of armour and learned the words for colours off by heart: gules, sable, argent. At secondary school I progressed to the adult section where I discovered the Brontes and was especially struck by the stormy passions of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. In complete contrast, PG Wodehouse was also a favourite. I also fluked upon Brave New World and subsequently read a lot of Aldous Huxley which I didn’t understand at all. I read a great many books I didn’t understand but I think there is often too much emphasis on understanding; there is a mysterious beauty about what we don’t fully grasp but can appreciate at some unconscious level, like seeing objects by the strange light that filters through trees. I also began to read all the poetry I could lay my hands on and once wrote in my diary of my dismay that I would never be able to read all the books in the library. While books were the heart of my love of the library, the building itself made the experience special. Coatbridge Library was a Carnegie Library and though this didn’t mean much to me as a child, I later found out about Andrew Carnegie, the self-made millionaire who endowed so many libraries in areas where people were not well off and wouldn’t otherwise have access to reading. I have since visited other Carnegie libraries, built around the same time at the turn of the twentieth century and they all have that grandeur, that sense of being, not just buildings which house books, but temples where something sacred is revered and protected. The building I knew and loved is no longer the library. A few years ago the council moved the library to a modern purpose-built structure which houses other local facilities and put the Carnegie library up for sale; as far as I know it still lies empty. Though I was brought up in Coatbridge I have rarely visited it since I left; I have lived all my adult life in Glasgow and consider myself a Glaswegian, so it is not my place to comment on such a decision. I sincerely hope the residents of the area enjoy their library as much as I did the old one but I feel sad at the thought of it sitting there, stripped of its books and thus of its soul. Thank you, Coatbridge Library, for awakening and nurturing my love of books. I have loved other libraries since but, like first love, you will always have a special place in my heart. Anne Donovan